Digitization of Museum Collections: Using Technology, Creating Access, and Releasing Authority in Managing Content and Resources Benjamin S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing of Menthol Cigarettes and Consumer Perceptions Joshua Rising1*, Lori Alexander2

Rising and Alexander Tobacco Induced Diseases 2011, 9(Suppl 1):S2 http://www.tobaccoinduceddiseases.com/content/9/S1/S2 REVIEW Open Access Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions Joshua Rising1*, Lori Alexander2 Abstract In order to more fully understand why individuals smoke menthol cigarettes, it is important to understand the perceptions held by youth and adults regarding menthol cigarettes. Perceptions are driven by many factors, and one factor that can be important is marketing. This review seeks to examine what role, if any, the marketing of menthol cigarettes plays in the formation of consumer perceptions of menthol cigarettes. The available literature suggests that menthol cigarettes may be perceived as safer choices than non-menthol cigarettes. Furthermore, there is significant overlap between menthol cigarette advertising campaigns and the perceptions of these products held by consumers. The marketing of menthol cigarettes has been higher in publications and venues whose target audiences are Blacks/African Americans. Finally, there appears to have been changes in cigarette menthol content over the past decade, which has been viewed by some researchers as an effort to attract different types of smokers. Review Summarized in this review are 35 articles found to The marketing of cigarettes is a significant expenditure have either direct relevance to these questions, or were for the tobacco industry; in 2006, the tobacco industry used to provide relevant background information. Many spent a total of $12.49 billion on advertising and promo- ofthesearticleswereidentifiedthroughareviewofthe tion of cigarettes including menthol brands, which literature conducted by the National Cancer Institute in represent 20% of the market share [1]. -

EDUCATION BANQUET Wednesday, June 5Th 5:00 P.M. Dacotah

June 2019 Volume 19 Issue 6 COUNCIL Robert L. Larsen, Sr. President EDUCATION BANQUET Grace Goldtooth Wednesday, June 5th Vice-President 5:00 p.m. Earl Pendleton Treasurer Dacotah Exposition Center Jane Steffen RSVP @ www.eventbrite.com Secretary Kevin O’Keefe Assistant Secretary/ Treasurer GROUND BLESSING & ROYALTY Wednesday, June 12th 1:00 p.m. Royalty to follow. WACIPI STIPEND Qualified Members INSIDE Wednesday, June 12th at 8:30-4:30 TH IS IS SUE LSIC Government Center Health 2-5 Tiosaype/THPO 6 Environment 8 Housing 9 Lower Sioux Indian Community Head Start 10 Wounspe 11 NOMINATIONS Community News 12-13 Two Council Seats Lower Sioux Wacipi 14 Wednesday, June 19th, 2019 Rec. Calendar 15 Multi-purpose Room at 5:00 p.m. Calendar 16 www.lowersioux.com 2 HEALTH HEALTH REMINDERS GROCERY STORE TOURS- Please call Stacy at 697-8600 to set up a time and date for your group or individualized tour. HEALTH CORRESPONDENCE-Bring mail and correspondence you receive into health department. HOME HEALTH VISIT-Interested in a home health visit inclusive of blood pressure, blood glucose monitoring, health promotion, health concerns, medication management, hospital discharge visit? Contact Lower Sioux Community Health Nurse at 507-697-8940. • INSURANCE-CCStpa will cover electric breast pumps up to $300.00. • NUTRITION SERVICES OFFERED-If your Physician or primary care provider has referred you to a Registered Dietitian, please schedule an appointment with Stacy at 697-8600. PARENTS OF NEWBORN BABIES: • Must visit the Health Department within the first thirty (30) day of Birth, if your newborn is not registered within the first thirty (30) days of birth there will not be insurance coverage • Register for Health Insurance and Indian Health • Newborns will not be eligible for insurance until the open enrollment unless you follow the steps COMMUNITY HEALTH Health Care Assistants Community Health will assign a Health Care Assistant to provide services to those needing assistance. -

Native American Context Statement and Reconnaissance Level Survey Supplement

NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for The City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC FINAL July 2016 Cover Image Indian Tepees on the Site of Bridge Square with the John H. Stevens House, 1852 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 583) Minneapolis Pow Wow, 1951 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 35609) Minneapolis American Indian Center 1530 E Franklin Avenue NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development 250 South 4th Street Room 300, Public Service Center Minneapolis, MN 55415 Prepared by Eva B. Terrell, M.A. and Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 FINAL July 2016 MINNEAPOLIS NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT This project is funded by the City of Minneapolis and with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. -

Native American Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Ethnozoology Herman A

IK: Other Ways of Knowing A publication of The Interinstitutional Center for Indigenous Knowledge at The Pennsylvania State University Libraries Editors: Audrey Maretzki Amy Paster Helen Sheehy Managing Editor: Mark Mattson Associate Editor: Abigail Houston Assistant Editors: Teodora Hasegan Rachel Nill Section Editor: Nonny Schlotzhauer A publication of Penn State Library’s Open Publishing Cover photo taken by Nick Vanoster ISSN: 2377-3413 doi:10.18113/P8ik360314 IK: Other Ways of Knowing Table of Contents CONTENTS FRONT MATTER From the Editors………………………………………………………………………………………...i-ii PEER REVIEWED Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western Science for Optimal Natural Resource Management Serra Jeanette Hoagland……………………………………………………………………………….1-15 Strokes Unfolding Unexplored World: Drawing as an Instrument to Know the World of Aadivasi Children in India Rajashri Ashok Tikhe………………………………………………………………………………...16-29 Dancing Together: The Lakota Sun Dance and Ethical Intercultural Exchange Ronan Hallowell……………………………………………………………………………………...30-52 BOARD REVIEWED Field Report: Collecting Data on the Influence of Culture and Indigenous Knowledge on Breast Cancer Among Women in Nigeria Bilikisu Elewonibi and Rhonda BeLue………………………………………………………………53-59 Prioritizing Women’s Knowledge in Climate Change: Preparing for My Dissertation Research in Indonesia Sarah Eissler………………………………………………………………………………………….60-66 The Library for Food Sovereignty: A Field Report Freya Yost…………………………………………………………………………………………….67-73 REVIEWS AND RESOURCES A Review of -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Was Gen. Henry Sibley's Son Hanged in Mankato?

The Filicide Enigma: Was Gen. Henry Sibley’s Son Ha nged in Ma nkato? By Walt Bachman Introduction For the first 20 years of Henry Milord’s life, he and Henry Sibley both lived in the small village of Mendota, Minnesota, where, especially during Milord’s childhood, they enjoyed a close relationship. But when the paths of Sibley and Milord crossed in dramatic fashion in the fall of 1862, the two men had lived apart for years. During that period of separation, in 1858 Sibley ascended to the peak of his power and acclaim as Minnesota’s first governor, presiding over the affairs of the booming new state from his historic stone house in Mendota. As recounted in Rhoda Gilman’s excellent 2004 biography, Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart, Sibley had occupied key positions of leadership since his arrival in Minnesota in 1834, managing the regional fur trade and representing Minnesota Territory in Congress before his term as governor. He was the most important figure in 19th century Minnesota history. As Sibley was governing the new state, Milord, favoring his Dakota heritage on his mother’s side, opted to live on the new Dakota reservation along the upper Minnesota River and was, according to his mother, “roaming with the Sioux.” Financially, Sibley was well-established from his years in the fur trade, and especially from his receipt of substantial sums (at the Dakotas’ expense) as proceeds from 1851 treaties. 1 Milord proba bly quickly spe nt all of the far more modest benefit from an earlier treaty to which he, as a mixed-blood Dakota, was entitled. -

Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Hemp Economic Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report 1 March 2019

Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Hemp Economic Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report 1 March 2019 SWO Hemp Economic Feasibility Study Phase I Final Report Principal Investigators George Weiblen, Jonathan Wenger, Eric Singsaas, Clemon Dabney and Dean Current Prof. Weiblen and colleagues prepared this report on behalf of the University of Minnesota in fulfillment of sponsored project award number 00070638 (31 May 2018 - 31 December 2018). Bell Museum and Department of Plant & Microbial Biology 140 Gortner Laboratory 479 Gortner Avenue Saint Paul, Minnesota 55108 [email protected] Table of Contents Rationale .......................................................................................................................... 2 Project History ........................................................................................................................... 2 Project Team ............................................................................................................................. 2 Background ............................................................................................................................... 2 Study Objectives .............................................................................................................. 4 Hemp Fiber Crop Demonstration .............................................................................................. 4 Cost and Needs Assessment for Hemp Production, Processing and Manufacturing ............... 7 Market Opportunity and Economic Feasibility ........................................................................ -

Little Crow Historic Canoe Route

Taoyateduta Minnesota River HISTORIC water trail BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA Twin Valley Council U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 AUGUST 17, 1862 The TA-OYA-TE DUTA Fish and Wildlife Minnesota River Historic Water Four Dakota men kill five settlers The Minnesota River Basin is a Trail, is an 88 mile water route at Acton in Meeker County birding paradise. The Minnesota stretching from just south of AUGUST 18 River is a haven for bird life and Granite Falls to New Ulm, Minne- several species of waterfowl and War begins with attack on the sota. The river route is named af- riparian birds use the river corri- Lower Sioux Agency and other set- ter Taoyateduta (Little Crow), the dor for nesting, breeding, and rest- tlements; ambush and battle at most prominent Dakota figure in ing during migration. More than the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Redwood Ferry. Traders stores 320 species have been recorded in near Upper Sioux Agency attacked the Minnesota River Valley. - The Minnesota River - AUGUST 19 Beneath the often grayish and First attack on New Ulm leading to The name Minnesota is a Da- cloudy waters of the Minnesota its evacuation; Sibley appointed kota word translated variously as River, swim a diverse fish popula- "sky-tinted water” or “cloudy-sky tion. The number of fish species commander of U.S. troops water". The river is gentle and and abundance has seen a signifi- AUGUST 20 placid for most of its course and cant rebound over the last several First Fort Ridgely attack. one will encounter only a few mi- years. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

Special 150Th Anniversary Issue Ramsey County and Its Territorial Years —Page 8

RAMSEY COUNTY In the Beginning: The Geological Forces A Publication o f the Ramsey County Historical Society That Shaped Ramsey County Page 4 Spring, 1999 Volume 34, Number 1 Special 150th Anniversary Issue Ramsey County And Its Territorial Years —Page 8 “St. Paul in Minnesotta, ” watercolor, 1851, by Johann Baptist Wengler. Oberösterreichisches Landes Museum, Linz, Austria. Photo: F. GangI. Reproduced by permission of the museum. Two years after the establishment of Minnesota Territory, St. Paul as its capital was a boom town, “... its situation is as remarkable for beauty as healthiness as it is advantageous for trade, ” Fredrika Bremer wrote in 1853, and the rush to settlement was on. See “A Short History of Ramsey County” and its Territorial Years, beginning on page 8. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham An Exciting New Book Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz for Young Readers RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 34, Number 1 Spring, 1999 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Laurie A. Zenner CONTENTS Chair Howard M. Guthmann President James Russell 3 Message from the President First Vice President Anne Cowie Wilson 4 In the Beginning Second Vice President The Geological Forces that Shaped Ramsey Richard A. Wilhoit Secretary County and the People Who Followed Ronald J. Zweber Scott F. Anfinson Treasurer W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Charlotte H. 8 A Short History of Ramsey County— Drake, Mark G. Eisenschenk, Joanne A. Eng- lund, Robert F. Garland, Judith Frost Lewis, Its Territorial Years and the Rush to Settlement John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Marlene Marschall, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Bob Olsen, 2 2 Ramsey County’s Heritage Trees Linda Owen, Fred Perez, Marvin J. -

Federal Register/Vol. 71, No. 21/Wednesday, February 1, 2006/Notices

5362 Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 21 / Wednesday, February 1, 2006 / Notices Seashore, 99 Marconi Site Road, information against Primary Suitability of humans’ work substantially Wellfleet, MA 02667. Criteria, section 6.2.1.1, of Management unnoticeable; (4) the area is protected SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Policies 2001. and managed so as to preserve its assessment standards outlined in NPS Since the expansion of Redwood natural conditions; and (5) the area Management Policies (2001) to National Park in 1978, the park has offers outstanding opportunities for determine if a roadless, undeveloped undertaken an intense watershed solitude or a primitive and unconfined area is suitable for preservation as rehabilitation program with a focus on type of recreation. wilderness are that it is over 5,000 acres removing roads. Since park expansion Public notices announcing the park’s in size or of sufficient size to make in 1978, about 219 miles of road have intention to conduct this suitability practicable its preservation and use in been removed and another 123 miles are assessment were placed in the Times an unimpaired condition, and meets proposed for removal within the Standard Newspaper in Humboldt five wilderness character criteria: (1) Redwood Creek portion of the park. The County on December 7, 8 and 9, 2005, The earth and its community of life are 1999 Final General Management/ and in the Del Norte Triplicate, in Del untrammeled by humans, where General Plan and FEIS for Redwood Norte County on December 13, 14, and humans are visitors and do not remain; National and State Parks states that until 15, 2005. -

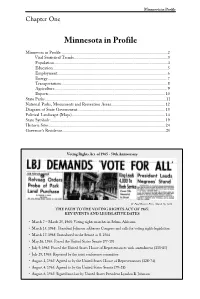

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14