06Ingmee Bak£03ึมพ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

29401-Himalayan-Restaurant-Menus.Pdf

ALAYA HIM N PUN HILL KITCHEN Fine Dining Restaurant 710 N. Townsend Ave. Montrose, CO 81401 970-615-7028 Appetizers Samosa................................................................................................................$5.99 Crispy puff turnovers stuffed with potatoes, peas and spices. Bhaktapure Chhoila....................................................................................$8.99 Smokey lamb marinated with Himalayan spices. Chicken Pakora..............................................................................................$6.99 Deep-fried chicken strips battered with chickpeas flour and spices. Sabzee Pakora.................................................................................................$5.99 Deep-fried mixed vegetables battered with chickpeas flour and spices. Cheese Pakora.................................................................................................$5.99 Deep-fried cheese, battered with chickpeas flour. Aloo Achaar......................................................................................................$5.99 Boiled potato garnished with cilantro, chili, turmeric, served at room temperature. House special sampling platter..............................................................$11.99 Combination of aloo achaar, Himalayan chicken, vegetable Mo-mo and cheese pakoda. MO-MO (Typical Nepali Dumpling) Mo-mo “Dumplings” Mo-mo is one of the most popular dishes among Nepalese and Tibetans. Preparation includes wrapping stuffed meat and vegetables in flour dough, -

Fine Indian & Nepalese Cuisine

KABAB and CURRY FINE INDIAN & NEPALESE CUISINE Seekh Kabab ...............................................................15.95 APPETIZERS VEGETARIAN ENTRÉE KABAB CORNER Very lean minced lamb mixed with herbs & spices and baked on skewers. Samosa (2): Stuffed homemade triangular turnovers. Tadka Dal .......................................................... 11.95 Tandoori dishes are cooked in clay oven (Tandoor) Yellow lentils stewed and gently tempered with and served on sizzler. Vegetable (Potatoes and Peas) .................... 3.95 fresh herbs & seasoning and topped with fresh cilantro. Tandoori Fish ...............................................................17.95 Meat (Minced Lamb and Peas) .................... 5.95 Chicken Tandoori - Half ......................................... 13.95 Salmon fish marinated with paprika, turmeric, Dal Makhani ..................................................... 12.95 ginger & garlic and baked on skewers. Aloo Tikki ...................................................................... 3.95 Black lentils simmered with ginger, garlic, tomatoes, herbs & spices. Chicken tandoori is known as King of Kababs. Chicken marinated in Pan fried potatoes and pea patties deep fried. Tandoori masala & yogurt for over 24 hours and baked on skewers till Tandoori Mixed Grill .................................................19.95 Chicken Tandoori, Chicken Tikka, Boti Kebab, tender & juicy. Chana Masala ................................................... 11.95 Seekh kebab and Tandoori Shrimp. Pakoras Chickpeas cooked -

York's First Family Run Authentic

Dinner Menu NAMASTE York’s first Family run Authentic Nepalese (Gurkha Restaurant) Please inform a member of staff of any dietary or allergy requirements . 63a Goodramgate, York, YO1 7LS T: 01904 624677 • www.yakyetiyork.co.uk Email: [email protected]. Starters Aloo Dum V SS £4.99 Delicately spiced potatoes Momo with ground sesame. Momo is a type of steamed bun with a choice of filling. It has become a traditional delicacy Vegetable Pakora of Nepal, Tibet and Nepalese/ Tibetan V G £5.50 communities in Bhutan as well as all Potatoes, onions, carrots, over the Country (Recommended) ground cumin, fresh coriander and chilli to Chilli Momo taste, deep fried pakora V G S Vegetable £6.99 batter with tomato chutney. Pork £7.39 G S G S Lamb £7.39 Gurkhali Achar (New) V SS £2.50 Steamed Momo More a salad than a pickle. It’s simply Vegetable £5.90 V delicious and is best served as a starter Pork £6.10 G or side dish with rice and a meat or Lamb £6.10 G vegetable curry. Chicken Choila GF £6.99 (New) Choila is a typical dish from the Chilli Chip s V SBS £5.50 Kathmandu Valley consisting of Potato chips with stir-fry spiced grilled meat, usually eaten vegetables with fresh with beaten rice (chiura). This dish chilli to taste. is typically very spicy, mouth watering, served chilled or room temperature . Jhinge Machha G E £6.99 (Battered King Prawns) Sekuwa Pork GF £7.90 (New) Marinated with our Pork roasted on a natural wood / homemade spices & log fire in a traditional Nepalese deep fried til crispy. -

List of Asian Cuisines

List of Asian cuisines PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 26 Mar 2014 23:07:10 UTC Contents Articles Asian cuisine 1 List of Asian cuisines 7 References Article Sources and Contributors 21 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 22 Article Licenses License 25 Asian cuisine 1 Asian cuisine Asian cuisine styles can be broken down into several tiny regional styles that have rooted the peoples and cultures of those regions. The major types can be roughly defined as: East Asian with its origins in Imperial China and now encompassing modern Japan and the Korean peninsula; Southeast Asian which encompasses Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines; South Asian states that are made up of India, Burma, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan as well as several other countries in this region of the Vietnamese meal, in Asian culture food often serves as the centerpiece of social continent; Central Asian and Middle gatherings Eastern. Terminology "Asian cuisine" most often refers to East Asian cuisine (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean), Southeast Asian cuisine and South Asian cuisine. In much of Asia, the term does not include the area's native cuisines. For example, in Hong Kong and mainland China, Asian cuisine is a general umbrella term for Japanese cuisine, Korean cuisine, Filipino cuisine, Thai cuisine, Vietnamese cuisine, Malaysian and Singaporean cuisine, and Indonesian cuisine; but Chinese cuisine and Indian cuisine are excluded. The term Asian cuisine might also be used to Indonesian cuisine address the eating establishments that offer a wide array of Asian dishes without rigid cuisine boundaries; such as selling satay, gyoza or lumpia for an appetizer, som tam, rojak or gado-gado for salad, offering chicken teriyaki, nasi goreng or beef rendang as the main course, tom yam and laksa as soup, and cendol or ogura ice for dessert. -

TOWARDS a GEOGRAPHY of NEPALESE CUISINE David

62/TheThe Third Third Pole, Pole Vol. 8-10, PP 62-72:2010 TOWARDS A GEOGRAPHY OF NEPALESE CUISINE David Seddon1 Abstract This is the first part of an article which proposes to break new ground in developing a conceptual framework for and presenting a preliminary empirical analysis of ‘the geography of Nepalese cuisine’. This part of the article sets out some of the elements required for an exploration of national, regional and local cuisines. It elaborates the concept of ‘cuisine’ as a historical but constantly evolving socio-economic and cultural construct (a food tradition) within a more-or-less defined geographical area. It considers the significance of ‘food availability’ and the ways in which the ‘natural’ world is classified and categorized to define what is considered edible and what is not. It explains how food preparation and processing transforms an animal, fish or plant into a food stuff or ingredient and examines how food preparation, production (including cooking) and presentation may differ and may be associated with different styles of cuisine (high and low, complex and simple, etc.). It introduces a distinction between national, regional and local cuisines and briefly considers the treatment of ‘Indian’ cuisine. Key Words: Cuisine, Food, Food tradition, Nepal, Nepalese, Newari, Dalbhat Introduction some cases referring to the crops they grow, the livestock they produce, and the foodstuffs they It is said that ‘fools rush in where angels fear to buy and sell and consume, and in some cases to tread’. This article represents an example of just the ceremonial, religious and other ritual such a foolish initiative. -

View in 1986: "The Saccharine Sweet, Icky Drink? Yes, Well

Yashwantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University V101:B. Sc. (Hospitality and Tourism Studies) V102: B.Sc. (Hospitality Studies & Catering Ser- vices) HTS 202: Food and Beverage Service Foundation - II YASHWANTRAO CHAVAN MAHARASHTRA OPEN UNIVERSITY (43 &Øا "••≤°• 3•≤©£• & §°© )) V101: B. Sc. Hospitality and Tourism Studies (2016 Pattern) V102: B. Sc. Hospitality Studies and Catering Services (2016 Pattern) Developed by Dr Rajendra Vadnere, Director, School of Continuing Education, YCMOU UNIT 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails…………...9 UNIT 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service ………………69 UNIT 3 Food and Beverage Services in Restaurants…..140 UNIT 4 Room Service/ In Room Dinning........................210 HTS202: Food & Beverage Service Foundation -II (Theory: 4 Credits; Total Hours =60, Practical: 2 Credits, Total Hours =60) Unit – 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails: Introduction, Types (Tea, Coffee, Juices, Aerated Beverages, Shakes) Descriptions with detailed inputs, their origin, varieties, popular brands, presentation and service tools and techniques. Mocktails – Introduction, Types, Brief Descriptions, Preparation and Service Techniques Unit – 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service: Introduction, Coffee Shop, Layout, Structure, Breakfast: Concept, Types & classification, Breakfast services in Hotels, Preparation for Breakfast Services, Mise- en-place and Mise-en-scene, arrangement and setting up of tables/ trays, Functions performed while on Breakfast service, Method and procedure of taking a guest order, emerging trends in Breakfast -

Restaurant Program

RESTAURANT PROGRAM The Restaurant Voucher Program Terms and Conditions: This year, athletes will have the chance to select · The restaurant vouchers are valued at $30 each. For any purchase above this their own meal and enjoy Taupō’s local restaurants. price, the difference will need to be paid by the athlete at the time of purchase. Participating restaurants have joined Nutri-Grain · This offer is not redeemable for cash. IRONMAN New Zealand in the 2021 Athlete Restaurant · This offer must be used in one transaction. Any unused value will be forfeited. Program, opening their doors to athletes to show what the local community in Taupō has to offer. · This offer may only be used during the restaurant opening times from THURSDAY 25 - SUNDAY 28 MARCH. · You must present the voucher at the time of dining. Baked with Love We are the IRONMAN cafe. Thur - Sun: 7am - 3pm We are the newest big and beautiful cafe on the scene in Taupō. Our cabinet is 11 Gascoigne St loaded with sweet and savoury treats, some say our doughnuts are the best in 07 376 5513 the entire world... we look forward to seeing you. www.bakedwithlove.co.nz Bella Italia We are Trip Advisors “number one Italian restaurant in Taupō”. Thur - Fri: 4pm - 9:30pm Tuesday to Sunday our dinner menu ranges from handmade pizzas Sat - Sun: 11am - 9:30pm and traditional fettuccine, to beautifully prepared venison, eye fillet or fish. 13 Tongariro St During the weekend we also open for lunch you can relax and enjoy lake views. 07 377 4003 We also do takeaways. -

Culinary Quiz: 20 Questions with Answers

kupidonia.com Culinary Quiz: 20 questions with answers. What do they cook in different countries? Culinary Quiz: 20 questions with answers. What do they cook in different countries? - 1 / 7 kupidonia.com 1. Sepik is an Estonian traditional dish. What is it? fish soup wholemeal bread curd dessert. 2. There are a lot of curious legends around the dishes of the national cuisine, which do not always correspond to reality. Which Italian pie, according to legend, has been known since ancient times, when it was prepared on the occasion of the pagan spring f pizza flammkuchen pastiera 3. This dish is traditional for Indian and Nepalese cuisine. There are many variations of its preparation, but most often it is based on cooked rice and a thick lentil soup puree. In Nepal, this dish is called dal-bhat. What is it called in India? thali ghee chutney 4. What is a traditional dish of beans, meat products, and cassava flour (farofa) called in Portuguese-speaking countries? feijoada fondue farofa Culinary Quiz: 20 questions with answers. What do they cook in different countries? - 2 / 7 kupidonia.com 5. What is the name of the North African dish of meat and vegetables and special ceramic utensils for its preparation? tagine putels bagrir 6. This traditional Iranian dessert comes from Shiraz. It has been known since the 5th century BC and is one of the first known types of ice cream. What is it called? pandan falude sago 7. What is the national Scottish dish of lamb giblets, with onions, toloko, lard, seasonings, and salt, boiled in a lamb's stomach? chorbu haggis. -

Tilak Maharashtravidyapeeth, Pune Cb M.Sc

TILAK MAHARASHTRAVIDYAPEETH, PUNE CB M.SC. IN NUTRITION & FOOD SCIENCE EXAMINATION : APRIL - 2019 FOURTH SEMESTER Sub. : Ayurvedic Diet Planning (M.Sc. CB-412) Date: 25/04/2019 Total marks: 60 Time: 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Instructions: 1) All questions are compulsory. 2) Figures to the right indicate full marks. SECTION A Q. 1 Select the correct alternative. (05) 1) -------------type of food is good in obesity a) laghu b) apatrpan c) guru d) b and c 2) Ginger and saindhav a) increases appetite b) decreases appetite c) none of above d) both a and b 3) The rasa of madhu is --- a) madhur and kashay b) tikta c) lavan d) amla 4) The causative factor for the kushtha is a) atyashan b) virudhashan c) adhyashan d) samashan 5) In sthaulya or obesity,there is -------in appetite a) increase b) decrease c) no any change d)can not be judged Q. 2 Answer the following questions. (Any One) (15) 1) Write detail diet plan for prameha considering ayurvedic approach. 2) Discuss importance of types of Yavagu in agnimandya in different diseases. Q. 3 Write a Short note. (Any two) (10) 1) shadangpaniya 2)Diet in Pandu 3)Takra SECTION B Q. 1 Select the correct alternative. (05) 1) Use of kokum in food preparation is distinctive feature of a) Goa b) Madhya Pradesh c) Uttar Pradesh d) assam 2) …… is a multicourse meal in Kashmiri tradition a) Ghewar b) Wazwan c)Junglee maas d) Dal bati 3) …… is not related to Mexican food. a) Mole b)Agave c) Masa d) none of these 4) Nepalese cuisine is common in …. -

Download Travel Guide

A TREKKERS' PARADISE Travel Guide for Nepal KNOW BEFORE YOU GO Greeting & Culture Religion & language Festivals Cuisine Best time Experience Souvenirs Itinerary visa Flight Travel Tips GREETING & CULTURE GREETING CULTURE The Nepali greeting, Namaste (“I salute the god Many different ethnic groups coexist in Nepal, each within you”), where your palms are held together with their own complex customs. Nepal's rich and as if you are praying, is one of the best of diverse culture is reflected in the proud showcase of Nepalese customs. Along with the Namaste comes its music, dance and language. The three ethnic a warm greeting to guests who are regarded as groups Indigenous Nepalese, Indo-Nepalese and gods and are treated with great respect. If you want Tibeto-Nepalese are based on the diverse to show great respect, namaskar is a more formal or geography of the country. Culture in Nepal is a subservient variant. symbol of the nation's wealthy, harmonized and diversified society RELIGION & LANGUAGE Nepal, often described as the Switzerland of Asia, is a small but diverse nation. The Himalayan Mountains are the highlight and full of awe- inspiring scenery. Besides the Himalayan mountains the so called “Heaven on Earth” offers other fascinating landscapes like the birthplace of Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. RELIGION LANGUAGE As a secular country, Nepal welcomes new religions The national language of Nepal is Nepalese or as it enhances the diversity of culture. Hinduism as the locals say Nepali. Nepali is spoken and Buddhism are the main religions in throughout Nepal with only a few parts of Nepal left, Nepal and they have co-existed in harmony through where it is not spoken. -

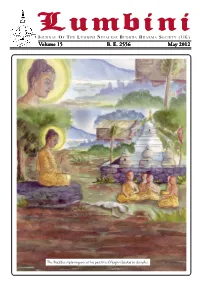

Lumbini Journal 12.Pmd

LumbiniLumbiniLumbini J OURNAL O F T HE L UMBINI N EPALESE B UDDHA D HARMA S OCIETY (UK) Volume 15 B. E. 2556 May 2012 The Buddha explaning one of his past lives (Vyaghri Jataka) to disciples. Lumbini Nepalese Buddha Dharma Society (UK) uddha was born more than 2600 years ago at Lumbini in Nepal. His teachings of existence of suffering and Lumbini the way out of the suffering are applicable today as they were B Journal of The Lumbini Nepalese Buddha Dharma Society (UK) applicable then. The middle way he preached is more appropriate now than ever before. Lumbini is the journal of LNBDS (UK) and published annually For centuries Buddhism remained the religion of the East. depending upon funds and written material; and distributed free Recently, more and more Westerners are learning about it of charge as Dharma Dana. It is our hope that the journal will and practising Dharma for the spiritual and physical well- serve as a medium for: being and happiness. As a result of this interest many monasteries and Buddhist organisations have been 1.Communication between the society, the members and other established in the West, including in the UK. Most have Asian interested groups. connections but others are unique to the West e.g. Friends of Western Buddhist Order. 2.Publication of news and activities about Buddhism in the United Kingdom, Nepal and other countries. Nepalese, residing in the UK, wishing to practice the Dharma for their spiritual development, turned to them as there were no such Nepalese 3.Explaining various aspects of Dharma in simple and easily organisations. -

In Terms of Food, Vietnamese Cuisine and Nepalese Cuisine Have Similarities As Well As Differences

In terms of food, Vietnamese cuisine and Nepalese cuisine have similarities as well as differences. Vietnamese cooking is greatly admired for its fresh ingredients, minimal use of dairy and oil, complementary textures, and reliance on herbs and vegetables. With the balance between fresh herbs, meats and selective use of spices to reach a fine taste, Vietnamese food is considered as one of the healthiest cuisine worldwide. In terms of Nepalese cuisine, much of the cuisine is a variation on Asian themes. Other foods have hybrid Tibetan, Indian and Thai origins. Momo - Tibetan style dumplings with Nepalese spices - are one of the most popular foods in Nepal. Rice is grown in the Terai region and hence consumed by the whole country making ‟DaalBhaat” the national food of the country. Both Vietnam and Nepal consume rice as part of their daily meals. This project is intended to bring Vietnamese and Nepalese dishes together. This project wants to fill the gap between two nations and hence wants to bring two countries together by exposing participants to food culture and culinary educational opportunities from different cultural, religious, geographical and socio-economic backgrounds so that it will provide the experience for participants to develop a greater understanding of diversity. Exchange participants /students will contribute their experience on practical matters during and after the exchange, as “Food Ambassadors” to bring inter cultural learning and practices of diverse cuisines to both institutions, ultimately being the promoters of a new fusion cuisine. Following their return to either Nepal or Vietnam, participants then need to complete their individual reports on the program.