History Infirmary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

901, 904 906, 907

901, 904, 906 907, 908 from 26 March 2012 901, 904 906, 907 908 GLASGOW INVERKIP BRAEHEAD WEMYSS BAY PAISLEY HOWWOOD GREENOCK BEITH PORT GLASGOW KILBIRNIE GOUROCK LARGS DUNOON www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk Dunoon - Largs - Gourock - Greenock - Glasgow 901 906 907 908 1 MONDAY TO SATURDAY Code NS SO NS SO NS NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO NS SO Service No. 901 901 907 907 906 901 901 906X 906 906 906 907 907 906 901 901 906 908 906 901 906 Sandbank 06.00 06.55 Dunoon Town 06.20 07.15 07.15 Largs, Scheme – 07.00 – – Largs, Main St – 07.00 07.13 07.15 07.30 – – 07.45 07.55 07.55 08.15 08.34 08.50 09.00 09.20 Wemyss Bay – 07.15 07.27 07.28 07.45 – – 08.00 08.10 08.10 08.30 08.49 09.05 09.15 09.35 Inverkip, Main St – 07.20 – 07.33 – – – – 08.15 08.15 – 08.54 – 09.20 – McInroy’s Point 06.10 06.10 06.53 06.53 – 07.24 07.24 – – – 07.53 07.53 – 08.24 08.24 – 09.04 – 09.29 – Gourock, Pierhead 06.15 06.15 07.00 07.00 – 07.30 07.30 – – – 08.00 08.00 – 08.32 08.32 – 09.11 – 09.35 – Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.10 07.10 07.35 07.40 07.40 07.47 07.48 08.05 08.10 08.10 08.20 08.44 08.44 08.50 09.21 09.25 09.45 09.55 Greenock, Kilblain St 06.24 06.24 07.12 07.12 07.40 07.40 07.40 07.48 07.50 – 08.10 08.12 08.12 08.25 08.45 08.45 08.55 09.23 09.30 09.45 10.00 Port Glasgow 06.33 06.33 07.22 07.22 07.50 07.50 07.50 – 08.00 – 08.20 08.22 08.22 08.37 08.57 08.57 09.07 09.35 09.42 09.57 10.12 Coronation Park – – – – – – – 07.58 – – – – – – – – – – – – – Paisley, Renfrew Rd – 06.48 – – – – 08.08 – 08.18 – 08.38 – – 08.55 – 09.15 09.25 – 10.00 10.15 10.30 Braehead – – – 07.43 – – – – – – – – 08.47 – – – – 09.59 – – – Glasgow, Bothwell St 07.00 07.04 07.55 07.57 08.21 08.21 08.26 08.29 08.36 – 08.56 08.55 09.03 09.13 09.28 09.33 09.43 10.15 10.18 10.33 10.48 Buchanan Bus Stat 07.07 07.11 08.05 08.04 08.31 08.31 08.36 08.39 08.46 – 09.06 09.05 09.13 09.23 09.38 09.43 09.53 10.25 10.28 10.43 10.58 CODE: NS - This journey does not operate on Saturdays. -

Report for the Follow-Up Study

Health and Safety Executive A further study of cancer among the current and former employees of National Semiconductor (UK) Ltd., Greenock 20030.01 cover final.indd 1 8/16/10 4:17:07 PM A further study of cancer among the current and former employees of National Semiconductor (UK) Ltd., Greenock Health and Safety Executive and Institute of Occupational Medicine United Kingdom Andrew Darnton1, Sam Wilkinson1, Brian Miller2, Laura MacCalman2, Karen Galea2, Amy Shafrir2, John Cherrie2, Damien McElvenny3, John Osman1 1Health and Safety Executive Epidemiology Unit Redgrave Court Merton Road Bootle Merseyside L20 7HS 2Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Avenue North Riccarton Edinburgh EH14 4AP 3University of Central Lancashire School of Public Health and Clinical Sciences Preston Lancashire PR1 2HE © Crown copyright 2010 First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: The Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Current and former management and workers at NSUK Greenock without whom this investigation could not have been completed, especially Susan Seutter, Bob Steel, and Douglas Blackwood. Steering Committee Members, Raymond Agius, Freda Alexander and Oliver Blatchford. Dr Rod Muir, former chair of the Privacy Advisory Committee, NHS National Services, Scotland. Staff at NHS National Services, Scotland, Information and Statistics Division (ISD), especially Roger Black, David Brewster, Laura Kelso, Susan Frame, Judith Stark, Richard Dobbie, Lesley Bhatti, David Clark, Douglas Clark, Susan Jensen, and Catherine Storey. -

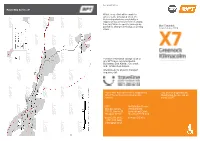

Provided Please Contact: SPT Bus Operations 131 St. Vincent St

Ref. W065E/07/19 Route Map Service X7 Whilst every effort will be made to adhere to the scheduled times, the Partnership disclaims any liability in respect of loss or inconvenience arising from any failure to operate journeys as Bus Timetable published, changes in timings or printing From 14 July 2019 errors. For more information visit spt.co.uk or any SPT travel centre located at Buchanan, East Kilbride, Greenock and Hamilton bus stations. Alternatively, for all public transport enquiries, call: If you have any comments or suggestions This service is operated by about the service(s) provided please McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on contact: behalf of SPT. SPT McGill’s Bus Service Bus Operations 99 Earnhill Rd 131 St. Vincent St Larkfield Ind. Estate Glasgow G2 5JF Greenock PA16 0EQ t 0345 271 2405 t 08000 515 651 0141 333 3690 e [email protected] Service X7 Greenock – Kilmacolm Operated by McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on behalf of SPT Route Service X7: From Greenock, Kilblain Street, via High Street, Dalrymple Street, Rue End Street, Main Street, East Hamilton Street, Port Glasgow Road, Greenock Road, Brown Street, Shore Street, Scarlow Street, Fore Street, Greenock Road, Glasgow Road, Clune Brae, Kilmacolm Road, Dubbs Road, Auchenbothie Road, Marloch Avenue, Kilmacolm Road, A761, Port Glasgow Road, to Kilmacolm Cross. Return from Kilmacolm Cross via Port Glasgow Road, A761, Kilmacolm Road, Marloch Avenue, Auchenbothie Road, Dubbs Road, Kilmacolm Road, Clune Brae, Glasgow Road, Greenock Road, Fore Street, Scarlow Street, Shore Street, Brown Street, Greenock Road, Port Glasgow Road, East Hamilton Street, Main Street, Rue End Street, Dalrymple Street, High Street to Greenock, Kilblain Street Monday to Saturday Greenock, Kilblain Street 1800 1900 2000 2100 ... -

The Early Annals of Greenock. Byby Archibald Brown Author of “Memorials of Argyllshire”

Archibald Brown – The Early Annals of Greenock – Published 1905 This download text is provided by the McLean Museum and Art Gallery, Greenock - © 2009 The Early Annals of Greenock. byby Archibald Brown author of “Memorials of Argyllshire” Greenock Telegraph printing works, Sugarhouse Lane. 1905 CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Greenock: Its Name and Place. CHAPTER II. The Early Heirs of Greenock. Section 1.—The Galbraiths of Greenock. 2.—The Crawfurds of Loudoun and their titles to Easter Greenock. 3.—Charter to Crawfurds of Easter Greenock. 4-—Ratification of Easter Greenock to Crawfurd of Kilbirney. 5.—Sale of Easter Greenock by Lady Crawfurd to Crawfurd of Carsburn and Sir John Shaw of Wester Greenock. CHAPTER III. The Old Landmarks of Easter Greenock. Section 1.—The Old Castle. 2.—Crawfurdsdyke and Harbour. CHAPTER IV. The Celebrities of Easter Greenock. Section 1.—John Spreull. 2.—The Watts. 3.—Jean Adam. 4-—Neil Dougal. CHAPTER V. The Genealogy of the Shaws of Wester Greenock and Sauchie. CHAPTER VI. The rule of the Shaws during the Barony and Charters. CHAPTER VII. The Causes of the Rise and Progress of the Town of Greenock. Section 1.—The Herring Trade. 2.—Greenock's Trade Connection with Glasgow. CHAPTER VIII. The Celts or Gaelic-speaking People in General, and the Highlanders of Greenock in Particular. Section 1.—Enquiry as to their Origin. 2.—Gaelic Speech in West of Scotland. 3.—Feudalism Introduced. 4.—Origin and Effects of the Highland Clan system. 5.—Highland Migration to Greenock. 6.—Natives of Greenock in 1792. CHAPTER IX. Appendices. Arms of Greenock. Cross of Greenock. -

Paisley and Clyde Cycling Path

Part of the This route is a partnership between National Cycle Network This 20 mile cycleway and footpath forms part of the Clyde to Forth National Cycle Route. It starts at Paisley Canal Railway Station, and ends in Gourock at the Railway Station and ferry terminal. Along the way it passes the town of Johnstone and crosses attractive open country between Bridge of Weir and Kilmacolm, before reaching Port Glasgow and Greenock on the Firth of Clyde. manly' traffic-free path far cyclists Ferries ply between Gourock and Duncan, a gateway to the The National Cycle Network is a comprehensive network Argyll area of the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs of safe and attractive routes to cycle throughout the UK. National Park. The route is mainly traffic-free apart from 10,000 miles are due for completion by 2005, one third of which will be on traffic-free paths, the rest will follow quiet short sections through Elderslie and kilmalcolm . There are lanes or traffic-calmed roads. It is delivered through the some steep gradients in Port Glasgow and Greenock . policies and programmes of over 450 local authorities and There is wheelchair access to the whole route. other partners, and is co-ordinated by the charity Sustrans. Sustrans - the sustainable transport charity - works on practical projects to encourage people to walk, cycle and www.nationalcyclenetwork.org.uk use public transport in order to reduce motor traffic and its adverse effects. 5,000 miles of our flagship project, the For more information on routes in your area: National Cycle Network, were officially opened in June 0845 113 0065 2000, we will increase this to 10,000 miles by 2005. -

Headington, Bridge of Weir

M209 Headington, Bridge of Weir Introduction This large, L-shaped, roughcast detached house with curved gabled dormers derived from 17th-century Scottish vernacular architecture, is located in the affluent Renfrewshire commuter village of Bridge of Weir. It was built for Alfred Allison Todd, partner in Dunn & Todd, a Glasgow firm of chartered accountants. Authorship: Drawings showing a slightly different treatment of the house were in Mackintosh's possession at the time of his death, and suggest that he contributed to an early stage of the design process. The plan, materials and historical references have parallels with Windyhill and The Hill House, but the house was built according to drawings signed by John Keppie, and it seems likely that Keppie had overall control of the design. Alternative names: Easter Hill; Easterhill. Cost from job book: £2899 4s 8d Status: Standing building Current name: Easterhill Current use: Residential (2014) Listing category: B: Listed as 'Easterhill' Historic Scotland/HB Number: 12775 RCAHMS Site Number: NS36SE 74 Grid reference: NS 39620 64997 Chronology 1902 April: Earliest date on drawings submitted to County of Renfrew Second or Lower District Master of Works department. 1 8 May: Contractor tenders accepted. 2 14 May: Application to build submitted to County of Renfrew Second or Lower District. 3 13 June: Plans approved by County of Renfrew Second or Lower District. 4 1905 20 April: Final payments to main contractors. 5 Description Origin and names Alfred Todd commissioned John Honeyman & Keppie to design a cottage at Bridge of Weir in 1898. However, that project appears to have been abandoned following the tendering process. -

View Timetable

SUMMER TIMETABLE FROM 3 APRIL 2017 Largs GLASGOW BRAEHEAD GREENOCK PORT GLASGOW GOUROCK INVERKIP 901, 904 WEMYSS BAY LARGS 906, 907 DUNOON www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk Dunoon - Largs - Gourock - Greenock - Glasgow 901 906 907 1 MONDAY TO FRIDAY from 3rd April 2017 Service No. 901 907 901 907 906 901 907 906X 906 901 906 907 901 906 901 906 901 906 901 906 901 Dunoon – – – – – – 07.01 – – – – 08.01 – – – – – – – – – Dunoon, John Street at Morrisons – – – – – – 07.03 – – – – 08.03 – – – – – – – – – Marine Parade at Kirn Church – – – – – – 07.08 – – – – 08.08 – – – – – – – – – Hunter’s Quay – – – – – – 07.20 – – – – 08.20 – – – – – – – – – Largs, Douglas Street – – – – – – – 07.03 – – – – – – – – – – – – – Largs Station – – – – 06.45 – – 07.15 07.30 07.45 08.05 – 08.15 08.30 08.40 09.00 09.10 09.30 09.40 10.00 10.10 Wemyss Bay – – – – 07.00 – – 07.30 07.45 08.00 08.20 – 08.30 08.45 08.55 09.15 09.25 09.45 09.55 10.15 10.25 Inverkip, Main Street – – – – 07.05 – – – 07.50 08.05 08.25 – 08.35 08.50 09.00 09.20 09.30 09.50 10.00 10.20 10.30 McInroy’s Point 05.56 06.25 06.35 06.55 – 07.20 07.43 – – 08.13 – 08.43 08.43 – 09.08 – 09.38 – 10.08 – 10.38 Gourock Station 06.01 06.30 06.40 07.00 – 07.25 07.49 – – 08.20 – 08.49 08.50 – 09.15 – 09.45 – 10.15 – 10.45 IBM – – – – 07.10 – – 07.36 07.58 – 08.33 – – 08.58 – 09.28 – 09.58 – 10.28 – Greenock Bus Station 06.10 06.40 06.55 07.10 07.25 07.40 08.00 07.50 08.15 08.35 08.50 09.03 09.05 09.15 09.30 09.45 10.00 10.15 10.30 10.45 11.00 Port Glasgow, Church Street 06.20 06.52 07.07 07.22 07.37 07.52 08.12 – -

Robert Steele and Company: Shipbuilders of Greenock

ROBERT STEELE AND COMPANY: SHIPBUILDERS OF GREENOCK Mark Howard There is a long tradition of shipbuilding on the west coast of Scotland. It began with the production of small fishing boats and coasters to satisfy the demand for vessels from people living in the region. The scale of production, however, was modest and might have remained so but for a number of changes taking place in the wider world. Foremost among these was the expansion of Britain's colonial empire, especially the plantations founded in the West Indies and North America.1 The efforts to establish and protect these colonies together with the trade they generated created a demand for new shipping that Scottish yards helped to satisfy. Other relevant factors were the frequent wars between 1750 and 1816 that helped keep ocean freight rates at high levels; the early stirrings of the industrial revolution; the influence of the Navigation Acts; and Britain's continuing naval dominance. The size of the United Kingdom's registered merchant fleet doubled between 1775 and 1790 following the American War of Independence, and by the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars had doubled again to 2,417,000 tons.2 Of particular importance to Scotland was the 1707 Act of Union that enabled her to share fully in Britain's economic growth, and the completion of the Clyde-Forth canal in 1790 that linked western and eastern Scotland and gave Glasgow better access to the Baltic trade. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, Scotland entered a period of rapid economic gTowth that was soon matched by a rise in trade. -

Birdwatching in Ayrshire and Arran

Birdwatching in Ayrshire and Arran Note on the on-line edition: The original leaflet (shown on the right) was published in 2003 by the Ayrshire Branch of the SOC and was so popular that the 20,000 print run is now gone. We have therefore published this updated edition on-line to ensure people interested in Ayrshire’s birds (locals and visitors) can find out the best locations to watch our birds. To keep the size of the document to a minimum we have removed the numerous photographs that were in the original. The on- line edition was first published in November 2005. Introduction This booklet is a guide to the best birding locations in Ayrshire and Arran. It has been produced by the Ayrshire branch of the SOC with help from individuals, local organisations and authorities. It should be used in conjunction with our website (www.ayrshire-birding.org.uk) which gives extra details. Additions and corrections can be reported via the website. The defining influences on Ayrshire as an environment for birds and other wildlife are its very long coast-line (135km not counting islands), and the fact that it lies almost entirely in the rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault and the Southern Upland Fault. Exceptions to this generally lowland character are the mountains of north Arran, our own little bit of the Highlands, and the moorlands and hills of the south and south-east fringes of the county. The mild climate has resulted in a mainly pastoral agriculture and plenty of rivers and lochs, making it good for farmland and water birds. -

Bridge of Weir — the Railway Brian Turner

RLHF Journal Vol.11 (2001/2) 1. Bridge of Weir — The Railway Brian Turner Introduction: It is quite apparent that the coming of the railway not only significantly enhanced the importance of Bridge of Weir, but also had a profound effect on the topography of the core of the village, as we shall see when we examine the construction work involved in creating it. Furthermore, in the present day and age, when railways over the whole of mainland Europe and the UK are undergoing a renaissance, being increasingly seen as the answer to excessive use of car transport and juggernaut long-distance haulage, it is noteworthy that the initiative for the first railway from Bridge of Weir came from within the community. This happened, of course, in the so-called ‘age of railway mania’, when railways were springing up all over the place connecting adjacent communities and ones farther apart. Historical: The earliest proposed scheme for a railway dates from 1845. The ambitious scheme was aimed at linking Johnstone, Houston, Bridge of Weir, and Port Glasgow; but it foundered through problems with finance and was abandoned. Not until 1861 did a group of local businessmen, landed gentry, and men of letters get together and successfully promulgate the idea of a railway to connect Bridge of Weir with the ‘outside world’. At that time the gateway to the outside world was seen as Johnstone, from where trains could be taken to Glasgow (eastwards) and Carlyle. Even London could be reached (westwards via Dalry and Kilmarnock). So it was that the ‘Bridge of Weir Railway Act’ of 1862 was passed, with an arrangement for the G&SWR to work the line. -

Hutcheson's Greenock Register, Directory and General Advertiser

GREENOCK PUBLIC LIBRARIES 111 REFERENCE DEPARTMENT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/hutchesonsgreeno184142uns HUTCHESON'S HREENOCK REGISTER DIRECTORY, AND GENERAL ADVERTISER, FOR 1841-42. GREENOCK : PRINTED BY JOHN MALCOM, 3ROAD CLOSE. 1841. ADDRESS. The design of the present work being to give a succinct and accurate Di= rectory of the bankers, merchants, manufacturers, ship-owners, agents, and principal inhabitants of Greenock, no pains have been spared to render it as correct and complete as possible. A short Historical Sketch has been prefixed, giving a concise view of the rise and progress of the town, with its harbours, commerce and manu- factures, together with the principal causes that have promoted its present maritime importance and manufacturing enterprise. In order to render the work as generally useful as possible, a Register has also been prefixed, forming a complete arrangement of corporate bodies, public institutions, religious associations, liteiary, scientific and other societies, to- gether with copious shipping and other lists connected with the town. In procuring the various details, the Publisher has availed himself of every means of information in his power. To the magistrates, the clergy, merchants, ship-owners^ and office-bearers of public institutions, he offers his respectful thanks for their obliging and valuable assistance. To Weir's History of Greenock, and to the columns of the Greenock Advertiser, he is also indebted, and acknowledges the free use he has made of the informa- tion contained in these publications. In a word, the Register and Directory may be briefly described as a com- pendious digest of the statistical, the moral, the political, and the commercial interests of the town of Greenock CONTENTS. -

Extra Clyde Sailings

Extended Clyde 2021 Sailings by Paddle Steamer Waverley August 23 to September 19 MONDAYS TUESDAYS THURSDAYS August 23 September 7 & 14 August 26 & September 9 Glasgow 0900 Glasgow 1015 Greenock 1050 Largs 1200 Greenock 1200 Kilcreggan 1115 Millport (Keppel) 1225 Largs 1330 Largs 1245 Lochranza 1340 Rothesay 1420 Millport (Keppel) 1310 Campbeltown 1520/1650 Cruise Kyles of Bute Brodick 1420/1430 Lochranza 1835 Rothesay 1620 Cruise to Pladda Millport (Keppel) 1950 Greenock 1800 & Round Holy Isle Largs 2015 Glasgow C Arr 1845 Brodick 1650/1700 Glasgow C Arr 2130 Largs 1915 Millport (Keppel) 1805 Largs 1835 August 30 WEDNESDAYS Kilcreggan 1945 Summer Bank Holiday August 25 to Greenock 2005 Glasgow 1100 September 15 Greenock 1245 Glasgow* 0900 September 2 & 16 Kilcreggan 1310 Largs 1145 Greenock 1050 Dunoon 1340 Rothesay 1235 Dunoon 1125 Cruise Loch Long Tighnabruaich 1325 Largs 1245 & Loch Goil Tarbert 1430 Millport (Keppel) 1310 Dunoon 1550 Cruise Loch Fyne Brodick 1420/1430 Kilcreggan 1615 towards Ardrishaig Cruise to Pladda Greenock 1640 Tarbert 1620 & Round Holy Isle Glasgow 1815 Tighnabruaich 1730 Brodick 1650/1700 Rothesay 1825 Millport (Keppel) 1805 TUESDAY Largs 1915 Largs 1835 August 24 Glasgow* C Arr 2015 Dunoon 1935 Largs 1130 *Sailing from Glasgow Greenock 2005 Dunoon 1230 September 1 only Greenock 1320 Kilcreggan 1345 Cruise Loch Long View Cruise Ships at Greenock & Loch Goil Dunoon 1550 Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth - Sunday September 5 Kilcreggan 1615 Anthem of the Seas - Tuesday September 14 Greenock 1650 P&O’s Britannia - Friday