The God-Seeker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was Gen. Henry Sibley's Son Hanged in Mankato?

The Filicide Enigma: Was Gen. Henry Sibley’s Son Ha nged in Ma nkato? By Walt Bachman Introduction For the first 20 years of Henry Milord’s life, he and Henry Sibley both lived in the small village of Mendota, Minnesota, where, especially during Milord’s childhood, they enjoyed a close relationship. But when the paths of Sibley and Milord crossed in dramatic fashion in the fall of 1862, the two men had lived apart for years. During that period of separation, in 1858 Sibley ascended to the peak of his power and acclaim as Minnesota’s first governor, presiding over the affairs of the booming new state from his historic stone house in Mendota. As recounted in Rhoda Gilman’s excellent 2004 biography, Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart, Sibley had occupied key positions of leadership since his arrival in Minnesota in 1834, managing the regional fur trade and representing Minnesota Territory in Congress before his term as governor. He was the most important figure in 19th century Minnesota history. As Sibley was governing the new state, Milord, favoring his Dakota heritage on his mother’s side, opted to live on the new Dakota reservation along the upper Minnesota River and was, according to his mother, “roaming with the Sioux.” Financially, Sibley was well-established from his years in the fur trade, and especially from his receipt of substantial sums (at the Dakotas’ expense) as proceeds from 1851 treaties. 1 Milord proba bly quickly spe nt all of the far more modest benefit from an earlier treaty to which he, as a mixed-blood Dakota, was entitled. -

Special 150Th Anniversary Issue Ramsey County and Its Territorial Years —Page 8

RAMSEY COUNTY In the Beginning: The Geological Forces A Publication o f the Ramsey County Historical Society That Shaped Ramsey County Page 4 Spring, 1999 Volume 34, Number 1 Special 150th Anniversary Issue Ramsey County And Its Territorial Years —Page 8 “St. Paul in Minnesotta, ” watercolor, 1851, by Johann Baptist Wengler. Oberösterreichisches Landes Museum, Linz, Austria. Photo: F. GangI. Reproduced by permission of the museum. Two years after the establishment of Minnesota Territory, St. Paul as its capital was a boom town, “... its situation is as remarkable for beauty as healthiness as it is advantageous for trade, ” Fredrika Bremer wrote in 1853, and the rush to settlement was on. See “A Short History of Ramsey County” and its Territorial Years, beginning on page 8. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham An Exciting New Book Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz for Young Readers RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 34, Number 1 Spring, 1999 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Laurie A. Zenner CONTENTS Chair Howard M. Guthmann President James Russell 3 Message from the President First Vice President Anne Cowie Wilson 4 In the Beginning Second Vice President The Geological Forces that Shaped Ramsey Richard A. Wilhoit Secretary County and the People Who Followed Ronald J. Zweber Scott F. Anfinson Treasurer W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Charlotte H. 8 A Short History of Ramsey County— Drake, Mark G. Eisenschenk, Joanne A. Eng- lund, Robert F. Garland, Judith Frost Lewis, Its Territorial Years and the Rush to Settlement John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Marlene Marschall, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Bob Olsen, 2 2 Ramsey County’s Heritage Trees Linda Owen, Fred Perez, Marvin J. -

Pembina's Pious Pioneers

VISITING OUR NORTHERN BORDER: PEMBINA’S PIOUS PIONEERS No, I was not sick last Sunday, but you might say I was playing “hooky,” making a “run for the (northern) border.” No, not to Taco Bell, but I did attend a wonderful celebration in Pembina (population 563) in the extreme northeast corner of North Dakota. Here’s a little background. In September of 1818, the Bishop of Quebec sent Fr. Josef Dumoulin to a settlement known today as St. Boniface, Manitoba, the “twin city” to Winnipeg, separated by the Red River. Indeed, that’s the same Red River that separates Northern Minnesota from North Dakota, infamous for its occasional floods. When numerous families fled due to the destruction of their crops by grasshoppers, Dumoulin was dispatched about 60 miles due south to a settlement called Pembina, still part of the Red River Colony established by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Life was not easy in the northern plains of today’s Manitoba. But, obedient to his superior, the intrepid missionary administered the sacraments faithfully to the small community entrusted to his care. All went relatively well until he was recalled for reasons completely beyond his control. In October of 1818, a treaty was negotiated between the Monroe Administration and the British, attempting to settle once for all the border questions between their respective lands following the War of 1812. After a little horse trading, the United States ceded some territory north of Montana to the British. In return, we acquired substantial acreage in northwest Minnesota and North Dakota that was not included in the Louisiana Purchase. -

Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: a History of Crow Creek Tribal School

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2000 Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School Robert W. Galler Jr. Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Galler, Robert W. Jr., "Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School" (2000). Dissertations. 3376. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3376 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVIRONMENT, CULTURES, AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE GREAT PLAINS: A HISTORY OF CROW CREEK TRIBAL SCHOOL by Robert W. Galler, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2000 Copyright by Robert W. Galler, Jr. 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people provided assistance, suggestions, and support to help me complete this dissertation. My study of Catholic Indian education on the Great Plains began in Dr. Herbert T. Hoover's American Frontier History class at the University of South Dakota many years ago. I thank him for introducing me to the topic and research suggestions along the way. Dr. Brian Wilson helped me better understand varied expressions of American religious history, always with good cheer. -

History of Saint Agnes

Preface A hundred years in the life of a man or woman is a long time. In the existence of institutions, especially the Church, a hundred years is as yesterday. But it is good to mark the passing of time, such as a hundred years, and occasionally to look back and assess the events that have occurred, the people who have lived, and the things that have been accomplished. A history of a parish needs be a chronicle of events to a large extent. Judgment on those events is not always possible or necessary and perhaps not even wise. The important thing is that the events and the facts of the past hundred years be recorded as clearly and precisely as possible so that someday someone may wish to have them and use them. Colligite fragmenta ne pereant (Collect the fragments lest they be lost). An old Latin adage says Nemo est judex in causa sua (No one is a judge in his own case). With that in mind, I freely submit that the events chronicled here from 1969 to the present have passed through the judgment of the author, who is the pastor whose time of tenure is being described. I have tried to give a fair picture. Another writer can make the judgment if he so chooses. Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Chapter 1 EUROPE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century was still living under the effects of the French Revolution, the wars of Napoleon and the rise of liberalism. The unification of Germany and the Risorgimento in Italy had caused grave problems for the Church, and the power and the prestige of the papacy had suffered from these political events. -

History of Minnesota and Tales of the Frontier.Pdf

'•wii ^.^m CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Sejmour L. Green . i/^^ >/*--*=--— /o~ /^^ THE LATE JUDGE FLANDRAU. He Was Long a Prominent Figure in tbej West. 4 Judge Charles E. Flandrau, whose death!/ occurred in St. Paul,- Minn., as previously f noted, was a prbmlnfent citizen in the Mid- i die West. Judge Flandrau was born in , New York city in 1828 and when a- mere | boy he entered the government service on ' the sea and remained three years. Mean- i time his -father, who had been a law part- ner of Aaron Burr, moved to Whltesboro, and thither young Flandrau went and stud- ied law. In 1851 he was admitted to 'the i bar and became his father's partner. Two years later he went to St. Paul, which I had since been his home practically all the tune. in 1856 he was appointed Indian agent for the Sioux of the JVlississippi, and did notable work in rescuing hundreds of refu- gees from the hands of the blood-thirsty reds. In 1857 he became a member of the constitutional convention Which framed" the constitution of the state, and sat -is a Democratic member of the convention, which was presided over by Govei-nor Sib- ley. At this time he was also appointed an associate justice of -the Supreme Court of Minnesota, ' retainitig his place on the bench until 1864. In 1863 he became Judge advocate general, which position he held concurrently with the .iusticesbip. It was during the Siolix rebellion of 1862 that Judge Flandrau performed his most notable services for the state, his cool sagacity and energy earning for him a name that endeared him to the people of the state for all time. -

Digitization of Museum Collections: Using Technology, Creating Access, and Releasing Authority in Managing Content and Resources Benjamin S

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Department of Anthropology Management 5-2015 Digitization of Museum Collections: Using Technology, Creating Access, and Releasing Authority in Managing Content and Resources Benjamin S. Gessner St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gessner, Benjamin S., "Digitization of Museum Collections: Using Technology, Creating Access, and Releasing Authority in Managing Content and Resources" (2015). Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management. 3. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds/3 This Creative Work is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitization of Museum Collections: Using Technology, Creating Access, and Releasing Authority in Managing Content and Resources By Benjamin S. Gessner B.F.A., Minnesota State University, Mankato, 2004 M.A., Minnesota State University, Mankato, 2006 A Creative Work Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science St. Cloud, Minnesota March, 2015 This creative work submitted by Benjamin S. Gessner in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at St. Cloud State University is hereby approved by the final evaluation committee. ________________________________ Dr. Mark Muñiz, Chairperson ________________________________ Dr. Kelly Branam ________________________________ Darlene St. -

New Light on Old St. Peter's and Early St. Paul

NEW LIGHT ON OLD ST. PETER'S AND EARLY ST. PAUL Who the settlers of the Grand Marais, of the old Fort Snell- ing reservation, and of other points in the vicinity of St. Paul before the founding of the city in 1840 and 1841 actually were, is known today only in part.^ Many picturesque figures of that day have silently melted into oblivion, leaving few traces behind them. Since it was from these settlers, known and unknown, that the nucleus of the population of the St. Paul of 1840 and the years immediately following was formed, historical sidelights on these pioneers are piquantly interesting as well as important in the early history of Minnesota. One of these sidelights, enchanting and vivid, is reflected in the records of the pioneer missionary trip of Bishop Mathias Loras of Dubuque to St. Peter's in 1839. In that year, the portion of the present state of Minnesota which lies west of the Mississippi was part of Iowa Territory. It was also part of the diocese of Dubuque, then but recently established. This diocese was immense as it originally stood; it re.ached northward from the northern line of Missouri to the boundary of British America, and westward from the Mississippi River to the Missouri.^ It included what is now the state of Iowa, most of Minnesota, and large portions of North and South Dakota. Save one other, this diocese con tained the largest number of Indians, about thirty thousand.^ Zealous for the conversion of these aborigines and desiring to view the northern parts of his far-flung province, the Right Reverend Mathias Loras, the first bishop of " Du Buque " as 1 Pig's Eye Lake was known as the Grand Marais by the French traders and voyageurs. -

The Impact of Dakota Missions on the Development of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2012 The Impact of Dakota Missions on the Development of the U.S.- Dakota War of 1862 Daphne D. Hamborg Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hamborg, D. D. (2012). The impact of Dakota Missions on the development of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/4/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. The Impact of Dakota Missions on the Development of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 By Daphne D. Hamborg A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master of Science Department of Anthropology Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, MN May 2012 This report is submitted as part of the required work in the Department of Anthropology, ANTH 699, 3.00, Thesis, at Minnesota State University, Mankato, and has been supervised, examined, and accepted by the Professor. -

PDF of Book Review

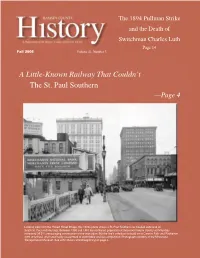

The 1894 Pullman Strike and the Death of Switchman Charles Luth Page 14 Fall 2006 Volume 41, Number 3 A Little-Known Railway That Couldn’t The St. Paul Southern —Page 4 Looking west from the Robert Street Bridge, this 1920s photo shows a St. Paul Southern car headed outbound for South St. Paul and Hastings. Between 1900 and 1910 the combined population of these two Dakota County communities increased 38.5%, encouraging construction of the interurban. But the line’s ambitions to build on to Cannon Falls and Rochester went unfulfilled, and it eventually succumbed to automobile and bus competition. Photograph courtesy of the Minnesota Transportation Museum. See John Diers’s article beginning on page 4. History Fall 06.pdf 1 11/28/06 11:25:26 AM RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director RAMSEY COUNTY Priscilla Farnham Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 41, Number 3 Fall 2006 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY the mission statement of the ramsey county historical society BOARD OF DIRECTORS adopted by the board of directors in July 2003: Howard Guthmann Chair The Ramsey County Historical Society shall discover, collect, W. Andrew Boss preserve and interpret the history of the county for the general public, President recreate the historical context in which we live and work, and make Judith Frost Lewis First Vice President available the historical resources of the county. The Society’s major Paul A. Verret responsibility is its stewardship over this history. Second Vice President Joan Higinbotham Secretary C O N T E N T S J. -

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of the John

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of TiGze John 4reland Papers Scott Jessee Minnesota Historical Society * St. Paul * 1984 Copyright " 1984 by the Minnesota Historical Society International Standard Book Number: 0-87351-168-9 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 84-60157 This pamphlet and the ~nicrofilrnedition of the John Ireland Papers it describes were made possible by grants of funds from the National Historical Publications and aecords Commission, the Northwest Area Foundation, and the Catholic Historical Society to the Minnesota Historical Society. Foreword John Ireland (1838-1918) was one of the most important figures in American Catholic history. Born in Ireland, raised in Minnesota, and educated for the , priesthood in France, he was ordained for the Diocese of St. Paul in 1861. In 1862-1863 he served as chaplain to the Fifth Minnesota Volunteers. In 1869- / 1870 he represented his bishop, Thomas Grace, at the First Vatican Council. I Named vicar apostolic of the Nebraska Territory in 1875, he was immediately i renamed, at Bishop Grace's request, coadjutor of St. Paul. He succeeded to : that see in 1884 and attended the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore. In 1888, he was named the first archbishop of St. Paul. A dynamic speaker and lucid writer in both English and French, Ireland rapidly became the dominant figure in the liberal party that emerged in the ' American hierarchy after the Third Plenary Council. His influence over other members of that party is indicated by the extensive correspondence to him from Cardinal James Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore; John J. Keane, 8 successively bishop of Richmond, first rector of the Catholic University of 1 America, titular archbishop of Damascus, and archbishop of Dubuque; and I Denis J. -

This Item Is a Finding Aid to a Proquest Research Collection in Microform

This item is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 This product is no longer affiliated or otherwise associated with any LexisNexis® company. Please contact ProQuest® with any questions or comments related to this product. About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world’s knowledge – from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway ■ P.O Box 1346 ■ Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ■ USA ■ Tel: 734.461.4700 ■ Toll-free 800-521-0600 ■ www.proquest.com A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of Henry Hastings Sibley: Fur Trader, Politician, and General A UPA Collection from Cover: Henry Hastings Sibley (1811–1891. Portrait in the possession of the Sibley House Association, Minnesota Daughters of the American Revolution. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. Papers of Henry Hastings Sibley: Fur Trader, Politician, and General Guide by Norma L. Wark A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road ● Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Copyright © 2008 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-966-6. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................