THEOLOGIZING in the PHILIPPINES Insect REPORT ESTELA P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

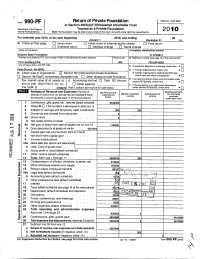

Form 990- PF Return of Private Foundation

of Private OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990- PF Return Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning , 2010 , and ending , 20 January 1 December 31 10 G Check all that apply: q Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity q Final return q Amended return q Address change q Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number Mustard Seed Foundation 57-074891 4 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see page 10 of the instructions) 7115 Leesburg Pike 304 703-524-5620 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application q is pending, check here ► Falls Church , VA 22043 D 1. Foreign q organizations, check here ► H Check type of organization. 21 Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and q q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation attach computation ► q E If private foundation status was terminated under I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method' Cash 0 Accrual section 507(b)(1)(A), q check here ► end of year (from Part II, col (c), q Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16) $ under section q ► 576087 (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis) 507(b)(1)(B), -

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

Open Educational Resources

C O L AND DISTANCE LEARNING AND DISTANCE PERSPECTIVES ON OPEN C O L PERSPECTIVES ON OPEN AND DISTANCE LEARNING PERSPECTIVES ON OPEN AND DISTANCE LEARNING OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES: AN ASIAN PERSPECTIVE Higher education has experienced phenomenal growth in all parts of Asia over the last two decades — from the Korean peninsula in the east to the western borders of Central Asia. This expansion, coupled with a diversity of delivery and technology options, has meant that more and more young Asians are experiencing tertiary education within their own countries. Open Educational Resources: An Asian Perspective Open Educational Resources: In South, South East and Far East Asia especially, universities, polytechnics, colleges and training institutes with a variety of forms, structures, academic programmes and funding provisions have been on an almost linear upward progression. Notwithstanding this massive expansion, equitable access is still a challenge for Asian countries. There is also concern that expansion will erode quality. The use of digital resources Open Educational is seen as one way of addressing the dual challenges of quality and equity. Open educational resources (OER), free of licensing encumbrances, hold the promise of equitable access to knowledge and learning. However, the full potential of OER is only realisable with greater Resources: An Asian knowledge about OER, skills to effectively use them and policy provisions to support their establishment in Asian higher education. This book, the result of an OER Asia research project hosted and implemented by the Wawasan Perspective Open University in Malaysia, with support from Canada’s International Development Research Centre, brings together ten country reports and ten case studies on OER in the Asian region that highlight typical situations in each context. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

Sustainable Smallholder Agriculture Clusters in the Philippines

Sustainable Smallholder Agriculture Clusters in the Philippines: Why do some fail while others survive? John Angus Oakeshott B.Sc. (Agr.), M.B.A. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Agriculture and Food Sciences i ii Abstract The important role and contribution of smallholder farmers (SHF) in the southern Philippines towards national food security and the fabric of the nation is without question. This study identified the priorities for a SHF collective action approach for sustainable livelihood improvement. These priorities developed into the Sustainable Agricultural Cluster Framework (SACF) that included the interactions, perturbations and transformational influences to describe the SHF collective approach. Since 2010 the Philippines has enjoyed an annual economic growth of over 6% in Gross Domestic Product (GDP); however, poverty and hunger persists and in some rural regions continues to worsen. The failure of GDP benefits reaching the vulnerable poor and influencing poverty puts more importance on policies to strengthen and enhance national food and nutritional security. An increasing population, lack of infrastructure, encroachment of global marketing, decaying resources, SHFs limited knowledge of marketing and production, and Climate Change threaten the development goals of the Government of the Philippines. These structural and natural disaster threats disproportionately affect the SHFs and other vulnerable poor. Rural projects and structural adjustment programs frequently focus on financial improvement and promotion of farming practices that integrate into an economically efficient conventional food system. Whilst providing long-term benefits to the national economy these transformational programs can impose economic hardships on SHFs, or worse a permanent collapse of their local food system as they embrace the global trade of the conventional food system. -

2007 Annual Report

2007 ANNUAL REPORT C1 “How shall we picture the kingdom of God? . It is like a mustard seed . ” —MARK 4:30-32 The Mustard Seed Foundation is a Christian family foundation established in 1983 under the leadership of Dennis W. Bakke and Eileen Harvey Bakke. The Foundation was created as an expression of their desire to be faithful stewards of the financial resources entrusted to them, to bring together the Christian members of their extended families into common ministry, and to advance the Kingdom of God. The Foundation provides grants to churches and Christian organizations worldwide that are engaged in Christian ministry including outreach, discipleship, and economic empowerment. The Foundation also awards scholarships to Christians pursuing advanced educational degrees in preparation for leadership roles in both the Church and society. All directors and staff of the Mustard Seed Foundation are committed followers of Jesus Christ and affirm the Lausanne Covenant. C2 Dear friends of the Mustard Seed Foundation, When we started the Foundation in 1984, we did not have Over 1,000 students attending Christ-centered colleges and a fully developed philosophy of giving that would guide this seminaries outside the United States received $1.5 million in organization into the future. We did surround ourselves with scholarships through our Theological Education program. people of faith from both the Bakke and Harvey families to Another 57 students enrolled at Bakke Graduate University help us discern what good stewardship meant. Over the years, (BGU) were awarded scholarships for their work toward a simple approach evolved. Doctorate or Masters degrees. Of these scholarships, 77% were awarded to students who live and minister outside the The resources entrusted to us don’t belong to us: God has called United States. -

1 Gender-Based Violence in 140 Characters Or Fewer

Gender-Based Violence in 140 Characters or Fewer: A #BigData Case Study of Twitter Hemant Purohit1,2, Tanvi Banerjee1,2, Andrew Hampton1,3, Valerie L. Shalin1,3, Nayanesh Bhandutia4 & Amit P. Sheth1,2 1Ohio Center of Excellence in Knowledge-enabled Computing (Kno.e.sis), Dayton, OH, USA 2Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA 3Department of Psychology, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA 4United Nations Population Fund Headquarters, NYC, NY, USA Corresponding Authors: Hemant Purohit, Amit Sheth, Valerie Shalin: {hemant, amit, valerie}@knoesis.org ABSTRACT Public institutions are increasingly reliant on data from social media sites to measure public attitude and provide timely public engagement. Such reliance includes the exploration of public views on important social issues such as gender-based violence (GBV). In this study, we examine big (social) data consisting of nearly fourteen million tweets collected from Twitter over a period of ten months to analyze public opinion regarding GBV, highlighting the nature of tweeting practices by geographical location and gender. We demonstrate the utility of Computational Social Science to mine insight from the corpus while accounting for the influence of both transient events and sociocultural factors. We reveal public awareness regarding GBV tolerance and suggest opportunities for intervention and the measurement of intervention effectiveness assisting both governmental and non-governmental organizations in policy development. Keywords: computational social science, gender-based violence, social media, citizen sensing, public awareness, public attitude, policy, intervention campaign 1 [1.] INTRODUCTION Gender-based violence (GBV), primarily against women, is a pervasive, global phenomenon affecting both developed and developing countries. -

Congregational Health Network Partner Congregations Unity Church of God in Christ Praise & Fellowship Pilgrim Rest Baptist M

Congregational Health Network Partner Congregations Unity Church of God in Christ C.M.E. Headquarters Praise & Fellowship Charity Outreach Ministries Pilgrim Rest Baptist Hill Chapel Missionary Baptist Magnolia 1st Baptist Historical First Baptist Oak Grove Baptist Alexander/Pleasant Grove UM Pentecostal MBC New Beginning Church Golden Leaf Baptist St. Jude Missionary Baptist Greater New Life Baptist Burdette United Methodist Faith Temple Ministries Higher Hope COGIC Fountain of Life The Mission Church Friendship UMC Freedom's Chapel Christian Georgian Hills Church of God Germantown UMC Gifts of Life Ministries Germantown Church of Christ Impact Baptist Wholeness in Christ Family Ministries Mt. Vernon UMC Millington 1st UMC Renewed Hope in Christ Ministries Holy Community UMC Centenary UMC Christ M.B. Church Macedonia Baptist Grace UMC Cross of Calvary Lutheran Fullview Baptist Union Valley Baptist Mississippi Boulevard Christian Mt.Calm Baptist 1st Baptist - Broad Mt. Vernon Baptist - Westwood New Bethel M.B. - Germantown Mt. Moriah Missionary Baptist Soul Winners Baptist New Highway C.O.G.I.C New Bethel M.B. - Stovall Whitehaven United Methodist Omega Church, Inc. Life Changing Word Ministries Redeemed Ministries Hearn Grove M.B. Testament of Hope Community Baptist Greater Imani Grace Temple Community Greater St. Thomas Open Heart Spiritual Center Finley Grove M.B. Oak Hill Baptist Faithful Believers United Ministries Mt. Zion Baptist New Nonconnah New Zion M.B. Church Castalia Baptist The Healing Center Full Gospel Baptist Brown Missionary Baptist North Star Community ******** Alcy Ball Road Community Church Covenant United Methodist Good Shepherd United Methodist Iglesia Luterana "El Mesias" 1st Baptist Scenic Hills United Methodist Morning View Baptist Tabernacle of Praise Baptist Liberty Hill M.B. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

THE SOCIAL MEDIA (R)EVOLUTION? Asian Perspectives on New Media

THE SOCIAL MEDIA (R)EVOLUTION? Asian Perspectives On New Media CONTRIBUTIONS BY: APOSTOL, AVASADANOND, BHADURI, NAZAKAT, PUNG, SOM, TAM, TORRES, UTAMA, VILLANUEVA, YAP EDITED BY: SIMON WINKELMANN Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Singapore Media Programme Asia The Social Media (R)evolution? Asian Perspectives On New Media Edited by Simon Winkelmann Copyright © 2012 by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6603 6181 Fax: +65 6603 6180 Email: [email protected] www.kas.de/medien-asien/en/ All rights reserved Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Layout and Design Hotfusion 7 Kallang Place #04-02 Singapore 339153 www.hotfusion.com.sg CONTENTS Foreword 5 Ratana Som Evolution Or Revolution - 11 Social Media In Cambodian Newsrooms Edi Utama The Other Side Of Social Media: Indonesia’s Experience 23 Anisha Bhaduri Paper Chase – Information Technology Powerhouse 35 Still Prefers Newsprint Sherrie Ann Torres “Philippine’s Television Network War Going Online – 47 Is The Filipino Audience Ready To Do The Click?” Engelbert Apostol Maximising Social Media 65 Bruce Avasadanond Making Money From Social Media: Cases From Thailand 87 KY Pung Social Media: Engaging Audiences – A Malaysian Perspective 99 Susan Tam Social Media - A Cash Cow Or Communication Tool? 113 Malaysian Impressions Syed Nazakat Social Media And Investigative Journalism 127 Karen Yap China’s Social Media Revolution: Control 2.0 139 Michael Josh Villanueva Issues In Social Media 151 Social Media In TV News: The Philippine Landscape 163 Social Media For Social Change 175 About the Authors 183 Foreword ithin the last few years, social media has radically changed the media Wsphere as we know it. -

Houston Church Listing

Houston Church Listing Church Address Phone 34th Temple Church Of God 1317 E 34th St, Houston, TX (713) 862-9423 A J Ford Ministries 1401 W Tidwell Rd, Houston, TX (713) 952-9335 A Safe Place Christian Ctr 11411 Homestead Rd, Houston, TX (281) 372-0500 Abiding Love Baptist Church 9135 Irvington Blvd, Houston, TX (713) 691-9135 Abiding Missionary Baptist Church 14145 Bridgeport Rd, Houston, TX (713) 433-2971 Abiding Word Lutheran Church 17123 Red Oak Dr, Houston, TX (281) 444-5894 Abundance Of Blessings Church 9311 Compton St, Houston, TX (713) 631-0005 Abundant Grace Parish 15825 Bellaire Blvd, Houston, TX (281) 933-5533 Abundant Harvest Church 8734 Windswept Ln, Houston, TX (713) 785-1756 Abundant Life Baptist Church 2411 W Little York Rd, Houston, TX (713) 263-1911 Abundant Life Cathedral 11300 Harwin Dr, Houston, TX (281) 983-8200 Abundant Life Christian Fllwsh 7114 Breen Dr, Houston, TX (281) 405-8123 Abundant Love Christian Ctr 14325 Crescent Landing Dr, Houston, TX (281) 990-9370 Abundant Love Ministries 4601 Yale St, Houston, TX (713) 691-3552 Abundant Waters Fellowship 17810 French Rd, Houston, TX (281) 859-7033 Acreage Home Church Of God 8211 W Montgomery Rd, Houston, TX (281) 447-5982 Addicks United Methodist Chr 1212 Highway 6 N, Houston, TX (281) 531-0550 Advent Lutheran Church 5820 Pinemont Dr, Houston, TX (713) 686-8201 African Apostilic Church 13180 Westpark Dr # 101a, Houston, TX (281) 589-2556 Agape Chinese Fellowship 12807 Lodenbriar Dr, Houston, TX (281) 933-4553 Agape Christian Ministries 9543 S Main St, Houston, TX -

Educommasia-2013-07.Pdf (2.220Mb)

Vol. 17 No. 3 July 2013 A Newsletter of the Commonwealth Educational Media Centre for Asia From Director’s Desk In this issue s we enter the Dhanarajan focusses on the need of quality OER, Guest Column 2 second year of which is also a theme of a book published by A CEMCA. In Case Study section, we present to Spotlight On 6 the current Three Year Plan (TYP) 2012-15, I have taken you the story of student support services at the Worth While Web 8 some time to reflect and Korean National Open University (KNOU). The review the past one year to spotlight section presents a landmark initiative by CEMCA News 9 understand how we implemented various the Government of India – the National Mission on Education through Information and Case Study 14 activities to reach the planned outcomes. On looking back, I feel satisfied to report our Communication Technology (NMEICT), which Regional Round Up 16 esteemed readers that we achieved almost all the has resulted in many successful developments, activities that we started to implement. Most of including the A-VIEW reviewed in the Software Book Review 17 these were possible because of the support we Review section. In the SMART Tips section, Dr. SMART Tips 19 received directly and indirectly from many of you. Kiron Bansal describes how the Community Radio We developed collaborative partnerships with stations can collect data and develop listeners’ Technology Tracking 21 many institutions in the region, notably the profile to support content development that are based on the needs of the listeners.