Rethinking the Public Role of Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Conference September 10-12, 2018 • Salt Lake City

Annual Conference September 10-12, 2018 • Salt Lake City museums a catalyst belonging for Entry Douglas Ballroom Elevator Main Entry Opening Session | Keynote Session | Poster Session from Hotel parking → Meals | Breaks Sponsor Tables | Silent Auction Gender Gender Neutral Neutral Restroom Restroom Information University Guest House Meeting Rooms Alpine Concurrent Sessions Bonneville Concurrent Sessions Contents City Creek Ensign At-a-Glance Schedule ............................. 1 Key Information ....................................... 2 Concurrent Sessions Conversation Tables UMA Mission & Board ............................. 3 Explore Salt Lake City ............................ 4 Welcome Letters .................................... 5 Schedule Details ..................................... 7 Men’s Women’s Award Recipients .................................. 16 Restroom Restroom Silent Auction ....................................... 18 Museum Advocacy .............................. 19 Resources .......................................... 20 Notes Pages ......................................... 21 At-a-Glance Monday, September 10, 2018 8:00 am – 11:00 am Field Trips see page 7 11:15 am – 12:00 pm General Session CE EDOP Conference 101 Alpine 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm Break Explore local lunch spots with your colleagues local restaurants 12:00 pm – 5:30 pm Auction Silent Auction Bidding Douglas Ballroom 1:00 pm – 1:15 pm General Session Welcome Remarks Douglas Ballroom 1:15 pm – 2:15 pm Opening Session CE EDOP A Conversation About Belonging Douglas -

Art Access Utah

THURSDAY 19 MAY 2016 6-9 PM 14TH ANNUAL FUNDRAISER & EXHIBITION Art Access 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2015 - SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 Dear Friends of Art Access, Another busy year has passed and Art Access provide the perfect means for people to tell their continues to do what it does so well – connecting stories, articulate their identities, and explore their people through the storytelling inherent in the personal creativeness. We believe the arts are a creation and appreciation of art. universal vehicle for drawing out our similarities, celebrating our differences, and ultimately Art Access is creative in responding to community connecting us to each other. We are committed to needs as they are identified and in adapting telling and hearing the stories of all of us through programs to serve unique populations. Each the literary, visual, and performing arts. program is evaluated for both the financial and social return on investment. It is the social return By engaging the public in educational and artful that keeps us motivated. experiences in our galleries and in the wider community, Art Access continues to make a For example, here are a few comments we significant contribution to the cultural life of our received this year: community. “My students grew tremendously through the year All this is accomplished in partnership with by participating in these activities. I truly believe many other organizations and individuals. We they are better human beings, in touch with are fortunate to have a dedicated staff who feelings and better able to express themselves feel passionately about the Art Access mission with confidence.” – Classroom teacher and work diligently to maintain the quality and accessibility of programs. -

Salt Lake City, Utah $753,855,000 Airport Revenue Bonds, Series 2018A (AMT) $96,695,000 Airport Revenue Bonds, Series 2018B (Non-AMT)

NEW ISSUE-BOOK-ENTRY ONLY Ratings: See “RATINGS” herein. In the opinion of Kutak Rock LLP, Bond Counsel to the City, under existing laws, regulations, rulings and judicial decisions and assuming the accuracy of certain representations and continuing compliance with certain covenants, interest on the Series 2018 Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes, except for interest on any Series 2018A Bond for any period during which such Series 2018A Bond is held by a “substantial user” of the facilities financed or refinanced by the Series 2018A Bonds, or a “related person” within the meaning of Section 147(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”). Bond Counsel is further of the opinion that (a) interest on the Series 2018A Bonds constitutes an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals, and for taxable years beginning before January 1, 2018, on corporations, by the Code, and (b) interest on the Series 2018B Bonds is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax. Bond Counsel notes that no federal alternative minimum tax applies to corporations for taxable years beginning on and after January 1, 2018. Bond Counsel is further of the opinion that, under the existing laws of the State of Utah, as presently enacted and construed, interest on the Series 2018 Bonds is exempt from State of Utah individual income taxes. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. $850,550,000 SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH $753,855,000 Airport Revenue Bonds, -

Alfred Eisenstaedt About an Artist

Christian Dior (Stephen Jones), Top Hat, fall 2000. In “Paris, Capital of Fashion,” Fashion Institute of Technology, NY Fall 2019 1 ReflectingReflecting onon EqualityEquality “To start, museums should prioritize hiring curators from Inequality has run unchecked through our society, and through our museums. Are all interests of the viewing public, academic programs that invest in diversity. Donors need to more diverse than ever before, represented in the trustee’s choice support artists and academics of every background; the people of purchases? Exhibitions? Activities and programs? Is diversity entrusted with analyzing and exhibiting the American story a recognized imperative in the hiring and firing of staff? Are ought to reflect the future, or risk not being a part of it.” certain elements of the population locked out of institutions be- Things are improving: “…educational and curatorial depart- cause of the high price of admission and because of an unfamil- ments have grown more racially diverse since 2014. More than iarity with the institution’s ethos? a quarter of museum education positions are now held by people In a New York Times op-ed article by Darren Walker, president of color.” These new curators have been the creators of some of of the Ford Foundation, the subject of equality was reviewed. the most well attended and popular exhibitions. Many organi- The headline trumpeted: “Museums Need to Reflect Equality.” zations and governments that support museums are demanding evidence of the museum’s hiring practices. Many grant-making “I believe that museums have the responsibility to hold a entities also are asking proof of diversity. -

Chapter 17 University of Utah Part 1 Educational Telecommunications

Utah Code Chapter 17 University of Utah Part 1 Educational Telecommunications 53B-17-101 Legislative findings on public broadcasting and telecommunications for education. The Legislature finds and determines the following: (1) The University of Utah's Dolores Dore' Eccles Broadcast Center is the statewide public broadcasting and telecommunications facility for education in Utah. (2) The center shall provide services to citizens of the state in cooperation with higher and public education, state and local government, and private industry. (3) Distribution services provided through the center shall include KUED - TV, KUER - FM, and KUEN - TV. (4) KUED - TV and KUER - FM are licensed to the University of Utah. (5) The Utah Education and Telehealth Network's broadcast entity, KUEN - TV, is licensed to the Utah Board of Higher Education and, together with UETN, is operated on behalf of the state's systems of public and higher education. (6) All the entities referred to in Subsection (3) are under the administrative supervision of the University of Utah, subject to the authority and governance of the Utah Board of Higher Education. (7) This section neither regulates nor restricts a privately owned company in the distribution or dissemination of educational programs. Amended by Chapter 365, 2020 General Session 53B-17-101.5 Definitions. As used in this part: (1) "Board" means the Utah Education and Telehealth Network Board. (2) "Education Advisory Council" means the Utah Education Network Advisory Council created in Section 53B-17-107. (3) "Digital resource" means a digital or online library resource, including a database. (4) "Digital resource provider" means an entity that offers a digital resource to customers for license or sale. -

2 0 1 3 a N N U a L D O N O R R E P O

2013 ANNUAL DONOR REPORT Dear Friends, hank you for your commitment and generosity to the University of Utah! Your dedication and support laid the foundation for another extraordinary year at the U. With your help, the University is expanding: more students now have the opportunity to imagine and create their futures because of scholarships and Teducational opportunities provided with your assistance; learning extends beyond brick and mortar and into the local and global community; cutting-edge research continues; building renovation is under way; and new facilities with much-needed classroom, laboratory, athletic training, living, and social spaces are rising. The U is a vibrant place—and at its heart are people who share the vision of providing an exceptional educational experience that prepares students for success while enriching our community through research, artistic presentation, innovation, and publication. In 2005, The University of Utah extended an invitation to our friends to join us as partners in shaping the future of the U. Together We Reach: The Campaign for the University of Utah began. Together, we celebrate the incredible progress made since then, but there is still much we can do—together. Your generosity during the past year was remarkable and made FY 2012 the high watermark for private support at the U. I invite your continued support of the state’s flagship institution and recognize, with sincere gratitude, what your contributions have created. Many thanks, David W. Pershing President, The University of Utah 3 THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH together we reach the Campaign for the University of Utah 4 University of Utah I 2013 Annual Donor Report Progress to Date June 1, 2005 – June 30, 2013 Scholarships & Fellowships: . -

2007 Annual Utah Division of Arts & Museums Report

2007 ANNUAL Utah Division of Arts & Museums REPORT Utah Division of Arts and Musueums • 617 East South Temple, Salt Lake City, Utah 84102 Phone 801 236 7555 • Fax 801 236 7556 • artsandmuseums.utah.gov Jon M. Huntsman, Jr. tabLE oF ConTEnTS MESSAgE FroM ThE govErnor, state oF utah Utah’s astonishing beauty serves as a palate of inspiration for the arts. For the Anasazi and Fremont, the walls of red rock that surrounded them provided a Message from the Governor 1 canvas for their expression of life and culture in petroglyphs and pictographs. From the rudimentary need Message from the Chair, Board of Directors, Utah Arts Council 2 For the artists who followed these ancient artisans, the grandeur of the mountains, lakes, rivers, and unrivaled desert beauty has elevated their creative expressions Message from the Executive Director, Utah Arts Council 3 for relief from the harsh of art in all forms. In turn, the artists have helped elevate the quality of life for the people of the great state of Utah. Message from the Chair, Board of Directors, Utah Office of Museum Services 4 and tedious life of The evolution of the arts in Utah has been significant and dramatic. From the Message from the Director, Utah Office of Museum Services 5 early settlers to the need for rudimentary need for relief from the harsh and tedious life of early settlers to the need for a refreshing interlude from the stress and noise of modern life, art has Advancing the Arts 6 a refreshing interlude from the served as the source for uplifting serenity and introspection. -

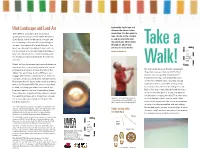

Finch Walking Guide Pdf.Indd

Explore the landscape and Utah Landscape and Land Art discover the vibrant colors The UMFA is situated in the unique and around you. Use this guide to spectacular landscape of the North American look closely and be creative Great Basin. From the Museum, you can see as you uncover color and the snowcapped Wasatch Mountain Range to document your observations the east, the Oquirrh Mountain Range to the through art. Share your Take a west, and the Salt Lake Valley to the south. To journey on social media. the northwest, you can see Great Salt Lake—a #umfawalkabout ✂ remnant of prehistoric Lake Bonneville—and CUT the arid desert, beyond which lie the ethereal ALONG DOTTED salt flats. LINE Utah’s striking landscape has inspired artists for Walk! centuries, from the ancient people who carved Be inspired by Spencer Finch’s installation petroglyphs in rock to the Land artists of the Great Salt Lake and Vicinity (2017), Finch 1960s, 70s, and today. At the UMFA you can engage with objects and interpretive materials created this site-specific installation of that will connect you with great earthworks like Pantone color chips in the Utah Museum Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Nancy of Fine Arts (UMFA) after a journey around Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973–76), both located here Great Salt Lake in June 2017 during which in Utah, and help you better understand our he recorded the colors of the things he saw. human impact on the land. Learn about these Each color chip is hand-labeled with the name fascinating and important Utah artworks, watch of its source—the bark of a tree, the water in for upcoming meet-ups at these sites, and get the distance, the wing of a bird. -

Printmaking Through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012

Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Printmaking as Art 6 Glossary of Printing Terms 7 A Brief History of Printmaking Written by Jennifer Jensen 10 Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap , Rembrandt Written by Hailey Leek 11 Lesson Plan for Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap Written by Virginia Catherall 14 Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo, Hokusai Written by Jennifer Jensen 16 Lesson Plan for Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo Written by Jennifer Jensen 20 Lambing , Leighton Written by Kathryn Dennett 21 Lesson Plan for Lambing Written by Kathryn Dennett 32 Madame Louison, Rouault Written by Tiya Karaus 35 Lesson Plan for Madame Louison Written by Tiya Karaus 41 Prodigal Son , Benton Written by Joanna Walden 42 Lesson Plan for Prodigal Son Written by Joanna Walden 47 Flotsam, Gottlieb Written by Joanna Walden 48 Lesson Plan for Flotsam Written by Joanna Walden 55 Fourth of July Still Life, Flack Written by Susan Price 57 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 59 Reverberations, Katz Written by Jennie LaFortune 60 Lesson Plan for Reverberations Written by Jennie LaFortune Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership and the Professional Outreach Programs in the Schools (POPS) through the Utah State Office of Education 1 Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Image List 1. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume , 1638 Etching Gift of Merrilee and Howard Douglas Clark 1996.47.1 2. -

PRESENTING SPONSOR $35,000 Mark & Kathie Miller Foundation

UD RO T P O Thank you to our 2011 Network of Friends. We could not do this without our generous sponsors, in-kind donors and other supporters. S T Thanks for making a difference! U P P O R PRESENTING SPONSOR $35,000 Mark & Kathie Miller Foundation GOLD SPONSORS Henriksen/Butler Workers Compensation Fund SILVER SPONSOR Layton Construction BRONZE SPONSORS ARUP Laboratories Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Utah Cerner Rumor Advertising Epic Semnani Family Foundation Ernst & Young Silverado Senior Living FFKR Architects Vehix Love Communications Wells Fargo Moreton & Company Zions Bank ADDITIONAL SUPPORT PROVIDED BY Clinical Neurosciences Nutrition Care Services Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology University Neuropsychiatric Institute Department of Orthopaedics University of Utah Health Care Department of Pediatrics University of Utah Hospitals & Clinics Department of Psychiatry IN-KIND DONORS 9th South Delicatessen Clark Executive Detail A Dance Scene Howard Clark Denise Achelis Clark Planetarium Adib’s Rug Gallery Community Clinics Admin Office Alta Ski Lifts Company Continuing Education/ Lifelong Learning American Laser Centers Corner Bakery Cafe Anonymous Crystal Inn Aristo’s Desert Star Playhouse Asart Design Diamond Rental Asian Star Dillards Anne Asman Discovery Gateway Ballet West Disneyland Resort Bambara Douglas Kondo Banbury Cross Dr. Michael Lowry Barry Ryskamp Lanette Dunbar Beans & Brews Eggs in the City Best Western Zion Park Inn EleTent Big Apple Pizza Este Pizzeria Bikram Yoga College of India Express Recovery Services Bill Child Fat Cats The Book Fair LLC Feature Films For Families Boondocks Fun Center Sherry & Cary Fife Brickyard Animal Hospital Finn’s Cafe Brighton Ski Resort Flight Clothing Boutique Bringhurst Process Service George S. -

Issuance of Series 2021 Bonds for Financing the Construction of The

ERIN MENDENHALL OFFICE OF THE MAYOR Mayor CITY COUNCIL TRANSMITTAL Lisa______________________________ Shaffer (May 11, 2021 17:32 MDT) Date Received: May 11, 2021 Lisa Shaffer, Chief Administrative Officer Date Sent to Council: May 11, 2021 TO: Salt Lake City Council DATE: May 11, 2021 Amy Fowler, Chair Bill Wyatt (May 11, 2021 10:47 MDT) FROM: Bill Wyatt, Salt Lake City Department of Airports, Executive Director SUBJECT: Issuance of Series 2021 Bonds (the “Bonds”) for Financing the Construction of the New SLC International Airport STAFF CONTACTS: Bill Wyatt, Executive Director, 801-575-2408 Brian Butler, Airport Chief Financial Officer, 801-575-2923 DOCUMENT TYPE: Resolution RECOMMENDATION: That the City Council adopt a resolution (the “Bond Resolution”) on June 1, 2021, authorizing and/or approving: (1) the issuance and sale of up to $1,000,000,000 principal amount of Salt Lake City, Airport Revenue Bonds, Series 2021A and Series 2021B (collectively the “2021 Bonds”), and the giving of authority to certain officers to approve the final terms and provisions of and confirm the issuance of the 2021 Bonds within certain parameters set forth in the attached Bond Resolution; (2) certain documents to be entered into by the City in connection with the issuance of the 2021 Bonds or to be used in the marketing of the 2021 Bonds, (3) holding a public hearing on July 13, 2021, with respect to the issuance of the 2021 Bonds and the continued borrowing under the JPMorgan Chase line of credit at tax-exempt rates, and (4) certain other related matters associated with the issuance of the 2021 Bonds. -

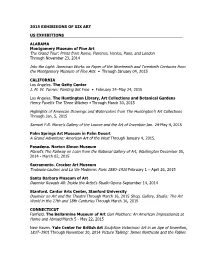

2015 Exhibitions of XIX ART

2015 EXHIBItiONS OF XIX ART US EXHIBITIONS ALABAMA Montgomery Museum of Fine Art The Grand Tour: Prints from Rome, Florence, Venice, Paris, and London Through November 23, 2014 Into the Light: American Works on Paper of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts • Through January 04, 2015 CALIFORNIA Los Angeles. The Getty Center J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free • February 24–May 24, 2015 Los Angeles. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens Henry Fuseli’s The Three Witches • Through March 30, 2015 Highlights of American Drawings and Watercolors from The Huntington’s Art Collections Through Jan. 5, 2015 Samuel F.B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention Jan. 24-May 4, 2015 Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Desert A Grand Adventure: American Art of the West Through January 4, 2015. Pasadena. Norton Simon Museum Manet's The Railway on Loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington December 05, 2014 - March 02, 2015 Sacramento. Crocker Art Museum Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880–1910 February 1 – April 26, 2015 Santa Barbara Museum of Art Daumier Reveals All: Inside the Artist’s Studio Opens September 14, 2014 Stanford. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University Daumier on Art and the Theatre Through March 16, 2015 Shop, Gallery, Studio: The Art World in the 17th and 18th Centuries Through March 16, 2015 CONNECTICUT Fairfield. The Bellarmine Museum of Art Gari Melchers: An American Impressionist at Home and Abroad March 5 - May 22, 2015 New Haven. Yale Center for British Art Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Through November 30, 2014 Picture Talking: James Northcote and the Fables Through December 14, 2014 Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain Through December 14, 2014 DELAWARE Delaware Art Museum Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: Illustrating Death and Desire • February 7, 2015 - May 10, 2015 FLORIDA Gainesville.