Oral History Interview with Mary Giles, 2006 July 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

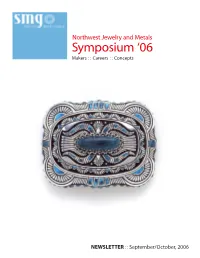

Symposium ‘06 Makers : : Careers : : Concepts

Northwest Jewelry and Metals Symposium ‘06 Makers : : Careers : : Concepts NEWSLETTER :: September/October, 2006 Makers : : Careers : : Concepts On behalf of the Seattle Metals Guild we look forward to seeing you at our event this year entitled Makers :: Careers :: Concepts. The Symposium committee has sought diverse presentations about these three categories hoping to appeal to widely different tastes. Yet perhaps each one of us is a maker and also a conceptualist AND a career minded person, merging many tastes. Might not a collector of art jewelry, who happens to be a business executive, be engaged with our three categories just like a beginning metals student? Of course they are, for we are all brought together by that great cultural bonding agent, art and its creative process. Let us share our different tastes and celebrate our common passions as we gather for a day all about art! We are excited to be part of this grand adventure and pleased to have attracted not only our esteemed speakers but the following organizations, among others, who are contributing toward our programs: The Bellevue Arts Museum The Allied Arts Foundation The Pratt Fine Arts Center Northwest Designer Craftsmen Artist Trust The Northwest Bead Society Facere Jewelry Art Gallery Jewelry Resource and Supply Allcraft Denise Wallace (Chugach Aleut) and Samuel Wallace: Female Mask with Goggles pin/pendant. 1996 Newsletter cover image: Sterling silver and turquoise Belt buckle by Lee Yazzie, Navajo. 2004 2 www.seattlemetalsguild.org The Eleventh Annual Northwest Jewelry and Metals Symposium 2006 Makers : : Careers : : Concepts Mark your calendars for Saturday October 21, 2006, from 8:30am to 6:00pm, and join us at the Seattle Asian Art Museum in lovely Volunteer Park. -

The Magazine of the Museum of Texas Tech University in This Issue | Fall-Winter 2017

The Magazine of the Museum Mof Texas Tech University In This Issue | Fall-Winter 2017 Bringing the Abstract Heroes of the Postosuchus: Special Needs Art Meets Holocaust T. Rex of the Community to Atmospheric Triassic the Museum Science The Magazine of The Texas Tech University Museum M The Magazine of the Museum is for Museum of Texas Tech University M Fall/Winter 2017 2 Staff Publisher and Executive Editor M=eC Gary Morgan, Ph.D. Copy Editor Daniel Tyler Stakeholder engagement for a university Editorial Committee Sally Post, Jill Hoffman Ph.D. museum is a continuum between the university Design (Campus) and the Community. The Museum Armando Godinez Jr. must engage with the Campus; it must engage M is a biannual publication of the Museum of Texas Tech University. with the Community; and it must facilitate 3301 4th St, Lubbock, TX 79409 Phone: 806.742.2490 engagement between Campus and Community. www.museum.ttu.edu All rights reserved. Museum (M) equals engagement (e) ©Museum of Texas Tech University 2017 by Campus (C) and by Community (C). Cover Photo: Harvey Chick The Texas Liberator: Witness to the Holocaust 2 | FAll/Winter 2017 Museum at sunrise with desert agave casting shadows. Photo: Ashley Rodgers Fall/Winter 2017 | 3 M The Magazine of The Texas Tech University Museum 12 Lessons Large and Small By Deborah Bigness 16 Beauty Abounds By Marian Ann J. Montgomery 22 Inside M Bringing the Special Needs Community to the Museum M News . 7 By Bethany Chesire Light Up Lubbock. 9 Genetic Resources Collection . 11 25 Extending Creative Visions . -

CHARON KRANSEN ARTS 817 WEST END AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10025 USA PHONE: 212 627 5073 FAX: 212 663 9026 EMAIL: [email protected]

CHARON KRANSEN ARTS 817 WEST END AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10025 USA PHONE: 212 627 5073 FAX: 212 663 9026 EMAIL: [email protected] www.charonkransenarts.com AUGUST. 2020 A JEWELER’S GUIDE TO APPRENTICESHIPS: HOW TO CREATE EFFECTIVE PROGRAMS suitable for shop owners, students as well as instructors, the 208 page volume provides detailed, proven approaches for finding , training and retaining valuable employees. it features insights into all aspects of setting up an apprenticeship program, from preparing a shop and choosing the best candidates to training the apprentice in a variety of common shop procedures. an mjsa publication. $ 29.50 ABSOLUTE BEAUTY – 2007catalog of the silver competition in legnica poland, with international participants. the gallery has specialized for 30 years in promoting contemporary jewelry. 118 pages. full color. in english. $ 30.00 ADDENDA 2 1999- catalog of the international art symposium in norway in 1999 in which invited international jewelers worked with jewelry as an art object related to the body. in english. 58 pages. full color. $ 20.00 ADORN – NEW JEWELLERY - this showcase of new jewelry offers a global view of exciting work from nearly 200 cutting-edge jewelry designers. it highlights the diverse forms that contemporary jewelry takes, from simple rings to elaborate body jewelry that blurs the boundaries between art and adornment. 460 color illustrations. 272 pages. in english. $ 35.00 ADORNED – TRADITIONAL JEWELRY AND BODY DECORATION FROM AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC adorned draws on the internationally recognised ethnographic collection of the macleay museum at the university of sidney and the collections of individual members of the oceanic art society of australia. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Ceramics Monthly Mar05 Cei03

www.ceramicsmonthly.org Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 895-4213 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Ren£e Fairchild assistant editor Jennifer Poellot publisher Rich Guerrein Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] (614) 794-5809 fax: (614) 891-8960 [email protected] (614) 794-5866 advertising manager Steve Hecker advertising services Debbie Plummer Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (614) 794-5890 [email protected] marketing manager Susan Enderle Design/Production design Paula John graphics David Houghton Editorial, advertising and circulation offices 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio 43081 USA Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle Dick Lehman Don Pilcher Bernie Pucker Tom Turner Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by The American Ceramic Society, 735 Ceramic Place, Westerville, Ohio 43081; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the editors or The Ameri can Ceramic Society. subscription rates: One year $32, two years $60, three years $86. Add $25 per year for subscriptions outside North America. In Canada, add 7% GST (registration number R123994618). back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus $3 shipping/ handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day air); and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery. change of address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation De partment, PO Box 6136, Westerville, OH 43086-6136. contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are available online at www.ceramicsmonthly.org. -

Oral History Interview with Michael W. Monroe

Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe AAA.monroe18 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe Identifier: AAA.monroe18 Date: 2018 January 22-March 1 Creator: Monroe, Michael W. (Interviewee) Herman, Lloyd E. Extent: 8 Items (sound files (3 hr., 59 min.) Audio; digital, wav) 71 Pages (Transcript) Language: English . Digital Digital Content: Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe, -

At Long Last Love Press Release

At Long Last Love: Fiber Sculpture Gets Its Due October 2014 It looks as if 2014 will be the year that contemporary fiber art finally gets the recognition and respect it deserves. For us, it kicked off at the Whitney Biennial in May which gave pride of place to Sheila Hicks’ massive cascade, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column. Last month saw the opening of the influential Thread Lines, at The Drawing Center in New York featuring work by 16 artists who sew, stitch and weave. Now at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the development of ab- straction and dimensionality in fiber art from the mid-twentieth centu- ry through to the present is examined in Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present from October 1st through January 4, 2015. The exhibition features 50 works by 34 artists, who crisscross generations, nationalities, processes and aesthetics. It is accompanied by an attractive companion volume, Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present available at browngrotta.com. There are some standout works in the exhibition — we were thrilled Fiber: Sculpture 1960 — present opening photo by Tom Grotta to see Naomi Kobayashi’s Ito wa Ito (1980) and Elsi Giauque’s Spatial Element (1989), on loan from European museums, in person after ad- miring them in photographs. Anne Wilson’s Blonde is exceptional and Ritzi Jacobi and Françoise Grossen are represented by strong works, too, White Exotica (1978, created with Peter Jacobi) and Inchworm, respectively. Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present aims to create a sculp- tural dialogue, an art dialogue — not one about craft, ICA Mannion Family Senior Curator Jenelle Porter explained in an opening-night conversation with Glenn Adamson, Director, Museum of Arts and Design. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015" (2015). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 71. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 27. NUMBER 2. FALL, 2015 Cover Image: Collaborative work by Pat Hickman and David Bacharach, Luminaria, 2015, steel, animal membrane, 17” x 23” x 21”, photo by George Potanovic, Jr. page 27 Fall 2015 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Ellyane Hutchinson (Website Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) and Vita Plume (Vice President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives.