Footprints of the Templers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Oppenheim,Moshe (Moshe Op) Born 25 December 1926 In

1 Oppenheim , Moshe (Moshe Op) Born 25 December 1926 in Niederohle, Germany Made Aliya in 1939 Joined the Palmach in 1943 Joined the Palyam in 1945 This is the Way it Was The episode of the weapons of “J” Company, HaPortzim Battalion, Harel Brigade The story starts with a prelude… I made Aliya from Germany when I was 13 years old. This was just three months after the start of World War II. I arrived in Haifa on December 20, 1939. My brother, who was three years older than I, made Aliya three months earlier within the framework of Youth Aliya. My parents and two sisters were killed by the Germans, but this only became known to me some time later. In 1940 I was accepted as a student in the Max Fein Technical High School in Tel Aviv and started to learn metalworking. In 1941-42 there seemed to be a danger that the Germans might invade Palestine from the direction of Egypt and the sea, under the command of Field Marshal Rommel. I was a bit young but enlisted with almost the whole class, in the Hagana. I swore my loyalty to a fellow called Al Dema in the Borochov quarter of Givataim. Al Dema was the director of the Herzliya Gymnasium in Tel Aviv. We began training, with light weapons during the day and had field practice on Saturdays. We often stood watch at strategic locations to make certain that the Germans didn't try to land paratroopers there. The peak of our service was during the vacation period of the summer of 1942 when we were taken to an English camp at Tel Litvinsky and swore our loyalty to the English monarch. -

Memories of Palestine

MEMORIES OF PALESTINE Narratives of life in the Templer communities 1869-1948 Translated by Peter G. Hornung Heinz Arndt and others Published by Temple Society Australia 152 Tucker Road Bentleigh Victoria 3204 E-Mail [email protected] .au Tel. (03) 9557 6713 Fax (03) 9557 7943 www.templers.org 1 About the book This book contains 46 stories from different authors, 544 pages, 60 photographs and maps ISBN – 0958722986 Price A$40.00 GST inclusive Printed in Australia, Trendprint (Aust) Pty Ltd; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 This collection of stories is not a history book in the traditional sense, but it has much to do with our history. The individual contributions should convey to what extent Templers are in touch with their origins and their traditions. This is how the story came to be told: Palestine, home to several generations of Templers, had been lost. What with internment and deportation, the point of no return had truly been passed for many hundreds of people. The new beginning in unfamiliar Australia was not easy. But they made it; they found their way back from dispersal to rejoin each other. After all the terrible times, fathers and mothers in reunited families told their children about Palestine, about the land whence they had come and which they could not forget. This book is more about oral history than reference. You will ‘hear’ the people talk; you will listen to their anecdotes, take part in their highs and lows, their triumphs and their tragedies, and perhaps look deeply into their souls. -

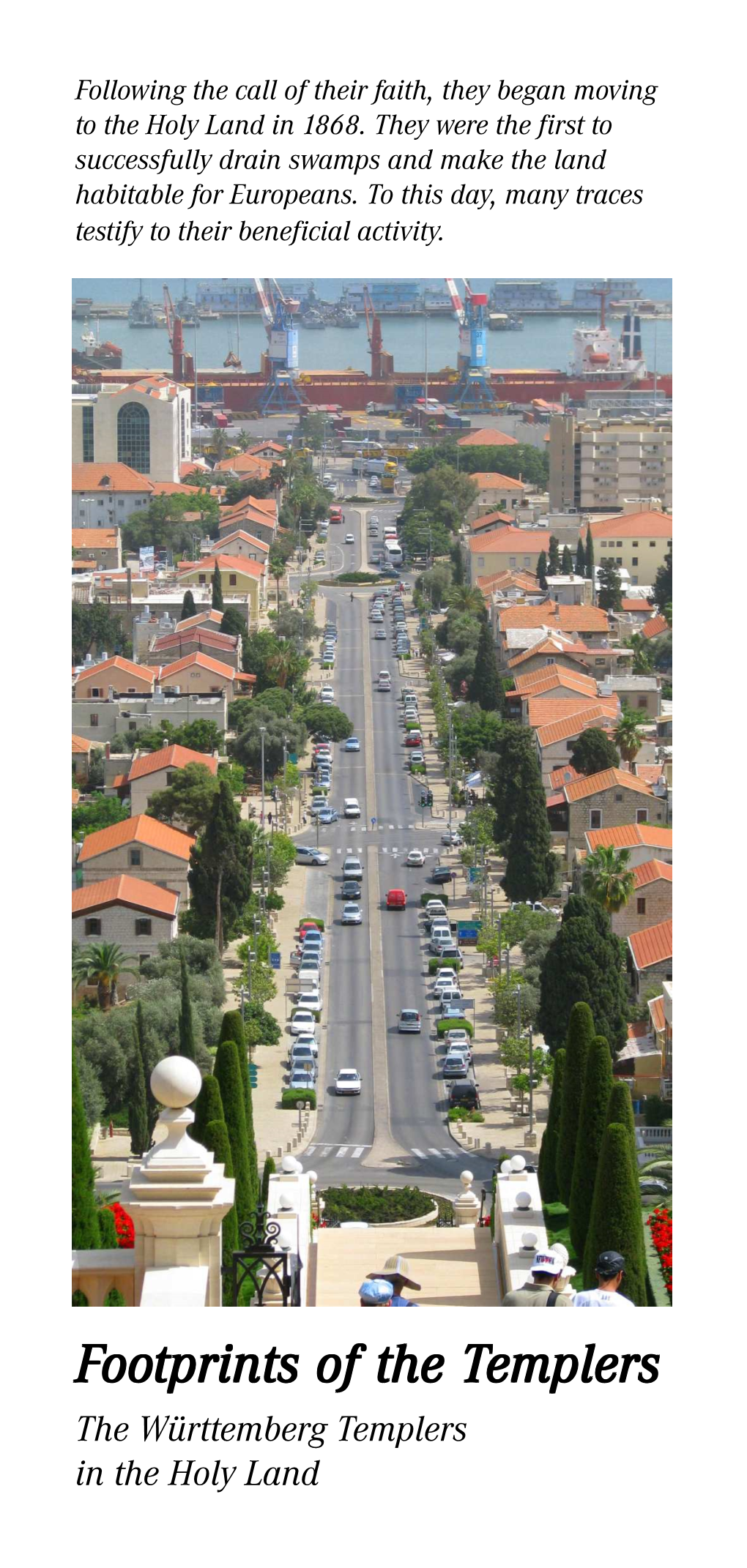

19-05 Tempelgesellschaft

1 COPYRIGHT: COPYRIGHT DiesesDieses Manuskript Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. geschützt. Es darf E ohnes darf Genehmigung ohne Genehmigung nicht verwertet nicht werden.verwertet Insbesondere werden. darf Insbesondere es nicht ganz darf oder es teilwe nicht iseganz oder oder in Auszügen teilweise oderabgeschrieben in Auszügen oder in sonstigerabgeschrieben Weise vervielfältigt oder in sonstiger werden. Weise Für vervielfältigRundfunkzwecket werden. darf dasFür Manuskript Rundfunkzwecke nur mit Genehmigungdarf das Manuskript von DeutschlandRadio nur mit Genehmigung / Funkhaus Berlin von Deutsch benutzt landradiowerden. Kultur benutzt werden. Deutschlandradio Kultur Zeitreisen am 19. Mai 2010 Redaktion: Peter Kirsten „Bis hierher hat der Herr geholfen“ Das Erbe der pietistischen Tempelgesellschaft in Israel Von Sigrid Brinkmann Atmo: Hafen Darauf Autorin: Ich stehe am Sderot Ben-Gurion, an einer breiten, baumbestandenen Allee, die von Häusern mit Satteldächern aus rotem Ziegelstein gesäumt wird. Ein paar Fußminuten entfernt löschen Schiffe ihre Fracht im Hafen, um dann weiter Kurs auf die Bucht von Akko zu nehmen. Am anderen Ende der Straße liegt das Eingangstor zum terrassenförmig angelegten Tempelgarten der Bahai. Majestätisch wirkt der dahinter aufragende Carmel- Berg. Auf dieser für den Nahen Osten so untypischen Panoramastraße begann vor etwas mehr als 140 Jahren das Siedlungsabenteuer einer deutschen Sekte. Musik einblenden: Rabih Abou.Khalil: „Selection“, track 7 CD: enja ENJ 9525 2 (2009) DLR-Code: 93-68651 Darauf Autorin: Vier Männer schickte die württembergische Tempelgesellschaft 1865 auf eine Expedition ins Heilige Land. Sie sollten die 2 Lebensbedingungen erkunden und prüfen, ob ein paar hundert, vielleicht tausend Pietisten dauerhaft in Palästina existieren könnten. Heftiger Streit mit der evangelischen Kirche hatte 1858 zum Ausschluss der Tempelgesellschaft geführt. -

A Case Study of the Temple Society Australia. by Irene

The dilemma ofadaptation and assimilation: a case study ofthe Temple Society Australia. by Irene Anne Bouzo Dip T (Prim) Burwood Teachers College Cert ofAdult Education Hawthorn Institute ofEducation Post Grad Dip Multicultural Education University ofNew England A thesis submitted for the Doctorate ofPhilosophy ofthe University ofNew England 28 March 2007 I certify that I am the sole author and that the substance ofthis thesis has not already been submitted for any degree and is not being currently submitted for other degrees. I certify that to the best ofmy knowledge that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. --- Signature Acknowledgments I extend my heartfelt thanks to the following people for their assistance and support: To my principal supervisor Professor Anne-Katrin Eckermann for the outstanding quality of her advice and guidance, her uplifting support through most difficult times and for challenging me to aspire to the highest potential. To my co-supervisor Dr Mariel Tisdell for invaluable advice and assistance with the German language and translations. To the Regional Council of the Temple Society Australia for the support and encouragement which included permission to conduct the research, and to the Archive Personnel for their kind and friendly assistance in the location of references. To the interview participants for their warm welcome, generosity and the depth of personal stories they shared. My thoughts are with those who have since passed away. May they rest in peace. To the many members of the Temple Society who contributed their wisdom and who read and commented on the manuscript. -

Lapid Organization & Tourism Division

World WIZO Lapid Organization & Tourism Division No. 109 August 2013 Dear Chavera, This issue of the "LAPID" is the last for the year 2013/5773. The High Holidays are approaching, and we are all getting ready to receive the New Year in high spirits and good health. In the section on Holidays you will find an article on the process of self examination and personal change that characterizes the period from the beginning of the month of Elul until the end of Yom Kippur. As with most Jewish holidays, food plays an important role but more importantly holiday celebrations are a highly effective means of binding families and passing on traditions. We have included a collection of family-favorite recipes courtesy of WIZO chaverot around the globe. Enjoy! "Successful Jewish Woman" pays homage to Leah Gottlieb, founder of Gottex, the swimsuit brand that has put Israel on the map of high fashion. Sticking to the theme of water, making a splash in Hollywood is the Israeli series "Hatufim" on which Channel 4's US hit "Homeland" is based. On the subject of the "The Jewish World" we present the fascinating story of the unique Jewish community of Iquitos in the Peurvian Amazon which is a true testimony to the survival of spirit, belief and heritage. Thinking Israel and Germany usually ends up with thinking Holocaust. Contrary to this, the "Templer Saga" highlights the positive contribution of the German Templers to the State of Israel. On a less optimistic note "Antisemitism" addresses the harsh reality of anti-Semitism and anti-Israeli sentiments Jewish community leaders are grappling with. -

Discovering Israel & Jordan

DISCOVERING ISRAEL & JORDAN Israel is the destination of a lifetime, a fascinating journey with pursuits to match every desire. Experience the country’s dynamic story with our comprehensive Discovering Israel & Petra tour, offering a unique mix of activities and authentic cultural encounters. This trip starts in Tel Aviv, the city that never sleeps, continuing north to explore sites along the Mediterranean coast, and on to the Galilee and Golan Heights. We then travel to the capital city of Jerusalem, rich in history and culture, and the dramatic vistas of the Negev desert before visiting the enchanting site of Petra in Jordan. Our exciting itinerary invites you to discover ancient and modern history, biblical sites and the cultural mosaic of contemporary Israel. TRAVEX tailors your journey for high profile travellers looking to enhance their visit with exclusive local experiences, insider access, exploration of ancient sites & meetings with fascinating people. We listen to you, designing made-to-order programs that exceed expectations with our TRAVEX personal touch. This program can be adapted to suit the needs of each client, customized for family travel or different religious orientations, and modified to accommodate any group size. Tell us your preferences and interests and we can together design your exclusive Israel Experience. DAY 1 Arrival to Israel. VIP assistance through arrival procedures at Ben Gurion Airport. Our VIP representative will meet you at the end of the jetway and escort you through the terminal, to passport control. Fast track service through passport control. Baggage claim procedures and escorting through customs to connect with your private transfer. -

What's on in Tel Aviv /May

WHAT'S ON IN TEL AVIV / MAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 KAZABLAN – PLAY THE KIDS WANT HOLOCAUST CHRIS CORNELL – JULIO IGLESIAS – WITH RUS SUBTITLES COMMUNISM – MEMORIAL EVE CONCERT CONCERT Cameri Theatre 8:30PM EXHIBITION (FREE) Mann Auditorium Menora Mivtachim Arena Museums of Bat Yam (All restaurants, cafes WILDLIFE 9:30PM 9PM Tue, Thu: 16:00-20:00 and shops will be closed PHOTOGRAPHER OF THE for the whole evening) HUNGARIAN DAYS ISRAELI FOLK DANCING Fri, Sat: 10:00-14:00 YEAR – EXHIBITION Until May 14 (FREE) (FREE) AT THE Eretz Israel Museum May 6-7 HATACHANA COMPOUND Until August 31 Hatachana Compound Every Saturday, 11:00AMPINK STAR JEWISH FOOTBALL PLAYERS IN GERMANY - EXHIBITION | May 2-9, Habima Square INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY FESTIVAL | Jaffa Port & Old City, Ongoing until May 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 ON THE RIVERS OF ITALIAN JEWISH INDEPENDENCE DAY "THEREFORE WE TRILOGIA PLUS – MIX ITZIK GALILI: BABYLON – THE RENAISSANCE – CELEBRATIONS HAVE GATHERED" OF CLASSICAL, JAZZ THE MAN OF THE SYMPHONIC SERIES EXHIBITION INDEPENDENCE DAY AND POP MUSIC HOUR – DANCE (Ullmann, Lavry, Lera BEACH Museum of the Jewish HAPPENING Mann Auditorium, 1PM Auerbach, Shostakovich) SEASON OPENS People (Beit Hatfutsot) 11:00-4:00 PM Tel Aviv Performing Rothschild Blvd (corner JAZZ ON BEN GURION Arts Center 8PM ANIMAL EXPRESSIONS of Herzl St) BLVD. –EXHIBITION MEMORIAL EVE (between Dizengoff & Ben Man and the Living World (All restaurants, cafes Yehuda streets) Museum, Ramat Gan and shops will be closed 12:00-2:00PM -

Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Vincent Lemire, Angelos Dalachanis

Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Vincent Lemire, Angelos Dalachanis To cite this version: Vincent Lemire, Angelos Dalachanis. Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840-1940: Opening New Archives, Revis- iting a Global City. BRILL, 2018, 10.1163/9789004375741. hal-02888585 HAL Id: hal-02888585 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02888585 Submitted on 19 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 9789004375741 Downloaded from Brill.com08/27/2018 12:58:10PM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 9789004375741 Downloaded from Brill.com08/27/2018 12:58:10PM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 9789004375741 Downloaded from Brill.com08/27/2018 12:58:10PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Spirit of Israel Tour

Jewish National Fund SPIRIT OF ISRAEL TOUR May 12-20, 2019 Sunday, May 12 – Arrival / Tel Aviv PM Welcome to Israel! Upon individual arrivals, meet your arranged transfer and head to your hotel in Tel Aviv, Israel’s most cosmopolitan city, right on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. In the evening, your journey will officially commence with a welcome dinner at a local restaurant. Overnight Carlton Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Itinerary is subject to change. Monday, May 13 - Tel Aviv / Jaffa AM Following breakfast at the hotel, visit the Ben-Gurion House, located in what was the first workers’ neighborhood, and now one of Tel Aviv’s liveliest neighborhoods. The house served as the residence of the Ben-Gurion family from 1931 until they settled in Kibbutz Sde-Boker, in 1953. Experience an unmediated perspective on Ben-Gurion’s way of life. Visit the house’s rooms, including his wife Paula’s room, where he spent his last days, and the second floor that was used solely by Ben- Gurion, with its four library rooms that include a collection of 20,000 books in ancient Greek, Latin, English, Hebrew, French, Turkish, German, and Russian. Proceed to Old Jaffa, one of the world’s oldest seaports, now home to a multi-ethnic community of Muslims, Christians, and Jews. See the ancient ruins, explore the restored artists’ quarter, and stroll through the winding alleyways while learning about the rich history of the area. Enjoy lunch and explore Jaffa’s flea market, boutique shops, galleries and cafés. PM Visit the Ayalon Institute, a secretive bullet factory established by the Haganah underground movement in 1945. -

Israel Update – Monday, July 3

Israel and the Middle East News Update Thursday, August 4 Headlines: Israel, US Say Progress Made in Military Aid Talks, Deal Expected Soon Hamas ‘Infiltrated Gazan Aid Group’, Stole Tens of Millions of Dollars Knesset Votes to Postpone Launch of New Public Broadcasting Corp. Ahead of Elections, Fatah Brags of Killing 11,000 Israelis Israel’s Arabs Want More Industrial Zones Cabinet to Vote on Giving Gaza a Port ISIS in Sinai Threatens to Turn Israel into a Graveyard IDF Destroys Homes of Sarona Terrorists Commentary: Project Syndicate: “Israel’s Government Hawks and Military Doves” By Daniel Kurtzer, Former U.S. Ambassador to Egypt and Israel Middle East Institute: “Israeli-Russian Relations: Respect and Suspect” By Eran Etzion, Former-Head of Policy Planning, Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 www.centerpeace.org ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● David Abreu, Associate Editor News Excerpts August 4, 2016 Ha’aretz Israel, US Say Progress Made in Aid Talks, Deal Expected Soon Following three days of intensive discussions in Washington, D.C. progress has been made in talks between Israel and the U.S. on the military agreement aid, but the two sides have yet to reach a deal. Senior American and Israeli officials expressed their optimism, telling Ha’aretz that most of the remaining gaps are technical, and that they believe that an agreement could soon be reached. Jerusalem Post Hamas ‘Infiltrated Gazan Aid Group’, Stole Tens of Millions Hamas infiltrated a large international aid organization operating in Gaza and redirected tens of millions of dollars - 60 percent - of the organization's budget to its military wing, the Shin Bet announced on Thursday, following an investigation that lasted almost two months. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction This case study of the Temple Society Australia tells the story of immigrant adaptation, language change and the development of an inter-cultural sense of belonging. The analysis is based on extensive interviews and surveys of sixty-nine long-term German speaking immigrants, their children and partners and includes active researcher participation in Templer community events. The settlement struggles of the first large-scale groups of established European immigrants in Australia, such as the Templers, during the mid twentieth century have largely been forgotten. Their triumphs and tragedies, their lost hopes and dreams in a country that was unprepared for such large numbers of non-English speaking people is no longer well known. Markus (2001) and Clyne (2003) point out that immigrants successfully built up ethno-specific community centres, clubs, religious centres, community languages schools and aged care facilities with tenacity and drive. They got jobs, built houses and their children excelled in education. Many saw opportunities in the market and used their overseas experience to open spectacularly successful businesses. Assimilationist thinking has closed the chapter of post-war immigrant settlement based on the assumption that such groups assimilated successfully. Their multiple identity formation remains shrouded by a policy that overemphasised conformity during the 1950s, 60s and 70s (Galligan and Roberts 2004, Jupp 2002). The traditional Australian attitude was that the host country bestowed benefits on immigrants who were prepared to learn the Australian way and assimilate. 17 From the 1970s to the 1990s, multiculturalism emphasised the maintenance of cultural and linguistic diversity (Galligan and Roberts 2004). -

Sunshine Tour: for Active Adults 55+

Jewish National Fund SUNSHINE TOUR: FOR ACTIVE ADULTS 55+ November 10 – 19, 2019 Chairs Hal Linden & Bernice Friedman Professional Matt Bernstein Sunday, November 10 – Arrival / Tel Aviv AM Welcome to Israel! Upon individual arrivals, meet your arranged transfer and head to the Sheraton Hotel in Tel Aviv, Israel’s most cosmopolitan city on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. PM This evening, your journey will officially commence with a welcome dinner in a private room at the hotel. Overnight Sheraton Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Itinerary is subject to change. Monday, November 11 – Tel Aviv / Center AM Following a delicious Israeli buffet breakfast at the hotel, depart to the Palmach Museum to learn about the strike-force arm of the Haganah, Israel’s pre-state underground defense organization. Experience a multimedia tour that will share the stories, struggles, and motivations of the brave men and women who made declaring an independent State of Israel possible. Meet with Palmach veterans and hear their personal stories. PM Depart for the trendy Sarona neighborhood, a former German Templar colony that has transformed into a thriving urban complex with new restaurants, cafés, and beautiful outdoor spaces. Enjoy lunch on your own in the Sarona Market, a contemporary urban market where Israel’s thriving culinary scene is on display. Continue to Ayalon Institute, a clandestine bullet factory that was established by the Haganah in 1945. As the largest bullet factory during that time, it produced 2.25 million bullets from 1946–1948, in complete secrecy. Tour the grounds of Ayalon, which played a major role in aiding the Jewish soldiers who fought for Israel’s Independence.