The Middle Persian of Backgammon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

Enumerating Backgammon Positions: the Perfect Hash

Enumerating Backgammon Positions: The Perfect Hash By Arthur Benjamin and Andrew M. Ross ABSTRACT Like many games, people place money wagers on backgammon games. These wagers can change during the game. In order to make intelligent bets, one needs to know the chances of winning at any point in the game. We were working on this for positions near the end of the game when we needed to explicitly label each of the positions so the computer could refer to them. The labeling developed here uses the least possible amount of computer memory, is reasonably fast, and works well with a technique known as dynamic programming. INTRODUCTION The Game of Backgammon Backgammon is played on a board with 15 checkers per player, and 24 points (orga nized into four tables of six points each) that checkers may rest on. Players take turns rolling the two dice to move checkers toward their respective "home boards," and ulti mately off the board. The first player to move all of his checkers off the board wins. We were concerned with the very end of the game, when each of the 15 checkers is either on one of the six points in the home board, or off the board. This is known as the "bearoff," since checkers are borne off the board at each turn. Some sample bearoff posi tions are shown in Figure 1. We wanted to calculate the chances of winning for any arrangement of positions in the bearoff. To do this, we needed to have a computer play backgammon against itself, to keep track of which side won more often. -

Temporal Difference Learning Algorithms Have Been Used Successfully to Train Neural Networks to Play Backgammon at Human Expert Level

USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS (Under the direction of Khaled Rasheed) ABSTRACT Temporal difference learning algorithms have been used successfully to train neural networks to play backgammon at human expert level. This approach has subsequently been applied to deter- ministic games such as chess and Go with little success, but few have attempted to apply it to other nondeterministic games. We use temporal difference learning to train neural networks for four such games: backgammon, hypergammon, pachisi, and Parcheesi. We investigate the influ- ence of two training variables on these networks: the source of training data (learner-versus-self or learner-versus-other game play) and its structure (a simple encoding of the board layout, a set of derived board features, or a combination of both of these). We show that this approach is viable for all four games, that self-play can provide effective training data, and that the combination of raw and derived features allows for the development of stronger players. INDEX WORDS: Temporal difference learning, Board games, Neural networks, Machine learning, Backgammon, Parcheesi, Pachisi, Hypergammon, Hyper-backgammon, Learning environments, Board representations, Truncated unary encoding, Derived features, Smart features USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS B.S., Georgia Institute of Technology, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS,GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Glenn F. Matthews All Rights Reserved USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. -

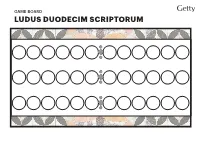

Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum Game Board Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum

GAME BOARD LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM GAME BOARD LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM L E V A T E D I A L O U L U D E R E N E S C I S I D I O T A R E C E D E This inscribed board says: “Get up, get lost. You don’t know how to play! Idiot, give up!” Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) xiv.4125 INFORMATION AND RULES LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM ABOUT Scholars have reconstructed the direction of play based on a beginner’s board with a sequence of letters. Roland Austin and This game of chance and strategy is a bit like Backgammon, and it Harold Murray figured out the likely game basics in the early takes practice. The game may last a long time—over an hour. Start to twentieth century. Rules are adapted from Tabula, a similar game play a first round to learn the rules before getting more serious—or before deciding to tinker with the rules to make them easier! WHAT YOU NEED We provide two boards to choose from, one very plain, and another • 2 players with six-letter words substituted for groups of six landing spaces. • A game board with 3 rows of 12 game spaces (download and print Romans loved to gamble, and some scholars conjecture that ours, or draw your own) Duodecim boards with writing on them were intended to disguise their • 5 flat identifiably different game pieces for each player. They will be function at times when authorities were cracking down on betting. stacked. Pennies work: heads for one player, tails for the other Some boards extolled self-care, Roman style; one says: “To hunt, to • You can also print and cut out our gaming pieces and glue them to bathe, to play, to laugh, this is to live!” Another is a tavern’s menu: pennies or cardboard “We have for dinner: chicken, fish, ham, peacock.” But some boards • 3 six-sided dice are too obvious to fool anyone. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

1 SASANIKA Late Antique Near East Project -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

SASANIKA Late Antique Near East Project SASANIKA PROJECT: by Touraj Daryaee, California State University, Fullerton ADVISORY BOARD Kamyar Abdi, Dartmouth College Michael Alram, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Daryoosh Akbarzadeh, National Museum of Iran Parissa Andami, Money Museum, Tehran Bahram Badiyi, Brooks College Carlo G. Cereti, University of Rome Erich Kettenhofen, University of Trier Richard N. Frye, Harvard University Mohammad Reza Kargar, National Museum of Iran Judith Lerner, Independent Scholar Maria Macuch, Free University of Berlin Michael G. Morony, University of California, Los Angeles Antonio Panaino, University of Bologna James Russell, Harvard University A. Shapur Shahbazi, Eastern Oregon University Rahim Shayegan, Harvard University P. Oktor Skjærvø, Harvard University Evangelos Venetis, University of Edinburgh Joel T. Walker, University of Washington Donald Whitcomb, University of Chicago ADVISORY COMMITTEE Ali Makki Jamshid Varza WEBSITE COORDINATORS Haleh Emrani Khodadad Rezakhani 1 One of the most remarkable empires of the first millennium CE was that of the Sasanian Persian Empire. Emanating from southern Iran’s Persis region in the third century AD, the Sasanian domain eventually encompassed not only modern day Iran and Iraq, but also the greater part of Central Asia and the Near East, including at times, the regions corresponding to present-day Israel, Turkey, and Egypt. This geographically diverse empire brought together a striking array ethnicities and religious practices. Arameans, Arabs, Armenians, Persians, Romans, Goths as well as a host of other peoples all lived and labored under Sasanian rule. The Sasanians in fact established a relatively tolerant imperial system, creating a vibrant communal life among its Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian citizens. This arrangement which allowed religious officials to take charge of their own communities was a model for the Ottoman millet system. -

Magriel Cup Tourney of Stars

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE USBGF FALL 2020 Magriel Tourney Cup of Stars USA Defeats UK Honoring our in Backgammon Founding Sponsors Olympiad U.S. BACKGAMMON FEDERATION VISIT US AT USBGF.ORG ABT Online! October 8 - 11, 2020 Columbus Day Weekend • Sunny Florida Warm-Ups, Thursday evening October 8 • Major Jackpots - Friday afternoon October 9 • Special Jackpots: Women’s, Rookies, Super Seniors • Miami Masters (70+), FTH Board event • Orlando Open • Art Benjamin – the • Lauderdale Limited Mathemagician - seminar • Doubles – Friday evening • USBGF membership required • ABT Main divisions – starting • 100% return on entry fees Saturday, October 10 (ranging from $25 to $100) • Open/Advanced - Double elimination • $30 tournament fee • Last Chance fresh draw – • Trophies Sunday October 11 • Zoom Welcome Ceremony and Awards Ceremony See website for details: sunnyfl oridabackgammon.com USBGF A M E R I C A N BACKGAMMON TOUR #2020 Good Luck to Team USA in the WBIF Online Team Championship 2020 Congratulations to Wilcox Snellings, Bob Wachtel, Joe Russell (captain), Frank Raposa, Frank Talbot, and Odis Chenault for qualifying for Team USA! Follow Team USA on the World Backgammon Internet Federation website: https://wbgf.info/wbif-2/ California State Championship December 3 –6 2020 Register now: www.GammonAssociatesWest.com ONLINE! BACKGAMMON TOUR #2020 2 USBGF PrimeTime Backgammon Magazine Editor’s Note Fall 2020 Marty Storer, Executive Editor n this issue, replete with great photos, we continue to track online backgammon in America and all over the world. The veteran American grandmaster Chris Trencher appears on our cover following a great performance in the first Magriel Cup, Ia monumental U.S. -

The Games of Chess and Backgammon in Sasanian Persia

The Games of Chess and Backgammon in Sasanian Persia Touraj Daryaee California State University, Fullerton ﺁﺳﻤﺎن ﺗﺨﺘﻪ واﻧﺠﻢ ﺑﻮدش ﻡﻬﺮﻩ ﻧﺮد ﮐﻌﺒﺘﻴﻨﺶ ﻡﻪ وﺥﻮرﺷﻴﺪ وﻓﻠﮏ اﺳﺘﺎد اﺳﺖ ﺑﺎﭼﻨﻴﻦ ﺗﺨﺘﻪ و ایﻦ ﻡﻬﺮﻩ و ایﻦ ﮐﻬﻨﻪ ﺣﺮی ﻓﮑﺮﺑﺮدن ﺑﻮدت ، ﻋﻘﻞ ﺗﻮﺑﯽ ﺑﻨﻴﺎداﺳﺖ ﺷﺮط درﺁﻡﺪﮐﺎراﺳﺖ ﻧﻪ داﻧﺴﺘﻦ ﮐﺎر ﻃﺎس ﮔﺮﻧﻴﮏ ﻧﺸﻴﻨﺪ هﻤﻪ ﮐﺲ ﻧﺮاد اﺳﺖ Board games were played in many parts of the ancient world and so it is very difficult to attribute the origin of any board game to a particular region or culture. Board games have been found in ancient Mesopotamia, the oldest from the city of Ur, but one must also mention the game of Senet in ancient Egypt.1 Often board games were placed in the tombs of the Pharaohs and sometimes the dead are shown playing with the gods, for example one scene shows Rameses III (c. 1270 B.C.) playing with Isis to gain access to the nether world. The importance of this fact is we can see that early on some board games had cosmological and religious significance and were not just games played for pleasure. Reference to board games in Persia can be found as early as the Achaemenid period, where according to Plutarch a board game with dice was played by Artaxerxes.2 There is also a reference to a board game being played in 1For the Egyptian game of Senet see E. B. Pusch, Das Senet-Brettspiel im alten Aegypten, Muenchner aegyptologische Studien, Heft 38, Muenchen, Berlin, Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1979; W. Decker, Sports and Games of Ancient Egypt, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1992. -

How to Become a Backgammon Hog by Stefan Gueth

How to become a Backgammon Hog by Stefan Gueth: BEGINNER SECTION What Is Backgammon? by Michael Crane, BiBa Great Britain Backgammon is a combination of games; it is a race game as in ludo in that the first player to get all his men around the board and off is the winner; it is a strategy game as in chess because it isn't just a simple race around the board but an absorbing tactical manoeuvre around the board, during which you have to have alternative plans as present ones fall apart on the roll of a die; and it is a board game similar to draughts inasmuch as the checkers are the same shape and move in opposing directions. Summed up, backgammon is an exciting game of tactics, probabilities and chance. A game where, despite the vagaries of the dice, the more experienced and knowledgeable player will prevail in the long run. However, due to the chance or luck element, absolute beginners can on occasions triumph over a champion - this is the appeal of backgammon. Where Do We Start? - At The End! If I start at the beginning you won't have the faintest idea of what you're trying to achieve during a game of backgammon. It is much easier to explain how the game ends first - this way, when you start to play from the beginning you'll know exactly what is required to win - and how easy it can be to lose! The winner in backgammon, as in ludo, is the first person to get all their checkers (referred to as men) around the board and off; essentially a racing game. -

An Artificial Intelligence Approach to the Game of Backgammon

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 1-1-1983 An Artificial Intelligence Approach to the Game of Backgammon Chang-Chung Yang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Yang, Chang-Chung, "An Artificial Intelligence Approach to the Game of Backgammon" (1983). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of 7echnology Colle~e of Applied Science and Technology AN ARTIFICIAL I~TEIIIGENCE APPiOACH TO THE GAME OF EACKGAM~ON A thesis sut~itted in partial fulfillment of the Mister of Science in Co~puter Science Degree Program ty CEANG-CBUNG YANG A~Frcved ty: January, 1983 1 ACKNO~LEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Mr. Al Eiles, for the directing nd leading me on this project. I woild also like to thank Dr. Peter Lutz or the time he has spent as a ~ember of my committee. I would like to th- nH Mr. ~arren Carithers for the suggestion and encouragement. linal11, I ould like tc thamk my wife, Joy, for her help and support durinr the evolu ion of this kroject. Chang-Chung Yang I prefer to be contacted each time a request for reproduction is made. I can bE reached a t the following addre ss. _26_c2. __ ~~i? _-b_:'::::'"- __ 1.r_. __ R. ~~ye Y(Yf'P J:: TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Plakoto Board Game Strategy (2017) by John Mamoun Or, for Some Articles on Neural Nets and Plakoto Game Programming and Strategy, See

Plakoto A Backgammon Board Game Variant Introduction, Rules and Basic Strategy (by J.Mamoun - This primer is copyright-free, in the public domain) Introduction: Plakoto is a variation of the game of backgammon. Plakoto is played in Greece and Turkey, and in Egypt, where it is known as Mahbooseh. The greeks have a word called “Tavli,” which means the three backgammon games of backgammon, plakoto, and another game called fevga. The Greeks play these three games back to back in a kind of tavli “marathon” among friends in gatherings or coffee shops. In plakoto, unlike in backgammon, a checker cannot be hit and sent to the bar. Instead, in plakoto, a checker can be blocked if an opponent lands on the position point where that checker is located, but only if that checker is only one lonely checker (known as a blot) on that position point when the opponent lands on that checker. If the opponent lands on that checker, the opponents checker is laid on top of that checker on that position point. A player cannot move a trapped checker until all opponent checkers have moved off that trapped checker. An opponent can pile as many checkers as the opponent wants on the player's trapped checker. Players can form blocks by piling two of the same player's checkers on one position point, or players can form blocks by trapping an opponent checker on a position point. A player's block cannot be landed on by the opponent, and vice versa. Blocks are how players can slow down their opponents.