Detroit Blues Women Michael Duggan Murphy Wayne State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ 1967-06-18 P-1 --------- 1967-06-18 / CP010340 / CS05917 Jimi Hendrix at Monterey Pop Festival - Monterey, CA Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Monterey Pop Festival Items: Original poster (Original artwork) Edition 1 / CP010340 / CS05917 (14 x 20) Performers: 1967-06-18: Monterey Pop Festival Jimi Hendrix ------------------------------ 1967-06-18 P --------- 1967-06-18 / CP060692 / CP060692 Monterey Pop Festival (Original Art) Notes: Original Art Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Monterey Pop Festival Items: Original poster / CP060692 / CP060692 (14 x 20) Performers: 1967-06-18: Monterey Pop Festival Jimi Hendrix ------------------------------ FW-BG-159 1968-02-06 P-1 --------- 1968-02-06 / FW BG-159 CP007260 / CP02510 Byrds, Michael Bloomfield at Fillmore West - San Francisco, CA Private Notes: BG-CD(+BG-158) BG-OP-1-Signed-Tuten A- 50- Artist: Randy Tuten Venue: Fillmore West Promoter: Bill Graham Original Series Items: Original poster FW-BG-159 Edition 1 / CP007260 / CP02510 Description: 1 original (14 x 21-3/4) Price: 100.00 Postcard FW-BG-159 Edition 1 / CP007858 / CP03102 Description: original, postal variations, double with BG158 (7 -

April 2019 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Hi Blues Fans, The final ballots for the 2019 WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Best of the Blues (“BB Awards”) Proud Recipient of a 2009 of the Washington Blues Society are due in to us by April 9th! You Keeping the Blues Alive Award can mail them in, email them OFFICERS from the email address associ- President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] ated with your membership, or maybe even better yet, turn Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] them in at the April Blues Bash Secretary, Open [email protected] (Remember it’s free!) at Collec- Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] tor’s Choice in Snohomish! This Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] is one of the perks of Washing- ton Blues Society membership. DIRECTORS You get to express your opinion Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] on the Best of the Blues Awards Membership, Open [email protected] nomination and voting ballots! Education, Open [email protected] Please make plans to attend the Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] BB Awards show and after party Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] this month. Your Music Director Amy Sassenburg and Vice President Advertising, Open [email protected] Rick Bowen are busy working behind the scenes putting the show to- gether. I have heard some of their ideas and it will be a stellar show and THANKS TO THE WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY 2017 STREET TEAM exceptional party! True Tone Audio will provide state-of-the-art sound, Downtown Seattle, Tim & Michelle -

Gedanken Über "Sweet Home Chicago"

Gedanken über "Sweet Home Chicago" Bei der Titelauswahl für "BlueSimon Special Vol.4 - Recorded In Chicago 1945 - 1955" bin ich naturgemäß auf diesen Song gestoßen, habe aber keine Aufnahme gefunden, die in den Zeitrahmen gepasst hätte. Jimmy McCracklin's Coverversion (als "Baby Don't You Want To Go" für Globe Records, 1945) hätte zwar gepasst, wurde aber in Los Angeles eingespielt. Roosevelt Sykes' "Sweet Old Chicago" (Imperial Records 5347, 1954) ebenfalls, ist aber in New Orleans aufgenommen. BoBo Jenkins Version (als "Baby Don't You Want To Go" für Fortune Records) ist aus 1956 und aus Detroit, passt also in zweierlei Hinsicht nicht. Bleibt nur David "Honeyboy" Edwards Aufnahme für Chess Records aus 1953, aber die ist meines Wissens nie veröffentlicht worden. Allerdings muss ich zugeben, dass ich auch eine in jeder Hinsicht passende Version nicht mit einbezogen hätte, war ich doch bemüht, weniger Bekanntes aus der Dekade auf die CDs zu bringen. "Sweet Home Chicago" ist neben einigen anderen Songs wohl einer der bekanntesten (und abgedroschensten) Bluestitel aller Zeiten, nicht zuletzt wegen der Popversion der Blues Brothers. A propos Popversion: Robert Johnson's legendäre Platte, aufgenommen 1936 und veröffentlicht 1937 als Vocalion 03601 war damals auch Popmusik und wurde eingespielt, um Geld zu verdienen. Also weniger Geld für den Künstler, sondern vielmehr für die Plattenfirma, die allerdings wegen der schlechten Verkaufszahlen einigermaßen enttäuscht gewesen sein dürfte. Johnson war aber immerhin bekannt genug, um von John Hammond für die "Spirituals To Swing" Konzerte jeweils um Weihnachten 1938 und 1939 ausgewählt zu werden. Seine musikalische Qualität ist bis heute unumstritten, seine Popularität war aber mehr auf seine Liveauftritte zurück zu führen, bei denen er zumeist mit anderen Musikern seiner Zeit in den verschiedensten Joints spielte. -

January 2021 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

Bluesletter J W B S . Nick Vigarino Still Rocks the House! Live at the US Embassy: Blues Happy Hour Remembering Jimmy Holden LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans, Proud Recipient of a 2009 I’m opening my letter with Keeping the Blues Alive Award another remembrance of another friend lost in our 2021 OFFICERS blues community. I have had to President, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org do this a few too many times Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected]@wablues.org lately and it is a reminder of Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected]@wablues.org how fragile life is and how Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected]@wablues.org important it is to live every day Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected]@wablues.org and make as many memories as you can. 2021 DIRECTORS Jimmy Holden passed away recently. I know there are many music Music Director, Open [email protected]@wablues.org fans who have great memories of Jimmy and his many performances Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected]@wablues.org and he touched many hearts with warmth, humor and melody. I will Education, Open [email protected]@wablues.org miss Jimmy for all of his wonderful stories about his travels. He Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected]@wablues.org traveled far and wide and we shared experiences we had both had Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org in multiple different localities around the world. Our conversations Advertising, Open [email protected]@wablues.org often lead to stories about adventures in Hong Kong, Thailand and other exotic places. -

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ P --------- / CP060727 / CP060727 20th Anniversary Notes: The original art, done by Gary Grimshaw for ArtRock Gallery, in San Francisco Benefit: First American Tour 1969 Artist: Gary Grimshaw Promoter: Artrock Items: Original poster / CP060727 / CP060727 (11 x 17) Performers: : Led Zeppelin ------------------------------ GBR-G/G 1966 T-1 --------- 1966 / GBR G/G CP010035 / CS05131 Free Ticket for Grande Ballroom Notes: Grande Free Pass The "Good for One Free Trip at the Grande" pass has more than passing meaning. It was the key to distributing the Grande postcards on the street and in schools. Volunteers, mostly high-school-aged kids, would get a stack of cards to pass out, plus a free pass to the Grande for themselves. Russ Gibb, who ran the Grande Ballroom, says that this was the ticket, so to speak, to bring in the crowds. While posters in Detroit did not have the effect that posters in San Francisco had, and handbills were only somewhat better, the cards turned out to actually work best. These cards are quite rare. Artist: Gary Grimshaw Venue: Grande Ballroom Promoter: Russ Gibb Presents Items: Ticket GBR-G/G Edition 1 / CP010035 / CS05131 Performers: 1966: Grande Ballroom ------------------------------ GBR-G/G P-01 (H-01) 1966-10-07 P-1 -- ------- 1966-10-07 / GBR G/G P-01 (H-01) CP007394 / CP02638 MC5, Chosen Few at Grande Ballroom - Detroit, MI Notes: Not the very rarest (they are at lest 12, perhaps as 15-16 known copies), but this is the first poster in the series, and considered more or less essential. -

Fréhel and Bessie Smith

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 9-18-2018 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Jackson, Tiffany Renée, "Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1946. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1946 Fréhel and Bessie Smith: A Cross-Cultural Study of the French Realist Singer and the African American Classic Blues Singer Tiffany Renée Jackson, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 ABSTRACT In this dissertation I explore parallels between the lives and careers of the chan- son réaliste singer Fréhel (1891-1951), born Marguerite Boulc’h, and the classic blues singer Bessie Smith (1894-1937), and between the genres in which they worked. Both were tragic figures, whose struggles with love, abuse, and abandonment culminated in untimely ends that nevertheless did not overshadow their historical relevance. Drawing on literature in cultural studies and sociology that deals with feminism, race, and class, I compare the the two women’s formative environments and their subsequent biographi- cal histories, their career trajectories, the societal hierarchies from which they emerged, and, finally, their significance for developments in women’s autonomy in wider society. Chanson réaliste (realist song) was a French popular song category developed in the Parisian cabaret of the1880s and which attained its peak of wide dissemination and popularity from the 1920s through the 1940s. -

The Historymakers: a New Primary Source for Scholars

The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Julieanna L. Richardson Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow Great Cities Institute College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 A Great Cities Institute Working Paper April 2007 The Great Cities Institute The Great Cities Institute is an interdisciplinary, applied urban research unit within the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Its mission is to create, disseminate, and apply interdisciplinary knowledge on urban areas. Faculty from UIC and elsewhere work collaboratively on urban issues through interdisciplinary research, outreach and education projects. About the Author Julieanna Richardson is the Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow at The Great Cities Institute of the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also founder and Executive Director of The HistoryMakers, an oral history archive founded in 1999. She can be reached at [email protected]. Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 The views expressed in this report represent those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Great Cities Institute or the University of Illinois at Chicago. This is a working paper that represents research in progress. Inclusion here does not preclude final preparation for publication elsewhere. Great Cities Institute (MC 107) College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago 412 S. Peoria Street, Suite 400 Chicago IL 60607-7067 Phone: 312-996-8700 Fax: 312-996-8933 http://www.uic.edu/cuppa/gci UIC Great Cities Institute The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Abstract This paper explores the possibilities of increasing the use and accessibility of The HistoryMakers’ video oral history archive. -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy. -

CONSTRUCTING TIN PAN ALLEY 17 M01 GARO3788 05 SE C01.Qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 18

M01_GARO3788_05_SE_C01.qxd 5/26/10 4:35 PM Page 15 Constructing Tin Pan 1 Alley: From Minstrelsy to Mass Culture The institution of slavery has been such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the roots of our popular music embedded in this tortured legacy. Indeed, the first indige- nous U.S. popular music to capture the imagination of a broad public, at home and abroad, was blackface minstrelsy, a cultural form involving mostly Northern whites in blackened faces, parodying their perceptions of African American culture. Minstrelsy appeared at a time when songwriting and music publishing were dispersed throughout the country and sound record- The institution of slavery has been ing had not yet been invented. During this period, there was an such a defining feature of U.S. history that it is hardly surprising to find the important geographical pattern in the way music circulated. Concert roots of our popular music embedded music by foreign composers intended for elite U.S. audiences gener- in this tortured legacy. ally played in New York City first and then in other major cities. In contrast, domestic popular music, including minstrel music, was first tested in smaller towns, then went to larger urban areas, and entered New York only after success elsewhere. Songwriting and music publishing were similarly dispersed. New York did not become the nerve center for indigenous popular music until later in the nineteenth century, when the pre- viously scattered conglomeration of songwriters and publishers began to converge on the Broadway and 28th Street section of the city, in an area that came to be called Tin Pan Alley after the tinny output of its upright pianos. -

View Playbill

MARCH 1–4, 2018 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS BOOK BY BERRY GORDY MUSIC AND LYRICS FROM THE LEGENDARY MOTOWN CATALOG BASED UPON THE BOOK TO BE LOVED: MUSIC BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE MUSIC, THE MAGIC, THE MEMORIES SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING OF MOTOWN BY BERRY GORDY MOTOWN® IS USED UNDER LICENSE FROM UMG RECORDINGS, INC. STARRING KENNETH MOSLEY TRENYCE JUSTIN REYNOLDS MATT MANUEL NICK ABBOTT TRACY BYRD KAI CALHOUN ARIELLE CROSBY ALEX HAIRSTON DEVIN HOLLOWAY QUIANA HOLMES KAYLA JENERSON MATTHEW KEATON EJ KING BRETT MICHAEL LOCKLEY JASMINE MASLANOVA-BROWN ROB MCCAFFREY TREY MCCOY ALIA MUNSCH ERICK PATRICK ERIC PETERS CHASE PHILLIPS ISAAC SAUNDERS JR. ERAN SCOGGINS AYLA STACKHOUSE NATE SUMMERS CARTREZE TUCKER DRE’ WOODS NAZARRIA WORKMAN SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN DAVID KORINS EMILIO SOSA NATASHA KATZ PETER HYLENSKI DANIEL BRODIE HAIR AND WIG DESIGN COMPANY STAGE SUPERVISION GENERAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER CHARLES G. LAPOINTE SARAH DIANE WORK LIGHT PRODUCTIONS NANSCI NEIMAN-LEGETTE CASTING PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT TOUR BOOKING AGENCY TOUR MARKETING AND PRESS WOJCIK | SEAY CASTING PORT CITY TECHNICAL THE BOOKING GROUP ALLIED TOURING RHYS WILLIAMS MOLLIE MANN ORCHESTRATIONS MUSIC DIRECTOR/CONDUCTOR DANCE MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS ADDITIONAL ARRANGEMENTS ETHAN POPP & BRYAN CROOK MATTHEW CROFT ZANE MARK BRYAN CROOK SCRIPT CONSULTANTS CREATIVE CONSULTANT DAVID GOLDSMITH & DICK SCANLAN CHRISTIE BURTON MUSIC SUPERVISION AND ARRANGEMENTS BY ETHAN POPP CHOREOGRAPHY RE-CREATED BY BRIAN HARLAN BROOKS ORIGINAL CHOREOGRAPHY BY PATRICIA WILCOX & WARREN ADAMS STAGED BY SCHELE WILLIAMS DIRECTED BY CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT ORIGNALLY PRODUCED BY KEVIN MCCOLLUM DOUG MORRIS AND BERRY GORDY The Temptations in MOTOWN THE MUSICAL. -

Clyde Mcphatter 1987.Pdf

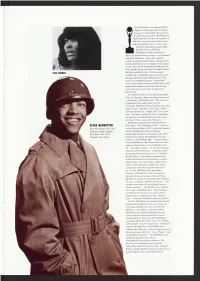

Clyde McPhatter was among thefirst | singers to rhapsodize about romance in gospel’s emotionally charged style. It wasn’t an easy stepfor McP hatter to make; after all, he was only eighteen, a 2m inister’s son born in North Carolina and raised in New Jersey, when vocal arranger and talent manager Billy | Ward decided in 1950 that I McPhatter would be the perfect choice to front his latest concept, a vocal quartet called the Dominoes. At the time, quartets (which, despite the name, often contained more than four members) were popular on the gospel circuit. They also dominated the R&B field, the most popular being decorous ensembles like the Ink Spots and the Orioles. Ward wanted to combine the vocal flamboyance of gospel with the pop orientation o f the R&B quartets. The result was rhythm and gospel, a sound that never really made it across the R &B chart to the mainstream audience o f the time but reached everybody’s ears years later in the form of Sixties soul. As Charlie Gillett wrote in The Sound of the City, the Dominoes began working instinctively - and timidly. McPhatter said, ' ‘We were very frightened in the studio when we were recording. Billy Ward was teaching us the song, and he’d say, ‘Sing it up,’ and I said, 'Well, I don’t feel it that way, ’ and he said, ‘Try it your way. ’ I felt more relaxed if I wasn’t confined to the melody. I would take liberties with it and he’d say, ‘That’s great.