View Checklist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hausenstein's Klee in the Year 1921, in His Book Kairuan, Oder Eine

Charles W. Haxthausen Paul Klee, Wilhelm Hausenstein, and «the Problem of Style» Guten Tag, Monsieur Ich, was haben Sie heute für eine Krawatte umgebunden? möchte man manchmal einem «Kunstwerk» zu- rufen. Paul Klee, Tagebücher, 1906 Hausenstein’s Klee In the year 1921, in his book Kairuan, oder eine Geschichte vom Maler Klee und von der Kunst dieses Zeitalters, the eminent German art critic Wilhelm Hausenstein de- clared his subject the quintessential artist of his era. Yet his reasons made the honor an ambiguous one: Wir […] sind in die Epoche des Anarchischen und der Disgregation eingetreten. […] Der Malerzeichner Klee nahm von der Zeit, was sie war. Er sah, was sie nicht war; sah ihr Va- kuum, ihre Sprünge; sah ihre Ruinen und saß über ihnen. Sein Name bedeutet kein Sys- tem. Seine Kunst ist irrational, selbst in der raffiniertesten Überlegung naiv, ist der uner- hörten Verwirrung des Zeitalters hingegeben.1 Such gloomy words seem strangely discordant with our image of Klee. They must have seemed especially incongruous when read alongside the artworks illustrat- ing Hausenstein’s book. For most of us familiar with Klee’s art, his name evokes humor and charm, fantasy and poetry, witty and evocative titles, aesthetic en- chantment, delights for the mind as well as the eye—not «Sprünge» and «Ruinen», not anarchy and disintegration. What «Verwirrung» was Hausenstein talking about? To be sure, the confusion of modernity was by then a well-estab- lished trope, yet if we read Hausenstein’s previous writing we will see that he had something more specific in mind. The symptom of the confusion of the age was the confusion of styles, and that confusion was manifest in Klee’s art more than in any other. -

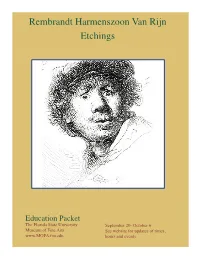

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING in SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00

A Q U A T I N T : P R I N T I N G I N S H A D E S GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY 74 Heath Street Hampstead Village London NW3 1DN AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING IN SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00 GILDENSARTS.COM [email protected] +44 (0)20 7435 3340 G I L D E N ’ S A R T S G A L L E R Y GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES April – June 2015 Director: Ofer Gildor Text and Concept: Daniela Boi and Veronica Czeisler Gallery Assistant: Costanza Sciascia Design: Steve Hayes AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES In its ongoing goal to research and promote works on paper and the art of printmaking, Gilden’s Arts Gallery is glad to present its new exhibition Aquatint: Printing in Shades. Aquatint was first invented in 1650 by the printmaker Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) in Amsterdam. The technique was soon forgotten until the 18th century, when a French artist, Jean Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), rediscovers a way of achieving tone on a copper plate without the hard labour involved in mezzotint. It was however not in France but in England where this technique spread and flourished. Paul Sandby (1731 - 1809) refined the technique and coined the term Aquatint to describe the medium’s capacity to create the effects of ink and colour washes. He and other British artists used Aquatint to capture the pictorial quality and tonal complexities of watercolour and painting. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

Materials for Printmaking

A COMPARATIVE STUDY. OF CONVENTIONAL AND EXPANDABLE ACIn RESISTANT STOPOUT MATERIALS FOR PRINTMAKING A Creative Project Presented to The School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfillment ot the Requirements tor the Degree Master ot Fine Arts by Lyle F. Boone January 1970 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CONVENTIONAL AND EXPANDABLE ACID RESISTANT STOPOUT MATERIALS FOR PRINTMAKING Lyle F. Boone Approved by Committee: TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • 1 The problem • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Definitions of terms used • • • • • • • • 2 Lift-ground • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Ground • • • • • • • • • • 2 Rosin • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Stopout • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 Procedure • • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 II. THE CONVENTIONAL METHOD OF STOPPING OUT • • • 7 Conventiona.1 Uses of Shella.c Stopout with Ha.rd and Soft-ground • • • 8 Conventional Use of' Shellac Stop,·ut with Aqua.tint • • • • • • • • • 13 Conventional Materials for Li.ft-ground • • 18 III. NON-CONVENTIONAL METHODS OF USING EXPANDABLE ACID RESISTANT STOPOUT MATERIALS • • • 22 Non-conventional Stopout with Ha.rd and So.ft ground • • • • • • • • • • • 24 Non-conventional Materials for Aquatint • • • 26 Non-conventional Materia.ls with Lift-ground • • 29 IV. CREATIVE APPLICATION OF FINDINGS • • 38 v. CONCLUSION • • • • • • 52 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • 54 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE PAGE 1. Print Containing Hard and Soft-ground Etching, Aquatint, Copper, Size 8" x 11-1/2". • • • 12 2. Area Indicating Shellac Breakdown, Containing Hard and Soft-ground Etching, Aquatint, Zino, Size 8" x 6" • • • . • • • • • 14 3. Aqua.tint, Hard and Soft-~round Etching on " ff - Copper, Size 8 x 12 •••••• • • 15 4. Print Containing Lift-ground, Aquatint, Hard ft ft ground Etohing, Copper, Size 4 x 6 • • • 20 Print Containing Aquatint, Copper, Size 4 tt x 5" 7. -

The Exploration of Light As a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 8-7-1972 The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vasko, Mary, "The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPLORATION OF LIGHT AS A MEANS OF EXPRESSION IN THE INTAGLIO PRINT MED I UH by Sister Mary Lucia Vasko, O.S.U. Candidate for the Master of Fine Arts in the College of Fine and Applied Arts of the Rochester Institute of Technology Submitted: August 7, 1372 Chief Advisor: Mr. Lawrence Williams TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . i i i INTRODUCTION v Thesis Proposal V Introduction to Research vi PART I THESIS RESEARCH Chapter 1. HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS AND BACKGROUND OF LIGHT AS AN ARTISTIC ELEMENT THE USE OF CHIAROSCURO BY EARLY ITALIAN AND GERMAN PRINTMAKERS INFLUENCE OF CARAVAGGIO ON DRAMATIC LIGHTING TECHNIQUE 12 REMBRANDT: MASTER OF LIGHT AND SHADOW 15 Light and Shadow in Landscape , 17 Psychological Illumination of Portraiture . , The Inner Light of Spirituality in Rembrandt's Works , 20 Light: Expressed Through Intaglio . Ik GOYA 27 DAUMIER . 35 0R0ZC0 33 PICASSO kl SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION OF RESEARCH hi PART I I THESIS PROJECT Chapter Page 1. -

A Student Guide to the Use of Soft Grounds in Intaglio Printmaking

A STUDENT GUIDE TO THE USE OF SOFT GROUNDS IN INTAGLIO PRINTMAKING Submitted by Lori Jean Ash Department of Art Concentration Paper In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS page List of Illustrations ••••••••••••••••• ii A Student Guide to the Use of Soft Ground in Intaglio Printmaking I. Introduction •••••••••••••••• ........................ 1 II. Materials and Methodology •••••••••••••••• 7 III. Conclusions•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 22 Endnotes. • . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • • . • . 23 BibliographY••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 25 ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS page Figure 1: Rembrandt van Rijn, Self Portrait by Candlelight •••••• 3 Figure 2: Jaques Callot, The Lute Player •••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Figure 3: s.w. Hayter, Amazon ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 Figure 4: Mauricio Lasansky, Dachau ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 19 Figure 5: Mauricio Lasansky, Amana •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Figure 6: Mauricio Lasansky, Study-Old Lady and Bird •••••••••••• 21 I. INTRODUCTION With the possible exception of drypoint and engraving, all intaglio processes involve the use of some type of ground. Though this acid resistant material has many applications, it has but one primary function, which is to protect the plate surface from the action of the acid during the etch. The traditional hard etching ground is made from asphaltum thinned with gum turpentine and forms a hard, stable surface suitable for work with a etching needle or other sharp tool. Soft ground has had some agent added to it which prevents it from ever becoming completely hard. It adheres to whatever touches it and can be easily removed from the plate by pressing some material into the ground and then lifting it, exposing the plate in those areas where pressure was applied. -

Morton Review

REVIEWS: Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture 549 Morton, Marsha. Max Klinger and Wilhelmine Culture. On the Threshold of German Modernism. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. 434 pp. £80.00 (hardcover). Max Klinger’s (1857–1920) life-size, polychrome marble sculpture of Ludwig van Beet- hoven formed the centerpiece of the 14th Vienna Secession Exhibition in 1902. In many ways, the exhibition wasasmuch a celebration ofthe Leipzig artist asit wasofthe great composer. By this point in time, Klinger had reached the zenith of his international fame as a modern artist and yet, his art historical position soon started to become increasingly precarious—especially after his death in 1920. Although his drawings and print cycles continued to enter private and public collections (especially in the United States), Klinger’s idiosyncratic realism—especially in his paintings—posed an insurmountable challenge to post-war formalism and abstraction. Klingerwasvirtuallyforgottenuntilthe1960sand1970s,whenaseriesofexhibitionsandpub- lications gradually generated renewed interest. Since then, Klinger slowly made his way back into the “story of modern art” but most of the scholarship continues to be offered in German. Marsha Morton’s 2014 publication under review here changes this unsatisfactory situation and makes a significant intervention not only in Klinger scholarship but also in the study of late nineteenth-century German art and culture more generally. Morton’s book is so multi-faceted that this short review cannot do it justice. But her key thesis is constructed around Klinger’s evocative visual engagement with the disquieting psy- chological undercurrents of modern urban life. This analytical emphasis on the psychological rather than an exclusively formalist modernism is part of a broader shift in the literature (the work of Debora L. -

The Silverman Collection

Richard Nagy Ltd. Richard Nagy Ltd. The Silverman Collection Preface by Richard Nagy Interview by Roger Bevan Essays by Robert Brown and Christian Witt-Dörring with Yves Macaux Richard Nagy Ltd Old Bond Street London Preface From our first meeting in New York it was clear; Benedict Silverman and I had a rapport. We preferred the same artists and we shared a lust for art and life in a remar kable meeting of minds. We were more in sync than we both knew at the time. I met Benedict in , at his then apartment on East th Street, the year most markets were stagnant if not contracting – stock, real estate and art, all were moribund – and just after he and his wife Jayne had bought the former William Randolph Hearst apartment on Riverside Drive. Benedict was negotiating for the air rights and selling art to fund the cash shortfall. A mutual friend introduced us to each other, hoping I would assist in the sale of a couple of Benedict’s Egon Schiele watercolours. The first, a quirky and difficult subject of , was sold promptly and very successfully – I think even to Benedict’s surprise. A second followed, a watercolour of a reclining woman naked – barring her green slippers – with splayed Richard Nagy Ltd. Richardlegs. It was also placed Nagy with alacrity in a celebrated Ltd. Hollywood collection. While both works were of high quality, I understood why Benedict could part with them. They were not the work of an artist that shouted: ‘This is me – this is what I can do.’ And I understood in the brief time we had spent together that Benedict wanted only art that had that special quality. -

Printmaking Through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012

Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Printmaking as Art 6 Glossary of Printing Terms 7 A Brief History of Printmaking Written by Jennifer Jensen 10 Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap , Rembrandt Written by Hailey Leek 11 Lesson Plan for Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap Written by Virginia Catherall 14 Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo, Hokusai Written by Jennifer Jensen 16 Lesson Plan for Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo Written by Jennifer Jensen 20 Lambing , Leighton Written by Kathryn Dennett 21 Lesson Plan for Lambing Written by Kathryn Dennett 32 Madame Louison, Rouault Written by Tiya Karaus 35 Lesson Plan for Madame Louison Written by Tiya Karaus 41 Prodigal Son , Benton Written by Joanna Walden 42 Lesson Plan for Prodigal Son Written by Joanna Walden 47 Flotsam, Gottlieb Written by Joanna Walden 48 Lesson Plan for Flotsam Written by Joanna Walden 55 Fourth of July Still Life, Flack Written by Susan Price 57 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 59 Reverberations, Katz Written by Jennie LaFortune 60 Lesson Plan for Reverberations Written by Jennie LaFortune Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership and the Professional Outreach Programs in the Schools (POPS) through the Utah State Office of Education 1 Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Image List 1. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume , 1638 Etching Gift of Merrilee and Howard Douglas Clark 1996.47.1 2. -

Surreal Visual Humor and Poster

Fine Arts Status : Review ISSN: 1308 7290 (NWSAFA) Received: January 2016 ID: 2016.11.2.D0176 Accepted: April 2016 Doğan Arslan Istanbul Medeniyet University, [email protected], İstanbul-Turkey http://dx.doi.org/10.12739/NWSA.2016.11.2.D0176 HUMOR AND CRITICISM IN EUROPEAN ART ABSTRACT This article focused on the works of Bosh, Brughel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön and Kubin, lived during and after the Renaissance, whose works contain humor and criticism. Although these artists lived in from different cultures and societies, their common tendencies were humor and criticism in their works. Due to the conditions of the period where these artists lived in, their artistic technic and style were different from each other, which effected humor and criticism in the works too. Analyzes and comments in this article are expected to provide information regarding the humor and criticism of today’s Europe. This research will indicate solid information regarding humor and tradition of criticism in Europe through comparisons and comments on the works of the artists. It is believed that, this research is considered to be useful for academicians, students, artists and readers who interested in humour and criticism in Europe. Keywords: Humour, Criticism, Bosch, Gillray, Grandville AVRUPA SANATINDA MİZAH VE ELEŞTİRİ ÖZ Bu makale, Avrupa Rönesans sanatı dönemi ve sonrasında yaşamış Bosch, Brueghel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön ve Kubin gibi önemli sanatçıların çalışmalarında görülen mizah ve eleştiri üzerine kurgulanmıştır. Bahsedilen sanatçılar farklı toplum ve kültürde yaşamış olmasına rağmen, çalışmalarında ortak eğilim mizah ve eleştiriydi. Sanatçıların bulundukları dönemin şartları gereği çalışmalarındaki farklı teknik ve stiller, doğal olarak mizah ve eleştiriyi de etkilemiştir.