NRPPD 22.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darjeeling 2020-21

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN DARJEELING 2020-21 Government of West Bengal Office of District Magistrate, Darjeeling Department Of Disaster Management Tel/Fax No. : 0354-2255749 Email id.: [email protected] INDEX PAGE NOS. NOS. CONTENTS Emergency Control Numbers 1. CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 1-4 1.1 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 1 1.2 AUTHORITY FOR DDMP 1 1.3 EVOLUTION OF DDMP 2 1.4 STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR RESPONSIBILITIES 3 1.5 HOW TO USE DDMP 3 1.6 APPROVAL MECHANISM OF DDMP 4 1.7 REVIEW AND UPDATEN OD D.D.M.P 4 2. CHAPTER II – DISTRICT HAZARD RISK VULNERABILITY AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT 5-27 (HRVCA) 2.1 DISTRICT PROFILE (GEOGRAPHICAL, ADMINISTRATIVE AND DEMOGRAPHIC) 5 a District Landuse/Landcover Map 7 b District Geological Map 8 c District Administrative Map 9 d District Mp of Transpot Lines 10 e District Map of Settlements 11 2.2 HAZARD PROFILE 12 2.3 (i) AREAS AFFECTED BY CALAMITY (2019) 13-15 Monsoon Calamity Assessment Report (2019) 16 2.3 (ii) AREAS AFFECTED BY CALAMITY (2018) 17-21 2.4 INVENTORY OF PAST DISASTERS 20-23 2.5 HVRCA ACROSS THE FOUR SUBDIVISIONS 26-27 3. CHAPTER III - INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR DISASTER MANAGEMENT 28-32 3.1 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY 28 3.2 FUNCTIONAL FLOW AND HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE OF AUTHORITIES AND COMMITTEES 29 3.3 POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF DDMA 29-31 3.4 STRENGTHENING DDMA 32 4. CHAPTER IV - PREVENTIVE MITIGATION MEASURES 33-34 4.1 PREVENTIVE MEASURES ADOPTED AT EACH BLOCK 33 4.2 DISTRICT LEVEL MITIGATION PROJECTS UNDER NATIONAL LEVEL 34 4.3 PREVENTIVE GUIDELINES OF N.D.M.A FOR HEALTH EMERGENCIES – COVID-19 PANDEMIC 34 5. -

Synopsis on Survey of Tea Gardens Conducted by Regional Labour Offices Under Jurisdiction of Joint Labour Commissioner, North Bengal Zone Contents

Synopsis on Survey of Tea Gardens Conducted by Regional Labour Offices under jurisdiction of Joint Labour Commissioner, North Bengal Zone Contents Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Introduction : …………………………………………. 2 to 3 2. Particulars of Tea Estates in North Bengal : …………………………………………. 4 to 5 3. Particulars of Employers (Management) : …………………………………………. 6 to 7 4. Operating Trade Unions : …………………………………………. 8 to 9 5. Area, Plantation & Yield : …………………………………………. 10 to 11 6. Family, Population, Non-Workers & Workers in Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 12 to 14 7. Man-days Utilized : …………………………………………. 15 to 15 8. Production of Tea : …………………………………………. 16 to 17 9. Financial & Other Support to Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 18 to 18 10. Housing : …………………………………………. 19 to 21 11. Electricity in Tea Estates : …………………………………………. 22 to 22 12. Drinking Water in Tea Estates : …………………………………………. 23 to 23 13. Health & Medical Facilities : …………………………………………. 24 to 24 14. Labour Welfare Officers : …………………………………………. 25 to 25 15. Canteen & Crèche : …………………………………………. 26 to 26 16. School & Recreation : …………………………………………. 27 to 27 17. Provident Fund : …………………………………………. 28 to 29 18. Wages, Ration, Firewood, Umbrella etc. : …………………………………………. 30 to 30 19. Gratuity : …………………………………………. 31 to 32 20. Bonus Paid to the Workmen of Tea Estate : …………………………………………. 33 to 33 21. Recommendation based on the Observation of Survey : …………………………………………. 34 to 38 Page 1 of 38 INTRODUCTION Very first time in the history of tea industry in North Bengal an in-depth survey has been conducted by the officers of Labour Directorate under kind and benevolent guardianship of Shri Purnendu Basu, Hon’ble MIC, Labour Department, Government of West Bengal and under candid and active supervision of Shri Amal Roy Chowdhury, IAS, Secretary of Labour Department (Labour Commissioner at the time of survey), Govt. -

CERES JAS Client List 2021 (Updated on June 04, 2021)

CERES JAS client list 2021 (updated on June 04, 2021) 2018 2018 2019 2019 2020 2020 2021 2021 Date of Date of Date of Date of PPM/Re crop/wi Proces Cert. N° Cert. N° Cert. N° Cert. N° Comment (e.g. reason of Name of operation Country Address of Client Name of operation sites addresses of operation sites certificate certificate certificate certificate -Packer co sing 2018 2019 2020 2021 suspension / revocation) issue issue issue issue 10 Kapitan leitenant Evstati ①Aroniada-Agro ЕOOD ①3 Carkovna nezavisimost Str., Aroniada-Agro EOOD BG Vinarov str, 7000 Ruse, Bulgaria ②Kristina Kalinova 7000 Ruse, Bulgaria PPM x 16.04.2019 46064-2 09.04.2020 46064-3 ②23 Baba Tonka Str., 7150 Dve 10 Kapitan leitenant Evstati Agrobiotech Ltd v.mogili, Enina, Bulgaria Kazanlak district, Stara Aroniada-Agro EOOD BG Vinarov str, 7000 Ruse, Bulgaria Zagora region, Bulgaria PPM x 16.04.2019 46064-2 09.04.2020 46064-3 Av. 6 de Marzo, Calle 5 #55, Zona BV 082, BV 1061, BV 500, BV LOAYZA, COPACABANA, AGRICABV/AGRICAFE S.A. BO Santa Rosa, El Alto, La Paz, 1062 etc. (see Annex) INCAPAMPA, SAN PABLO II etc. PPM x 12.10.2018 36271-2 20.08.2019 36271-3 11.11.2020 36271-4 Bolivia. (see Annex) Av. 6 de Marzo, Calle 5 #55, Zona Planta de Beneficio Ecológico Colonia Corpus Christy S/N, AGRICABV/AGRICAFE S.A. BO Santa Rosa, El Alto, La Paz, Municipio Caranavi, La Paz, Bolivia PPM x 12.10.2018 36271-2 20.08.2019 36271-3 11.11.2020 36271-4 Bolivia. -

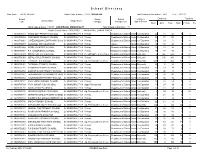

S C H O O L D I R E C T O

S c h o o l D i r e c t o r y State Name : WEST BENGAL District Code & Name : 1901 DARJILING Total Schools in this district : 1521 Year : 2011-12 School School School Location & Enrolment Teachers Code School Name Village Name Category Management Type of School Boys Girls Total Male Female Total Block Code & Name: 190137 DARJEELING_MUNICIPALITY Total Schools in this block : 71 Cluster Code & Name: 1901370001 DARJEELING_URBAN_CIRCLE 1 19013700801 WARD NO 7 PRIMARY SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 9 Department of EducationUrban Co-Educational 22 18 40 3 3 2 19013702902 CONGRESS PRIMARY SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 1 Department of EducationUrban Co-Educational 54 48 102 2 4 3 19013702901 JOREBUNGLOW S M PRIMARY SCHOOLDJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 1 Department of EducationUrban Co-Educational 22 29 51 1 4 4 19013702903 KATAWALI SSK JALAPAHAR DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 1 Others Urban Co-Educational 16 10 26 0 2 5 19013700902 NAVIN GRAM PRY SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 11 Department of EducationUrban Co-Educational 18 18 36 2 1 6 19013700901 R K JUNIOR BASIC SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 11 Department of EducationUrban Co-Educational 43 47 90 1 3 7 19013701003 NEPALI GIRLS H S SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPr. with NO Up.Pr.12 & sec./H.Sec. Department of EducationUrban Girls only 0 645 645 0 36 8 19013701004 NEPALI GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDPrimary NO 12 Department of EducationUrban Girls only 0 436 436 0 17 9 19013701002 TURNBULL H S SCHOOL DJ MUNICIPALITY WARDUp. PrimaryNO 12 with sec./H.sec -

Dissertation Submitted to the Sikkim University in Partial Fulfillment of the Award of the Degree Of

PLANTATION INDUSTRY OF DARJEELING REGION: A HISTORICAL STUDY Dissertation Submitted to the Sikkim University in Partial Fulfillment of the Award of The Degree of MASTERS OF PHILOSOPHY Submitted by SUSHMA RAI Supervised by Ms. SANGMU THENDUP Assistant Professor Department of History School of Social Sciences Sikkim University Sikkim 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the very outset, I feel proud to express my deep sense of gratitude to my Supervisor, Ms. Sangmu Thendup for her guidance in shaping my research imagination and constant help and inspiration in every step for preparation of my dissertation in spite of her busy schedule. She indeed, remained an unfailing source of strength, inspiration and guidance in completing my work. I am greatly obliged to my H.O.D Dr. V. Krishna Ananth and the rest of the faculty members of History Department, Sikkim University for their help and support, without which this work would have not been possible. I am thankful to the authorities and staff of Central Library of Sikkim University, Darjeeling District Library, Libraries at North Bengal University, Centre of Himalayan Studies (N.B.U), Southfield College, Salesian College, Darjeeling Government College, National Library, Kolkata and Asiatic Society, Kolkata for providing access to the rare books, Journals and articles for my present study. I would also like to thank the office staffs of Indian Tea association, Darjeeling Tea Association, Darjeeling Planters’ Club, Tea Board of India, Directorate of Cinchona and Other Medicinal Plants, Darjeeling Municipality and Kutchery, Darjeeling. This work would not have been possible without the help and support of my parents and my sister. -

WWF-India Published in September 2013 by WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund), Darjeeling, India

REPORT IND 2012 Annual Activity Report 2012 "Save the Environment and Regenerate Vital Employment" (Project SERVE), Darjeeling A joint initiative of Projektwerkstatt Teekampagne-Germany and WWF-India Published in September 2013 by WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund), Darjeeling, India. Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. Designed by: Aspire Design, New Delhi © WWF-India All rights reserved Front cover photo: © Deependra Sunar / WWF-India ii Annual Activity Report 2012 "Save the Environment and Regenerate Vital Employment" (Project SERVE), Darjeeling A joint initiative of Projektwerkstatt Teekampagne-Germany and WWF-India iii © SANJEEB PRADHAN / WWF-INDIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Vii Project Area Profi le 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Project Objectives 2 3. Activities 5 3.1. Ecological Restoration 5 3.1.1. Block Forest Plantation (BFP) 6 3.1.2. Shade Tree Plantation in Tea Gardens of Darjeeling Hills 8 3.1.3. Soil conservation at landslide affected areas 10 3.1.4. Training and distribution of bio-globule (briquette) molding machines 10 3.1.5. Conservation of Rhododendron species 11 3.1.6. Biodiversity study of tea gardens in Darjeeling Hills 11 3.1.7. Nursery raising training at Chamong and Chatakpur 13 3.2. Livelihood & Income Generation Activities: 14 3.2.1. Apiculture training and workshop 14 3.2.2. Sapling raising in Project SERVE nurseries 15 3.2.3. Participation at agriculture fair 16 3.2.4. Mushroom cultivation 16 3.2.5. Vermi composting 17 3.3 Environment Education & Awareness 18 3.3.1. -

Annual Activity Report 2015-2016

2018 ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2015-2016 PROJECT SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT AND REGENERATE VITAL EMPLOYMENT (PROJECT SERVE), DARJEELING A JOINT INITIATIVE OF PROJEKTWERKSTATT TEEKAMPAGNE-GERMANY AND WWF-INDIA Published by WWF-India, Darjeeling Field Office Khangchendzonga Landscape Programme Table of Contents 1. Foreword...............................................................................................................................5 2. Area Profile............................................................................................................................6 3. Introduction..........................................................................................................................9 4. Project Vision, Goals and Objectives...................................................................................11 5. Project Activities..................................................................................................................13 Goal 1- Conserve key species, wildlife habitats and priority wetlands..............................13 Goal 2- Build climate resilient communities through appropriate livelihood interventions.......................................................................................................................18 Goal 3- Greening young minds to build a future constituency for conservation..............19 Copyright © WWF-India 2018 WWF-India 172-B, Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110 003 Tel: +91 11 4150 4814 Website: www.wwfindia.org Published by WWF-India Any reproduction in full -

Himalya in Sikkim 1

Ervaar het dorpsleven en de prachtige Himalaya gebergte in Sikkim. Kolkata - Darjeeling - Sikkim 12 dagen / 11 nachten Deze 12 daagse reis brengt je naar het Bengalese Sikkim gebied. Naast de prachtige Himalaya gebergte ontmoet je de dorpsbewoners in verschillende Himalaya dorpjes. Je trekt langs thee tuinen en overnacht je bij een locale familie thuis, waar je de traditionele gerechten van de streek kunt proeven. Je wandelt in het hoogste deel van Bengalen (langs de Indo Nepal-grens) om het magische landschap met de hoogste bergen te zien. Deze reis kenmerkt zich door een mooie afwisseling van cultuur en natuur. Dag 1 || Kolkata aankomst Bij je aankomst op het vliegveld van Kolkata word je welkom geheten en naar je hotel gebracht. Er zal een korte uitleg zijn over de stad Kolkata en hoe de reis er verder uit gaat zien. Afhankelijk van het tijdstip dat je aankomt kun je de stad alvast wat verkennen of bijkomen op je hotelkamer. (Optioneel) Zonsondergangcruise van 16.00 uur tot 19.00 uur met tempelbezoek. Een cruise over de Ganges is de beste manier om de stad en haar geschiedenis te verkennen. De boot brengt je naar Belur math om daar de Sandhya Aarti te zien. Een aarti is een vuurceremonie waarbij prachtige mantras worden gezongen. Geniet van deze prachtige mantras aan boord onder een genot van een drankje, terwijl je onder de mooi verlichte Howrah brug door vaart. Je overnacht in Kolkatta. Dag 2 || Volledige dag in Kolkata - rondleiding en een proeverij Na het ontbijt start er een rondleiding door de oude stad. Kolkata was ooit het centrum van de moderne Indiase onderwijs, wetenschap, cultuur en politiek. -

Draft Tea Directory

North India - List of Tea Gardens covered in Baseline Survey, 2018 Status of the RC number Present estate under TMCO (if Name of the installed Status of the S. No Name of the Estate State Regd. No. (Functional/ the estate owns Owners/ Company/ capacity Company Project garden/ a manufacturing Patnership Firms (kgs/annum) Closed etc) unit) ARUNACHAL 1 ABALI TEA ESTATE NEGB-9 Functional RC-1955 50000 Proprietorship JATON PULU PRADESH RAJA ROY, B.R. TEA 2 AARAKAN TEA ESTATE WEST BENGAL Project Garden Public Ltd Co PVT. LTD. Private Limited ABHOYJAN TEA 3 ABHOYJAN TEA ESTATE ASSAM 82 Functional RC-1504 1200000 Company COMPANY PVT LTD Private Limited 4 ACHABAM ASSAM A 58 Functional RC-154 1400000 Company 5 ADARANI TEA ESTATE TRIPURA 693 Functional Proprietorship SUJOY CHOUDHURY MCLEOD RUSSEL INDIA 6 ADDABARIE ASSAM N 24 Functional RC 216 1500000 Public Ltd Co LIMITED Private Limited BHUWALKA TRADING 7 AENAKHALL T.E. ASSAM 2471 Functional RC-1282 1800000 Company & TEA CO.PVT. LTD. Partnership AGARWAL TEA ESTATE 8 AGARWAL ASSAM 2715 Functional firm (PARTNERSHIP FIRM) MOHAN KR. GOENKA, Partnership 9 AHMEDY TEA ESTATE ASSAM 336 Functional MUKESH KR. GOENKA, firm DINDAYAL BAGRODIA 2200000 Private Limited GOODRICKE GROUP 10 AIBHEEL TEA GARDEN WEST BENGAL B-81 Functional KGS/ANNUM Company LIMITED Private Limited THENGALBARI ESTATES 11 AIDEOBARI TEA ESTATE ASSAM 2124 Functional RC-1192 1500000 Company PVT LTD AIDEOPUKHURI TEA Private Limited 12 ASSAM 1065 Functional NITI BANRAH ESTATE Company AIRAN PLANTATION (P) Private Limited AIRAN PLANTATION (P) 13 WEST BENGAL Functional LTD Company LTD 14 AKHOIDESSA TEA ESTATE ASSAM 375 Functional Proprietorship J.N. -

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3633 (H) to BE ANSWERED on 17Th MARCH, 2021

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE) LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3633 (H) TO BE ANSWERED ON 17th MARCH, 2021 TEA GARDENS 3633 (H). SHRI NABA KUMAR SARANIA: Will the Minister of COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (वािण�य एवं उ�ोग मं�ी) be pleased to state: (a) the total number along with the total area of tea gardens in the country, the details and the names thereof; (b) whether any subsidy is being given by the Government to tea companies and if so, the time by when the daily wages of the labourers are likely to be brought at par with the national parameters as daily wage of the labourers working in tea gardens is Rs.167/-; (c) whether minimum wages does not apply on labourers working in tea gardens and if so, the details thereof; (d) the details of the facilities provided by the company to labourers working in tea gardens; and (e) the details of the profit made by the various tea garden companies during the last three years and the details of the funds spent from CSR fund during thelast five years? ANSWER okf.kT; ,oa m|ksx ea=ky; esa jkT; ea=h ¼Jh gjnhi flag iqjh½ THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (SHRI HARDEEP SINGH PURI) (a) There are 1569 tea gardens in the country with a total tea area of 420671 Ha. The details of tea gardens with names are given in Annexure-I . (b)& (c): The Central Government through the Tea Board is implementing “Tea Development and Promotion Scheme (TDPS)’’ for development of the Tea Sector. -

Sl. No. Exporter Name Address State Name Contact Person Contact Person Contact Person Email ID Operator Type Name Mobile No

List of Exporters of Organic Products under NPOP Sl. No. Exporter Name Address State Name Contact Person Contact Person Contact Person Email ID Operator Type Name Mobile No 1 OLAM AGRO D.NO:484,Appanap Andhra Pradesh Narayana 9642233778 [email protected] PROCESSOR INDIA PVT alem renganath LIMITED village,Amalapuram ,Vemulapudi Post, Narasipatnam Mandal 2 Nava Quality 2‐69A, FATHIMA Andhra Pradesh Mr. ABDUL ALI 8978048158 [email protected] PROCESSOR Foods Private NAGAR, Limited BHAKARAPET A VILLAGE, CHINNAGOTTIGALL U MANDAL CHITTOOR 3 ITC LIMITED ‐ Post Box No 317, Andhra Pradesh Rahul Roy R 8903217935 [email protected] TRADER AGRI BUSINESS Grand Trunk road DIVISION 4 EVERTON TEA 270, Alstonia Drive Andhra Pradesh Mr. ROSHAN 9963475237 [email protected] PROCESSOR INDIA PRIVATE GUNAWARDHANA LIMITED 5 Capricorn Food Palaguntha Village Andhra Pradesh Mr. S.Penchala 9963863754 [email protected] PROCESSOR Products India Ltd ,Sathyavedu Kumar Mandal 6 RMM Food No: 25‐458, Andhra Pradesh Mr. Tanveer 9845319190 [email protected] PROCESSOR Products Gangasagaram Hussain Village, Reddigunta Post, Vellore Road 7 MUDAR INDIA Shed No. 8, Andhra Pradesh Mr. Sudheer Mudar 9393710640 [email protected] TRADER EXPORTS Visakhapatnam Special Economic Zone 1 Sl. No. Exporter Name Address State Name Contact Person Contact Person Contact Person Email ID Operator Type Name Mobile No 8 SAMTFMACS‐ CHINALABUDU, Andhra Pradesh Satish Karothu 9440807445 [email protected] PROCESSOR CENTRAL THURAIGUDA, PROCESSING ARAKU VALLEY UNIT MANDAL, 9 CCL PRODUCTS DUGGIRALA (POST Andhra Pradesh K Nageswara Rao 9490163923 [email protected] , PROCESSOR (INDIA) LIMITED & MANDAL) [email protected] 10 ITC LIMITED‐AGRI P.O.BOX NO. -

A Checklist of Mammals with Historical Records from Darjeeling-Sikkim Himalaya Landscape, India

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication A checklist of mammals with historical records from Darjeeling-Sikkim Himalaya landscape, India Thangsuanlian Naulak & Sunita Pradhan 26 August 2020 | Vol. 12 | No. 11 | Pages: 16434–16459 DOI: 10.11609/jot.6062.12.11.16434-16459 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, the host, and the