BLACK HOLES, WORMHOLES, and TIME-MACHINES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballard's Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity

Ballard's Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity Item Type Book Chapter Authors Wymer, Rowland Publisher Palgrave Macmillan Download date 04/10/2021 07:04:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/2384/295021 Pre-print copy. For the final version, see: Wymer, R. , 2012. ‘Ballard’s Story of O: “The Voices of Time” and the Quest for (Non)Identity’. In Jeannette Baxter and Rowland Wymer, eds. 2012. J. G. Ballard: Visions and Revisions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, ch. 1, pp. 19-34. Chapter One Ballard’s Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity Rowland Wymer ‘The Voices of Time’ (1960) is the finest of Ballard’s early stories, an enigmatic but indisputable masterpiece which marks the first appearance of a number of favourite Ballard images (a drained swimming-pool, a mandala, a collection of ‘terminal documents’) and prefigures the ‘disaster’ novels in its depiction of a compulsively driven male protagonist searching for identity (or oblivion) within a disturbingly changed environment. Its importance to Ballard himself was confirmed by its appearance in the title of his first collection of short fiction, The Voices of Time and Other Stories (1962), and by his later remark that it was the story by which he would most like to be remembered.1 It was first published in the October 1960 issue of the science fiction magazine New Worlds alongside more conventional SF stories by James White, Colin Kapp, E. C. Tubb, and W. T. Webb. This was three-and-a-half years before Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the magazine and inaugurated the ‘New Wave’ by aggressively promoting self- consciously experimental forms of speculative fiction. -

Sfi Welcomes the Livingston/Planthold Team!

SFI WELCOMES THE LIVINGSTON/PLANTHOLD TEAM! STARFLEET congratulates Mandi Livingston and her team for winning the 2004 Election for Commander, STARFLEET, and gives a warm welcome to our new Executive Committee and 126 staff members! DEC 2004/ Left: Sunnie Planthold, our new Vice JAN 2005 Commander, and our new Chief of Operations, Commodore Jack “Towaway” Eaton, at Vulkon in Orlando, Florida - where they receive the good news via cell phone! (In this photo, she knows, but he doesn’t - yet!) Photo submitted by Ralph Planthold Additional Vulkon photos on p. 28 TWO SETS OF NEWLYWEDS: JOAN & RICARDO BRUCKMAN... Last issue, we had one beautiful STARFLEET wedding... and this time, we have TWO to celebrate! Right: The happy couple, Joan and Ricardo Bruckman of the USS Hathor , pause for a group photo with too many STARFLEET members to name here (including members of the CQ team)! Photo submitted by Wade Olsen ...AND WENDY & JON LANE! Left: On September 5, Jon Lane and Wendy Stanford became married on a large green lawn situated along the edge of the beautiful and scenic bay at the Newport Dunes Resort. The audience included friends from the USS Angeles and STARFLEET members from both coasts. Photo submitted by Gary Sandridge Additional wedding photos on back cover USPS 017-671 112626 112626 STARFLEET Communiqué Jimmy Doohan’s Last Convention............3 Volume I, No. 126 Hollywood Entertainment Museum.........5 Inspired To Make A Difference..................6 Published by: Colorado SFI Member Goes Bald............6 STARFLEET, The International “Trekkies 2” Review.................................6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. Tuvok Does Astronomy............................7 3212 Mark Circle Jon Lane Gets Married............................7 Independence, MO 64055 From The Center Seat............................8 George “Sulu” Takei and USS Angeles CO Janice Willcocks. -

Nasa and the Search for Technosignatures

NASA AND THE SEARCH FOR TECHNOSIGNATURES A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop NOVEMBER 28, 2018 NASA TECHNOSIGNATURES WORKSHOP REPORT CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What are Technosignatures? .................................................................................................................................... 2 What Are Good Technosignatures to Look For? ....................................................................................................... 2 Maturity of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Breadth of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Limitations of This Document .................................................................................................................................... 6 Authors of This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 EXISTING UPPER LIMITS ON TECHNOSIGNATURES ....................................................................................................... 9 Limits and the Limitations of Limits ........................................................................................................................... -

Issue 349, April 2015

Sigma The Newsletter of PARSEC - www.parsec-sff.org April, 2015 - No. 349 PM. I arrive at about 12:30PM and will in the future President’s Capsule be there by Noon. The hour or so before the meeting It seems that spring has sprung. begins is a great time when people trickle in and talk Turns my head metaphorically spontaneously about what movies they have seen, and practically to re-creation. what books they are reading, what conventions and I’m not sure what clod put the be- shows they will attend. It is a wonderful time. I urge ginning of the year at frigid and fal- you to become part. low January, but it would have been I have seen some email from people who are Par- better done in April. Oh, if I’m ever by Joe Coluccio sec members living out of city and state who have re- emperor… quested audio or video of the meetings. There are So, what of SF in this “new” beginning? some problems with the idea. I will be glad to ask any It is harder than ever to bring to light new SF works of the guest speakers and others if they are willing to and new talent, what with everyone publishing every- be recorded. BUT. Video and/or audio takes equip- thing everywhere. I read all the mags both pro and not ment. I don’t perceive that as a real problem. I have and am amazed at the sheer vision exhibited on the enough audio equipment and can scrape together digital and print pages. -

Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A

“Oh, Awful Power”: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A. Gordon Submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Under the Executive Committee Of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Walter A. Gordon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “Oh, Awful Power”: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A. Gordon “‘Oh, Awful Power’: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature” analyzes the social and cultural meaning of energy through an examination of African American literature from the first half of the twentieth century—the era of both King Coal and Jim Crow. Situating African Americans as both makers and subjects of the history of modern energy, I argue that black writers from this period understood energy as a material substrate which moves continually across boundaries of body, space, machine, and state. Reconsidering the surface of metaphor which has masked the significant material presence of energy in African American literature— the ubiquity of the racialized descriptor of “coal-black” skin, to take one example—I show how black writers have theorized energy as a simultaneously material, social, and cultural web, at once a medium of control and a conduit for emancipation. African American literature emphasizes how intensely energy impacts not only those who come into contact with its material instantiation as fuel—convict miners, building superintendents—but also those at something of a physical remove, through the more ambient experiences of heat, landscape, and light. By attending to a variety of experiences of energy and the nuances of their literary depiction, “‘Oh, Awful Power’” shows how twentieth-century African American literature not only anticipates some of the later insights of the field now referred to as the Energy Humanities but also illustrates some ways of rethinking the limits of that discourse on interactions between energy, labor, and modernity, especially as they relate to problems of race. -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25 -

Climate Change in Fiction Master’S Thesis by Miglė Šaltytė

Università Ca' Foscari Venezia Climate Change in Fiction Master’s Thesis by Miglė Šaltytė Miglė Šaltytė 1-10-2019 Table of Contents Introduction........................................................................................................................................................2 1. Climate Fiction …………………………………….……………………….................................................5 2. “Serious” Climate-Change Fiction …………................................................................................................8 3. Artistically Compelling Climate-Change Fiction.........................................................................................11 4. What Climate-Change Fiction Reveals About Our Attitudes towards the Human and the Non-Human.…13 5. The Works Chosen and the Structure of the Thesis………………………………………………...….…..14 6. Truth, Politics, and Climate Change…..….......…………………………………………………….….…..15 6.1 Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver……………………………………………………………..…..16 6.2 The State of Fear by Michael Crichton………………………………………………………………..….20 6.3 Solar by Ian McEwan……………………………………………………………………………..………24 7. The Human Point of View in Climate-Chamage Fiction …………………………………………....…….30 7.1 “Shooting the Apocalypse” by Paolo Bacigalupi………………………………………………..………..31 7.2 “A Hundred Hundred Daisies” by Nancy Kress………………………………………………….………34 7.3 “The Mutant Stag at Horn Creek” by Sarah K. Castle……………………………………………..……..36 7.4 “The Tamarisk Hunter” by Paolo Bacigalupi…………………………………………………….………40 8. Climate Change on the Fringe of “Serious” Literature…………………………………………….………43 -

Technosignature Report Final 121619

NASA AND THE SEARCH FOR TECHNOSIGNATURES A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop NOVEMBER 28, 2018 NASA TECHNOSIGNATURES WORKSHOP REPORT CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 What are Technosignatures? .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 What Are Good Technosignatures to Look For? ....................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Maturity of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Breadth of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Limitations of This Document .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Authors of This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 EXISTING UPPER LIMITS ON TECHNOSIGNATURES ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Limits and the Limitations of Limits ........................................................................................................................... -

OPUNTIA of Giant Vehicles

THERE WERE GIANTS IN THE EARTH IN THOSE FUTURES by Dale Speirs While thinning out my library, I saw that I had a number of books on the theme OPUNTIA of giant vehicles. I’ve always been interested in the practical details of such vehicles. If a supervillain has his own personal giant submarine, how does he schedule his crews? How does he get them to keep their mouths shut? Drydocks for maintenance and repairs are not cheap. Somebody has to flush out the bilges or empty the garbage cans. One wonders about these things. 278 Middle June 2014 There Go The Ships: There Is That Leviathan. CV (1985, hardcover) by Damon Knight is about the Sea Venture, a giant Opuntia is published by Dale Speirs, Calgary, Alberta. Since you are reading floating city the size of eight ocean liners and nicknamed CV. It is a raft, has this only online, my real-mail address doesn’t matter. My eek-mail address (as no propulsive engines, and floats along the North Pacific Gyre. Half the the late Harry Warner Jr liked to call it) is: [email protected] population on board are permanent residents who provide the services for the When sending me an emailed letter of comment, please include your name and other half, the tourists. The CV is submersible and can sink down below town in the message. storms, an important point since it cannot maneuver on the surface. The corporation that owns CV is trying to make it self-sufficient, growing hydroponic vegetables on board, harvesting fish as it floats along, and scraping the bottom for minerals to bring in some cash income. -

Science Fiction Jack Kirby

The Science Fiction Work of Jack Kirby Adam McGovern with Randolph Hoppe Winter Con 3 December 2016 Queens, NYC From the Gutter… Jack Kirby famously had the course of his career set when a discarded science-fiction pulp — Wonder Stories — floated past him in a tenement gutter. This opened up both his future, and a lot of the world’s. Painting by Steve Rude Streetwise (Alternate), TwoMorrows Publishing, 2000 Painting by Steve Rude Streetwise, TwoMorrows Publishing, 2000 ...to the Cosmos! Painting by Frank Paul Wonder Stories, December 1932 Decades later, Kirby would speak of sensing the cosmos inside of him — for those of us who needed introducing, he would portray it for us in realms of the Marvel and DC universes that became signature territories in both those companies’ mythos. Detail from “Super War!” by Kirby, Colletta, Costanza, Serpe(?) Forever People 2, DC Comics, May 1971. Spread from “...And One Shall Save Him!” by Kirby, Lee, Sinnott, Rosen, Goldberg(?) Fantastic Four 62, Marvel Comics, May 1967. But even in the 1930s, he was reading as much science as science-fiction — as early as the underground hidden-society adventure Blue Bolt he and partner Joe Simon were imagining alternate dimensions, when physical space-travel was still a dawning fantasy for many. Page 5 from “Blue Bolt” by Kirby, Simon, Avison, Gabriele, Ferguson, ? Blue Bolt 5, Novelty Press, October 1940 Science was the source of many of Kirby’s most iconic heroes’ powers — perhaps most famously Captain America, accepting a super-serum that was like a magic potion for an era where the gods couldn’t necessarily be relied on. -

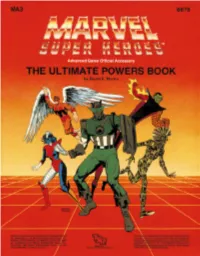

Ultimate Powers Book

RANGE TABLES Rank Range A Range B Range C Range D Range E Feeble Contact Contact 1 area 10 feet 2 miles Poor 1 area 1 area 10 areas 1 area 25 miles Typical 2 areas 5 areas 1 mile 4 areas 250 miles Good 4 areas 10 areas 3 miles 16 areas 2500 miles Excellent 6 areas 25 areas 6 miles 64 areas 25,000 miles Remarkable 8 areas 1 mile 12 miles 6 miles 250,000 miles Incredible 11 areas 2 miles 25 miles 250 miles 2.5 million miles Amazing 20 areas 3 miles 50 miles 1000 miles 25 million miles Monstrous 40 areas 6 miles 120 miles 4000 miles 250 million miles Unearthly 60 areas 10 miles 250 miles 16,000 miles 2.5 billion miles Shift X 80 areas 15 miles 500 miles 64,000 miles 25 billion miles Shift Y 160 areas 30 miles 1200 miles 250,000 miles 250 billion miles Shift Z 400 areas 50 miles 2500 miles 1 million miles 1/2 light year CL1000 100 miles 80 miles 5000 miles 4 million miles .5 light years CL3000 10,000 miles 150 miles 12,000 miles 16 million miles 50 light years CL5000 100,000 miles 250 miles 250,000 miles 64 million miles 500 light years AREA OF EFFECT Rank Name Radius (in feet) Area Volume Feeble 1 3 sq. ft. 3 cu. ft. Poor 2 12 sq. ft. 25 cu. ft. Typical 4 200 sq. ft. 200 cu. ft. Good 10 314 sq. ft. 3,140 cu. ft. Excellent 15 707 sq. -

Eclipse Maid

Eclipse Maid 1 Eclipse Maid Being a transhuman/post-cyberpunk hack for Maid RPG Work-in-progression version 0.18, updated 2015-02-09 Note: This document is a WORK IN PROGRESS, released for review and playtesting purposes only. Many elements are untested and/or incomplete. Credits Writer: David J Prokopetz <http://www.penguinking.com> Illustrator: Bryce Nakagawa <confact info here?> Contributors: Pneumonica <[email protected]> Teleute <http://www.obsidianportal.com/profile/Teleute> Author's Note Yes, the title and substantial chunks of the terminology are “borrowed” wholesale from Eclipse Phase. This author makes no apologies whatsoever. Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................1 Character Creation.............................................................1 Egos...................................................................................2 Ego Qualities Table.............................................................3 Morphs................................................................................6 Morph Qualities Table.......................................................12 Master Creation................................................................17 Introduction Posthuman Master Qualities Table...................................19 In the distant future, humanity's age has passed. Runaway Mansion Creation.............................................................20 technological development has led to the obsolescence of Special Facilities Table.....................................................22