Dick Singer, Tales of a Wireless Pioneer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covertactloii Informmon BULLETIN R ^

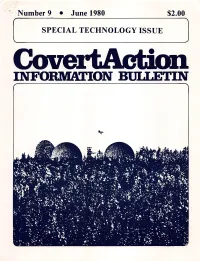

Number 9 • June 1980 $2.00 SPECIAL TECHNOLOGY ISSUE ^ CovertActloii INFORMmON BULLETIN r ^ V Editorial Last issue we noted that no CIA charter at all would be Overplaying Its Hand better than the one then working its way through Congress. It now seems that pressures from the right and left and the Perhaps the CIA overplayed its hand. Bolstered by complexities of election year politics in the United States events in Iran and Afghanistan the Agency was not content have all combined to achieve this result. to accept a "mixed" charter. By the beginning of 1980 journalists were convinced that no restrictions would pass. Stalling and Dealing Accountability, suggested Los Angeles Times writer Robert Toth, would remain minimal and uncodified, and At the time of the Church Committee Report in 1976, "Congress, responding to the crisis atmosphere during a there were calls for massive intelligence reforms and ser short election-year session, will set aside the complex legal ious restrictions on the CIA. By a sophisticated mixture of issues in the proposed charter while ending key restraints stalling, stonewalling, and deal-making, the CIA and its on the CIA and other intelligence agencies." It now seems supporters managed, in three years, to reverse the trend that Toth was 100% wrong. completely. There were demands to "unleash" the CIA. A first draft charter proposed some new restrictions and re laxed some existing ones. The Administration, guided by The Disappearing Moral Issue the CIA, attacked all the restrictions. The Attorney Gener al criticized "unnecessary restrictions," and hoped that The major public debate involved prior notice. -

Hughes Glomar Explorer a Mark of World-Class Engineering History

D EPARTMENTS D RILLING AHEAD Hughes Glomar Explorer a mark of world-class engineering history Linda Hsieh, Associate Editor the “claw” and load during the transition from dynamic open water conditions to THIRTY-FIVE YEARS ago, at the height the shelter of the ship’s center well. of the Cold War, the US government drew a plan to retrieve part of a sunken Soviet A COVERT MISSION submarine from the Pacific Ocean. And to realize that plan, the government To hide the ship’s real mission, a story turned to the drilling industry. was concocted that billionaire Howard Hughes built it for deep sea mining. It Specifically, the Central Intelligence was a great cover-up, Mr Crooke said. Agency turned to Global Marine in “Who knew what a mining ship really Houston. CIA agents showed up at the looked like? It could look like whatever company in November 1969 and asked we wanted it to look like!” it to do what, at the time, seemed an impossible task: lift a 2,000-ton asym- T he Explorer was completed in July 1973 metrical object from about 17,000 ft of at a cost of more than $200 million, and water. the salvage mission commenced a year later in July 1974, taking just 5 weeks to But Curtis Crooke, then Global Marine’s complete . vice president of engineering , believed the task was possible, and so the com- In 1996, Global Marine leased the ves- pany was recruited into a government sel and converted it into a deepwater “black” program – completely classified drillship. -

A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack Mcguinn, Senior Editor

addendum A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack McGuinn, Senior Editor In the summer of 1974, long before Argo, there was “AZORIAN” — the code name for a CIA gambit to recover cargo entombed in a sunk- en Soviet submarine — the K-129 — from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. The challenge: exhume — intact — a 2,000-ton submarine and its suspicious cargo from 17,000 feet of water. HowardUndated Robard Hughes Jr. photo of a young Howard Hughes — The Soviet sub had met its end (no one ($3.7 billion in 2013 dollars),” but none entrepreneur, inventor, movie producer — whose claims to know how, and the Russians of it came out of Hughes’ pocket. Jimmy Stewart-like weren’t talking) in 1968, all hands lost, Designated by ASME in 2006 as “a appearance here belies some 1,560 nautical miles northwest of historical mechanical engineering land- the truly bizarre enigma he would later become. Hawaii. After a Soviet-led, unsuccessful mark,” the ship had an array of mechani- search for the K-129, the U.S. undertook cal and electromechanical systems with one of its own and, by the use of gath- heavy-duty applications requiring robust But now, the bad news: After a num- ered sophisticated acoustic data, located gear boxes; gear drives; linear motion ber of attempts, the ship’s “custom claw” the vessel. rack-and-pinion systems; and precision managed to sustain a firm grip on the What made this noteworthy was that teleprint (planetary, sun, open) gears. submarine, but at about 9,000 feet the U-boat was armed with nuclear mis- One standout was the Glomar’s roughly two-thirds of the (forward) hull siles. -

Deep Sea Drilling Project Initial Reports Volume 49

Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project A Project Planned by and Carried Out With the Advice of the JOINT OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTIONS FOR DEEP EARTH SAMPLING (JOIDES) Volume XLIX covering Leg 49 of the cruises of the Drilling Vessel Glomar Challenger Aberdeen, Scotland to Funchal, Madeira July—September 1976 PARTICIPATING SCIENTISTS Bruce P. Luyendyk, Joe R. Cann, Wendell A. Duffield, Angela M. Faller, Kazuo Kobayashi, Richard Z. Poore, William P. Roberts, George Sharman, Alexander N. Shor, Maureen Steiner, John C. Steinmetz, Jacques Varet, Walter Vennum, David A. Wood, and Boris P. Zolotarev SHIPBOARD SCIENCE REPRESENTATIVE George Sharman POST-CRUISE SCIENCE REPRESENTATIVE Stan M. White SCIENCE EDITOR James D. Shambach Prepared for the NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION National Ocean Sediment Coring Program Under Contract C-482 By the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Scripps Institution of Oceanography Prime Contractor for the Project This material is based upon research supported by the National Science Foundation under Contract No. C-482. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations ex- pressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. References to this Volume: It is recommended that reference to whole or part of this volume be made in one of the following forms, as appropriate: Luyendyk, B. P., Cann, J. R., et al., 1978. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, v. 49: Washington (U.S. Government Printing Office). Mattinson, J. M., 1978. Lead isotope studies of basalts from IPOD Leg 49, In Luyendyk, B. P., Cann, J. R., et al., 1978. -

FY 2004 Budget Request Summary

TABLE OF CONTENTS Bureau Overview..............................................................................................1 Organizational Chart ...........................................................................................2 MMS Assessment Management Process ............................................................3 Fiscal and Energy Benefits of MMS Activities .................................................5 What Does the Future Hold? ...........................................................................7 FY 2004 Budget Request Summary ...................................................................8 Maintaining Operations ......................................................................................9 Visionary Requirement .....................................................................................10 Increased Security ............................................................................................11 Total FY 204 Funding for MMS Operations.....................................................11 Making Improvements ......................................................................................12 President’s Management Agenda .....................................................................13 Contributions to DOI Draft Strategic Plan .......................................................16 Budget Allocation Table ..................................................................................17 Budget Estimate.......................................................................... -

Shipbreaking" # 41

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 41, from July 1 to September 30, 2015 Content Offshore platforms: radioactive alert 1 Pipe layer 21 Reefer 37 Waiting for the blowtorches 3 Offshore supply vessel 22 Bulk carrier 38 Military & auxiliary vessels 7 Tanker 24 Cement carrier 47 The podium of best ports 13 Chemical tanker 26 Car carrier 47 3rd quarter overview: the plunge 14 Gas tanker 27 Ferry 48 Letters to the Editor 16 General cargo 28 Passenger ship 56 Seismic research 17 Container ship 34 Dredger 57 Drilling 18 Ro Ro 36 The End: Sitala, 54 years later 58 Drilling/FPSO 20 Tuna seiner / Factory ship 37 Sources 60 Offshore platforms: radioactive alert The arrival of « Nobi », St. Kitts & Nevis flag, in Bangladesh. © Birat Bhattacharjee Many offshore platforms built in the 1970s-1980’s have been sent to the breaking yards by the long- lasting drop in oil prices and the low profile of offshore activities. Owners gain an ultimate profit from dismantlement. Most of the offshore platforms sent to be demolished since the beginning of the year are semi-submersible rigs. This type of rig weighs 10 to 15,000 t, i.e. a gain for the last owners of 2-4 million $ on the current purchase price from shipbreaking yards. Seen in the scrapyards: Bangladesh: DB 101, Saint-Kitts-and-Nevis flag, 35.000 t. Nobi, Saint-Kitts-and-Nevis flag, 14.987 t. India: Ocean Epoch, Marshall Islands flag, 11.099 t. Octopus, 10.625 t. Turkey: Atwood Hunter, Marshall Islands flag. GSF Arctic I, Vanuatu flag. -

National Reconnaissance: Journal of the Discipline and Practice, 2005-C1, Pp

UNCLASSIFIED NATI!ONAL RECONNAISSANCE JOURNAL OF THE DISCIPLINE AND PRACTlCt: 2005-U1 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF NATIONAL RECONNAISSANCE UNCLASSIFIED NATIONAL UNCLASSIFIED RECONNAISSANCE Editorial Staff EDITOR Robert A. McDonald ASSISTANT EDITOR Patrick D. Widlake PUBLICATION COORDINATOR Kimberly G. Hall EDITORIAL SUPPORT Sharon Moreno William M. Naylor Frances Lawson DESIGN AND LAYOUT Media Services Center Director of Policy Michael E. Brennan The Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance (CSNR) publishes National Reconnaissance for the educa tion and information of the national reconnaissance community. National Reconnaissance facilitates a synthesis of the technical, operational, and policy components that define and shape the enterprise of national reconnaissance. Employees and alumni of the National Reconnaissance Office, and its mission and industry partners, may submit items to be considered for publication. The Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance (CSNR) is the NRO Office of Policy's research, policy analysis, and history component. CSNR products and activities help define and explain the discipline, practice, and history of national reconnaissance. CSNR functions are intended to help to provide NRO leadership with a historical context and conceptual focus for its policy and programmatic decisions. CSNR also responds to today's reality of an increasingly open NRO, and helps inform and educate the national reconnaissance community. By accomplishing its mission, CSNR supports the NRO's strategic goals to execute space reconnaissance acquisition and operations, transform sources and methods, and partner in delivering vital intelligence. The information in this publication may not necessarily reflect the official views of the Intelligence Community, the Department of Defense, or any agency of the U.S. -

Glomar” Is Such an Apt Name for Preemptive Denial of FOIA Claims1

Case 1:18-cv-02048-TSC Document 18-3 Filed 02/28/19 Page 1 of 2 Exhibit B 1 Why “Glomar” is such an apt name for preemptive denial of FOIA claims1 The invocation of a so-called Glomar response to Freedom of Information Act requests, though usually inappropriate, is oddly symbolic. The USNS Hughes Glomar Explorer was a ship built in 1971 under CIA’s Project Azorian to recover the Soviet submarine K-129 which sank in 1968. The CIA spent $1.68 billion ($10.63 billion in current value) in a no-bid contract to build the massive, sole- purpose ship. Glomar Explorer’s cover story was that it would “extract manganese nodules” from the ocean floor. But the nautical boondoggle ultimately failed. During an attempt to winch the K-129 to the surface, the submarine broke up, and the most-sought items such as codebooks and nuclear missiles were lost. The vessel was subsequently reflagged the GSF Explorer and roamed the seas like an albatross, searching for a buyer and a new purpose. The massive sums of taxpayer dollars that paid to build and sail the vessel were never recouped and in 2015 it was announced the ship would be sold for scrap. Ever since “boilerplate” refusals to properly respond to public interest FOIA requests about publicly known programs became known as “Glomar” responses. Essential details of Project Azorian were ultimately disclosed in the news media, starting with reporter Jack Anderson in the mid-1970's who claimed, "Navy experts have told us that the sunken sub contains no real secrets and that the project, therefore, is a waste of the taxpayers’ money."2 1 Excerpt from ECF 13-1, FOIA Case 1:15-cv-01431-TSC, pages 2-3 2 Robarge, David (March 2012). -

Ocean Margin Drilling Program

Appendix B Background on Deep Ocean Drilling for Scientific Purposes BACKGROUND ON DEEP OCEAN DRILLING FOR SCIENTIFIC PURPOSES THE MOHOLE EXPERIMENTAL DRILLING PROGRAM ● PHASE I Marine geologists and oceanographers have long desired to study samples from deep in the sediments and rocks beneath the ocean floor in order to extend man’s knowledge of the earth and its history. In 1957 a distinguished group of these scientists joined together in an informal association known as the American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC). This group concluded that the greatest advance in the earth sciences could be made by drilling through the crust of the earth to the mantle. This boundary was known as the Mohorovici Discontinuity (MOHO) - hence the name MOHOLE. By continuous coring and measurement of the characteristics of the sediments and rocks, many of the theories developed by indirect methods could be tested against the direct evidence obtained from the hole. It soon became evident that the goal could be reached most expeditiously by drilling in the deep ocean basins where the crust was known to be thinnest (18000 to 12000 feet) and the least drill penetration would be required. How- ever, in these locations the water depths ranged from 12000 to 18000 feet, thus requiring a drill string length equal to or greater than 30000 feet to reach the MOHO. This drill string requirement exceeded by 5000 feet the deep- est penetration achieved on land up to that time and the then current offshore drilling operations were limited to maximum water depths of about 600 feet. Undaunted by the formidable challenge posed by major advances required in the state-of-the-art of drilling at sea, the AMSOC group became a formal committee of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and obtained funds from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to investigate potential approaches to the problem. -

Sea-Bed Mineral Resource Development: Recent Activities of the International Consortia

ST/ESA/107 Department of International Economic and Social Affairs SEA-BED MINERAL RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT: RECENT ACTIVITIES OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONSORTIA UNITED NATIONS New York, 1980 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ST/ESA/107 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.80.II.A.9 Price: $U.S.2.00 PREFACE This survey of the deepsea mining consortia was prepared by the United Nations Department of International Economic and Social Affairs under a general mandate in the field of marine affairs that has been laid do™ in the resolutions of United Nations governing bodies since 1966. 1/ Specifically in the field of sea-bed minerals, the survey is responsive to interest expressed both by the General Assembly and the Economic and Social Council in various aspects of sea-bed mineral resource exploitation and to accompanying directives from these bodies to provide information periodically on latest developments. 2/ Recently, a detailed programme of work on sea-bed minerals was formulated by the Department of International Economic and Social Affairs, consisting of several discrete projects that address at a concrete, technical level a number of prominent issues and problems associated with sea-bed mineral development. One of these projects, which consists of the monitoring of the activities of the international deepsea consortia, has resulted in the present survey. Other projects, under way or soon to commence, deal with the data base for resource evaluation, nodule processing technology and the mine site concept in ocean mining. -

NSIAD-83-41 Uncertainties Surround Future of U.S. Ocean Mining

BY THECOMPTi70iLER GENERAL OF THEUNITED STATES Uncertainties Surround Future Of U.S. Ocean Mining In this report, GAO reviews Federal Govern- ment, private sector, and foreign competitor Involvement In ocean mmmg and exammes whether there IS a need to develoa U S ocean mining policy The Congress has Identified mrmng of the deep seabeds as a desirable alternative to foreign markets However, uncertalntressurround the future of ocean mu-ring These uncer- tainties stem from the absence of (1) a clear legal basis to assure direct access to deep seabed minerals, (2) an assessment that evaluates U S vulnerabrlrty to supply mter- ruptrons of exrstrng mineral markets, and (3) a policy decrsron of what the Federal role, If any, should be In promotmg ocean mining GAO IS recommending that the office of Science and Technology Policy perform assessments of U S strategic and crmcal mineral needs and the costs and benefits of alternative approaches, mcludrng ocean mrnmg, to reducing U S vulnerabrlrty to mineral source of supply drsruptrons GAO believes these assessments would benefit U S ocean mrnmg policy by provrdrng a framework for determining which of the approaches WIII require Federal assistance or intervention GAO/NSIAD-83-41 SEPTEMBER 6,1993 Request for copies of GAO reports should be sent to U S General Accountmg Offlce Document Handlmg and Information Services Faclhty PO Box 6015 Galthersburg, Md 20760 Telephone (202) 275 6241 The first five copies of mdwdual reports are free of charge AddItIonal copies of bound audit reports are $3 25 each -

Hughes Glomar Explorer

HUGHES GLOMAR EXPLORER An ASME Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark Houston, Texas July 20, 2006 Introduction The success of the Hughes Glomar Explorer proves that the impossible is, indeed, possible when talented engineers with the courage to take prudent risks are provided an incentive to stretch the state-of-the-art. The objective of the Hughes Glomar Explorer mission, retrieve a 2,000-ton (1,814-tonne) asymmetrical object from a water depth of 17,000 feet (5,182 meters), required a design incorporating unique solutions which were well beyond the state-of-the-art in numerous engineering and scientific disciplines, particularly mechanical engineering. For this reason the Hughes Glomar Explorer, as a complete deep-sea recovery system, has been designated an ASME Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. Grasping and raising a 2,000-ton (1,814-tonne) object in 17,000-feet (5,182-meters) of water in the central Pacific Ocean was a truly historic challenge requiring a recovery system of unprecedented size and scope. Major innovations and advances in mechanical engineering specifically required in the design of the Hughes Glomar Explorer include: 1. A large center well opening in the hull and a means of sealing it off so that the objective could be examined in dry conditions 2. A hydraulic lift system capable of hoisting a large, heavy load 3. A tapered heavy lift pipe string, including tool joints, designed, constructed and proof tested to exceptionally demanding standards 4. A “claw” with mechanically articulated fingers which used surface supplied sea water as a hydraulic fluid 5. A motion compensated and gimbaled work platform system that effectively isolated the suspended load from the roll, pitch and heave motions of the ship 6.