Urine Drug Testing: Current Recommendations and Best Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educational Commentary – Testing for Amphetamines and Related Compounds

EDUCATIONAL COMMENTARY – TESTING FOR AMPHETAMINES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this exercise, participants will be able to: • list amphetamine-like compounds that may be detected by immunoassay screening tests for amphetamines. • describe the 3 types of amphetamine immunoassays based on their antibody specificity. • discuss common causes of false-positive results when testing for amphetamines. Correct interpretation of testing results for amphetamines and related compounds is dependent on many factors including an understanding of the nomenclature, structure, and metabolism of these compounds. The class of phenethylamine compounds having varying degrees of sympathomimetic activity include amphetamine, methamphetamine, and many other compounds known by several names including amphetamines (as a group), designer drugs often grouped together as ecstasy [3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA); 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), and 3,4- methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine (MDEA)], and sympathomimetic amines including ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine found in over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Amphetamine, a primary amine, and methamphetamine, a secondary amine, have a stereogenic center and have enantiomers or optical isomers designated d (or +) for dextrorotatory and l (or -) for levorotatory. In general, the d isomers are the more physiologically active compounds, but pharmaceutical preparations may consist of either isomer or a mixture of both isomers. When the mixture contains equal concentrations of the 2 enantiomers, it is known as a racemic mixture. The existence of enantiomers for amphetamines creates analytical and interpretative problems. Immunoassay Screening The primary screening methods for detecting amphetamines are immunoassays. The structural similarity to amphetamine or methamphetamine of the compounds previously mentioned makes it difficult to produce antibodies specific for amphetamine, methamphetamine, or both. -

Drug Formulary Medi-Cal/Healthy Families Drug Formulary • 2014

2014 Drug Formulary Medi-Cal/Healthy Families Drug Formulary • 2014 Medi-Cal/Healthy Families Drug Formulary • 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS MOLINA HEALTHCARE MEDI-CAL/HEALTHY FAMILIES DRUG FORMULARY ....................................................................................4 PRESCRIPTION CLAIMS PROCESSOR .........................................................5 USING THE MOLINA MEDI-CAL/HEALTHY FAMILIES DRUG FORMULARY ....................................................................................6 CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS .........................................................................6 INDIVIDUAL PRESCRIPTIONS ........................................................................6 GENERIC MEDICATIONS .................................................................................7 PRIOR AUTHORIZATION REQUEST PROCEDURE ......................................7 STEP THERAPY PROCEDURE .......................................................................7 PRESCRIPTION QUANTITY .............................................................................7 URGENT AND AFTER-HOURS MEDICATION POLICY ..................................8 TELEPHONE PRESCRIPTIONS.......................................................................8 DRUG FORMULARY .........................................................................................9 Chapter 1 ANALGESICS ..............................................................................9 Chapter 2 ANTIDIABETIC AGENTS ..........................................................12 Chapter -

Customs Tariff - Schedule

CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE 99 - i Chapter 99 SPECIAL CLASSIFICATION PROVISIONS - COMMERCIAL Notes. 1. The provisions of this Chapter are not subject to the rule of specificity in General Interpretative Rule 3 (a). 2. Goods which may be classified under the provisions of Chapter 99, if also eligible for classification under the provisions of Chapter 98, shall be classified in Chapter 98. 3. Goods may be classified under a tariff item in this Chapter and be entitled to the Most-Favoured-Nation Tariff or a preferential tariff rate of customs duty under this Chapter that applies to those goods according to the tariff treatment applicable to their country of origin only after classification under a tariff item in Chapters 1 to 97 has been determined and the conditions of any Chapter 99 provision and any applicable regulations or orders in relation thereto have been met. 4. The words and expressions used in this Chapter have the same meaning as in Chapters 1 to 97. Issued January 1, 2020 99 - 1 CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE Tariff Unit of MFN Applicable SS Description of Goods Item Meas. Tariff Preferential Tariffs 9901.00.00 Articles and materials for use in the manufacture or repair of the Free CCCT, LDCT, GPT, UST, following to be employed in commercial fishing or the commercial MT, MUST, CIAT, CT, harvesting of marine plants: CRT, IT, NT, SLT, PT, COLT, JT, PAT, HNT, Artificial bait; KRT, CEUT, UAT, CPTPT: Free Carapace measures; Cordage, fishing lines (including marlines), rope and twine, of a circumference not exceeding 38 mm; Devices for keeping nets open; Fish hooks; Fishing nets and netting; Jiggers; Line floats; Lobster traps; Lures; Marker buoys of any material excluding wood; Net floats; Scallop drag nets; Spat collectors and collector holders; Swivels. -

Review Memorandum

510(k) SUBSTANTIAL EQUIVALENCE DETERMINATION DECISION SUMMARY ASSAY ONLY TEMPLATE A. 510(k) Number: k062575 B. Purpose for Submission: New device C. Measurand: Amphetamine, Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines, Cocaine, Methamphetamine, Phencyclidine, Methadone, Opiates, THC, and Tricyclic Antidepressants. D. Type of Test: Qualitative immunoassay E. Applicant: Princeton BioMeditech Corporation F. Proprietary and Established Names: AccuSign RC DOA10 (MET/OPI/COC/THC/PCP/BZO/BAR/MTD/TCA/AMP) StatusFirst DOA10 (MET/OPI/COC/THC/PCP/BZO/BAR/MTD/TCA/AMP) G. Regulatory Information: Product Code Classification Regulation Section Panel LAG II 862.3610 91 (Tox) Methamphetamine test system DJG II 862.3650, Enzyme 91 (Tox) Immunoassay, Opiates DIO II 862.3250, Enzyme 91 (Tox) Immunoassay, Cocaine and Cocaine Metabolites 1 Product Code Classification Regulation Section Panel DKE II 862.3870 91 (Tox) Cannabinoid test system LCM Unclassified (510k 862.3100 Enzyme 91 (Tox) required) immunoassay, Phencyclidine DKZ II 862.3100 91 (Tox) Amphetamine test system JXM II 862.3170 Enzyme 91 (Tox) immunoassay, Barbiturate DIS II 862.3150 91 (Tox) Barbiturate test system DJR II 862.3620 91 (Tox) Methadone test system LFI II 862.3910 Tricyclic 91 (Tox) antidepressant drugs test system H. Intended Use: 1. Intended use(s): See indications for use below. 2. Indication(s) for use: Immunoassay for the qualitative detection of methamphetamine, opiates, cocaine metabolite, THC metabolite, phencyclidine, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants, methadone, and amphetamine in human urine to assist in screening of drug of abuse samples. The detecting cut-off concentrations are as follows: MET D-Methamphetamine 1000 ng/mL OPI Morphine 300 ng/mL COC Benzoylecgonine 300 ng/mL THC 11-nor-Δ9-9-carboxylic acid 50 ng/mL PCP Phencyclidine 25 ng/mL Benzodiazepine Oxazepam 300 ng/mL Barbiturate Secobarbital 300 ng/mL Methadone Methadone 300 ng/mL TCA Nortriptyline 1000 ng/mL AMP D-Amphetamine 1000 ng/mL 2 This assay provides only a preliminary analytical test result. -

Acetaminophen, Isometheptene, and Dichloralphenazone

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Acetaminophen, Isometheptene, and Dichloralphenazone This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. Brand Names: US Nodolor [DSC] Warning This drug has acetaminophen in it. Liver problems have happened with the use of acetaminophen. Sometimes, this has led to a liver transplant or death. Most of the time, liver problems happened in people taking more than 4,000 mg (milligrams) of acetaminophen in a day. People were also often taking more than 1 drug that had acetaminophen. Avoid drinking alcohol while taking this drug. What is this drug used for? It is used to treat headaches. Acetaminophen, Isometheptene, and Dichloralphenazone 1/8 What do I need to tell my doctor BEFORE I take this drug? If you have an allergy to acetaminophen, isometheptene, dichloralphenazone, or any other part of this drug. If you are allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell your doctor about the allergy and what signs you had. If you have any of these health problems: Glaucoma, heart disease, high blood pressure, liver disease, or poor kidney function. If you have blood vessel problems, including in the heart or brain. If you have had a recent heart attack or stroke. If you have taken certain drugs for depression or Parkinson’s disease in the last 14 days. This includes isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, selegiline, or rasagiline. Very high blood pressure may happen. -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

PQA Measure Specifications ______

PQA Measure Specifications ______________________________________________________________________________ Table DDI-A: Target Medications and Precipitant Medications Table DDI-A Category Target Drug or Drug Class (Step 1) Precipitant Drug or Drug Class (Step 2) A Benzodiazepines: alprazolam, midazolam, triazolam Azole antifungal agents: ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole B carbamazepine Clarithromycin, erythromycin, telithromycin C cyclosporine Rifamycins: rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine D digoxin clarithromycin, erythromycin, azithromycin, telithromycin E Ergot alkaloids: ergotamine, dihydroergotamine clarithromycin, erythromycin, telithromycin F Estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives: Rifamycins: rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine desogestrel-ethinyl estradiol, drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol, estradiol valerate-dienogest, ethinyl estradiol-ethynodiol, ethinyl estradiol-levonorgestrel, ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone, ethinyl estradiol- norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol-norgestrel, mestranol- norethindrone G MAO Inhibitors: isocarboxazid, linezolid, phenelzine, Sympathomimetics: amphetamines, atomoxetine, rasagiline, selegiline, tranylcypromine, sibutramine benzphetamine, dextroamphetamine, diethylpropion, isometheptene, methamphetamine, methylphenidate, phendimetrazine, phentermine, phenylephrine, pseudoephedrine, tapentadol, dexmethylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine Serotonergic Agents: buspirone, citalopram, cyclobenzaprine, desvenlafaxine, dextromethorphan, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, -

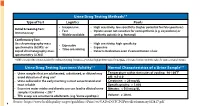

Urine Drug Testing Methods3-5 Urine Drug Testing Specimen Validity3-4

Urine Drug Testing Methods3-5 Type of Test Logistics Pearls • Inexpensive • High sensitivity, low specificity (higher potential for false positives) Initial Screening Test: • Fast • Opiate screen not sensitive for semisynthetic (e.g. oxycodone) or Immunoassay • Widely available synthetic opioids (e.g. fentanyl) Confirmatory Test: Gas chromatography-mass • High sensitivity, high specificity • Expensive spectrometry (GCMS)+ or • Expensive • Time consuming Liquid chromatography-mass • Detects medication even if concentration is low spectrometry (LCMS) + GCMS is considered the criterion standard for confirmatory testing; Immunoassay tests have high predictive values for marijuana and cocaine, but lower predictive values for opiates and amphetamines Urine Drug Testing Specimen Validity3-4 Normal Characteristics of a Urine Sample3-5 • Urine samples that are adulterated, substituted, or diluted may Temperature within 4 minutes of voiding: 90-100⁰F avoid detection of drug use4 pH: 4.5-8.0 • Urine collected in the early morning is most concentrated and Creatinine: > 20 mg/dL most reliable Specific gravity: > 1.003 • Excessive water intake and diuretic use can lead to diluted urine Nitrates: < 500 mcg/dL samples (Creatinine < 20) 3-4 • THC assays are sensitive to adulterants (e.g. Visine eyedrops) Volume: ≥ 30 mL 4 Source: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOTCPGProviderSummary022817.pdf Urine Drug Testing (UDT) Federal Work Place Cut Off Values3-9 Initial Drug Test Level Confirmatory Drug Test Detection Period After Confirmatory -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens. -

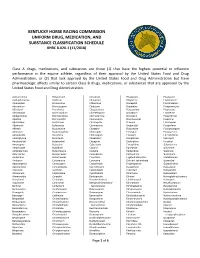

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Tocolytic Therapy a Meta-Analysis and Decision Analysis

Tocolytic Therapy A Meta-Analysis and Decision Analysis David M. Haas, MD, MS, Thomas F. Imperiale, MD, Page R. Kirkpatrick, Robert W. Klein, Terrell W. Zollinger, DrPH, and Alan M. Golichowski, MD, PhD OBJECTIVE: To determine the optimal first-line tocolytic ing prostaglandin inhibitors, only 80 would deliver within agent for treatment of premature labor. 48 hours, compared with 182 for the next-best treatment. METHODS: We performed a quantitative analysis of ran- CONCLUSION: Although all current tocolytic agents domized controlled trials of tocolysis, extracting data on were superior to no treatment at delaying delivery for maternal and neonatal outcomes, and pooling rates for both 48 hours and 7 days, prostaglandin inhibitors were each outcome across trials by treatment. Outcomes were superior to the other agents and may be considered the delay of delivery for 48 hours, 7 days, and until 37 weeks; optimal first-line agent before 32 weeks of gestation to adverse effects causing discontinuation of therapy; absence delay delivery. of respiratory distress syndrome; and neonatal survival. We (Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:585–94) used weighted proportions from a random-effects meta- analysis in a decision model to determine the optimal first-line tocolytic therapy. Sensitivity analysis was per- reterm birth, defined as any birth before the gesta- formed using the standard errors of the weighted propor- Ptional age of 37 weeks, is responsible for most of the 1–3 tions. neonatal morbidity and mortality in the United States and consumes 35% of all U.S. healthcare spending on RESULTS: Fifty-eight studies satisfied the inclusion crite- 4 ria. -

Effects of Ritodrine Hydrochloride, a Beta2-Adrenoceptor Stimulant, on Uterine Motilities in Late Pregnancy

Japan. J. Pharmacol. 35, 319-326 (1984) 319 Effects of Ritodrine Hydrochloride, a Beta2-Adrenoceptor Stimulant, on Uterine Motilities in Late Pregnancy Shigeru IKEDA, Hiroshi TAMAOKI, Masuo AKAHANE and Yoshifumi NEBASHI Central ResearchLaboratories, Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. 19-48 Yoshino,Matsumoto 399-65, Japan Accepted April7, 1984 Abstract•\Ritodrine hydrochloride (ritodrine) is a beta2-adrenoceptor stimulant which has been effectively prescribed for the prevention of premature labor. The present studies were carried out to investigate the effects of ritodrine on uterine motility in rats and rabbits during gestation, as compared with those of isoproterenol and isoxsuprine. The results were as follows: 1) Spontaneous movements and evoked contractile responses of isolated rat uterus (19-20th days of gestation) were suppressed by 10-9-1 0-6 M ritodrine. The potency of ritodrine was approximately 10 times more than that of isoxsuprine and 100-1,000 times less than that of iso- proterenol. 2) When these drugs were administered to pregnant rats or rabbits intravenously, the tocolytic potency was in the following order: isoproterenol> ritodrine>isoxsuprine. 3) Ritodrine induced hypotension and tachycardia, but these effects were less than those of isoproterenol and isoxsuprine. 4) The effects of isoproterenol and ritodrine were almost prevented by pretreatment with pro- pranolol, but those of isoxsuprine were only partially or not affected. These results suggest that ritodrine is effective in preventing the uterine contractions in rats and rabbits and that it has less effect on the circulatory system than isoproterenol and isoxsuprine. It is also concluded that ritodrine produces these effects through activation of beta-adrenoceptors.