KENHAT, the DIALECTS of UPPER LADAKH and ZANSKAR1 According to Phonetic Features Alone, the Various Dialects Spoken in Ladakh Ar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnobotany of Ladakh (India) Plants Used in Health Care

T. Ethnobivl, 8(2);185-194 Winter 1988 ETHNOBOTANY OF LADAKH (INDIA) PLANTS USED IN HEALTH CARE G. M. BUTH and IRSHAD A. NAVCHOO Department of Botany University of Kashmir Srinagar 190006 India ABSTRACf.-This paper puts on record the ethnobotanical information of some plants used by inhabitants of Ladakh (India) for medicine, A comparison of the uses of these plants in Ladakh and other parts of India reveal that 21 species have varied uses while 19 species are not reported used. INTRODUCTION Ladakh (elev. 3000-59G(}m), the northernmost part of India is one of the most elevated regions of the world with habitation up to 55(}(}m. The general aspect is of barren topography. The climate is extremely dry with scanty rainfall and very little snowfall (Kachroo et al. 1976). The region is traditionally rich in ethnic folklore and has a distinct culture as yet undisturbed by external influences. The majority of the population is Buddhist and follow their own system of medicine, which has been in vogue for centuries and is extensively practiced. It offers interesting insight into an ancient medical profession. The system of medicine is the"Amchi system" (Tibetan system) and the practi tioner, an"Amchi." The system has something in common with the "Unani" (Greek) and"Ayurvedic" (Indian) system of medicine. Unani is the traditional system which originated in the middle east and was followed and developed in the Muslim world; whereas the Ayurvedic system is that followed by Hindus since Rig vedic times. Both are still practiced in India. Though all the three systems make USe of herbs (fresh and dry), minerals, animal products, etc., the Amchi system, having evolved in its special environment, has its own characteristics. -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

Endangered Oral Tradition in Zanskar Valley

Stanzin Dazang Namgail ENDANGERED ORAL TRADITION IN ZANSKAR VALLEY MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection ENDANGERED ORAL TRADITION IN ZANSKAR VALLEY by Stanzin Dazang Namgail (India) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2019 ENDANGERED ORAL TRADITION IN ZANSKAR VALLEY by Stanzin Dazang Namgail (India) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2019 CEU eTD Collection ENDANGERED ORAL TRADITION IN ZANSKAR VALLEY by Stanzin Dazang Namgail (India) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of -

Himalayan Journal of Sciences Vol 2 Issue 4 (Special Issue) July 2004

EXTENDED ABSTRACTS: 19TH HIMALAYA-KARAKORAM-TIBET WORKSHOP, 2004, NISEKO, JAPAN Biostratigraphy and biogeography of the Tethyan Cambrian sequences of the Zanskar Ladakh Himalaya and of associated regions Suraj K Parcha Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, 33 - Gen. Mahadeo Singh Road, Dehra Dun -248 001, INDIA For correspondence, E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... The Cambrian sections studied so far exhibit 4 km thick and North America Diplagnostus has been reported from the Lejopyge apparently conformable successions of Neoproterozoic and laevigata Zone which characterizes the latest Middle Cambrian. Cambrian strata in Zanskar - Spiti basins. The Cambrian In the Lingti valley of the Zanskar area the presence of Lejopyge sediments of this area are generally fossiliferous comprising sp. is also of stratigraphic importance as it underlies the trilobites, trace fossils, hylothids, cystoids, archaeocythid and characteristic early Late Cambrian faunal elements. In the Magam brachiopod, etc. In parts of Zanskar – Spiti and Kashmir region section of Kashmir the Diplagnostus occurs at the top of the rich trilobite fauna is collected from the Cambrian successions. Shahaspis (=Bolaspidella) Zone of Jell and Hughes (1997), that is The trilobites constitute the most significant group of fossils, overlain by the Damesella Zone, which contains characteristic which are useful not only for the delimination of various biozones faunal elements of Changhian early Late Cambrian age. The but also for the reconstruction of the Cambrian paleogeography genus Damesella is also reported from the Kushanian stage in of the region. China, the Tiantzun Formation in Korea and from Agnostus The Zanskar basin together with a part of the Spiti basin pisiformis Zone of the Outwood Formation in Britain. -

China and Kashmir* Buildup Along the Indo-Pak Border in 2002 (Called Operation Parakram in India)

China and Kashmir* buildup along the Indo-Pak border in 2002 (called Operation Parakram in India). Even if the case may by JABIN T. Jacob be made that such support to Pakistan has strength- ened Pakistan’s hands on the Kashmir dispute, it is difficult to draw a direct link between the twists and turns in the Kashmir situation and Chinese arms supplies to Pakistan. Further, China has for over two Perceptions about the People’s Republic of China’s decades consistently called for a peaceful resolution position on Kashmir have long been associated with of the Kashmir dispute, terming it a dispute “left over its “all-weather” friendship with Pakistan. However, from history.” Both during Kargil and Operation the PRC’s positions on Kashmir have never been Parakram, China refused to endorse the Pakistani consistently pro-Pakistan, instead changing from positions or to raise the issue at the United Nations. disinterest in the 1950s to open support for the Paki- Coupled with rising trade and the continuing border stani position in the subsequent decades to greater dialogue between India and China, this has given rise neutrality in the 1980s and since. While China has to hopes in India that the Kashmir dispute will no China’s positions on continued military support to Pakistan even during longer be a card the Chinese will use against it. Kashmir have never been military conflicts and near-conflicts between India and Pakistan, its stance on Kashmir has shifted consistently pro-Pakistan, gradually in response to the prevailing domestic, China and Pakistan Occupied Kashmir instead changing from dis- regional, and international situations. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum. -

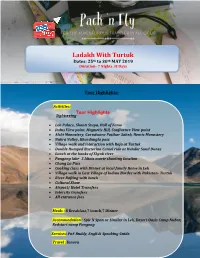

Ladakh with Turtuk Dates: 25Th to 30Th MAY 2019 Duration- 7 Nights /8 Days

Ladakh With Turtuk Dates: 25th to 30th MAY 2019 Duration- 7 Nights /8 Days Tour Highlights: Activities: Tour Highlights Sightseeing • Leh Palace, Shanti Stupa, Hall of Fame • Indus View point, Magnetic Hill, Confluence View point • Alchi Monastery, Gurudwara Patthar Saheb, Hemis Monastery • Nubra Valley, Khardungla pass • Village walk and interaction with Raja at Turtuk • Double Humped Bacterian Camel ride at Hunder Sand Dunes • Lunch at the banks of Shyok river • Pangong lake- 3 Idiots movie shooting location • Chang La Pass • Cooking class with Dinner at local family Home in Leh • Village walk in Last Village of Indian Border with Pakistan- Turtuk • River Rafting with lunch • Cultural Show • Airport/ Hotel Transfers • Intercity transfers • All entrance fees Meals : 8 Breakfast,7 Lunch,7 Dinner Accommodation : Spic N Span or Similar in Leh, Desert Oasis Camp Nubra, Redstart camp Pangong Services: PnF Buddy, English Speaking Guide. Travel : Innova What makes you choose Ladakh as your ‘ME’ time Destination Few places in India are at once so traveler-friendly and yet so enchanting and hassle-free as mountain- framed Leh. Dotted with stupas and whitewashed houses, the Old Town is dominated by a dagger of steep rocky ridge topped by an imposing Tibetan-style palace and fort. Beneath, the bustling bazaar area is draped in a thick veneer of tour agencies, souvenir shops and tandoori-pizza restaurants, but a web of lanes quickly fans out into a green suburban patchwork of irrigated barley fields. Here, gushing streams and narrow footpaths link traditionally styled Ladakhi garden homes that double as charming, inexpensive guesthouses. Leh’s a place that’s all too easy to fall in love with – but take things very easy on arrival as the altitude requires a few days' acclimatization before you can safely start enjoying the area's gamut of adventure activities. -

`15,999/-(Per Person)

BikingLEH Adventure 06 DAYS OF THRILL STARTS AT `15,999/-(PER PERSON) Leh - Khardungla Pass - Nubra Valley - Turtuk - Pangong Tso - Tangste [email protected] +91 9974220111 +91 7283860777 1 ABOUT THE PLACES Leh, a high-desert city in the Himalayas, is the capital of the Leh region in northern India’s Jammu and Kashmir state. Originally a stop for trading caravans, Leh is now known for its Buddhist sites and nearby trekking areas. Massive 17th-century Leh Palace, modeled on the Dalai Lama’s former home (Tibet’s Potala Palace), overlooks the old town’s bazaar and mazelike lanes. Khardung La is a mountain pass in the Leh district of the Indian union territory of Ladakh. The local pronunciation is "Khardong La" or "Khardzong La" but, as with most names in Ladakh, the romanised spelling varies. The pass on the Ladakh Range is north of Leh and is the gateway to the Shyok and Nubra valleys. Nubra is a subdivision and a tehsil in Ladakh, part of Indian-administered Kashmir. Its inhabited areas form a tri-armed valley cut by the Nubra and Shyok rivers. Its Tibetan name Ldumra means "the valley of flowers". Diskit, the headquarters of Nubra, is about 150 km north from Leh, the capital of Ladakh. Turtuk is one of the northernmost villages in India and is situated in the Leh district of Ladakh in the Nubra Tehsil. It is 205 km from Leh, the district headquarters, and is on the banks of the Shyok River. Pangong Tso or Pangong Lake is an endorheic lake in the Himalayas situated at a height of about 4,350 m. -

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ Laurianne Bruneau & John Vincent Bellezza I. An introduction to the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh his paper examines common thematic and esthetic features discernable in the rock art of the western portion of the T Tibetan plateau.1 This rock art is international in scope; it includes Ladakh (La-dwags, under Indian jurisdiction), Tö (Stod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang, under Chinese administration) hereinafter called Upper Tibet. This highland rock art tradition extends between 77° and 88° east longitude, north of the Himalayan range and south of the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains. [Fig.I.1] This work sets out the relationship of this art to other regions of Inner Asia and defines what we call the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’. The primary materials for this paper are petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings). They comprise one of the most prolific archaeological resources on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Although pictographs are quite well distributed in Upper 1 Bellezza would like to heartily thank Joseph Optiker (Burglen), the sole sponsor of the UTRAE I (2010) and 2012 rock art missions, as well as being the principal sponsor of the UTRAE II (2011) expedition. He would also like to thank David Pritzker (Oxford) and Lishu Shengyal Tenzin Gyaltsen (Gyalrong Trokyab Tshoteng Gön) for their generous help in completing the UTRAE II. Sponsors of earlier Bellezza expeditions to survey rock art in Upper Tibet include the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) and the Asian Cultural Council (New York). -

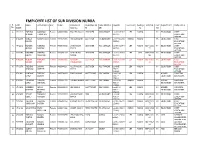

Employee List of Sub Division Nubra S

EMPLOYEE LIST OF SUB DIVISION NUBRA S. EMP Name Father Name Sex Mobile Permanent DESIGNATIO POSTINGPLA Payscale Home Ac Posting EPICNO DEP Department CODETAILS No. CODE Address N CE Ac AS 1 0701212 TSERING KONCHOK Female 9469509399 TIA LEH 194101 LECTURER GHSS DISKIT Level-9 (52700- LEH NUBRA P0 EDUCATION CHIEF CHOROL THANCHEN 166700) EDUCATION OFFICER 2 0702669 KUNZES SONAM TASHI Female 9419979316 HSS BOGDANG LECTURER HS BOGDANG Level-9 (52700- NUBRA NUBRA P0 EDUCATION CHIEF DOLMA 166700) EDUCATION OFFICER 3 0702212 NORZIN TSERING Female 9419878868 SANKAR LEH LECTURER HSS SUMOOR Level-9 (52700- LEH NUBRA BBF02216 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF ANGMO NAMGAIL 194101 166700) 71 EDUCATION OFFICER 4 0702240 RINCHEN TSERING Female 9419851117 NYAKCHUNG LECTURER HSS SUMOOR Level-9 (52700- LEH LEH BBF04726 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF DOLMA ANGCHOK NIMOO 166700) 96 EDUCATION OFFICER 5 0702238 RUBINA RAMZAN Female 9419982912 KOTIDAR LECTURER HSS SUMOOR Level-9 (52700- LEH NUBRA BBF04119 P0 EDUCATION CHIEF KAUSAR KHAN CHOKLAMSAR 166700) 18 EDUCATION OFFICER 6 0701378 TSERING SONAM Female 9419344280 HSS TYAKSHI LECTURER HSS TYAKSHI Level-6E LEH NUBRA P0 EDUCATION CHIEF CHONDOL CHEPHEL 194401 (35900- EDUCATION 113500) OFFICER 7 0701601 KUNZANG TSERING Female 9469736429 TINGMOGANG ASSTT PROF GDC NOBRA Level-10A LEH NUBRA P0 HIGHER PRINCIPAL LAMO DORJAY (56600- EDUCATION GDC NUBRA 179800) 8 0701607 TSEWANG TSERING Female 9469527400 HUNDER NOBRA ASSTT PROF GDC NOBRA Level-10A NUBRA NUBRA P0 HIGHER PRINCIPAL LAMO WANGAIL (56600- EDUCATION GDC NUBRA 179800) 9 0701618 SAMEENA -

Village Ralakung Geographic Location

Expedition to Electrify - Village Ralakung Geographic Location Zanskar Expedition Route Map Facts – Village Ralakung • 1200 Year Old Village nestled in the Phe block of Zanskar (Himalayas) • The most remotest & backward village of the region • Village home to 110 people and 11 Households • Village Divided into two Parts – Phema and Nagma • Village remains cut off for 7 months due to snowfall blocking passes • Accessed by helicopters for purpose of medical evacuation and voting • Known for rich minerals and natural resources • The Region is also known for Unique Volcanic Igneous rock formation • There is one primary school in the village with 8 students • Only one Satellite Phone in the village to connect with outside world • The Village doesn't have a single person who is a graduate Accessibility in Winters • Ralakung is cut off from the rest of the world for 7 months. • Can only be accessed by walking on the Frozen River for 8 days Accessibility in Winters Overall Expedition Journey- 900 KMS • 2 Days by Vehicular Journey Leh To Kargil Kargil to Phe • Total Vehicular Distance – 860 Kms (To and Fro) • 2 Days of Trekking in the Valley One side trekking distance – 45 Kms (To and Fro) • 6 Nights of Camping/Homestays in Villages • Horses carrying Solar Micro- grid material Average Altitude of Journey – 13400 ft Highest Mountain Pass During journey- 15400 Ft Trekking-40 Kms 3 days of Continuous trekking. Camping at 13000 ft. Crossing a mountain pass at 5300m Ralakung Village The remotest village of the region Of Zanskar • Hardly 40 -50 tourists have come here • Not even .01% of Ladakh has reached this village People and Houses of Ralakung 11 Households and more than 130 People Solar Micro Grid Installation Day One: You will fly into Leh from New Delhi.