"The Music of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach" by David Schulenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Two Flutes

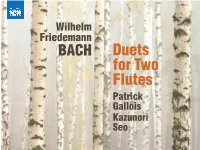

Wilhelm Friedemann BACH Duets for Two Flutes Patrick Gallois Kazunori Seo Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784) Sonatas has been the object of some speculation.1 It has two-part writing, its rapid outer movements framing a C Six Duets for Two Flutes, F.54–59 been suggested that the Duets in E minor, F.54 and G major, minor Adagio. The Duet in F major, F.57, has at its heart a F.59 may be relatively early works, dating from 1729 or D minor Cantabile, the two parts intricately interwoven, with Born in Weimar in 1710, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the Sebastian had abandoned what had been, until his patron’s perhaps from his first years in Dresden. The Duets in E flat a rapid final movement. The demands for virtuosity suggest eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach by his first wife, Maria marriage, a happy position at court for employment under major, F.55 and F major, F.57 may have been written before the influence of distinguished flautists in Dresden, Pierre- Barbara. When his father moved to Cöthen in 1717 as Court the city council in Leipzig, so his son left the court society of 1741, a date suggested by the use made of extracts for his Gabriel Buffardin, the teacher of Quantz, who was employed Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, Dresden for municipal employment in Halle, the birth-place Solfeggi by Quantz, who was then employed by Frederick for many years at the court of the Elector of Saxony and, Wilhelm Friedemann presumably studied at the Lutheran of Handel, who had briefly served as organist there. -

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach COMPLETE ORGAN MUSIC Filippo Turri Wilhelm Friedemann Bach 1710-1784 The first son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Complete Organ Music Bach (Weimar, 22 November 1710 – Berlin, 1 July 1784) lived a life that in many respects would fit in perfectly with the biography of a tormented artist of the Drei dreistimmigen Fugen Sieben Choralvorspiele F.38 romantic age. He studied under his father, showing early talent as an instrumentalist Three 3-part Fugues Seven Chorale Preludes F.38 (organist, harpsichordist, violinist) and composer, as well as considerable gifts as 1. Fugue in B flat F.34 2’56 15. I. Nun komm der a mathematician. Given his father’s Pythagorean passions, this latter aptitude is 2. Fugue in F F.33 5’22 Heiden Heiland 1’46 not really as surprising at it might at first seem, yet it is certainly true that Wilhelm 3. Fugue in C minor F.32 6’38 16. II. Christe, der du bist Tag Friedemann was versatile and his interests widespread. At the early age of 23 he was und Licht 2’15 appointed principal organist at the church of St. Sophia in Dresden, and in 1747 Acht dreistimmigen Fugen für Orgel 17. III. Jesu, meine Freude 3’59 became Musikdirektor and organist at the Church of Our Lady in Halle. On account oder Clavier F.31 18. IV. Durch Adams Fall is of his years in Halle, where he married Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi (1721-1791), he is Eight 3-part fugues for Organ ganz verderbt 3’35 often referred to as the “Halle” Bach. -

Editorial Guidelines

CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH he omplete orks Editorial Guidelines The Packard Humanities Institute Cambridge, Massachusetts 2019 Editorial Board Robert D. Levin, Chair Darrell M. Berg, General Editor, Series I Ulrich Leisinger, General Editor, Series IV, V, VI Peter Wollny, General Editor, Series II, III, VII Walter B. Hewlett John B. Howard David W. Packard Uwe Wolf Christoph Wolff † Christopher Hogwood, chair 1999–2014 Editorial Office Paul Corneilson, Managing Editor [email protected] Laura Buch, Editor [email protected] Jason B. Grant, Editor [email protected] M a rk W. K n o l l , Editor [email protected] Lisa DeSiro, Production and Editorial Assistant [email protected] Ruth B. Libbey, Administrator and Editorial Assistant [email protected] 11a Mt. Auburn Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Phone: (617) 876-1310 Fax: (617) 876-0074 Website: www.cpebach.org Updated 2019 Contents Introduction to and Organization of the Edition. 1 A. Prefatory Material. 5 Title Pages . 5 Part Titles . 5 Table of Contents . 5 Order of Pieces . 6 Alternate Versions . 7 Abbreviations . 7 General Preface . 8 Preface to Genres . 8 Introduction . 8 Tables . 8 Facsimile Plates and Illustrations . 9 Captions . 9 Original Dedications and Prefaces . 9 Texts of Vocal Works . 9 B. Style and Terminology in Prose . 10 Titles of Works . 10 Movement Designations . 11 Thematic Catalogues. 11 Geographical Names . 12 Library Names and RISM Sigla . 12 Name Authority. 12 Categories of Works . 13 Varieties of Works . 13 Principal and Secondary Churches of Hamburg . 14 Liturgical Calendar . 14 Keys . 15 Pitch Names and Music Symbols . 15 Dynamics and Terms. 16 Meters and Tempos . -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

The Family Bach November 2016

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra Jane Glover, Music Director Violin 1 Flute Gina DiBello, Mary Stolper, principal concertmaster Alyce Johnson Kevin Case, assistant Oboe concertmaster Jennet Ingle, principal Kathleen Brauer, Peggy Michel assistant concertmaster Bassoon Teresa Fream William Buchman, Michael Shelton principal Paul Vanderwerf Horn Violin 2 Samuel Hamzem, Sharon Polifrone, principal principal Fritz Foss Ann Palen Rika Seko Harpsichord Paul Zafer Stephen Alltop François Henkins Viola Elizabeth Hagen, principal Terri Van Valkinburgh Claudia Lasareff- Mironoff Benton Wedge Cello Barbara Haffner, principal Judy Stone Mark Brandfonbrener Bass Collins Trier, principal Andrew Anderson Performing parts based on the critical edition Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Complete Works (www.cpebach.org) were made available by the publisher, the Packard Humanities Institute of Los Altos, California. The Family Bach Jane Glover, conductor Sunday, November 20, 2016, 7:30 PM North Shore Center for the Performing Arts, Skokie Tuesday, November 22, 2016, 7:30 PM Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago Gina DiBello, violin Mary Stolper, flute Sinfonia from Cantata No. 42 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Adagio and Fugue for 2 Flutes Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Strings in D Minor (1710-1784) Adagio Allegro Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major J. S. Bach Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Gina DiBello, violin INTERMISSION Flute Concerto in B-flat Major Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) Allegretto Adagio Allegro assai Mary Stolper, flute Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) Allegro Andante più tosto Adagio Allegro molto Biographies Acclaimed British conductor Jane Glover has been Music of the Baroque’s music director since 2002. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Bach́s Family Choral Motets Kammerchor Stuttgart FRIEDER BERNIUS HC18014.Booklet.Chorales.Qxp PH????? Booklet Gamben/Handel 20.03.19 15:24 Seite 2

HC18014.Booklet.Chorales.qxp_PH?????_Booklet_Gamben/Handel 20.03.19 15:24 Seite 1 Johann Christoph ALTNICKOL Johann Christoph Friedrich BACH Bach́s Family Choral Motets Kammerchor Stuttgart FRIEDER BERNIUS HC18014.Booklet.Chorales.qxp_PH?????_Booklet_Gamben/Handel 20.03.19 15:24 Seite 2 Bachs Familie · Choral‐Motetten DEUTSCH Kein Komponist der Musikgeschichte hat „seines Vaters Claviercompositionen am so viele hochbegabte Schüler hervor ge- fertigsten vorgetragen“ habe. Anfang bracht wie Johann Sebastian Bach. Da er Januar 1750 erhielt er auf dessen Em- etliche von ihnen in seiner Wohnung pfehlung eine Anstellung als Kammermu- beherbergte, konnten sie tiefe Einblicke in siker am Hofe des Grafen Wilhelm von sein Schaffen gewinnen. Unter seinen Schaumburg-Lippe in Bückeburg, einem komponierenden Söhnen stand Johann der Aufklärung verpflichteten, sozial enga- Christoph Friedrich, der sogenannte „Bücke- gierten, charismatischen Adligen, dessen burger Bach“, am wenigsten im Rampen- Neigungen viel eher den schönen Künsten licht der Öffentlichkeit. Als „Externus“ be- als höfischem Repräsentationsbedürfnis suchte der zweitjüngste Sohn zunächst die galten. Mitunter dirigierte er die Kapelle Thomasschule, erhielt musikalischen Unter- seiner Residenz selbst. Seine Gattin ließ richt vom Vater und wurde darüber hinaus sich von Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach durch seinen entfernten Meininger Cousin unterrichten und beschenkte ihn reichlich. Johann Elias Bach in außermusikalischen Dessen Jahresgehalt belief sich zeitweise Fächern unterwiesen. An der Leipziger auf stolze 1.000 Reichstaler. Er blieb – ab- Universität immatrikulierte er sich für das gesehen von einer Reise nach London zum Fach der Jurisprudenz, doch brach er sein jüngeren Bruder Johann Christian – Zeit Studium schon vorzeitig wieder ab. Bereits seines Lebens in Bückeburg. Dort heiratete seit Mitte der 1740er Jahre zählte er zu er die Sopranistin Lucia Münchhausen. -

The Keyboard Music of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Updates and Corrections

The Keyboard Music of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Updates and Corrections Chapter 1 “But any biography of these composers must remain incomplete in ways that is not the case for musicians whose inner life, emotional as well as musical, is better documented . .” (p. 5). Friedemann’s inner life has nevertheless been reconstructed fictionally in the novels, films, and operas mentioned on pages 12–13. To these must be added Lauren Belfer’s 2016 novel And After the Fire, which, although continuing the tradition begun by Brachvogel of making Friedemann a lover of certain wealthy young women, in other respects paints plausible pictures of both the aging composer and his youthful pupil Sara Levy. “One long-standing enigma . his fourth cousin” (p. 11) The exact relationship of Friedemann to J. C. Bach of Halle is less certain and probably more remote than is indicated here. The “Halle Clavier Bach” was descended from Lips (Philippus) Bach, who might have been a brother or son of Veit Bach (Friedemann’s great-great-great-grandfather). All that can be said assuredly is that the two probably were distantly related, with one or more common ancestors, but none within five generations as suggested here. J. C. Bach of Halle belonged to the same Meiningen branch of the family that also produced the composer Johann Ludwig (his uncle) and the painters Gottlieb Friedrich and Samuel Anton Bach (his cousins). Chapter 2 “I do not give instruction” (see p. 292n. 27) The claim that Friedemann did not teach during his Berlin years is based not only on Friedemann’s own declaration but on a 1779 letter of Kirnberger to Forkel (in Bitter, 2:323: “auch Lection geben mag er nicht”). -

Zum Umfang Des Erhaltenen Orgelwerks Von Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Pieter Dirksen Zum Umfang des erhaltenen Orgelwerks von Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Es gibt verschiedene Beschreibungen über das Orgelspiel Wilhelm Friedemann Bachs, ganz im Gegensatz zu der äußerst mageren diesbezüglichen Berichterstattung über das Spiel seines Vaters. Obwohl dies ohne Zweifel mit dem starken Aufkommen der deut- schen Musikkritik in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts in Beziehung steht, klingt doch klar das Erstaunen über die hohe Orgelkunst des ältesten Bach-Sohns durch. Zum Beispiel schreibt Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart: Er hat seinen Vater im Orgelspiel erreicht, wo nicht übertroffen. Er besitzt ein sehr feuriges Genie, eine schöpferische Einbildungskraft, Originalität und Neuheit der Gedanken, eine stürmende Geschwindigkeit und die magische Kraft, alle Herzen mit seinem Orgelspiel zu bezaubern. Der Natur der Orgel hat er sich ganz bemächtiget; sein Registerverständnis hat ihm noch niemand nachgemacht. Er mischt die Register, ohne sein Spiel nur einen Augenblick zu unterbrechen – wie der Maler seine Farben auf der Palette, und bringt dadurch ein bewundernswürdiges Ganzes hervor. Seine Faust [Hand] ist eine Riesenfaust, die durch tagelanges Spielen nicht ermattet. Con- trapunkt, Ligaturen, neue ungewöhnliche Ausweichungen, herrliche Harmonien und äusserst schwere Sätze, die er mit der grössten Reinheit und Richtigkeit herausbringt, herzerhebendes Pathos, und himmlische Anmut – all dies vereinigt Zauberer Bach in sich und erregt dadurch das Erstaunen der Welt.1 Von besonderem Interesse für unser Thema ist Schubarts -

The Bach Family There Has Never Been a Dynasty Like It! We Have

The Bach Family There has never been a dynasty like it! We have Johann Sebastian Bach to thank for much of the Genealogy as well. In the region of Thuringia, the name of Bach was synonymous with music, but they were also a 'family' experiencing the ups and downs of 17th & 18th century life, from happy marriages and joyful family music-making in this devoutly Lutheran community to coping with infant mortality and dysfunctional behaviour. The Bach Family encountered the lot. In this page, we visit the lives of key members of this remarkable family, a family that was humble in its intent, served the community, were appropriately deferential to their various patrons or princes, and whose music lives on through our performances today. Joh. Seb. Bach's ancestors set the tone and musical direction, but this particular family member raised the bar higher in scale and invention. Sebastian taught his own sons too, plus many of the offspring of his relatives. His eldest sons Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel certainly held their Father in high regard, but also wanted to plough their own furrow - not easy even then. Others either held church or court positions and one travelled first to Italy and then to Georgian London in order to ply his trade - Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son. The family's ancestry goes back to the late 16th/early 17th centuries to a certain Vitus (Veit) Bach (d.1619) who left his native Hungary and came to live in Wechmar, near Gotha in Thuringia. He was a baker by trade. -

The Flute Duets of WF Bach

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1992 The Flute Duets of W.F. Bach: Sources And Dating Anita Breckbill University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Breckbill, Anita, "The Flute Duets of W.F. Bach: Sources And Dating" (1992). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 178. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/178 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in FLUTING AND DANCING: ARTICLES AND REMINISCENCES FOR BETTY BANG MATHER ON HER 65TH BIRTHDAY, ed. David Lasocki (New York: McGinnis & Marx, 1992). Copyright (c) 1992 McGinnis & Marx; used by permission. THE FLUTE DUETS OF W.F. BACH: SOURCES AND DATING Anita Breckbill The six flute duets of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784) are among the finest examples of this genre from the eighteenth century. That they are still not as well known as they deserve to be may stem partly from the problems with the editions that have been available until recently.' The question of when these duets were composed has never been completely answered, largely because the sources present a confusing picture. In his classic biography of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1913), Martin Falck remarked that Bach is known to have com- posed pieces for the flute in Berlin (or, in other words, during the last decade of his life) but it was not known whether the duets belonged to those pieces.2 From a consideration of the autograph manuscripts he did conclude that one of the duets was composed in Berlin and that another was presumably also composed there.