The Power of Attraction in the Narrative of Soap Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tv Jockeys for Position in Digital-Marketing

www.spotsndots.com Subscriptions: $350 per year. This publication cannot be distributed beyond the office of the actual subscriber. Need us? 888-884-2630 or [email protected] The Daily News of TV Sales Thursday, April 25, 2019 Copyright 2018. TV JOCKEYS FOR POSITION IN DIGITAL-MARKETING AGE SCALE, EMOTION MAKE TV ‘THE MAIN DRIVER’ ADVERTISER NEWS Many digital markets claim TV is an ailing ad medium, but Ford Motor, in another move to shore up its electrification Bob Feinberg, vice president of Yonkers Honda in greater efforts, says it’s investing $500 million in electric vehicle New York City, says no way. “Discount (the influence) of TV startup Rivian and plans to build a battery EV using Rivian’s at your own peril,” he says, indicating many dealers like him flexible skateboard platform. The move comes weeks after consider television advertising alive and well and adapting talks between Rivian and General Motors reportedly broke to the digital age. down. GM reportedly was interested in becoming an equity He finds it ironic, Wards Auto reports, investor in Rivian, much like Amazon, that many digital enterprises nonetheless which invested $700 million in the startup advertise on TV. That group includes in February. For Ford, Automotive News Carvana, Google, Amazon and Netflix. reports, the deal secures another ally to Digital marketers who claim TV has lost manage costs and development in a hyper- power as an advertising outlet are flat- competitive space where it has so far lagged out wrong, contends Danielle DeLauro, behind much of the competition... Amazon executive vice president of the Video has started delivering packages inside Advertising Bureau. -

Dallas” in 2012 Ryan R

Watching & Waiting: “Dallas” in 2012 Ryan R. Sanderson “Bullets don’t seem to have much of an effect on me darlin’,” the old man calmly mutters. Of course we the audience know just what he means. No matter how old he might be—in character and in years—it’s a pleasure to be able to say: J.R. Ewing is back! And he still has it. There’s nothing like sitting down in front of a television here in 2012 to watch a new program that quickly proves not-so-new upon hearing that grand, wonderful, unmistakable theme music. It’s almost like a trip back in time—almost perhaps, though not. The nostalgia factor is obvious, at least to those of us who know the characters and all that’s happened with them and to them over the past 30+ years. To see most of them alive and relatively well satisfies our initial curiosity. After all, we’re tuning in to get reacquainted with our all-time favorites and be caught up on where they’ve been and just where their lives have come. We—that is the aforementioned “those of us” with sharp memories who know what’s going on—are the reason for the “return” of the world-famous show. Ultimately, we’re the ones who must be satisfied in order for the program to be a success. This said, I ask: Why am I largely disappointed thus far in the new “Dallas”? It’s not all bad; some strong moments are beginning to come through. -

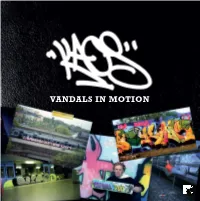

Vandals in Motion

KAOS “Kaos can be seen as a godfather of Swedish graffiti. IN MOTION VANDALS He’s been active since the 80s when he became famous for painting an incredible amount of train- pieces along with his crew VIM. Regrettably this is not only his past but also part of today’s reality.” – The CSG Anti-Graffiti Task Force VANDALS IN MOTION Torkel Sjöstrand Torkel ISBN: 978-91-85639-44-1 9 789185 639441 HIP HOP DON’T STOP Hip hop came to Europe in the early 80s, and when the films Beat Street and Style Wars were shown in 1984, the new youth culutre grew roots in Swedish urban areas. Hip hop was packaged with the four elements break- dancing, DJing, graffiti and rap, and was re- 4 UA Rockforce, Uppsala 1986 5 WILLROCK: That’s David’s KAOS KAOS boom box to the right and ceived with curiosity. But for the first genera- Ruskig breakdancing. He always had slightly bent tion of hip hoppers, the influences were few, knees when he was doing a windmill. and clothes, music and information hard to RUSKIG: I’m reading a comic book while doing a windmill. come by. In those days, we were pretty good at b-boying and battled Scare Crow, IC Rock- ers and other Stockholm gangs. Delight is in the background. VANDALS IN MOTION VANDALS IN MOTION Test, Hornstull, 1988 RUSKIG: When we did this one, I’d heard about other writers getting beaten up by the cops. On the sketch for the piece, I wrote “Policemen are nice”. -

2021 PISD Attendancezone M

G Paradise Valley Dr l e Ola Ln Whisenant Dr Lake Highlands Dr Harvest Run Dr Loma Alta Dr n Lone Star Ct 1 Miners Creek Rd 2 3 Robincreek Ln 4 5 W 6 R S 7 8 9 10 11 12 Halyard Dr a J A e o r g u Rivercrest Blvd O D s s Cool Springs Dr n C i n D Royal Troon Dr e n g Dr l t r Rivercrest Blvd r a Whitney Ct r c Moonlight T o a Hagen Dr l Dr D Fannin Ct t c e R C e R d u Blondy Jhune Trl y L r w m h Dr Stinson Dr Barley Plac D io D Fieldstone Dr l Rd Patagonian Pl w o r w P n en i e D a e l o i i l Autumn Lake Dr a l Warren Pkwy v a N Crossing Dr rv i f e n be idg Hunters l im R Frosted Green Ln L C Village Way T l w t M i h k n r r c e r r r c n e e r P n a Creek Ct D b e k d m w S l e h n i y L p t i u D 1 Rattle Run Dr k T L o r e M Burnet Dr f W r Daisy Dr r r Citrus Way G d Trl Timberbend r Austin Dr D o Artemis Ct o o a e e d y ac Macrocarpa Rd dl t Anns D d e Est r ak t e C W e Dr Legacy w onste Pebblebrook Dr d e o r C B Savann g r a Heather Glen Dr r ll r r R s a v D C d D D a i Hillcrest Rd a t Saint Mary Dr l h o o Braxton Ln D r w p b o i Wills Point Dr Oakland Hills Dr L r o Lake Ridge Dr ri k t Skyvie u 316 h R a i L C Way r L N White Porch Rd Dr y n O Knott Ct e s Rid Lime Cv i d n r g o e e d Katrina Path Aransas Dr Duval Dr n L k d Vidalia Ln Temp t s Co e Cir Citrus Way b t o e R ra D W M c ws i a r N Malone Rd R e W e n re t Kingswoo Blo e Windsor Rdg i e D r D t fo n o ndy Jhun B Dr Shallowater r N Watters Rd S l r til ra k Shadetree Ln s PLANO y L o r B z apsta R w a n Haystack Dr C n e d o Cutter Ln d w D Cedardale -

Number 156 Summer 2011 Price £3.50 “You Played Where??”

Number 156 Summer 2011 Price £3.50 “You played where??” PHOTO AND SCAN CREDITS Front Cover: Timis¸oara — see article inside — Paul Barnard Above: Bowood House, near Malmesbury — Alison Bexfield Inside Rear: Collecting Go IX: Badges — Tony Atkins UK News: photos from the Candidates Tournament and the London-Japan Friendship Match were kindly provided by Kiyohiku Tanaka. The remaining photos were kindly provided by the article authors. British Go Journal 156 Summer 2011 CONTENTS EDITORIAL 2 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 3 SERENDIPITY Roger Daniel 5 VIEW FROM THE TOP Jon Diamond 6 GOGOD RE-REVIEWED Francis Roads 7 DAVID WARD’S PROBLEM CORNER:PART 3 David Ward 9 UK NEWS Tony Atkins 10 THE MANY NAMES OF XU TONG-XI Guoru Ding 15 EYGC 2011 AT BRNO Paul, Roella and Kelda Smith 20 GAME REVIEW: EYGC 2011 Alexandre Dinerchtein 22 WORLD NEWS Tony Atkins 26 USEFUL WEB AND EMAIL ADDRESSES 27 BOOK REVIEW:THE CHINESE LAKE MURDERS Tony Atkins 28 TOURNAMENTS:TIME FOR CHANGE? Alison Bexfield 29 COUNCIL PROFILE:PAUL SMITH Paul Smith 31 DAVID WARD’S PROBLEM CORNER:HINTS David Ward 32 TONY ATKINS ON COUNTDOWN Tony Atkins 33 TIMIS¸OARA Paul Barnard 35 COUNCIL PROFILE:COLIN MACLENNAN Colin Maclennan 37 DAVID WARD’S PROBLEM CORNER:ANSWERS David Ward 38 SOLUTIONS TO THE NUMBERED PROBLEMS 39 COLLECTING GO IX: BADGES Tony Atkins — Rear Cover Copyright c 2011 British Go Association. Articles may be reproduced for the purposes of promoting Go and ‘not for profit’, providing the British Go Journal is attributed as the source and the permission of the Editor and of the authors have been sought and obtained in writing. -

Dallas (1978 TV Series)

Dallas (1978 TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the original 1978–1991 television series. For the sequel, see Dallas (2012 TV series). Dallas is a long-running American prime time television soap opera that aired from April 2, 1978, to May 3, 1991, on CBS. The series revolves around a wealthy and feuding Texan family, the Ewings, who own the independent oil company Ewing Oil and the cattle-ranching land of Southfork. The series originally focused on the marriage of Bobby Ewing and Pamela Barnes, whose families were sworn enemies with each other. As the series progressed, oil tycoon J.R. Ewing grew to be the show's main character, whose schemes and dirty business became the show's trademark.[1] When the show ended in May 1991, J.R. was the only character to have appeared in every episode. The show was famous for its cliffhangers, including the Who shot J.R.? mystery. The 1980 episode Who Done It remains the second highest rated prime-time telecast ever.[2] The show also featured a "Dream Season", in which the entirety of the ninth season was revealed to have been a dream of Pam Ewing's. After 14 seasons, the series finale "Conundrum" aired in 1991. The show had a relatively ensemble cast. Larry Hagman stars as greedy, scheming oil tycoon J.R. Ewing, stage/screen actressBarbara Bel Geddes as family matriarch Miss Ellie and movie Western actor Jim Davis as Ewing patriarch Jock, his last role before his death in 1981. The series won four Emmy Awards, including a 1980 Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series win for Bel Geddes. -

Deep in the Heart of Texas

Deep in the Heart of Texas written by Pamela McCaughey(2001), from an idea by Stephen Greaney based on the series "UFO" (1969-71) created by Gerry & Sylvia Anderson & Reg Hill and "Dallas", created by David Jacobs Warning: mild adult situations, some naughty words Chapter One July 1st, 1981, SHADO Headquarters, Great Britain "I've got the research you asked for on those oil lease properties in Texas, Ed," Alec Freeman threw himself into the seat across from Straker's desk, "Owned by one J.R. Ewing, residing in Dallas. Some big-name oil-baron." "Hmmp. Hope he's co-operative. If the reconnaissance photos are correct, we've got trouble brewing over there. Alien trouble," Straker paused to light one of his favourite cigarillos, "I want to send the Omega people in as quickly as possible." "What kind of alien activity is going on?" "We're not sure if it has anything to do with underground oil on those properties, or if there's some other mineral the aliens are after. You know how they love to get their hands on our natural resources." "Are the aliens actually trying to mine the area?" "If they are, it's all being done underground. Out of sight. Hush-hush. I doubt if Mr. Ewing is even aware he's got trespassers." "So how are you going to approach this?" "I guess the next step is to contact Mr. Ewing and buy those oil-leases - we don't want to tip him off to anything unusual, and if we can come to some sort of agreement, Omega can buy the properties and just carry on." ........a few hours later....... -

TIMES/NEWS/PAGES<11>

the times |Saturday June 92012 2GM 11 News Dallas born again with renewableenergyand less greed Swaggeringdisplays PAPICSELECT; CBS PHOTO ARCHIVE /GETTY IMAGES of extravagant wealth areout,but therivalry is as strongasever, writes Tim Teeman Rays of sun glint off afamiliar white- fronted house, iron gates marked “SF”, and —ifthe familiar twang of theme music hasn’t stirred your memory —a belt with a“JR” buckle. After a21-year absence (ignoring afew lamentable mini-series), Dallas returns to Amer- ican television on Wednesday as the children of JR and Bobby Ewing battle Not only are the characters different, for control of ...what else but Ewing so are the two eras of Dallas. The origi- Oil? Bobby groans to JR, “I don’t want nal was streaked with the Reaganite them to be like us,” but plus ça change. .. 1980s, the mythology of the Old West Despite the familiar Southfork whirl and unfettered capitalism reflected by of greed, jealousy and love triangles, the show. Today the rich lack the swag- producers promise aradically altered ger, at least on TV dramas: viewers are show from the Dallas of yore, which more used to seeing outrageous extrav- frothed so wildly that one season was agance on reality shows. Recession-era explained away as adream when America still likes stories of success, Patrick Duffy, who played Bobby, re- but overt greed is eyed balefully. turned to the show even though his Cynthia Cidre, writer and executive character had died. The revelation of producer, says that the new Dallas will “Who shot JR?” in 1980 (answer, Kris- The new Dallas features key actors from the 1980s cast, top right, but the storylines will reflect achanged America not “devolve into camp or cheap melo- tin Shepard) secured what was Amer- drama”, but be “a smart, passionate ica’s highest TV audience of 83 million spirit of nervy entrepreneurialism “Damn you JR”. -

2017 Grant Listing.Pdf

2017 Grant Recipients Exelon Corporation Exelon’s vision of providing superior value for our customers, employees and investors extends to the communities that we serve. In 2017, the Exelon family of companies provided over $44.9 million to non-profit organizations in the cities, towns and neighborhoods where our employees and customers live and work. In addition, the Exelon Foundation contributed over $7.1 million to communities Exelon serves. Exelon’s philanthropic efforts are focused on math and science education, environment, culture and arts and neighborhood development. Our employees’ efforts complement corporate contributions through volunteering and service on non-profit boards. Our employees volunteered 210,195 hours of community service in 2017. In addition, employees contributed a total of $11.84 million to the charity of their choice through the Exelon Foundation Matching Gifts Program and the Exelon Employee Giving Campaign. Exelon Corporation (NYSE: EXC) is a Fortune 100 energy company with the largest number of utility customers in the U.S. Exelon does business in 48 states, the District of Columbia and Canada and had 2017 revenue of $33.5 billion. Exelon’s six utilities deliver electricity and natural gas to approximately 10 million customers in Delaware, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania through its Atlantic City Electric, BGE, ComEd, Delmarva Power, PECO and Pepco subsidiaries. Exelon is one of the largest competitive U.S. power generators, with more than 32,700 megawatts of nuclear, gas, wind, solar and hydroelectric generating capacity comprising one of the nation’s cleanest and lowest-cost power generation fleets. -

Dallas As the Pinnacle of Human Evolutionary Television

Review of General Psychology © 2012 American Psychological Association 2012, Vol. 16, No. 2, 200–207 1089-2680/12/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0027915 Why Who Shot J. R. Matters: Dallas as the Pinnacle of Human Evolutionary Television Maryanne L. Fisher St. Mary’s University The TV series Dallas remains one of the most popular shows to ever have been broadcast on American TV. It was a serialized prime-time soap opera with weekly 45 minute episodes that ran from 1978 until 1991. This long-running show is one of the few to have been entirely released in DVD format; all 14 seasons are available as of 2011, and reruns are still aired internationally. Hundreds of thousands of visitors still tour the Southfork Ranch used for filming, outside Dallas, Texas. I will argue that the reason for this show’s success is because it routinely depicted themes that align with our evolved psychology. Using arguments that have been created to discuss literary Darwinism and gossip, I propose that this show depicted topics that have adaptive value; Dallas both exploits our evolved interests but also may act as a learning device for solving adaptive problems. Over the course of human evolution, it may have increased individual fitness to know who is wealthy or owns plentiful resources, has power and status, cheats on or poaches mates, engages in sibling rivalry, enhances their attractiveness, and so on. Dallas depicts these topics, and others, and thus, it is sensible that it would have been so successful among international audiences, and across decades. Keywords: mass media, evolution, TV, Dallas, prime time Why is it that so many TV shows seem to have the same basic manner, it begs the question of why that specific type of show is content? At the moment, one of my favorite shows is Castle. -

CONSENT JUDGMENT and PERMANENT INJUNCTION By

Warner Bros Home Entertainment Inc v. Valerie Herrera et al Doc. 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 ) 12 Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Inc., ) Case No. CV13-4059 JAK (JCx) ) 13 Plaintiff, ) CONSENT DECREE AND ) PERMANENT INJUNCTION 14 v. ) ) JS-6 15 ) Valerie Herrera a/k/a Valerie Lee, an ) 16 individual and d/b/a as Amazon.com ) Seller Sirena0123, Irvin Y. Lee, an ) 17 individual and d/b/a Amazon.com Seller ) Sirena0123 and Does 2-10, inclusive, ) 18 ) Defendants. ) 19 ) ) 20 21 The Court, having read and considered the Joint Stipulation for Entry of 22 Consent Decree and Permanent Injunction that has been executed by Plaintiff Warner 23 Bros. Home Entertainment Inc. (“Plaintiff”) and Defendants Valerie Herrera a/k/a 24 Valerie Lee, an individual and d/b/a as Amazon.com Seller Sirena0123 and Irvin Y. 25 Lee, an individual and d/b/a Amazon.com Seller Sirena0123 (collectively 26 “Defendants”), in this action, and good cause appearing therefore, hereby: 27 /// 28 /// Warner Bros. v. Herrera: Consent Decree - 1 - Dockets.Justia.com 1 ORDERS that based on the Parties’ stipulation and only as to Defendants, their 2 successors, heirs, and assignees, this Injunction shall be and is hereby entered in the 3 within action as follows: 4 1) This Court has jurisdiction over the parties to this action and over the subject 5 matter hereof pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., and 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338. 6 Service of process was properly made against Defendants. -

CUCSSN80600002.Pdf (7.409Mb)

Physics Degree Approved by CCHE A bachelor of science degree Ronald R. Bourassa, chairman in physics will be offered for the of the department. first time in September at In addition to preparing stu uccs, according to Chancellor dents who intend to pursue Donald Schwartz_ graduate studies in physics or to. Announcement of the new seek an industrial position with degree followed approval July a traditional physics degree, 11 of the program by the Colo two special options will be rado Commission on Higher offered, he said. ' ' Education, which has final The Applied Physics, or Solid authority over proposed degree State, option will be for students programs for the state's public presently employed or who colleges and universities. intend to seek employment in' The physics degree will be the semi-conductor industry. offered by the Department of' The Energy Science option Physics and Energy Science win prepare students, for through the College of Letters, energy-related careers in indus- , Arts and Sciences. This brings try and government. to 16 the num'ber of degree pro The new degree program was grams available through LAS. approved by the university's Bats Invade Main Hall Three options will be avail board of regents in March, prior able to students who will major to its submission to the CCHE. by Mike Hackman came back negative, none of the voked. "They show their teeth in physics, according to Dr. Why is everyone in Main Hall bats' were rabid. "If someone is and let out a hiss when we try to looking skyward? Divine gui bitten or comes in contact with a capture them," Trujillo inter dance? No! Bats.