820 John Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) "» United States Department of the Interior ' .J National Park Service Lui « P r% o "•> 10Q1 M!" :\ '~J <* »w3 I National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name_________1411 Fourth Avenue Building_____________________________ other names/site number N/A „ 2. Location street & number 1411 Fourth Ave. D not for publication city, town Seattle IZ1 vicinity state Washington code WA county King code 033 zip code 98101 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property IS private K] building(s) Contributing Noncontributing [U public-local C] district 1 _ buildings D public-State IH site _ _ sites C~l public-Federal [U structure _ _ structures CH object objects 1 0 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A_________________ listed in the National Register 0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this DO nomination CD request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places ancfVneets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 . -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Bon Marche Department Store other names/site number Bon Marche Building; Macy’s Building 2. Location street & number 300 Pine Street not for publication city or town Seattle vicinity state WASHINGTON code WA county KING code 033 zip code 98122 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title Date WASHINGTON SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Hutchinson Hall UW Historic Resources Addendum

Hutchinson Hall UW Historic Resources Addendum BOLA Architecture + Planning June 8, 2012 1. INTRODUCTION Background The University of Washington is proposing to reroof portions of Hutchinson Hall, which was built in 1927 as the Women’s Physical Education Building. The building is located in the north area of campus, which dates from its establishment in the late 19th century. The proposed project will involve repairs or replacement of deteriorated, original and non-original roofing, which consists of slate and composition shingles, as well as membrane materials at built-in gutters and flat roof areas. The original roof also has copper flashing, ridge cresting, eave gutters and downspouts. Consistent with its historic preservation policies, as outlined in its “University of Washington Master Plan—Seattle Campus” of January 2003 (2003 Seattle Campus Master Plan), the University of Washington sought historic and urban design information about Hutchinson Hall in a Historic Resources Addendum (HRA). This type of report is developed for any project that makes exterior alterations to a building over 50 years old, or is adjacent to a building or a significant campus feature older than 50 years. Hutchinson Hall is subject to this requirement because of its age. An HRA is required also for public spaces identified in Fig. III-2 of the 2003 Seattle Campus Master Plan. This report provides historical and architectural information about the building, a preliminary evaluation of its historic significance to the University, information about the proposed project, and recommendations. A bibliography and list of source documents is provided at the end of the text, followed by original drawings, building plans, and historic and contemporary photographs. -

Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant 1930-31; Addition, 1947

Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant 1930-31; Addition, 1947 1120 John Street 1986200525 see attached page D.T. Denny’s 5th Add. 110 7-12 Onni Group Vacant 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 The Blethen Corporation (C. B. Blethen) (The Seattle Times) Printing plant and offices Robert C. Reamer (Metropolitan Building Corporation) , William F. Fey, (Metro- politan Building Corporation) Teufel & Carlson Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant Landmark Nomination, October 2014 LEGAL DESCRIPTION: LOTS 7 THROUGH 12 IN BLOCK 110, D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION TO NORTH SEAT- TLE, AS PER PLAT RECORDED IN VOLUME 1 OF PLATS, PAGE 202, RECORDS OF KING COUNTY; AND TOGETHER WITH THOSE PORTIONS OF THE DONATION CLAIM OF D.T. DENNY AND LOUIS DENNY, HIS WIFE, AND GOVERNMENT LOT 7 IN THE SOUTH- EAST CORNER OF SECTION 30, TOWNSHIP 25, RANGE 4 EAST, W. M., LYING WEST- ERLY OF FAIRVIEW AVENUE NORTH, AS CONDEMNED IN KING COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT CAUSE NO. 204496, AS PROVIDE BY ORDINANCE NO. 51975, AND DESCRIBED AS THAT PORTION LYING SOUTHERLY OF THOMAS STREET AS CONVEYED BY DEED RECORDED UNDER RECORDING NO. 2103211, NORTHERLY OF JOHN STREET, AND EASTERLY OF THE ALLEY IN SAID BLOCK 110; AND TOGETHER WITH THE VACATED ALLEY IN BLOCK 110 OF SAID PLAT OF D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION, VACATED UNDER SEATTLE ORDINANCE NO. 89750; SITUATED IN CITY OF SEATTLE, COUNTY OF KING, STATE OF WASHINGTON. Evan Lewis, ONNI GROUP 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 T: (604) 602-7711, [email protected] Seattle Times Building Complex-Printing Plant Landmark Nomination Report 1120 John Street, Seattle, WA October 2014 Prepared by: The Johnson Partnership 1212 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-6724 206-523-1618, www.tjp.us Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant Landmark Nomination Report October 2014, page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Historic Seattle

Historic seattle 2 0 1 2 p r o g r a m s WHat’s inside: elcome to eattle s premier educational program for learning W s ’ 3 from historic lovers of buildings and Heritage. sites open to Each year, Pacific Northwest residents enjoy our popular lectures, 4 view tour fairs, private home and out-of-town tours, and special events that foster an understanding and appreciation of the rich and varied built preserving 4 your old environment that we seek to preserve and protect with your help! house local tours 5 2012 programs at a glance January June out-of-town 23 Learning from Historic Sites 7 Preserving Utility Earthwise Salvage 5 tour Neptune Theatre 28 Special Event Design Arts Washington Hall Festive Partners’ Night Welcome to the Future design arts 5 Seattle Social and Cultural Context in ‘62 6 February 12 Northwest Architects of the Seattle World’s Fair 9 Preserving Utility 19 Modern Building Technology National Archives and Record Administration preserving (NARA) July utility 19 Local Tour 10 Preserving Utility First Hill Neighborhood 25 Interior Storm Windows Pioneer Building 21 Learning from Historic Sites March Tukwila Historical Society special Design Arts 11 events Arts & Crafts Ceramics August 27 Rookwood Arts & Crafts Tiles: 11 Open to View From Cincinnati to Seattle Hofius Residence 28 An Appreciation for California Ceramic Tile Heritage 16 Local Tour First Hill Neighborhood April 14 Preserving Your Old House September Building Renovation Fair 15 Design Arts Cover l to r, top to bottom: Stained Glass in Seattle Justinian and Theodora, -

Report on Designation Lpb 181/09

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 181/09 Name and Address of Property: Naval Reserve Armory 860 Terry Avenue North Legal Description: Lots 9-13, inclusive, Block 74, Lake Union Shore Lands. Together with any and all rights to the east half of abutting street, being Terry Avenue North as shown on the ALTA/ASCM Land Title Survey of US NAVAL RESERVE CENTER SOUTH LAKE UNION dated Dec. 3, 1998. Recording number 9506309003, Volume 104, Page 116. At the public meeting held on March 18, 2009, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the Naval Reserve Armory at 860 Terry Avenue North Street as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standards for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction; and F. Because of its prominence of spatial location, contrasts of siting, age, or scale, it is an easily identifiable visual feature of its neighborhood or the city and contributes to the distinctive quality or identity of such neighborhood or the City. DESCRIPTION The South Lake Union neighborhood is located north of the city's Central Business District, and north and east of Belltown. It is bordered by the lake on the north, Interstate 5 on the east, Denny Way on the south, and Highway 99/Aurora Avenue on the west. -

Volunteer Handbook

VOLUNTEER HANDBOOK 2017 The Center for Wooden Boats Your guide to the History, People & Procedures of The Center for Wooden Boats Change Cover Picture to WEC? There is an aerial photo on The Center for Wooden Boats Facebook that includes the Center for Wooden Boats and WEC - Kalisto WELCOME! Our volunteers truly are the fabric that holds us all together. Each year our volunteers donate more than 15,000 hours of their time to all facets of the organization. From the Boat shop, Livery, and Front Desk to Special Events and Festivals – volunteers keep our programs vibrant and alive. Indeed, the individuals are as varied as their work. Our volunteers range from 15 years old to 90+, hail from the West Coast and distant lands, and, while some have been with us for 20 years or more, we welcome new volunteers into the fold every month. Whether you stay with us for 6 months or 16 years, we hope your volunteer experiences provide you with opportunities to engage in our community, learn new skills, meet new people, and have a rollicking good time with boats! Welcome! We’re so happy to have you aboard. LETTER FROM THE FOUNDING DIRECTOR A museum where you can play with the exhibits! What a concept! CWB’s mission is simple and direct: preserving our small craft heritage. Our collections are for education. The most lasting means of education is direct experience. To do is to learn. We want everyone to come here. That’s why we don’t charge admission. Yet, most of our income is from earnings and small private donations. -

Seattle Host Committee Guide — ICMA's 101St Annual Conference

WELCOME TO THE Emerald City! Surrounded by the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, Lake Washington, and Puget Sound, Seattle and King County offer a rich history, one-of-a-kind attractions, a thriving cultural scene, world-class restaurants and shopping, and boundless opportunities for outdoor adventure. The Host Committee is excited to host the 101st ICMA Annual Conference and welcome you to our home. We invite you to explore the down-to-earth charm and rugged beauty of the Pacific Northwest. Read on for an introduction to some of our favorite activities and attractions throughout the region. One-of-a-Kind Attractions Within just a few blocks of the Seattle Waterfront, you’ll find many of our region’s top visitor destinations, including Pike Place Market, the Space Needle and Seattle Center, and historic Pioneer Square. • The famed Pike Place Market is a bazaar the Seattle Aquarium, and catch breathtaking views of of fresh flowers, fruit, seafood, vegetables, the skyline and Mount Rainier from the Seattle Great ethnic eateries, and specialty shops over- Wheel, a 175-foot Ferris wheel at Pier 57. looking Elliott Bay. The oldest continually • Constructed for the 1962 World's Fair, Seattle Center operating farmers market in the United is home to our city’s most recognizable symbol, the States, this is the place to watch fish- Space Needle. At Seattle Center, you can journey sky- mongers tossing salmon, sample coffee ward for a panoramic view of Puget Sound from the at the original Starbucks location, and Space Needle’s Observation Deck, glide downtown enjoy the music and antics of street aboard the Seattle Monorail, or play in the waters of the performers. -

Preservation News the Newsletter of Historic Seattle Educate

Preservation news the newsletter of Historic Seattle Educate. Advocate. Preserve. volume 38 issue 2 Preservation is More Than Just Bricks and Mortar September 2012 Too often, the pros and cons of saving or razing an historic building revolve around architectural significance, structural integrity, obsolescence, and the cost to bring it up to code and its systems into the 21st century. What sometimes gets lost In This Issue: or is relegated to a minor role is the value the building has had to generations of residents and workers and the direct and indirect impacts on Free Mukai our economic, social, and cultural identity this pg 2 brings to the discussion. For several years, Historic and Parks Resources of Natural King County Dept. Fall and Winter Seattle has been involved with a number of local Nurse Cadet Corps in front of Harborview Hall, 1944 Events groups in making a case for preserving Harborview pg 4 Hall on First Hill. that sheds light on the people who are most associated We asked Carolyn Duncan, Special Projects Manager, with this important building—nurses. To see an Preservation King County Department of Natural Resources and informative video about the hall and residents, go to: Advocacy in the Parks to discuss her important video interview project www.kingcounty.gov/property/historic-preservation.aspx Pike/Pine Neighborhood pg 5 Life in Harborview Hall emailed me from Gaza where she was performing by Carolyn Duncan community service. One of the first African-American Washington Hall As a reporter in the students at the University of Washington School Update 1980s I knew that people of Nursing, 91-year old Thelma Pegues, earned a pg 7 made a story come alive. -

TRUSTNEWS January 2011 Renaissance in the Making: Three Stories from Roslyn

TRUSTNEWS January 2011 Renaissance in the making: Three stories from Roslyn INSIDE: NEW DESIGN, NEW WEBSITE The Washington Trust is sporting a new logo, new colors, and a newly designed website WASHINGTON HERITAGE AT RISK! The proposed state budget will have a major effect on heritage programs around the state LOcAL PARTNERSHIPS Historic Tacoma, continuing forward YOUR TRUST IN ACTION A new year, from the director’s desk Board of Directors By Jennifer Meisner, Executive Director President Dear Members and Friends, Paul Mann, Spokane Happy New Year to you all! 2011 marks the Washington Trust’s Vice President 35th year of working to save the historic places that tell our col- Michael Jenkins, Seattle lective stories and to promote sustainability, economic develop- Secretary ment, and community vitality through the adaptive reuse of Ginger Wilcox, Seattle historic buildings. Thanks to the vision and dedication of our past and present Board of Directors, the generosity and support Treasurer of our members, and the talent and tireless efforts of our staff, David Leal, Walla Walla the Washington Trust has provided critical support to local communities as Board Members they work to save the places that matter since our founding in 1976. Over these Kris Bassett, Wenatchee many years the Trust has grown and changed significantly, and this year we Jon Campbell, Walla Walla also celebrate the 10-year anniversary of one of the most momentous junctures Dow Constantine, Seattle in our history: the gift of the Stimson-Green Mansion from community leader Rob Fukai, Tumwater and philanthropist Patsy Bullitt Collins. The gift of the Mansion in 2001 enabled Betsy Godlewski, Spokane the Trust to exponentially expand our capacity to deliver our statewide mission Kristen Griffin, Spokane and forever changed the landscape of preservation in Washington State. -

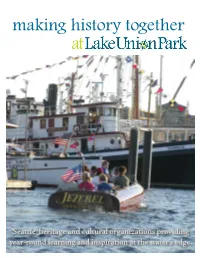

Making History Together

making history together Seattle heritage and cultural organizations providing year-round learning and inspiration at the water’s edge. P. 2 making history together Our beautiful city is fortunate to be defined by many diverse bodies of water. From Puget Sound to Lake Union through the Ship Canal to Lake Washington, from the Duwamish River to our four urban creek systems, these bodies of water in many ways define who we are as a city. They frame our sensibilities and priorities by providing habitat for mammals, fish, birds and insects. For people, they enable us to enjoy boating, fishing, kayaking, swimming, and endless beach activities. The development of Lake Union Park realizes a longtime city vision to revisit and present the rich history of the site and its relationship to the water. The Olmsted Brothers, who designed the nucleus of our park system, envisioned a grand urban park at this site. Through our partnerships with Seattle Parks Foundation, The Center for Wooden Boats, the United Indians of All Tribes, Northwest Seaport, South Lake Union Friends and Neighbors (SLUFAN), the Museum of History & Industry, and others, we are able to turn vision into reality. When newcomers first settled at the site, it was the home of the Duwamish people. Imagine their walking paths meandering through the timber, connecting the lake village with Native settlements to the east and west. Soon historic panels at the park will tell the whole history, from the arrival of the settlers through the building of the streetcar to the opening of the Ship Canal to the construction of The Boeing Airplane Company. -

Times Building Complex—1947 Office Building Addition 1930-31; Addition, 1947

Seattle Times Building Complex—1947 Office Building Addition 1930-31; Addition, 1947 1120 John Street 1986200525 see attached page D.T. Denny’s 5th Add. 110 7-12 Onni Group Vacant 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 The Blethen Corporation (C. B. Blethen) (The Seattle Times) Offices William F. Fey, (Metropolitan Building Corporation) Teufel & Carlson Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant Landmark Nomination, October 2014 LEGAL DESCRIPTION: LOTS 7 THROUGH 12 IN BLOCK 110, D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION TO NORTH SEAT- TLE, AS PER PLAT RECORDED IN VOLUME 1 OF PLATS, PAGE 202, RECORDS OF KING COUNTY; AND TOGETHER WITH THOSE PORTIONS OF THE DONATION CLAIM OF D.T. DENNY AND LOUIS DENNY, HIS WIFE, AND GOVERNMENT LOT 7 IN THE SOUTH- EAST CORNER OF SECTION 30, TOWNSHIP 25, RANGE 4 EAST, W. M., LYING WEST- ERLY OF FAIRVIEW AVENUE NORTH, AS CONDEMNED IN KING COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT CAUSE NO. 204496, AS PROVIDE BY ORDINANCE NO. 51975, AND DESCRIBED AS THAT PORTION LYING SOUTHERLY OF THOMAS STREET AS CONVEYED BY DEED RECORDED UNDER RECORDING NO. 2103211, NORTHERLY OF JOHN STREET, AND EASTERLY OF THE ALLEY IN SAID BLOCK 110; AND TOGETHER WITH THE VACATED ALLEY IN BLOCK 110 OF SAID PLAT OF D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION, VACATED UNDER SEATTLE ORDINANCE NO. 89750; SITUATED IN CITY OF SEATTLE, COUNTY OF KING, STATE OF WASHINGTON. Evan Lewis, ONNI GROUP 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 T: (604) 602-7711, [email protected] Seattle Times Building Complex-1947 Office Building Additon Landmark Nomination Report 1120 John Street, Seattle, WA October 2014 Prepared by: The Johnson Partnership 1212 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-6724 206-523-1618, www.tjp.us 1120 John Street-Seattle Times 1947 Office Building Addition Landmark Nomination Report October 2014, page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.