Rhythmic Freedom in Mendelssohn's Six Organ Sonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach wrote the two keyboard con- composed the concertos for performance by or with the certos contained in the present volume—the Concerto princess’s musical establishment, or she herself may have in G Major, Wq 34 and the Concerto in E-flat Major, commissioned them directly from Bach. There is, however, Wq 35—in 1755 and 1759, respectively. They are listed on no explicit evidence that confirms this supposition. Bach pages 32–33 in NV 1790: subsequently adapted both works for harpsichord for his No. 35. G. dur. B. 1755. Orgel oder Clavier, 2 Violinen, own use and also arranged the G-major concerto for flute 4 Bratsche und Baß; ist auch für die Flöte gesetzt. (Wq 169). Neither work was published in Bach’s lifetime. No. 36. Es. dur. B. 1759. Orgel oder Clavier, 2 Hörner, The source record for both Wq 34 and 35 is good. Au- 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Baß. tograph or partly autograph scores and parts survive for both works. These indicate that Bach made alterations and Except for the Concerto in E-flat Major for Harpsichord improvements at a somewhat later time after the works and Fortepiano, Wq 47, these two concertos are the only were composed. In addition, more than a dozen contem- keyboard concertos for which a keyboard instrument porary copies of each work exist, indicating that they were other than the harpsichord is noted in NV 1790. The fact both well-known and popular with the North German that the organ is listed before the harpsichord in the de- musical public. -

Matt Machemer

GRADUATE ORGAN RECITAL Matthew A. Machemer In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Church Music June 25, 2021 7:00 P.M. Chapel of Christ Triumphant Concordia University Wisconsin Praeludium in G Nicolaus Bruhns 1665 – 1697 While Nicolaus Bruhns was not blessed with a long life, he was gifted with incredible musical abilities and a keen compositional sense. He was both a gifted violinist and viola de gamba player as well as an acclaimed organist. By his mid-twenties, Bruhns had studied with some of the most celebrated musicians of his time, most notably Dietrich Buxtehude, who was particularly fond of the young musician and whose influence can be seen in Bruhn’s own compositions. One such example is Bruhns’ Praeludium in G: an excellent example of the Stylus Phantasticus made famous under by Buxtehude himself. The Praeludium in G is perhaps Bruhns’ most structurally significant work. The praeludium is ordered according to the common five-part structure indicative of most north German organ praeludia of the time. The piece opens with a virtuosic fanfare section, interspersing manual and pedal flourishes with more structured motivic material. This motivic material forms the basis of the first fugal section, which features six voices: four in the manuals and two in the pedals. One can imagine young Nicolaus, who was known to play the violin and the organ pedals simultaneously, delighting in this masterful display. A middle improvisatory section follows featuring pedal solos and manual figurations reminiscent of a fiery violin solo. The fourth section is the final fugue, which closely mirrors the first, though the subject is presented in a different time signature and features only five voices instead of six. -

Fugal Procedures in the Mendelssohn Organ Sonatas

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY CQ tio.ssi COLLEGE COLLECTION Gift of Charlotte Alston ALSTON, CHARLOTTE LENORA. Fugal Procedures in the Mendelssohn Organ Sonatas. (1968) Directed by: Mr. Jack Jarrett. pp. 54 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) wrote Six Sonatas for Organ, Opus 65, published in 1845. Fugal procedures are a predominant feature in these sonatas. With the exception of two independent fugues, the Mendelssohn sonatas represent an instance in com- position where monothematic-form techniques and multi-thematic form techniques are used within the same movement. An examination of the Mendelssohn sonatas was made in an attempt to discover how Mendelssohn uses fugal procedures in multi-thematic forms. The study reveals that Mendelssohn uses fugal procedures within the context of sonata-allegro form and ternary form. The use of fugal procedures within the sonata- allegro form is represented in the first movement of the First Sonata. Its use in the ternary form is found in the first move- ment of the Third Sonata and the first and fourth movements of the Fourth Sonata. The study reveals that the first movement of the First Sonata is a modified fugue in sonata-allegro form. This relation- ship of fugal procedures and sonata-allegro form poses a funda- mental problem of fugal continuity. Accordingly, cadences play an important role in this movement. The basic outline of the tonal structure of the movement was found to be that of sonata- allegro form. The type of punctuation normally associated with sonata-allegro form is modified to allow for fugal continuity. -

Schübler and Leipzig Chorales Canonic Variations Kåre Nordstoga Schnitger Organ St

BACH SCHÜBLER AND LEIPZIG CHORALES CANONIC VARIATIONS KÅRE NORDSTOGA SCHNITGER ORGAN ST. MARTIN’S CHURCH OF GRONINGEN BACH ORGAN WORKS ‡ ‡ DA BACH VILLE OPPSUMMERE Mot slutten av sitt virke hadde blir demonstrert og uttømt med Bach-eleven Lorenz Mizler, og Den overlegne beherskelsen av Samlingen «Orgelbüchlein» med utsmykket melodi som en vug- J.S. Bach bedre tid enn i de en uovertruffen kunstferdighet. medlemslisten omfattet allerede kanonteknikken er beslektet med korte koralbearbeidelser fra gende sarabande. første årene i Leipzig fra 1723. Telemann og Händel. matematiske løsninger. Det er Weimar får i dette Leipzig-verket Han hadde bygget opp et re- EINIGE CANONISCHE hevdet at hvis ikke Bach hadde en avansert parallell. Teknikker 3. An Wasserflüssen Babylon, pertoar innen mange genrer han De musikalske bidragene skulle blitt musiker, hadde han kanskje fra tysk tradisjon (Pachelbel og BWV 653 VERÄNDERUNGEN ÜBER DAS kunne gripe tilbake til, ikke minst ha vitenskapelig kvalitet, men vært matematiker på høyeste nivå. Buxtehude) finslipes og bringes biblioteket av kantater til sønda- WEYNACHT-LIED «VOM HIMMEL ikke som «en unyttig teori». De Det kan også være en opplevelse opp til nye dimensjoner. Den tyske salmeteksten bygger gens gudstjenester. HOCH, DA KOMM ICH HER» skulle «vekke eller tilfredsstille å studere de skrevne notene med på jødenes klagesang ved Baby- PER CANONES Á 2 CLAVIERS ET menneskers lidenskap». sin kunstferdige kontrapunktikk. Manuskriptet åpner med boksta- lons floder i Salme 137. På norsk Den kortsiktige arbeidsinnsatsen Det er ikke bare «øremusikk», men vene «J.J.», «Jesu juva»: «Hjelp, (og også på tysk) er koralen PÉDALE, BWV 769 med nye verker fra uke til uke Sammen med sitt portrett, det også «øyemusikk»! Jesus». -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

NACH BACH (1750-1850) GERMAN GRADED ORGAN REPERTOIRE by Dr

NACH BACH (1750-1850) GERMAN GRADED ORGAN REPERTOIRE By Dr. Shelly Moorman-Stahlman [email protected]; copyright Feb. 2007 LEVEL ONE Bach, Carl Phillip Emmanuel Leichte Spielstücke für Klavier This collection is one of most accessible collections for young keyboardists at late elementary or early intermediate level Bach, Wilhelm Friedermann Leichte Spielstücke für Klavier Mozart, Leopold Notenbuch für Nannerl Includes instructional pieces by anonymous composers of the period as well as early pieces by Wolfgang Amadeus Merkel, Gustav Examples and Verses for finger substitution and repeated notes WL Schneider, Johann Christian Friderich Examples including finger substitution included in: WL Türk, Daniel Gottlob (1750-1813) Sixty Pieces for Aspiring Players, Book II Based on Türk’s instructional manual, 120 Handstücke für angehende Klavierspieler, Books I and II, published in 1792 and 1795 Three voice manual pieces (listed in order of difficulty) Bach, C.P.E. Prelude in E Minor TCO, I Kittel, Johann Christian TCO, I Prelude in A Major Vierling, Johann Gottfried OMM V Short Prelude in C Minor Litzau, Johannes Barend Short Prelude in E Minor OMM V Four Short Preludes OMM III 1 Töpfer, Johann Gottlob OB I Komm Gott, Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist (stepwise motion) Kittel, Johann Christian Prelude in A Major OMM IV Fischer, Michael Gotthardt LO III Piu Allegro (dotted rhythms and held voices) Four voice manual pieces Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg Prelude in G Minor OMM, I Gebhardi, Ludwig Ernst Prelude in D Minor OMM, I Korner, Gotthilf Wilhelm LO I -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

CC 8805 Engl.Indd

1 Commentary Abbreviations and Sigla To proclaim this date as terminus post quem for the conception of the sonata collection a.c. ante correcturam including the revision of the two named movements appears to be premature in light P Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung, Mus. Ms. of the possibility that Bach did not intend to make the sonatas available to his students Bach (shelf number for scores) for copying. It is unlikely that Bach left Vogler a three-part organ work for copying at the Ped Pedal system end of 1729 (BWV 545 with BWV 529/2) when at this point the second movement had St Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung, Mus. Ms. already found its defi nitive designation as the middle movement of the fi fth sonata. A Bach (shelf number for parts) date of around 1731 thus stands out. The time signature 2| in BWV 526/3, seldom-used by Bach, also points to 1731.3 Perhaps the origin of the sonata collection stands in di- In the individual notes, voices are indicated by Roman numerals for the system and, if rect connection with Bach’s appearance as organist in Dresden in September 1731;4 an necessary, Arabic numerals for the individual voices within the system, each in increas- organ concert in the Dresden Sophienkirche on September 14 is evidence.5 ing order (I 2 = fi rst system, second voice). These designations pertain to the notation of the present edition. Origin of the Primary Source Unless otherwise noted, the individual notes are concerned with differences between Although P 271 is a pure copy, corrections and small modifi cations common to Bach the respective primary source and the notation of the present edition. -

The Musical Compositions for Unaccompanied Solo Tuba by Four

THE MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR UNACCOMPANIED SOLO TUBA BY FOUR AMERICAN PERFORMER-COMPOSERS by DAVID MCLEMORE (Under the Direction of DAVID ZERKEL) ABSTRACT The solo repertoire for tuba is characterized by its small size and lack of stylistic diversity. As with other instruments in Western Art music, a solution to this dearth of repertoire has involved the worked of performer-composers, virtuoso instrumentalists who have created new works for their instrument. This study examines the solo tuba compositions of four American performer-composers: Mike Forbes, Grant Harville, Benjamin Miles, and John Stevens. Each composer’s compositional style and approach is discussed, followed by a musical analysis of their music for tuba alone. As some of these compositions are already staples in the solo tuba repertoire, this study provides a resource to performers and teachers who will perform, study, or teach these compositions. Furthermore, composers and other performer-composers will benefit from the analysis of each performer-composer’s musical style. INDEX WORDS: Mike Forbes, Grant Harville, Benjamin Miles, John Stevens, Music, Tuba, Unaccompanied, Solo, Composer, Performer-Composer THE MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR UNNACOMPANIED SOLO TUBA BY FOUR AMERICAN PERFORMER-COMPOSERS by DAVID MCLEMORE BM, University of Southern California, 2009 MM, University of Michigan, 2011 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 David McLemore All Rights Reserved THE MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR UNACCOMPANIED SOLO TUBA BY FOUR AMERICAN PERFORMER-COMPOSERS by DAVID MCLEMORE Approved: Major Professor: DAVID ZERKEL Committee: ADRIAN CHILDS JEAN MARTIN-WILLIAMS Electronic Version Approved: Julie Coffield Interim Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF EXAMPLES .................................................................................................................. -

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH the Complete Organ Works, Vol

1 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH The Complete Organ Works, Vol. 8 DAVID GOODE Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge Toccata and Fugue, BWV 538 “Dorian” Concerto after Vivaldi Op.3 No. 8, BWV 593 1 I. Toccata 0 I. [Allegro] 2 II. Fugue q II. Adagio w III. Allegro 3 O Lamm Gottes unschuldig 4 Jesus, meine Zuversicht, BWV 728 e Ach Gott und Herr, BWV 714 r Valet will ich dir geben, BWV 736 Trio sonata No. 4, BWV 528 5 I. Adagio - Vivace t Trio in G BWV 1027a 6 II. Andante 7 III. Un poc’allegro Prelude and Fugue, BWV 548 “Wedge” y I. Prelude 8 Prelude, BWV 568 u II. Fugue 9 Fugue in F (BWV anh. 42) 2 BACH, BEAUTY AND BELIEF of St Blasius’s in Mühlhausen (1707 – 1708), court organist THE ORGAN WORKS OF J.S. BACH and chamber musician at Weimar (1708 – 1717), capellmeister at Cöthen (1717 – 1723) and cantor at St Thomas’ Church in Introduction – Bach and the Organ Leipzig (1723 – 1750). The organ loomed large from early on in Bach’s life. The foundations of his multifaceted career as a professional ‘The Complete Organ Works of Bach’ musician were clearly laid in the careful cultivation of Bach’s Given that strong foundation, it is no surprise that organ music prodigious talent as an organist whilst he was still a child. flowed from Bach’s pen throughout his life. Yet how do Bach’s Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach in 1685, and organ works cohere? For the monolithic notion of ‘The Complete after the death of his father – the director of municipal music Organ Works of Bach’ is misleading. -

J. S. Bach and His Legacy Program

J. S. Bach and His Legacy Program Organist: Dr. Robert Parkins March 21, 2021 Prelude and Fugue in E Minor, BWV 533 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig, BWV 618 Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV 543 O Mensch, bewein dein’ Sünde gross, BWV 622 Sonata in F Minor, Op. 65, No. 1 Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) Allegro moderato e serioso Adagio Andante recitativo Allegro assai vivace Fugue on the Name BACH, Op. 60, No. 3 Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Prelude and Fugue in A Minor Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) O Welt, ich muss dich lassen, Op. 122, No. 3 Introduction and Passacaglia in D Minor Max Reger (1873–1916) Performed on the Benjamin N. Duke Memorial Organ (Flentrop, 1976) Program Notes Although celebrated mainly as an organist during his lifetime, later generations would come to revere Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) as the unparalleled master of composition for the organ. When the great com- poser’s complex harmony and counterpoint had been eclipsed by changes in musical fashion after his death, organ music also experienced a considerable decline. Although Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s Three Preludes and Fugues for organ (1837) reflect the influence of Bach and the late Baroque, it was the publication of hisSix Sonatas in 1845 that signaled the resurgence of significant organ music in Germany. The legacy of J. S. Bach as a historical model was most profound among German Romantic composers, notably Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Max Reger. In 1829, Mendelssohn had already initi- ated a Bach revival with his celebrated performance of the St. -

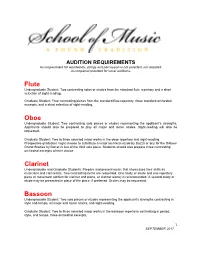

Audition Requirements 2

AUDITION REQUIREMENTS Accompaniment for woodwinds, strings and percussion is not provided, nor required. Accompanist provided for vocal auditions. Flute Undergraduate Student: Two contrasting solos or etudes from the standard flute repertory and a short selection of sight-reading. Graduate Student: Four contrasting pieces from the standard flute repertory, three standard orchestral excerpts, and a short selection of sight-reading. Oboe Undergraduate Student: Two contrasting solo pieces or etudes representing the applicant’s strengths. Applicants should also be prepared to play all major and minor scales. Sight-reading will also be requested. Graduate Student: Two to three selected major works in the oboe repertory and sight-reading. Prospective graduates might choose to substitute a major technical etude by Bozza or any for the Sixteen Grand Studies by Barret in lieu of the third solo piece. Students should also prepare three contrasting orchestral excerpts of their choice. Clarinet Undergraduate and Graduate Students: Prepare and present music that showcases their skills as musicians and clarinetists. Two contrasting items are requested. One study or etude and one repertory piece or movement (written for clarinet and piano, or clarinet alone) is recommended. A second study or etude may be presented in place of the piece, if preferred. Scales may be requested. Bassoon Undergraduate Student: Two solo pieces or etudes representing the applicant’s strengths contrasting in style and tempo, all major and minor scales, and sight-reading. Graduate Student: Two to three selected major works in the bassoon repertoire contrasting in period, style, and tempo, three orchestral excerpts. 1 SEPTEMBER 2017 Saxophone Undergraduate Student: Two contrasting movements or works from the saxophone repertoire.