Sound Thought 2017 Conference Proceedings and Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

![My Girl [Intro] [Verse 1] I've Got Sunshine on a Cloudy Day When It's](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3453/my-girl-intro-verse-1-ive-got-sunshine-on-a-cloudy-day-when-its-293453.webp)

My Girl [Intro] [Verse 1] I've Got Sunshine on a Cloudy Day When It's

My Girl (The Temptations) [Intro] [Bridge] Hey, hey, hey [Verse 1] Hey, hey, hey I've got sunshine on a cloudy day Ooh, yeah When it's cold outside, I've got the month of May [Verse 3] I guess you'd say I don't need no money, fortune, or What can make me feel this way? fame I've got all the riches, baby, one [Chorus] man can claim My girl, my girl, my girl Well, I guess you'd say Talkin' 'bout my girl, my girl What can make me feel this way? [Verse 2] [Chorus] I've got so much honey, the bees My girl, my girl, my girl envy me Talkin' 'bout my girl, my girl I've got a sweeter song than the birds in the trees [Outro] Well, I guess you'd say I've got sunshine on a cloudy day What can make me feel this way? With my girl I've even got the month of May [Chorus] With my girl My girl, my girl, my girl Talkin' 'bout, talkin' 'bout, talkin' Talkin' 'bout my girl, my girl 'bout my girl 155 "My Girl" is a soul music song recorded by the Temptations for the Gordy (Motown) record label. Written and produced by the Miracles members Smokey Robinson and Ronald White, the song became the Temptations' first U.S. number-one single, and is today their signature song. Robinson's inspiration for writing this song was his wife, Miracles member Claudette Rogers Robinson. The song was included on the Temptations 1965 album The Temptations Sing Smokey. -

View Playbill

MARCH 1–4, 2018 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BOOK BY BERRY GORDY MUSIC AND LYRICS FROM THE LEGENDARY MOTOWN CATALOG BASED UPON THE BOOK TO BE LOVED: MUSIC BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE MUSIC, THE MAGIC, THE MEMORIES SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING OF MOTOWN BY BERRY GORDY MOTOWN® IS USED UNDER LICENSE FROM UMG RECORDINGS, INC. STARRING KENNETH MOSLEY TRENYCE JUSTIN REYNOLDS MATT MANUEL NICK ABBOTT TRACY BYRD KAI CALHOUN ARIELLE CROSBY ALEX HAIRSTON DEVIN HOLLOWAY QUIANA HOLMES KAYLA JENERSON MATTHEW KEATON EJ KING BRETT MICHAEL LOCKLEY JASMINE MASLANOVA-BROWN ROB MCCAFFREY TREY MCCOY ALIA MUNSCH ERICK PATRICK ERIC PETERS CHASE PHILLIPS ISAAC SAUNDERS JR. ERAN SCOGGINS AYLA STACKHOUSE NATE SUMMERS CARTREZE TUCKER DRE’ WOODS NAZARRIA WORKMAN SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN DAVID KORINS EMILIO SOSA NATASHA KATZ PETER HYLENSKI DANIEL BRODIE HAIR AND WIG DESIGN COMPANY STAGE SUPERVISION GENERAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER CHARLES G. LAPOINTE SARAH DIANE WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS NANSCI NEIMAN-LEGETTE CASTING PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT TOUR BOOKING AGENCY TOUR MARKETING AND PRESS WOJCIK | SEAY CASTING PORT CITY TECHNICAL THE BOOKING GROUP ALLIED TOURING RHYS WILLIAMS MOLLIE MANN ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC DIRECTOR/CONDUCTOR DANCE MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS ADDITIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ETHAN POPP & BRYAN CROOK MATTHEW CROFT ZANE MARK BRYAN CROOK SCRIPT CONSULTANTS CREATIVE CONSULTANT DAVID GOLDSMITH & DICK SCANLAN CHRISTIE BURTON MUSIC SUPERVISION AND ARRANGEMENTS BY ETHAN POPP CHOREOGRAPHY RE-CREATED BY BRIAN HARLAN BROOKS ORIGINAL CHOREOGRAPHY BY PATRICIA WILCOX & WARREN ADAMS STAGED BY SCHELE WILLIAMS DIRECTED BY CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT ORIGNALLY PRODUCED BY KEVIN MCCOLLUM DOUG MORRIS AND BERRY GORDY The Temptations in MOTOWN THE MUSICAL. -

May 1900) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 5-1-1900 Volume 18, Number 05 (May 1900) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 18, Number 05 (May 1900)." , (1900). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/448 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. — i/ObUIttE XVIII ^ /VlAy, 1900 SCHUBERT i^Uiwbe^ Editorials,.. i ■ 163 WITH SUPPLiEMEHT Questions and Answers,. 164 Home Notes, .164 d*44**44***44444*4****44*4***«*4*4t§**4<6«6**** A Studio Experience. W. J. Balt tell, ..164 4 Musical Items, ... '.J66 * New Publications, .167 * 4 The Greatest Difficulty for the Piano, 168 4 The Remoteness of Things. Titos. Tapper, ■ ■ . 169 4 A Scharwenka Anecdote, . 169 4 4 Thoughts, Suggestions, Advice, . 170 4 Five-minute Talk.' with Girls. Helena M. Maguire, 171 4 Haw to Handle S.ubfcorn Pupils. H. Patton,.171 4 Letters to Teachers. W. S. B. Matfuruis, 172 4 4 Too High \ims. E. -

Motown the Musical

EDUCATIONAL GUIDE C1 Kevin MccolluM Doug Morris anD Berry gorDy Present Book by Music and Lyrics from Berry gorDy The legenDary MoTown caTalog BaseD upon The BooK To Be loveD: Music By arrangeMenT wiTh The Music, The Magic, The MeMories sony/aTv Music puBlishing of MKoevinTown B yM Bcerrycollu gorDyM Doug Morris anD Berry gorDy MoTown® is a regisTereD TraPresentDeMarK of uMg recorDings, inc. Starring BranDon vicTor Dixon valisia leKae charl Brown Bryan Terrell clarK Book by Music and Lyrics from TiMoThy J. alex Michael arnolD nicholas chrisTopher reBecca e. covingTon ariana DeBose anDrea Dora presTBonerry w. Dugger g iiior Dwyil Kie ferguson iii TheDionne legen figgins DaryMarva M hicoKsT ownTiffany c JaaneneTalog howarD sasha huTchings lauren liM JacKson Jawan M. JacKson Morgan JaMes John Jellison BaseD upon The BooK To Be loveD: Music By arrangeMenT wiTh crysTal Joy Darius KaleB grasan KingsBerry JaMie laverDiere rayMonD luKe, Jr. Marielys Molina The Music, The Magic, The MeMories sony/aTv Music puBlishing syDney MorTon Maurice Murphy Jarran Muse Jesse nager MilTon craig nealy n’Kenge DoMinic nolfi of MoTown By Berry gorDy saycon sengBloh ryan shaw JaMal sTory eric laJuan suMMers ephraiM M. syKes ® JMuliusoTown Tho isM asa regisiii TereDanielD Tra DJ.eM waraTTK sof uMDgonal recorD wDeingsBBer, i, ncJr.. Scenic Design Costume Design LighStarringting Design Sound Design Projection Design DaviD Korins esosa BranDnonaTasha vic TKoraTz Dixon peTer hylensKi Daniel BroDie Casting Hair & Wig Design valisia leKae Associate Director Assistant Choreographer Telsey + coMpany charlcharles Brown g. lapoinTe scheleBryan willia TerrellMs clarK Brian h. BrooKs BeThany Knox,T icsaMoThy J. alex Michael arnolD nicholas chrisTopher reBecca e. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Mickey Stevenson

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Mickey Stevenson PERSON Stevenson, Mickey, 1937- Alternative Names: Mickey Stevenson; Life Dates: January 4, 1937- Place of Birth: Detroit, Michigan, USA Residence: West Hollywood, CA Work: CA Occupations: Music Executive Biographical Note Music executive Mickey Stevenson was born on January 4, 1937, in Detroit, Michigan, and raised by his mother, blues singer Kitty “Brown Gal” Stevenson, and stepfather Ted Moore. From the age of eight, Stevenson performed in a singing trio with his younger brothers. In 1950, the group won first place at Amateur Night at the Apollo Theater in New York City. However, Stevenson’s musical career halted in 1953 when his mother, the group’s coach and producer, when his mother, the group’s coach and producer, passed away from cancer. Stevenson attended Detroit’s Northeastern High School. Stevenson joined the U.S. Air Force in 1956, where he was part of a special unit that organized entertainment for the troops. While on furlough in 1958, Stevenson saw a performance by the Four Aims—later known as the Four Tops—which inspired him to leave the military and pursue a career in music. Stevenson joined the Hamptones, touring with famed bandleader Lionel Hampton. Upon his return to Detroit, Stevenson met Berry Gordy, who told him of his plans to start a record label. Stevenson briefly worked as a producer and songwriter for Carmen Carver Murphy’s gospel label, HOB Records, until 1959, when Gordy hired him to head the artists and repertoire department at Motown Records. As Motown’s A&R executive, Stevenson was responsible for talent scouting, auditions, and managing the artistic development of recording artists and songwriters. -

Call on Khrushchev to Halt Laos Threat

Weatirar Distribution Today Cloudy with drinle today; 17,800 Ugh, 40>, Partly cloudy to- BEDBANK night and tomorrow. Low to- night, »». High tomorrow, S0>. 1 Independent Daily f See Weather page Z. (^ MONOAYTHKIVOHJlUDAY-lSrim J REGISTER SH 1-0010 iMUcd dtlly. Mondcy through FrlA*y. Second C1&H Poitsgt RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 1961 35c PER WEEK VOL. 83, NO. 187 Paid it Ked Bisk »nd at A&UUonil MUlln( OUlcei. 7c PER COPY BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Call on Khrushchev To Halt Laos Threat Macniillaii Off To America But U.S. LONDON (AP)-Prime Min- ister Harold Macmillan left by air today for a 19-day visit to Readies the United States, Canada and 1 the West Indies. He said he FOR RESEARCH INTO THE FUTURE — Aerial photo of th» Bell Labs Research Center, Holmdel Township, shows has "much to talk about" with building in its present-stage of construction — hearing completion. Structure in rear is 35,000-square-foot service President Kennedy. AidMove and maintenance building. Engineers say the center, to be ona of the largest research installations in the world, Aides laid that despite the urgency of the Laotian crisis, will be completed by October or November of this year and ready for occupancy early next year. WASHINGTON (AP) — Macmillan is adhering to his President Kepfiedy looked original schedule calling for a visit first to the West Indies hopefully to Soviet Premier Nearlng Completion in Holmdel «nd meetings with Kennedy Nikita Khrushchev today April 5-6. But the aides said if to call a halt to the Soviet- the situation in Laos got worse backed rebel offensive in of Premier Khrushchev reject- Bell Labs Center to Employ 2,500 ed the latest British-American Laos and avert mounting proposal of a cease-fire fol- danger of a U. -

MUS 125 SYLLABUS(Spring 2016)

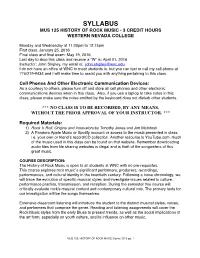

SYLLABUS MUS 125 HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC - 3 CREDIT HOURS WESTERN NEVADA COLLEGE Monday and Wednesday at 11:00pm to 12:15pm First class: January 25, 2016 Final class and final exam: May 19, 2016 Last day to drop this class and receive a “W” is: April 01, 2016 Instructor: John Shipley, my email is: [email protected] I do not have an office at WNC to meet students in, but you can text or call my cell phone at 775/219-9434 and I will make time to assist you with anything pertaining to this class. Cell Phones And Other Electronic Communication Devices: As a courtesy to others, please turn off and store all cell phones and other electronic communications devices when in this class. Also, if you use a laptop to take notes in this class, please make sure the noise emitted by the keyboard does not disturb other students. *** NO CLASS IS TO BE RECORDED, BY ANY MEANS, WITHOUT THE PRIOR APPROVAL OF YOUR INSTRUCTOR. *** Required Materials: 1) Rock 'n Roll, Origins and Innovators by Timothy Jones and Jim McIntosh 2) A Pandora Apple Music or Spotify account or access to the music presented in class, i.e. your own or friend’s record/CD collection. Another resource is YouTube.com, much of the music used in this class can be found on that website. Remember downloading audio files from file sharing websites is illegal and is theft of the songwriters of this great music. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The History of Rock Music is open to all students at WNC with no pre-requisites. -

Leonardo Man Dies As Roadstand Burns

•etiher DISTRIBUTION f Ob mnfa* tnfett cteartag REDBANK TODAY ftfr tAmm, W«i» lo dte tts. 1M0*, (jar, to* «t to H. f. 23,800 •W, mmy, Ufh Mr 71. Friday, Mr and nOd. Set weatb- J DIAL 741-0010 Unit! tuir. KoMmy Uuran ftU»T. Meoia Clm PMUH VOL. 86, NO. 206 Paid U &d BUM %nt M AMttlcati IUlUa« OJflcn. RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 15, 18(64 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Merger of2Matawans? - Forget ItiT MATAWAN —If Strathmore Civic Association think* that The general reasoning: Why should Matawan Borough Leonardo Man Dies Martawan Borough is going to merge with Matawan Town- take over all of Matwan Township's problems, especially its ship forget it. future problems, to be realized when the full impact of The issue came up during a Borough Council session last Strathmore will be felt, within a few years ? night and was cold-shouldered off the agenda. Mr. Hyrne indicated last night that merger in effect would mean annexation of the borough by the township, and he put Former Mayor Ralph R. Dennis asked what could be done borough minds at ease by noting that this cannot be done, to stop the "movement." under state law, without consent of th« governing body (in both Mayor Edward E. Hyrne didn't see any need to bother towns) and 60 per cent voter approval at referendum, As Roadstand Burns about it. Officials in both parties here agree that such consents By JACQUELINE ALBAN table stand gutted by a brief, hospital," Mrs. Pittius told a cian, who was called to ths Sirathmore Civic Association (in Mataivan Township) has "will never come about." ) LEONARDO - A man died last roaring blaze which took local reporter, her voice trembling. -

Year 1963 Dean Martin LP

Year 1963 Dean Martin LP “Dean “Tex” Martin – Country Style” 414 Martin, Dean Dean “Tex” Martin - Country Style Reprise R9-6061 (US) 1.1963 I’m so lonesome I could cry (piano) – Face in a crowd (piano) – Things (background piano) – Room full of roses (no piano) – I walk the line (no piano) – My heart cries for you (piano!!) – Any time (piano) – Shutters and boards (piano) – Blue, blue day (piano?) – Singing the blues (piano) – Hey, Good Lookin’ (no piano) – Ain’t gonna try anymore (piano!!!) – Lots of Leon all over! James Burton on guitar. Rec. date: Face in a crowd - Ain’t gonna try anymore - Shutters & Boards - Singing The Blues - Face In The Crowd - Dec. 20, 1962 The label states that the year of release was 1961!!?? - Arr. & cond. Don Costa – prod. Jimmy Bowen? Bobby “Blue” Bland – LP 645 Bland, Bobby Call On Me/That’s The Way Love Is Duke 360 (US) 2.1963 Leon background piano on both? Dean Martin LP “Dean “Tex” Martin – Rides Again” 543 Martin, Dean Dean “Tex” Martin - Rides Again Reprise R-6085 (US) 4.1963 I’m gonna change everything (no piano) – Candy kisses (piano!!) – Rockin’ alone (in an old rocking chair) (piano) – Just a little lovin’ (background piano) – I can’t help it (if I’m still in love with you) (piano) – My sugar’s gone (piano!!) – Corrine, Corrina (piano!) – Take good care of her (piano) – The middle of the night is my cryin’ time (piano!!) – From lover to loser (piano!) – Bouquet of roses (piano) – Second hand Rose (piano!!) – Lots of Leon all over! Arr. -

The History of the Record Label Motown AARP Magazine / December 2018-January 2019

archived as http://www.stealthskater.com/Documents/Motown_01.doc (also …Motown_01.pdf) => doc pdf URL-doc URL-pdf the history of the Record Label Motown AARP magazine / December 2018-January 2019 By Touré In the beginning, there was Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown records. A writer and producer of popular music that he hoped would one day reach all of young America. He was a man known for his impeccable ear and relentless drive. So it's not surprising that the second act that Gordy signed to his label was teenage composer William "Smokey" Robinson and his singing group the Miracles. - 1 - Like Gordy, Robinson was a prolific creator. He's now credited with over 4,000 songs and dozens of top-40 hits including "My Girl" for the Temptations, "My Guy" for Mary Wells, and "Ain't That Peculiar" for Marvin Gaye. But Robinson went on to sing many of the timeless hits which he created (for example, "The Tracks of My Tears", "I Second That Emotion", and "The Tears of a Clown"). He also became a Motown vice-president, producer, and talent scout. The image of Motown to this day is tied up with image of Smokey Robinson. Both are associated with class and taste and the ability to cross over to white audiences without ever losing the love and admiration of black fans. Robinson earned his place in the Rock&Roll Hall-of-Fame and the Songwriters Hall-of-Fame and has been honored by the Kennedy center. 2 years ago he received the Library of Congress' Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. -

Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files Includes Updated

The Great R&B Pioneers Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files 2020 The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files - page 1 The Great R&B Pioneers Is this the Top Ten ”Super Chart” of R&B Hits? Ranking decesions based on information from Big Al Pavlow’s, Joel Whitburn’s, and Bill Daniels’ popularity R&B Charts from the time of their original release, and the editor’s (of this work) studies of the songs’ capabilities to ”hold” in quality, to endure the test of time, and have ”improved” to became ”classic representatives” of the era (you sure may have your own thoughts about this, but take it as some kind of subjective opinion - with a serious try of objectivity). Note: Songs listed in order of issue date, not in ranking order. Host: Roy Brown - ”Good Rocking Tonight” (DeLuxe) 1947 (youtube links) 1943 Don’t Cry, Baby (Bluebird) - Erskine Hawkins and his Orchestra Vocal refrain by Jimmy Mitchell (sic) Written by Saul Bernie, James P. Johnson and Stella Unger (sometimes listed as by Erskine Hawkins or Jmmy Mitchelle with arranger Sammy Lowe). Originally recorded by Bessie Smith in 1929. Jimmy 1. Mitchell actually was named Mitchelle and was Hawkins’ alto sax player. Brothers Paul (tenorsax) and Dud Bascomb (trumpet) played with Hawkins on this. A relaxed piano gives extra smoothness to it. Erskine was a very successful Hawkins was born in Birmingham, Alabama. Savoy Ballroom ”resident” bandleader and played trumpet. in New York for many years.