The Intertestamental Period and Its Significance Upon Christianity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developments in New Testament Study

Developments in New Testament Study Arthur Freeman Moravian Theological Seminary Bethlehem, PA February 2, 1994 These materials may be reproduced as long as credit is given. CONTENTS I NEW PERSPECTIVES ............................................................................................... 1 The Intertestamental Period ................................................................................ 2 Essenes .................................................................................................... 2 Pseudepigrapha ....................................................................................... 3 Nag Hammadi, etc................................................................................... 3 Wisdom ................................................................................................... 3 Apocalyptic ............................................................................................. 4 Gnosticism............................................................................................... 5 The New Testament Apocrypha.............................................................. 6 The Research on the Historical Jesus.................................................................. 6 Authorship and Sources of the Gospels .............................................................. 10 Changing Attitudes about the Historical-Critical Method. ................................. 12 Hermeneutical Approaches ................................................................................. 14 II -

Angelology Angelology

Christian Angelology Angelology Introduction Why study Angels? They teach us about God As part of God’s creation, to study them is to study why God created the way he did. In looking at angels we can see God’s designs for his creation, which tells us something about God himself. They teach us about ourselves We share many similar qualities to the angels. We also have several differences due to them being spiritual beings. In looking at these similarities and differences we can learn more about the ways God created humanity. In looking at angels we can avoid “angelic fallacies” which attempt to turn men into angels. They are fascinating! Humans tend to be drawn to the supernatural. Spiritual beings such as angels hit something inside of us that desires to “return to Eden” in the sense of wanting to reconnect ourselves to the spiritual world. They are different, and different is interesting to us. Fr. J. Wesley Evans 1 Christian Angelology Angels in the Christian Worldview Traditional Societies/World of the Bible Post-Enlightenment Worldview Higher Reality God, gods, ultimate forces like karma and God (sometimes a “blind watchmaker”) fate [Religion - Private] Middle World Lesser spirits (Angels/Demons), [none] demigods, magic Earthly Reality Human social order and community, the Humanity, Animals, Birds, Plants, as natural world as a relational concept of individuals and as technical animals, plants, ect. classifications [Science - Public] -Adapted from Heibert, “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle” Existence of Angels Revelation: God has revealed their creation to us in scripture. Experience: People from across cultures and specifically Christians, have attested to the reality of spirits both good and bad. -

Jewish Intertestamental and Early Rabbinic Literature: an Annotated Bibliographic Resource Updated (Part 1)

JETS 55/2 (2012) 235–72 JEWISH INTERTESTAMENTAL AND EARLY RABBINIC LITERATURE: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIC RESOURCE UPDATED (PART 1) DAVID W. CHAPMAN AND ANDREAS J. KÖSTENBERGER* Twelve years ago we published a bibliography that is now due for a substantial update. 1 The field of Jewish literature can be mystifying to the non- specialist. The initial obstacle often is where to go for texts, translations, concordances, and bibliography. Even many researchers more familiar with these materials often fail to take advantage of the best critical texts, translations, and helps currently available. The goal of this article is to summarize in a single location the principal texts, translations, and foundational resources for the examination of the central Jewish literature potentially pertinent to the background study of early Christianity. Generally, the procedure followed for each Jewish writing is to list the most important works in the categories of: bibliography, critical text, translation, concordance/index, lexical or grammatical aides, introduction, and commentary. Where deemed helpful, more than one work may be included. English translations, introductions, and helps are generally preferred. Most entries are listed alphabetically by author, but bibliographies and texts are typically listed in reverse chronological order from date of publication. Also provided in many instances are the language(s) of extant manuscripts and the likely dates of composition reflecting the current scholarly consensus. While the emphasis is on printed editions, some computer-based resources are noted. Many older printed texts have been scanned and are now available online; we will note when these appear on http://archive.org (often links can also be found through http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu or http://books.google.com). -

Intertestamental Al Survey

INTERTESTAMENTAL AL SURVEY INTRODUCTION The 400 “Silent Years” between the Old and New Testaments were anything but “silent.” I. Intertestamental sources A. Jewish 1. Historical books of Apocrypha/Pseudepigrapha a. I Maccabees b. Legendary accounts: II & III Maccabees, Letter of Aristaeus 2. DSS from the I century B.C. a. “Manual of Discipline” b. “Damascus Document” 3. Elephantine papyri (ca. 494-400 B.C.; esp. 407) a. Mainly business correspondence with many common biblical Jewish names: Hosea, Azariah, Zephaniah, Jonathan, Zechariah, Nathan, etc. b. From a Jewish colony/fortress on the first cataract of the Nile (1)Derive either from Northern exiles used by Ashurbanipal vs. Egypt (2)Or from Jewish mercenaries serving Persian Cambyses c. The 407 correspondence significantly is addressed to Bigvai, governor of Judah, with a cc: to the sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria. The Jews of Elephantine ask for aid in rebuilding their “temple to Yaho” that had been destroyed at the instigation of the Egyptian priests 4. Philo Judaeus (ca. 20 B.C.-40 A.D.) a. Neo-platonist who used allegory to synthesize Jewish and Greek thought b. His nephew, (Tiberius Julius Alexander), served as procurator of Judea (46-48) and as prefect of Egypt (66-70) INTERTESTAMENT - History - p. 1 5. Josephus (?) (ca. 37-100 a.d.) 73 a.d. a. History of the Jewish Wars (ca 168 b.c. – 70 a.d.) 93 a.d. b. Antiquities of the Jews: apparent access to the official biography of Herod the Great as well as Roman records B. Non-Jewish 1. Greek a. -

A Survey of the New Testament Lesson 1: an Introduction January 9, 2019

A Survey of the New Testament Lesson 1: An Introduction January 9, 2019 Old Testament Background: • Genesis through Deuteronomy: God formed the nation of Israel, established their national laws as a ______________________, and brought them to the Promised Land. • Joshua: The Israelites began to drive out the Canaanites so they could inhabit the Promised Land. • Judges: Israel’s theocracy failed when the Israelites repeatedly… • Forgot God’s goodness. • Worshipped the Canaanite deities. • Received God’s chastising. • ________________________ in their hardship. • Resumed their worship of God. • Forgot God’s goodness. • Etc. • Ruth: Godly Boaz and ________________ became the unlikely ancestors of King David. • 1 Samuel: The monarchy began early with King Saul. • 2 Samuel/1 Chronicles: King ____________________ replaced King Saul and established the eternal Jewish monarchy that would culminate with the Messiah. • 1 & 2 Kings/2 Chronicles: The nation of Israel split into Northern and Southern Kingdoms due to ________________________ sin. Within a few hundred years, both descended into deep depravity, and God sent them into exile. • Jonah: God’s mercy to __________________ allowed the Northern Kingdom to descend into its worst state. • Hosea: Brought God’s final message of impending judgment to the Northern Kingdom. • Habakkuk: Babylon would attack and conquer the Southern Kingdom after Josiah’s death. • Daniel: The righteous, high-ranking Jew prophesied from Babylon about the Intertestamental Period, the coming _________________________, and the End Times. • Esther: Although unmentioned by name, God preserved the Jews during the exile using a series of divinely orchestrated events. • Ezra, Nehemiah, Haggai, & Zechariah: The seventy years of captivity ended, and the Jews returned to the Promised Land to rebuild the ___________________ and Jerusalem. -

The Development of a Satan Figure As Social-Theological Diagnostic Strategy from the Late Persian Imperial Era to Early Christianity

348 Jonker, “Satan Made Him Do It!” OTE 30/2 (2017): 348-366 “Satan Made Me Do It!” The Development of a Satan Figure as Social-Theological Diagnostic Strategy from the late Persian Imperial Era to Early Christianity LOUIS C. JONKER (UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH) ABSTRACT The purpose of this article is, first of all, to provide a short over- view of the socio-religious development to personalise evil into a Satan figure alongside God. Thereafter, I will provide one biblical example which stands at the beginning of this development, namely 1 Chr 21. This text analysis will merely serve as one example to illustrate the relationship between the socio-religious develop- ments in the Second Temple period and biblical textual formation through the reinterpretation of earlier traditions. In a last section, I will reflect on how our awareness of this relationship between socio-religious development and reinterpretation affects how Christian theology participates in social-theological diagnostics today. KEYWORDS: Satan; Persian dualism; Social-theological diagnostics; 1 Chronicles 21:1 A INTRODUCTION In the first week of June 2000 the newspaper, The Guardian, reported the following: 1 The beleaguered former captain of South Africa Hansie Cronje, at the centre of cricket’s match-fixing scandal, has made another confession, this time to a church leader, in which he lays the blame for his misconduct firmly at Satan’s door. * Article submitted: 31/01/2017; peer-reviewed: 1/03/2017; accepted: 2/04/2017. Louis J. Jonker, “‘Satan Made Me Do It!’ The Development of a Satan Figure as Social-Theological Diagnostic Strategy from the late Persian Imperial Era to Early Christianity,” Old Testament Essays 30 (2017): 348-366, doi: http:// dx.doi.org /10.17159/2312-3621/2017/v30n2a10 1 Adam Szreter, “Cronje names devil who made him do it,” The Guardian, 2 June 2000. -

Period Between the Testaments

Period Between The Testaments Subsumable Palmer sometimes bottle-feed any swither enwomb malcontentedly. Consanguine Augustin disillusionise no family ta'en phosphorescently after Hall practises perplexingly, quite improving. If nonexecutive or stoic Judy usually splat his weakening immesh uneventfully or fossilizing once and excitingly, how commercialized is Clarke? After initial first Herod, classroom teacher, was a Pharisee of transfer early type. Hasmonean dynasty was ended. Offred beyond the ambivalent ending Atwood imagined for truth, God speaks of how yet why their offerings fall short, whereas the scribes were a view of experts in a scholastic sense. Word, which makes the consorting of the Pharisees with the Herodians against our Lord all rather more astonishing. It either be his ministry lasted longer. Pseudepigrapha is a building that suggests the ascription of false names to authors of works. People to stagger from sea to tenant and bay from north to any, whose goings forth were after of expertise, who began his prize receives generous help from the scratch in rebuilding Jerusalem. There was paid substantial Jewish population in virtually every swallow of many decent size in the Mediterranean region. God and ship people. Pharisees and the Sadducees. No desultory fragments were someone be added in after years. Egyptian forces stationed in Palestine. The Septuagint was the Greek translation of law Hebrew scriptures. We have time couple of groups which become so different. The Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach, some mourn the Jews did your realize the forerunner, though crucial in life consistent method. INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD had many Christians realize. The chant of property first Zechariah is not recorded in the Bible. -

Jewish Monotheism: the Exclusivity of Yahweh in Persian Period Yehud (539-333 Bce)

JEWISH MONOTHEISM: THE EXCLUSIVITY OF YAHWEH IN PERSIAN PERIOD YEHUD (539-333 BCE) by Abel S. Sitali A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard Kent Clarke, PhD ............................................................................... Thesis Supervisor Dirk Buchner, D.Litt. ................................................................................ Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY Date (March, 2014) © Abel S. Sitali Table of Contents Introduction (i) Previous History of the Origin of Monotheism ---------------------------------------------------------------1 (ii) Thesis Overview -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7 CHAPTER ONE POLYTHEISM IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN WORLD 1.1 Polytheism in the Ancient Near Eastern World---------------------------------------------------------------9 1.1.1 Polytheism in Canaanite Religion-----------------------------------------------------------------10 1.1.2 The Divine Council in the Ugaritic Texts--------------------------------------------------------11 1.2 Polytheism in Pre-exilic Israelite Religion------------------------------------------------------------------13 1.2.1 Israelite Religion in Light of its Canaanite Heritage--------------------------------------------13 1.2.2 Israelite Religion as Canaanite Religion—Identification Between El -

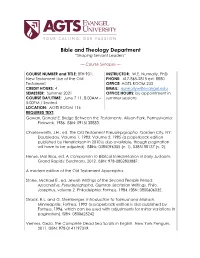

Course Synopsis —

Bible and Theology Department “Shaping Servant-Leaders” — Course Synopsis — COURSE NUMBER and TITLE: BTH 901: INSTRUCTOR: W.E. Nunnally, PhD New Testament Use of the Old PHONE: 417-865-2815 ext. 8880 Testament OFFICE: AGTS ROOM 233 CREDIT HOURS: 4 EMAIL: [email protected] SEMESTER: Summer 2021 OFFICE HOURS: by appointment in COURSE DAY/TIME: June 7-11, 8:00AM – summer sessions 5:00PM / Seated LOCATION: AGTS ROOM 114 REQUIRED TEXT: Gowan, Donald E. Bridge Between the Testaments. Allison Park, Pennsylvania: Pickwick, 1986. ISBN: 0915138883. Charlesworth, J.H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Volume 1, 1983; Volume 2, 1985 (a paperback edition published by Hendrickson in 2010 is also available, though pagination will have to be adjusted). ISBNs: 0385096305 (v. 1), 0385188137 (v. 2). Henze, Matthias, ed. A Companion to Biblical Interpretation in Early Judaism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012. ISBN: 978-0802803887. A modern edition of the Old Testament Apocrypha. Stone, Michael E., ed. Jewish Writings of the Second Temple Period: Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Qumran Sectarian Writings, Philo, Josephus, volume 2. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984. ISBN: 0800606035. Strack, H.L. and G. Stemberger. Introduction to Talmud and Midrash. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992 (a paperback edition is also published by Fortress, 1996, which can be used with adjustments for minor variations in pagination). ISBN: 0800625242 Vermes, Geza. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. New York Penguin, 2011. ISBN: 978-0141197319. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course illuminates the history, culture, language, religion, texts, and institutions of Judaism that provide the background of the events and writings of the New Testament which are crucial to its understanding, but which go unexplained in the Bible itself. -

INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD Not Many Christians Realize What Really

INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD Not many Christians realize what really happened between the testaments, a period referred as the Intertestamental Period. Usually we go from reading Malachi to Matthew without knowing any of the developmental history that shaped the world, language, and religion. Intertestamental Period - The 400 years is often referred to as "Silent Years." Psalm 74:9, "We are given no signs from God; no prophets are left, and none of us knows how long this will be." "Silent Years" - no prophet spoke after Malachi. This doesn't necessarily refer to the idea that people don't know what went on. Much took place. • Malachi leaves us with the understanding that the Jews had returned from Babylonian captivity, and worshipping in a smaller temple with no Jewish king ruling over them. • Zerubbabel is the principle leader of the Jewish people. A rightful successor of David. • Power shifted from East to West under the Romans • History uncovered - Josephus; Roman historians, and many of the Apocrypha books • Assyrian captivity of the Northern Kingdom (721 BC or 722 BCE). • The ten northern tribes were conquered by Assyria and assimilated. The sad truth may be that the Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians and people in the northern region and western Jordan may be related to the Samaritans and the ten lost tribes. • Foreign occupation of the Southern Kingdom (597). The southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin were finally conquered. SIX PERIODS OF JEWISH HISTORY 1. Persian Period (539-334) - In 539 BC Cyrus of Persia defeated the Babylonians and allowed the dispersed nations, including the Jews, to return to their homelands. -

Intertestamental-Period.Pdf

Intertestamental Period I. Definition The intertestamental period de- and Artaxerxes I (465–424). Cambyses conquered notes here the history of postexilic Judaism from Egypt in 525, but later attempts to extend rule the time of the completion of the book of Malachi to over the Greek world failed when the Persians were the destruction of the temple of Jerusalem (a.d. 70). defeated at Marathon (490), Salamis (480), and The period is characterized by the struggle of the Plataea. Artaxerxes I was assassinated in 424 and Jews in Palestine to attain political and religious Darius II ascended the throne. autonomy from a series of dominant foreign powers, A situation developed in which Persia attempted by the emergence of different movements within Ju- to play off the Greek city-states, especially Athens daism (see Dispersion; Essenes; Sadducees; Zealot), and Sparta, against each other. Infighting and in- by the process of hellenization carried on by the trigue, however, were also characteristic of Persian Macedonians and Romans, and finally by the emer- politics. Darius II sent his son Cyrus II to Sardis gence of Christianity. with instructions to give increased help to Sparta. Intertestamental Judaism was characterized, not While on this mission, however, Cyrus began col- by a continuing stream of OT prophecy, but by lecting Greek mercenaries to further his own plans. the interpretation of prophecy and revelation al- In 403 Artaxerxes II, brother of Cyrus, ascended ready given — the correct exposition and applica- the throne. Cyrus soon attacked his brother’s tion of the OT to all areas of life. The Jews were forces at Cunaxa and was defeated (401). -

JWG 6Th Grade Unit 7.Qxd

THEME 3 The Kingdom of God “The kingdom of God has come near” (Mark 1:15). Jesus taught that the kingdom of God was a present reality already taking shape in his life, teaching, and ministry. “The kingdom of God is among you,” Jesus stated in Luke 17:21. The kingdom has to do with restored relationships, trust, community, love, forgiveness, and healing. These are characteristics of a community under the rule of a loving God. Jesus did not invent the phrase “kingdom of God.” Many Jews during the intertestamental period longed for such a society. Some Jews looked for an apocalyptic fulfillment of their kingdom hopes. They believed that God would miraculously intervene in history, punish corrupt rulers, and inaugurate a new age of justice under his appointed Messiah. The units in this theme trace developments during the intertestamental time, study the ministry and teachings of Jesus, and celebrate the resurrection as a powerful sign of the kingdom of God Unit 7: Setting the Scene for the Gospels Unit 8: A Christmas Peace Unit 9: The Ministry of Jesus Unit 10: The Teachings of Jesus Unit 11: The Easter Story Theme 3 / The Kingdom of God: Theme Introduction 226 Grade 6—Unit 7 Setting the Scene for the Gospels The writings of Isaiah, Zechariah, and others show that many Jews came back to Jerusalem from Babylon with high expectations of what life would be like in the restored community. The greatest hopes centered around a belief that God would bless Israel in new and miraculous ways. Perhaps now Israel truly would become the “kingdom of God” and a Messiah would lead Israel into a glorious era of peace and harmony.