Increasing Egg Consumption at Breakfast Is Associated With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty, Charity and the Papacy in The

TRICLINIUM PAUPERUM: POVERTY, CHARITY AND THE PAPACY IN THE TIME OF GREGORY THE GREAT AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTEENTH DAY OF MARCH, 2013 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ___________________________ Miles Doleac APPROVED: ________________________ Dennis P. Kehoe, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ F. Thomas Luongo, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ Thomas D. Frazel, Ph.D AN ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of Gregory I (r. 590-604 CE) in developing permanent ecclesiastical institutions under the authority of the Bishop of Rome to feed and serve the poor and the socio-political world in which he did so. Gregory’s work was part culmination of pre-existing practice, part innovation. I contend that Gregory transformed fading, ancient institutions and ideas—the Imperial annona, the monastic soup kitchen-hospice or xenodochium, Christianity’s “collection for the saints,” Christian caritas more generally and Greco-Roman euergetism—into something distinctly ecclesiastical, indeed “papal.” Although Gregory has long been closely associated with charity, few have attempted to unpack in any systematic way what Gregorian charity might have looked like in practical application and what impact it had on the Roman Church and the Roman people. I believe that we can see the contours of Gregory’s initiatives at work and, at least, the faint framework of an organized system of ecclesiastical charity that would emerge in clearer relief in the eighth and ninth centuries under Hadrian I (r. 772-795) and Leo III (r. -

Rank Orders of Mammalian Pathogenicity-Related PB2

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Rank orders of mammalian pathogenicity-related PB2 mutations of avian infuenza A viruses Chung-Young Lee1, Se-Hee An1, Jun-Gu Choi 4, Youn-Jeong Lee4, Jae-Hong Kim1,3 & Hyuk-Joon Kwon2,3,5* The PB2 gene is one of the key determinants for the mammalian adaptation of avian infuenza A viruses (IAVs). Although mammalian pathogenicity-related mutations (MPMs) in PB2 genes were identifed in diferent genetic backgrounds of avian IAVs, the relative efects of single or multiple mutations on viral ftness could not be directly compared. Furthermore, their mutational steps during mammalian adaptation had been unclear. In this study, we collectively compared the efects of individual and combined MPMs on viral ftness and determined their rank orders using a prototypic PB2 gene. Early acquired mutations may determine the function and potency of subsequent mutations and be important for recruiting multiple, competent combinations of MPMs. Higher mammalian pathogenicity was acquired with the greater accumulation of MPMs. Thus, the rank orders and the prototypic PB2 gene may be useful for predicting the present and future risks of PB2 genes of avian and mammalian IAVs. Waterfowl are reservoirs for infuenza A viruses (IAVs), and close interaction between waterfowl and other ani- mals causes occasional cross species transmission to result in successful settle-down by acquiring host adaptive mutations in their eight segmented genomes (PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M, and NS)1. In particular, the PB2 protein, which is involved in cap snatching of the host mRNA, has been regarded as one of the key molecules to overcome species-specifc host barriers2–4. -

A Complete Course

A Complete Course Forum Theological Midwest Author: Rev.© Peter V. Armenio Publisher:www.theologicalforum.org Rev. James Socias Copyright MIDWEST THEOLOGICAL FORUM Downers Grove, Illinois iii CONTENTS xiv Abbreviations Used for 43 Sidebar: The Sanhedrin the Books of the Bible 44 St. Paul xiv Abbreviations Used for 44 The Conversion of St. Paul Documents of the Magisterium 46 An Interlude—the Conversion of Cornelius and the Commencement of the Mission xv Foreword by Francis Cardinal George, to the Gentiles Archbishop of Chicago 47 St. Paul, “Apostle of the Gentiles” xvi Introduction 48 Sidebar and Maps: The Travels of St. Paul 50 The Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 49– 50) 1 Background to Church History: 51 Missionary Activities of the Apostles The Roman World 54 Sidebar: Magicians and Imposter Apostles 3 Part I: The Hellenistic Worldview 54 Conclusion 4 Map: Alexander’s Empire 55 Study Guide 5 Part II: The Romans 6 Map: The Roman Empire 59 Chapter 2: The Early Christians 8 Roman Expansion and the Rise of the Empire 62 Part I: Beliefs and Practices: The Spiritual 9 Sidebar: Spartacus, Leader of a Slave Revolt Life of the Early Christians 10 The Roman Empire: The Reign of Augustus 63 Baptism 11 Sidebar: All Roads Lead to Rome 65 Agape and the Eucharist 12 Cultural Impact of the Romans 66 Churches 13 Religion in the Roman Republic and 67 Sidebar: The Catacombs Roman Empire 68 Maps: The Early Growth of Christianity 14 Foreign Cults 70 Holy Days 15 Stoicism 70 Sidebar: Christian Symbols 15 Economic and Social Stratification of 71 The Papacy Roman -

Western Europe After the Fall of Rome

1/17/2012 Effects of Germanic Invasions End of the 5th Century Raiders, • Repeated invasions, constant warfare Traders and – Disruption of trade • Merchants invaded from land and sea— Crusaders: businesses collapse – Downfall of cities Western Europe • Cities abandoned as centers for administration After the Fall of – Population shifts • Nobles and other city-dwellers retreat to rural Rome areas • Population of Western Europe became mostly rural The Rise of Europe 500-1300 The Early Middle Ages • Europe was cut off from the advanced civilizations of Byzantium, the Middle East, China and India. • Between 700 and 1000, Europe was battered by invaders. • New forms of social organization developed amid the fragmentation • Slowly a new civilization would emerge that blended Greco-Roman, Germanic and Christian traditions. akupara.deviantart.com Guiding Questions Decline of Learning 1.How was Christianity a unifying social and • Germanic invaders could not read or write political factor in medieval Europe? – Oral tradition of songs and legends • Literacy dropped among those moved to rural areas 2.What are the characteristics of Roman • Priests and other church officials were among Catholicism? the few who were literate • Greek Knowledge was almost lost – Few people could read Greek works of literature, science, and philosophy 1 1/17/2012 Loss of Common Language A European Empire Evolves • Latin changes as German-speaking • After the Roman Empire, Europe divided into people mix with Romans 7 small kingdoms (some as small as Conn.) • No longer understood from region to • The Christian king Clovis ruled the Franks region (formerly Gual) • By 800s, French, Spanish, and other • When he died in 511, the kingdom covered Roman-based (Romance) languages much of what is now France. -

University of Birmingham Algerian Women and the Traumatic

University of Birmingham Algerian Women and the Traumatic Decade: Daoudi, Anissa License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Daoudi, A 2017, 'Algerian Women and the Traumatic Decade: Literary Interventions', Journal of Literature and Trauma Studies. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. If you believe that this is the case for this document, please contact [email protected] providing details and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate. -

How Access to Plant & Animal Books Affects Participation in Conservation Activities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Summer 5-26-2015 How Access to Plant & Animal Books Affects Participation in Conservation Activities Dustin Ingram Miami University, [email protected] Hassnaa Ingram Miami University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Zoology Commons Ingram, Dustin and Ingram, Hassnaa, "How Access to Plant & Animal Books Affects Participation in Conservation Activities" (2015). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1261. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1261 Running Head: ACCESS TO BOOKS AFFECTS CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 1 How Access to Plant & Animal Books Affects Participation in Conservation Activities Dustin Ingram (Corresponding Author) Email: [email protected] Hassnaa Ingram Email: [email protected] Miami University Project Dragonfly 501 East High Street Oxford, OH 45056 ACCESS TO BOOKS AFFECTS CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 2 Abstract Public libraries are an important resource for communities. Access to plant and animal books impacts a communities’ ability to learn about their environment. In this study, the number of plant and animal books available to people through local libraries in northern Kentucky, and neighboring counties in Ohio and Indiana were counted and a survey assessing one’s preferences and likeliness to participate in conservation activities was distributed to local residents. Based on the collected data, a statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05) was found between access to plant and animal books available at local libraries and the likelihood of people to participate in conservation activities. -

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages After the collapse of Rome, Western Europe entered a period of political, social, and economic decline. From about 500 to 1000, invaders swept across the region, trade declined, towns emptied, and classical learning halted. For those reasons, this period in Europe is sometimes called the “Dark Ages.” However, Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions eventually blended, creating the medieval civilization. This period between ancient times and modern times – from about 500 to 1500 – is called the Middle Ages. The Frankish Kingdom The Germanic tribes that conquered parts of the Roman Empire included the Goths, Vandals, Saxons, and Franks. In 486, Clovis, king of the Franks, conquered the former Roman province of Gaul, which later became France. He ruled his land according to Frankish custom, but also preserved much of the Roman legacy by converting to Christianity. In the 600s, Islamic armies swept across North Africa and into Spain, threatening the Frankish kingdom and Christianity. At the battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel led the Frankish army in a victory over Muslim forces, stopping them from invading France and pushing farther into Europe. This victory marked Spain as the furthest extent of Muslim civilization and strengthened the Frankish kingdom. Charlemagne After Charlemagne died in 814, his heirs battled for control of the In 786, the grandson of Charles Martel became king of the Franks. He briefly united Western empire, finally dividing it into Europe when he built an empire reaching across what is now France, Germany, and part of three regions with the Treaty of Italy. -

TS-590S Family: Hints and Tips Archive Updated 24 November 2014 1

TS-590S Family: Hints and Tips Archive Updated 24 November 2014 1 TS-590S FAMILY: Hints and Tips Archive From time to time the TS-590S Resources Page ( http://homepage.ntlworld.com/wadei/ts-590s.htm ) carries an addition to the “Hint and Tips” section. This document is an archive of those hints. If you would like to add a Hint/Tip to the Resources Page, please email the details to Ian Wade, G3NRW ( [email protected] ). Hint Date Title Page #1 20 June 2012 Eliminating contact bounce on a straight key 3 #2 28 June 2012 Setting up the Speech Processor 3 #3 4 July 2012 Transmitting Automatically with the VGS-1 Speech Module 4 #4 12 July 2012 Breakout Box for the ACC2 Connector 4 #5 18 July 2012 Turning the TS-590S “ON” and “OFF” 5 #6 24 July 2012 Virtual COM Port Drivers 5 #7 1 August 2012 A Little Soft Compression can do a lot of Good 6 #8 8 August 2012 N1MM Logging Software uses VFO-A 6 #9 15 August 2012 The Most Basic Pieces of Test Equipment 7 #10 18 August 2012 Audio Tailoring Really Works 8 #11 27 August 2012 ARCP-590 Frequency Readout Display Cut-Off 9 #12 4 September 2012 Receive Audio Profiles 10 #13 11 September 2012 FM Audio TX Profile 11 #14 25 September 2012 Adjusting the Output Power Meter Reading 11 #15 5 October 2012 Replacing the F901 Fuse 12 #16 15 October 2012 TS-590S Noise Reduction Suggestions 12 #17 23 October 2012 Removing the Power Connector 13 #18 4 November 2012 Command-Line or Shortcut Access to Windows Audio Mixers 13 #19 18 November 2012 Ham Radio Deluxe and TS-590S TX Control 14 #20 25 November 2012 Considering -

Unit 5: the Post-Classical Period: the First Global Civilizations

Unit 5: The Post-Classical Period: The First Global Civilizations Name: ________________________________________ Teacher: _____________________________ IB/AP World History 9 Commack High School Please Note: You are responsible for all information in this packet, supplemental handouts provided in class as well as your homework, class webpage and class discussions. What do we know about Muhammad and early Muslims? How do we know what we know? How is our knowledge limited? Objective: Evaluate the primary sources that historians use to learn about early Muslims. Directions: Below, write down two things you know about Muhammad and how you know these things. What I know about Muhammad... How do I know this …. / Where did this information come from... Directions: Below, write down two things you know about Muslims and how you know these things. What I know about Muslims... How do I know this …. / Where did this information from from... ARAB EXPANSION AND THE ISLAMIC WORLD, A.D. 570-800 1. MAKING THE MAP 1. Locate and label: 4. Locate and label: a Mediterranean Sea a Arabian Peninsula b Atlantic Ocean b Egypt c Black Sea c Persia (Iran) d Arabian Sea d Anatolia e Caspian Sea e Afghanistan f Aral Sea f Baluchistan g Red Sea g Iraq h Persian Gulf. 2. Locate and label: h Syria a Indus River i Spain. b Danube River 5. Locate and label: c Tigris River a Crete b Sicily d Euphrates River c Cyprus e Nile River d Strait of Gibraltar f Loire River. e Bosphorus. 3. Locate and label: 6. Locate with a black dot and a Zagros Mountains label: b Atlas Mountains a Mecca c Pyrenees Mountains b Medina d Caucasus Mountains c Constantinople e Sahara Desert. -

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

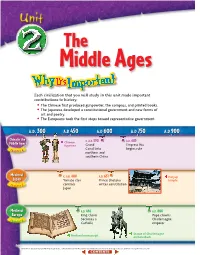

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

Your Name Your

Vedran Bileta ON THE FRINGES OF THE SHRINKING EMPIRE THE MILITARIZATION OF ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY IN BYZANTINE HISTRIA MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2010 i CEU eTD Collection ii ON THE FRINGES OF THE SHRINKING EMPIRE THE MILITARIZATION OF ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY IN BYZANTINE HISTRIA by Vedran Bileta (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ iii Examiner Budapest May 2010 CEU eTD Collection iv ON THE FRINGES OF THE SHRINKING EMPIRE THE MILITARIZATION OF ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY IN BYZANTINE HISTRIA by Vedran Bileta (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2010 v ON THE FRINGES OF THE SHRINKING EMPIRE THE MILITARIZATION OF ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY IN BYZANTINE HISTRIA by Vedran Bileta (Croatia) Thesis submitted to -

General Instructions Income Tax

GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS INCOME TAX INTRODUCTION must be the same as the Federal. A copy of the Federal return The Georgia law recognizes an election to file as an S Corpo- and all supporting schedules must be attached to the Georgia ration under the provisions of the IRC as it existed on January return. If a Federal audit results in a change in taxable income, 1, 2002, qualified only in cases of nonresident shareholders, the taxpayer shall make a return to the Commissioner of the who must complete Form 600 S-CA (see Page 9). It also pro- changed or corrected net income within 180 days of final deter- vides for the imposition of a Net Worth Tax. mination. The return should be mailed to: Georgia Income Tax Division, P.O. Box 49432, Atlanta, Georgia 30359-1432. FILING REQUIREMENTS COMPUTING GEORGIA TAXABLE INCOME All corporations owning property or doing business within SCHEDULE 1 Georgia are required to file a Georgia income tax return. (Please If an S Corporation is required to pay a tax at the federal level, round all dollar entries.) A corporation electing the provisions of it may be required to pay a tax at the state level. This schedule the IRC for S Corporations, having one or more stockholders applies only to S Corporations which have converted from a C who are nonresidents of Georgia, must file a Form 600 S-CA Corporation and are subject to the corporate income tax due to on behalf of each nonresident. Failure to furnish a properly Excess Net Passive Investment Income, Capital Gains or Built executed Form 600 S-CA for each nonresident stockholder in Capital Gains.