Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach wrote the two keyboard con- composed the concertos for performance by or with the certos contained in the present volume—the Concerto princess’s musical establishment, or she herself may have in G Major, Wq 34 and the Concerto in E-flat Major, commissioned them directly from Bach. There is, however, Wq 35—in 1755 and 1759, respectively. They are listed on no explicit evidence that confirms this supposition. Bach pages 32–33 in NV 1790: subsequently adapted both works for harpsichord for his No. 35. G. dur. B. 1755. Orgel oder Clavier, 2 Violinen, own use and also arranged the G-major concerto for flute 4 Bratsche und Baß; ist auch für die Flöte gesetzt. (Wq 169). Neither work was published in Bach’s lifetime. No. 36. Es. dur. B. 1759. Orgel oder Clavier, 2 Hörner, The source record for both Wq 34 and 35 is good. Au- 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Baß. tograph or partly autograph scores and parts survive for both works. These indicate that Bach made alterations and Except for the Concerto in E-flat Major for Harpsichord improvements at a somewhat later time after the works and Fortepiano, Wq 47, these two concertos are the only were composed. In addition, more than a dozen contem- keyboard concertos for which a keyboard instrument porary copies of each work exist, indicating that they were other than the harpsichord is noted in NV 1790. The fact both well-known and popular with the North German that the organ is listed before the harpsichord in the de- musical public. -

For Two Flutes

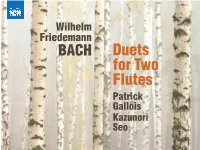

Wilhelm Friedemann BACH Duets for Two Flutes Patrick Gallois Kazunori Seo Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784) Sonatas has been the object of some speculation.1 It has two-part writing, its rapid outer movements framing a C Six Duets for Two Flutes, F.54–59 been suggested that the Duets in E minor, F.54 and G major, minor Adagio. The Duet in F major, F.57, has at its heart a F.59 may be relatively early works, dating from 1729 or D minor Cantabile, the two parts intricately interwoven, with Born in Weimar in 1710, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the Sebastian had abandoned what had been, until his patron’s perhaps from his first years in Dresden. The Duets in E flat a rapid final movement. The demands for virtuosity suggest eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach by his first wife, Maria marriage, a happy position at court for employment under major, F.55 and F major, F.57 may have been written before the influence of distinguished flautists in Dresden, Pierre- Barbara. When his father moved to Cöthen in 1717 as Court the city council in Leipzig, so his son left the court society of 1741, a date suggested by the use made of extracts for his Gabriel Buffardin, the teacher of Quantz, who was employed Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, Dresden for municipal employment in Halle, the birth-place Solfeggi by Quantz, who was then employed by Frederick for many years at the court of the Elector of Saxony and, Wilhelm Friedemann presumably studied at the Lutheran of Handel, who had briefly served as organist there. -

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Matt Machemer

GRADUATE ORGAN RECITAL Matthew A. Machemer In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Church Music June 25, 2021 7:00 P.M. Chapel of Christ Triumphant Concordia University Wisconsin Praeludium in G Nicolaus Bruhns 1665 – 1697 While Nicolaus Bruhns was not blessed with a long life, he was gifted with incredible musical abilities and a keen compositional sense. He was both a gifted violinist and viola de gamba player as well as an acclaimed organist. By his mid-twenties, Bruhns had studied with some of the most celebrated musicians of his time, most notably Dietrich Buxtehude, who was particularly fond of the young musician and whose influence can be seen in Bruhn’s own compositions. One such example is Bruhns’ Praeludium in G: an excellent example of the Stylus Phantasticus made famous under by Buxtehude himself. The Praeludium in G is perhaps Bruhns’ most structurally significant work. The praeludium is ordered according to the common five-part structure indicative of most north German organ praeludia of the time. The piece opens with a virtuosic fanfare section, interspersing manual and pedal flourishes with more structured motivic material. This motivic material forms the basis of the first fugal section, which features six voices: four in the manuals and two in the pedals. One can imagine young Nicolaus, who was known to play the violin and the organ pedals simultaneously, delighting in this masterful display. A middle improvisatory section follows featuring pedal solos and manual figurations reminiscent of a fiery violin solo. The fourth section is the final fugue, which closely mirrors the first, though the subject is presented in a different time signature and features only five voices instead of six. -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach COMPLETE ORGAN MUSIC Filippo Turri Wilhelm Friedemann Bach 1710-1784 The first son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Complete Organ Music Bach (Weimar, 22 November 1710 – Berlin, 1 July 1784) lived a life that in many respects would fit in perfectly with the biography of a tormented artist of the Drei dreistimmigen Fugen Sieben Choralvorspiele F.38 romantic age. He studied under his father, showing early talent as an instrumentalist Three 3-part Fugues Seven Chorale Preludes F.38 (organist, harpsichordist, violinist) and composer, as well as considerable gifts as 1. Fugue in B flat F.34 2’56 15. I. Nun komm der a mathematician. Given his father’s Pythagorean passions, this latter aptitude is 2. Fugue in F F.33 5’22 Heiden Heiland 1’46 not really as surprising at it might at first seem, yet it is certainly true that Wilhelm 3. Fugue in C minor F.32 6’38 16. II. Christe, der du bist Tag Friedemann was versatile and his interests widespread. At the early age of 23 he was und Licht 2’15 appointed principal organist at the church of St. Sophia in Dresden, and in 1747 Acht dreistimmigen Fugen für Orgel 17. III. Jesu, meine Freude 3’59 became Musikdirektor and organist at the Church of Our Lady in Halle. On account oder Clavier F.31 18. IV. Durch Adams Fall is of his years in Halle, where he married Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi (1721-1791), he is Eight 3-part fugues for Organ ganz verderbt 3’35 often referred to as the “Halle” Bach. -

Fugal Procedures in the Mendelssohn Organ Sonatas

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY CQ tio.ssi COLLEGE COLLECTION Gift of Charlotte Alston ALSTON, CHARLOTTE LENORA. Fugal Procedures in the Mendelssohn Organ Sonatas. (1968) Directed by: Mr. Jack Jarrett. pp. 54 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) wrote Six Sonatas for Organ, Opus 65, published in 1845. Fugal procedures are a predominant feature in these sonatas. With the exception of two independent fugues, the Mendelssohn sonatas represent an instance in com- position where monothematic-form techniques and multi-thematic form techniques are used within the same movement. An examination of the Mendelssohn sonatas was made in an attempt to discover how Mendelssohn uses fugal procedures in multi-thematic forms. The study reveals that Mendelssohn uses fugal procedures within the context of sonata-allegro form and ternary form. The use of fugal procedures within the sonata- allegro form is represented in the first movement of the First Sonata. Its use in the ternary form is found in the first move- ment of the Third Sonata and the first and fourth movements of the Fourth Sonata. The study reveals that the first movement of the First Sonata is a modified fugue in sonata-allegro form. This relation- ship of fugal procedures and sonata-allegro form poses a funda- mental problem of fugal continuity. Accordingly, cadences play an important role in this movement. The basic outline of the tonal structure of the movement was found to be that of sonata- allegro form. The type of punctuation normally associated with sonata-allegro form is modified to allow for fugal continuity. -

Rhythmic Freedom in Mendelssohn's Six Organ Sonatas

Rhythmic Freedom in Mendelssohn's Six Organ Sonatas Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Thomas , William Kullen Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 07:16:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642104 RHYTHMIC FREEDOM IN MENDELSSOHN’S SIX ORGAN SONATAS by William Kullen Thomas _____________________________ Copyright ©William Kullen Thomas 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by William Kullen Thomas, titled Rhythmic Freedom in Mendelssohn’s Six Organ Sonatas and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ___ ____________________________________ Date: June 15, 2020 Professor Rex A. Woods ___ ______________________________________ Date: June 15, 2020 Dr. Jay Rosenblatt Date: June 15, 2020 Professor Edward Reid Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

The Cradle of the Reformation Lutherstadt Wittenberg

Dear Travel Writer, Imagine seeing them with your own two eyes, touching them with your own two hands: The great bronze doors of Lutherstadt Wittenberg’s Castle Church, marking the very spot where Martin Luther posted the ninety-five theses that changed the world. Picture exploring the church in which the Great Reformer was baptized or stepping inside the tiny room where Luther translated the New Testament in just 10 weeks. Luckily, these unforgettable experiences don’t have to remain the stuff of dreams! Come and explore LutherCountry, the beautiful region in the heart of Germany that invites you to walk in Luther’s footsteps! Find out more on our website; then come visit! LutherCountry: The Cradle of the Reformation Although Martin Luther lived 500 years ago, his presence is still tangible today. Here in LutherCountry, visitors of all ages get the chance to discover myriad original locations that still boast the Great Reformer’s indelible mark – and all within easy reach of each other. Come discover the places where Luther once lived, taught and, preached! In addition to authentic locations that played a major role in Luther’s life, LutherCountry is also home to hundreds of other cultural and historical treasures, with many famous personalities in art and music having left their mark on the region’s cultural landscape. Great composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Frederic Handel, two of the world’s most famous baroque composers, were both born in LutherCountry. And thanks to the great German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder, we now know what Martin Luther actually looked like. -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

Johann Sebastian Bach Johann Sebastian Bach

Southeast Circuit Reformation Update: Week Forty Three Southeast Circuit Reformation Update: Week Forty Three Johann Sebastian Bach Johann Sebastian Bach Rev. Sean Daenzer Rev. Sean Daenzer Johann Sebastian Bach is recognized the world over as a genius Johann Sebastian Bach is recognized the world over as a genius and one of the greatest composers of all time. He was also a de- and one of the greatest composers of all time. He was also a de- vout and orthodox Lutheran. vout and orthodox Lutheran. Bach was born in Eisenach (Luther’s school town and home to Bach was born in Eisenach (Luther’s school town and home to the Wartburg Castle) in 1685 into the Wartburg Castle) in 1685 into a musical family. He was first a a musical family. He was first a violinist, but became intensely violinist, but became intensely interested in music and espe- interested in music and espe- cially the keyboard after the cially the keyboard after the death of his mother while he death of his mother while he was living with His brother, Jo- was living with His brother, Jo- hann Christoph. Bach’s early hann Christoph. Bach’s early schooling was exceptional in the schooling was exceptional in the Lutheran school at Lüneburg, Lutheran school at Lüneburg, where he sang Latin and Ger- where he sang Latin and Ger- man as a choir boy and studied man as a choir boy and studied harpsichord, organ, and com- harpsichord, organ, and com- position. position. In 1703 he was appointed a In 1703 he was appointed a court musician for the Duke of court musician for the Duke of Weimar and also became or- Weimar and also became or- ganist at the New Church in ganist at the New Church in Arndstadt.