Minorities, Volatile Identities and (Mis-)Identification: a Holistic Reading of HBO’S Girls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Features & Entertainment “PROMETHEUS”: TENSE

PAGE FOUR Features & Entertainment CANYON NEWS JUNE 10, 2012 “PROMETHEUS”: TENSE, THRILLING RIDE KIM FARRIS: LIVES IN WORLD OF HORRORS By LaDale Anderson By Michael St. John HOLLYWOOD—HELLO ever since I was a kid. I re - AMERICA! Very few people member hearing about the in Hollywood, especially Deer Hunter and what an pretty young actresses will impact it made in movie admit they enjoy the world history and how she was of monsters and cinematic such an amazing actress, I horror. And KIM FARRIS, is wanted to know how I can the first to say that playing be like her. a monster, is engrossing Q: Has it been difficult to and very challenging for an convince the powers-that actress. Her experience be that you are ready to working in "Walking Dead" take on bigger dramatic is actually is a learning ex - challenges if only given a perience for any actress. chance? Q: How old were you A: Oh absolutely! I'm not when you first discovered going to lie. This is one that you wanted to become tough town! I think of it an actress? What kind of more though as a challenge. motion pictures affected there are so many aspiring you, emotionally, the most? actors out there just trying Logan Marshall-Green, Noomi Rapace and Michael Fassbender in "Prometheus." A: I believe I must have to grasp that one chance. It HOLLYWOOD—There were that claustrophobic feeling. acter; she appears innocent at more so what else is out been about 8 years old when is sad the there such a small only two hotly anticipated What the movie does an ex - times, but she’s willing to go there we’re unaware of. -

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism by Rachael Horowitz Television, As a Cultural Expression, Is Uniqu

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism By Rachael Horowitz Television, as a cultural expression, is unique in that it enjoys relatively few boundaries in terms of who receives its messages. Few other art forms share television's ability to cross racial, class and cultural divisions. As an expression of social interactions and social change, social norms and social deviations, television's widespread impact on the true “general public” is unparalleled. For these reasons, the cultural power of television is undeniable. It stands as one of the few unifying experiences for Americans. John Fiske's Media Matters discusses the role of race and gender in US politics, and more specifically, how these issues are informed by the media. He writes, “Television often acts like a relay station: it rarely originates topics of public interest (though it may repress them); rather, what it does is give them high visibility, energize them, and direct or redirect their general orientation before relaying them out again into public circulation.” 1 This process occurred with the topic of feminism, and is exemplified by the most iconic females of recent television history. TV women inevitably represent a strain of diluted feminism. As with any serious subject matter packaged for mass consumption, certain shortcuts emerge that diminish and simplify the original message. In turn, what viewers do see is that much more significant. What the TV writers choose to show people undoubtedly has a significant impact on the understanding of American female identity. In Where the Girls Are , Susan Douglas emphasizes the effect popular culture has on American girls. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

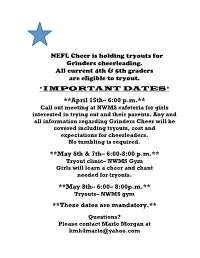

NEFL Grinders Cheer

NEFL Cheer is holding tryouts for Grinders cheerleading. All current 4th & 5th graders are eligible to tryout. *IMPORTANT DATES* **April 15th– 6:00 p.m.** Call out meeting at NWMS cafeteria for girls interested in trying out and their parents. Any and all information regarding Grinders Cheer will be covered including tryouts, cost and expectations for cheerleaders. No tumbling is required. **May 6th & 7th– 6:00-8:00 p.m.** Tryout clinic– NWMS Gym Girls will learn a cheer and chant needed for tryouts. **May 8th– 6:00– 8:00p.m.** Tryouts– NWMS gym **These dates are mandatory.** Questions? Please contact Marlo Morgan at [email protected] NEFL Grinders Cheer The tryouts for NEFL Grinders cheer will be held May 5th-7th from 6:00-8:00 in the upper gym at NWMS. The girls need to wear a t-shirt/tank, shorts, tennis shoes and have their hair pulled back. They should bring a water bottle with them. The first two nights will be the clinic where the girls will learn the cheer and chant needed for the tryouts. The third night will be the tryouts. Parents are welcome to stay in the gym and watch the clinic, but the tryouts are closed. The team will be announced that night after tryouts. All girls must be registered with NEFL before they will be allowed to tryout. You can register online at www.nefl.net. Please bring your printed receipt of registration on the first day of cheer clinic. ************************************************************************ The girls will be judged on a 1-5 scale on the following skills: -Cheer and chant memory -Motions -Voice projection -Enthusiasm -Jumps -Attitude -Tumbling will be scored as follows: -Cartwheel -1 point -Round Off - 2 points -Back Handspring - 3 points -Back Handspring series - 4 points -Tuck – 5 points The cost for participating in Grinders cheer is approximately $325-$350. -

"The Untitled Lena Dunham Project" Pilot (Together)

"THE UNTITLED LENA DUNHAM PROJECT" PILOT (TOGETHER) Written by Lena Dunham 10/23/2010 INT. MIDTOWN RESTAURANT, EVENING HANNAH-- 24, sweet-faced, slightly chubby-- sits across from her parents: TAD--early 60s, professorial-- and LOREEN, slim and understated, also in her 60s. Loreen and Tad slowly work on their food while Hannah eats speedily, back and forth between a bowl of pasta, a salad, a side of spinach and a baked potato. LOREEN Would you two slow down? You’re eating like it’s going out of style. HANNAH (mouth full) I’m a growing girl. A drip of sauce hits Tad’s shirt. TAD Meant to do that. Hannah laughs. LOREEN Your whole Brooklyn thing, Hannah. It reminds me of Berkeley in the 1970s. My boyfriend at the time, Ned. He lived in a communal space a bit like yours. HANNAH (laughing) I have one roommate, mom. LOREEN But that boyfriend of hers seems always to be around. TAD We’re sorry we never got to meet this fellow you’re dating. HANNAH Dating is probably a polite word for what we’re doing, but yeah. LOREEN Hannah, that’s your father. Spare him the TMI. (pause) That’s a thing, right? TMI? (MORE) 2. LOREEN (CONT'D) One of my students said it and I thought it was just so funny. HANNAH (to Tad) I’m sorry, papa. Did that upset you? TAD I’m rolling with it. Pause LOREEN Tad. We should probably bring it up now. TAD Let’s finish recapping the weekend and then we can-- LOREEN No, I don’t want to just leave it til the end of dinner. -

Juniors to Have Prom Girls Glee Club Pre~Ents Nnua Aster Oncert

,. SERlES V VOL. VII Stevens Point, \Vis., April 10, 1946 No. 23 College Band Again Juniors To Have Prom Girls Glee Club Pre~ents To Welcome Alums Of interest to all students is the fact that the first post-war Juni or A 1 E c The col lege band, under Ihe di rec· Promenade will be he!J as originally nnua aster oncert tion of Peter J. Michelsen, wi ll hold sc heduled on Friday, May 24. There · a h omecoming on Saturday and Sun had previously been some question day, April 27 and 28. as to whether it could be held be Holds Initiation Michelsen to Direct Approximately 36 band directors cause of the fact that the date chose n Second semester pledges became The Girls Glee club, under the plan to attend the homecoming. for the Prom was the same as that members of Sigma Tau Delta, na directi on of Peter J. Michelsen, will They wi ll play with the college selected by the freshmen for their tional honora ry English fraternity, present their fifth annual Easte r band, making a total of '65 people in proposed party. After a discussion at a meeting held last Wednesday concert on P,tlm Sunda)', April 14, the organization. between the heads of the two classes, the decision was reached to evening in Studio A. in th; coll ege aud itorium .It 3 o'clock ! he g roup will spend Saturday combine the two events in to the The new members, Joyce Kopitz in the .1fternoon. rehearsing, and on Saturday evening, Junior Prom. -

Daisy 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals! Activity

Daisy 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals! Activity Plan 1: Birdbath Award Purpose: When girls have earned this award, they will be able to say “Animals need care; I need care. I can do both.” Planning Guides Link: Leadership Activity Plan Length: 1.5 hours Resources and Tips • This activity plan has been adapted from It’s Your Story—Tell It! 5 Flowers, 4 Stories, 3 Cheers for Animals!, which can be used for additional information and activities. • Important snack note: Please check with parents and girls to see if they have any food allergies. The snack activity calls for peanut butter or a dairy product. Ask parents for alternative options that will work for the activity, if needed. Activity #1: Unique Animals Journey Connection: Session 4—Fantastical Animals Flip Book Time Allotment: 15 minutes Materials Needed: • Note cards • Coloring utensils • Tape • Paper Steps: 1. Create a list of animal body parts (head, arm, leg, ears, tail, etc.) on individual small pieces of paper. 2. Ask the girls the questions below: • What animals have you seen near where you live? • What is the most unusual animal you’ve ever seen? Where did you see it? What did it look like? 3. Split the girls into teams, hand out note cards and assign 1–2 animal body parts per girl (depending on the number of girls per group). Instruct girls not to talk to each other and to draw the body part they have on the note card for an animal, real or imaginary. 4. After girls have finished their drawings, have them work as a team to tape the different animal body parts together to create a totally unique animal friend. -

Family When Frasier Was Injured and out of Work from an Accident with a Drunk Driver in 2006 and Paid for Family Vacations Every Year

ESSAY QUESTION NO. 4 Answer this question in booklet No. 4 Margo and Frasier were married in 1997 in Anchorage. They lived there throughout the marriage. Prior to their marriage, Margo inherited her mother's farm with her siblings. From the income of the farm, Margo used $30,000 to remodel her and Frasier's marital home. The home's title is in both parties' names. The remodel significantly increased the home's value. Her farm funds also supported the family when Frasier was injured and out of work from an accident with a drunk driver in 2006 and paid for family vacations every year. In 2005, the farm was sold. Margo deposited half the money into the couple's checking account. She opened her own individual brokerage account with the remainder. Margo and Frasier separated in February 2008. They have twin daughters who are in kindergarten. In March 2008, Frasier received a bonus based on his employer's profit for 2007. Frasier's lawsuit against the drunk driver who hit him is not scheduled for trial until January 2009. Frasier has asked the court for damages including lost earnings and pain and suffering. Margo and Frasier have filed for divorce. 1. Margo has told Frasier she wants to be reimbursed all the money that she contributed to the family expenses, the home remodel and the checking account from the farm income. She also wants half the employment bonus and half the lawsuit proceeds. How would a court rule on Margo's entitlement to the farm income reimbursement, Frasier's bonus and his lawsuit monies? Discuss thoroughly. -

HBO Series Girls and Insecure's Depiction of Race and Gender

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 HBO Series Girls and Insecure’s Depiction of Race and Gender Kimberley Peterson Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Kimberley, "HBO Series Girls and Insecure’s Depiction of Race and Gender" (2018). Honors College Theses. 199. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peterson 1 HBO Series Girls and Insecure’s Depiction of Race and Gender Kimberley Peterson Peterson 2 Communication Studies Dr. Aditi Paul Communication Studies 3 May 2018 and 22 May 2018 Abstract In this research study the identification and representation of race and gender were looked at in the primetime HBO television series Insecure and Girls. The characters that were analyzed in two episodes were the young black women of Insecure and in two episodes the young white women in Girls. The method for this study was conducted using content analysis to identify the following variables focusing on identity, racial stereotypes and names used to address one another. Additionally, variables to identify gender included emotional approaches to situations, stereotypes and gender role expectations. The comprehensive findings revealed through similarities and differences of the episodes containing similar plot lines, as well as the overall analysis of each show, gave insight on how race and gender is being presented. -

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

WELCOME to V-DAY's 2003 PRESS KIT Thank You for Taking the First Step in Helping to Stop Violence Against Women and Girls

WELCOME TO V-DAY’S 2003 PRESS KIT Thank you for taking the first step in helping to stop violence against women and girls. V-Day relies on the media to help get the word out about the global reach and long-lasting effects of violence. With your assistance, we hope your audience is compelled to take action to stop the violence, rape, domestic battery, incest, female genital mutilation, sexual slavery—that many women and girls face every day around the world. Our goal is to provide media with everything you need to present the most interesting and meaningful story possible. If you require additional information or interviews, please contact Susan Celia Swan at [email protected] . In addition, you can find all of our press releases (including the most recent) posted at our site in the Press Release section. Thank you again for joining V-Day in our fight to end violence against women and girls. Susan Celia Swan Jerri Lynn Fields Media & Communications Executive Director 212-445-3288 914-835-6740 CONTENTS OF THIS KIT Page 1: Welcome To V-Day’s 2003 Press Kit Page 2: 2003 Vision Statement Page 3: 2003 Launch Press Release Page 7: About V-Day and Mission Statement Page 8: Star Support: The Vulva Choir Page 11: Quote Sheet Page 12: Biography of V-Day Founder and Artistic Director/Playwright Eve Ensler Page 13: Take Action to Stop Violence Page 14: V-Day College and Worldwide Campaigns Page 15: Selected Media Coverage Page 38: Selected Press Releases V-DAY 2003: FROM V-DAY TO V-WORLD Last year V-Day happened in 800 venues around the world.