Dissertation Submitted to the Sikkim University in Partial Fulfillment of the Award of the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A ABN Sil College 27 Azamabad Tea Estate 98 Absentee of Rajbangsi

Index A ABN Sil College 27 Azamabad Tea Estate 98 Absentee of Rajbangsi Entrepreneurship 112 – 114 B A.C. Sen 130,141 Badal Bhattacharya 181 A.C. Teachers Training College 155 Bagdogra Tea Estate 230 Actor Chabi Biswas 206 Baikanthapur Tea Co. Ltd. 26 Agragami, Jalpaiguri 161 Balak Sangit Group, Jalpaiguri 169 Alipurduar College 162 Bandhab Natya Samaj, Jalpaiguri 150 Alipurduar Tea Co. Ltd. 84 B.C. Ghosh 63, 135, 147, 160, 167 Alipurduar New Town High School 162 Benimadhab Mitra 20, 96 Aluabari Tea Estate 18 Begam Ramimennesha 163 Alimabad Tea Estate 64 Beharilal Ganguly 29, 46 Altadanga Tea Estate 58 Bengal Dooars National Tea Co. Ltd. 31, 67, 68 Amitava Pal Chaudhury 182 Bengal Dooars Bank Ltd. 175 Amiya Banerjee 49, 199 Bengali Association of Darjeeling 185 Amiya Pal Chaudhury 182 Bengali festival in Hill Durga Puja 185 AnandaChandraCollege155 Bengali Tea Garden Babus 30, 31 Anandapur Tea estate 28, 65 Begam Fayzannecha 156 Ananda Chandra Rahut 65, 154 Bhabakinkar Banerjee 79 Annada Charan Sen 24, 68 Bhabanipur Tea Co. Ltd. 76 Andrew Yule & Co. 109 Bhagwan Chandra Bose 58 Anjuman Tea Co. Ltd. 27, 61, 129 Bhojnarayan Tea Estate 28, 35, 99 Arya Natya Samaj, Jalpaiguri 132, 148 – 50, Bipro Das Pal Chaudhury 50, 183, 184 Ashapur Tea Co. Ltd. 77, 100 Bijaynagar Tea Co. Ltd. 104 Ashok Prasad Ray 76, 174 Bijay Basanta Bose 138 Atiabari Tea Co. Ltd. 63, 134 Binay Kumar Dutta 103 302 Biraj Kumar Banerjee 64, 80, 133, 207 Debijhora T.E. 109 BLF System 250 Dharanipur T.E. 90 Brahmaputra Tea Co. -

The Land in Gorkhaland on the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India

The Land in Gorkhaland On the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India SARAH BESKY Department of Anthropology and Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, USA Abstract Darjeeling, a district in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal, is a former colonial “hill station.” It is world famous both as a destination for mountain tour- ists and as the source of some of the world’s most expensive and sought-after tea. For deca- des, Darjeeling’s majority population of Indian-Nepalis, or Gorkhas, have struggled for sub- national autonomy over the district and for the establishment of a separate Indian state of “Gorkhaland” there. In this article, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork conducted amid the Gorkhaland agitation in Darjeeling’s tea plantations and bustling tourist town. In many ways, Darjeeling is what Val Plumwood calls a “shadow place.” Shadow places are sites of extraction, invisible to centers of political and economic power yet essential to the global cir- culation of capital. The existence of shadow places troubles the notion that belonging can be “singularized” to a particular location or landscape. Building on this idea, I examine the encounters of Gorkha tea plantation workers, students, and city dwellers with landslides, a crumbling colonial infrastructure, and urban wildlife. While many analyses of subnational movements in India characterize them as struggles for land, I argue that in sites of colonial and capitalist extraction like hill stations, these struggles with land are equally important. In Darjeeling, senses of place and belonging are “edge effects”:theunstable,emergentresults of encounters between materials, species, and economies. -

Village & Town Directory ,Darjiling , Part XIII-A, Series-23, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERmS 23 'WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIll-A VILLAGE & TO"WN DIRECTORY DARJILING DISTRICT S.N. GHOSH o-f the Indian Administrative Service._ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL · Price: (Inland) Rs. 15.00 Paise: (Foreign) £ 1.75 or 5 $ 40 Cents. PuBLISHED BY THB CONTROLLER. GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY MILl ART PRESS, 36. IMDAD ALI LANE, CALCUTTA-700 016 1988 CONTENTS Page Foreword V Preface vn Acknowledgement IX Important Statistics Xl Analytical Note 1-27 (i) Census ,Concepts: Rural and urban areas, Census House/Household, Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal Workers, N on-Workers (ii) Brief history of the District Census Handbook (iii) Scope of Village Directory and Town Directory (iv) Brief history of the District (v) Physical Aspects (vi) Major Characteristics (vii) Place of Religious, Historical or Archaeological importance in the villages and place of Tourist interest (viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory data. SECTION I-VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1. Sukhiapokri Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 31 (b) Village Directory Statement 32 2. Pulbazar Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 37 (b) Village Directory Statement 38 3. Darjiling Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 43 (b) Village Directory Statement 44 4. Rangli Rangliot Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 49- (b) Village Directory Statement 50. 5. Jore Bungalow Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 57 (b), Village Directory Statement 58. 6. Kalimpong Poliee Station (a) Alphabetical list of viI1ages 62 (b)' Village Directory Statement 64 7. Garubatban Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 77 (b) Village Directory Statement 78 [ IV ] Page 8. -

Mesmerizing Darjeeling Hills Package Starts From* 18,799

Mesmerizing Darjeeling Hills Package starts from* 18,799 4 Nights / 5 Days - Monsoon Dear customer, Greetings from ThomasCook.in!! Thank you for giving us the opportunity to let us plan and arrange your forthcoming holiday. Since more than 120 years, it has been our constant endeavour to delight our clients with the packages which are designed to best suit their needs. We, at Thomascook, are constantly striving to serve the best experience from all around the world. It’s our vision to not just serve you a holiday but serve you an experience of lifetime. We hope you enjoy this holiday specially crafted for your vacation. Tour Inclusions Meals included as per itinerary Sightseeing and Transfers as per itinerary Places Covered 2 Nights 2 Nights Kalimpong Darjeeling www.thomascook.in Daywise Itinerary Arrival NJP Station / Bagdogra Airport - Kalimppong (75 Kms / 03 Hrs): On arrival at NJP Railway Station / (IXB) Bagdogra Airport, (500Ft / 150Mts) will be met by our office Executive who will assist you to board Day 1 your vehicle to Kalimpong (4091 Ft / 1247mts), Check in and over night at Hotel. Kalimpong (43 km / 02 hours) : After breakfast, in the morning, start for Today after Breakfast visit Dello hills, Dr. Graham's Home, Flower Nurseries, Jang-Dong-Palriffo Day 2 Brang and Durbin Dara Hills. Overnight stay in Hotel at Kalimpong. www.thomascook.in Kalimpong - Darjeeling (70 Kms / 03 Hrs): Today after Breakfast visit Transfer to Darjeeling (7380 Ft / 2250 Mts). Overnight stay at Hotel in Darjeeling. Day 3 Darjeeling: Day 4 Early morning tour to Tiger Hills (8364 Ft / 2550 Mts at around 4 AM) to view sunrise over Kanchendzonga Peak (subject to clear weather). -

Paper Code: Dttm C205 Tourism in West Bengal Semester

HAND OUT FOR UGC NSQF SPONSORED ONE YEAR DILPOMA IN TRAVEL & TORUISM MANAGEMENT PAPER CODE: DTTM C205 TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL SEMESTER: SECOND PREPARED BY MD ABU BARKAT ALI UNIT-I: 1.TOURISM IN WEST BENGAL: AN OVERVIEW Evolution of Tourism Department The Department of Tourism was set up in 1959. The attention to the development of tourist facilities was given from the 3 Plan Period onwards, Early in 1950 the executive part of tourism organization came into being with the appointment of a Tourist Development Officer. He was assisted by some of the existing staff of Home (Transport) Department. In 1960-61 the Assistant Secretary of the Home (Transport) Department was made Director of Tourism ex-officio and a few posts of assistants were created. Subsequently, the Secretary of Home (Transport) Department became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Two Regional Tourist Offices - one for the five North Bengal districts i.e., Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, West Dinajpur and Maida with headquarters at Darjeeling and the other for the remaining districts of the State with headquarters at Kolkata were also set up. The Regional Office at KolKata started functioning on 2nd September, 1961. The Regional Office in Darjeeling was started on 1st May, 1962 by taking over the existing Tourist Bureau of the Govt. of India at Darjeeling. The tourism wing of the Home (Transport) Department was transferred to the Development Department on 1st September, 1962. Development. Commissioner then became the ex-officio Director of Tourism. Subsequently, in view of the increasing activities of tourism organization it was transformed into a full-fledged Tourism Department, though the Secretary of the Forest Department functioned as the Secretary, Tourism Department. -

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway

ISSUE ONE Darjeeling Himalayan Railway - a brief description Locomotive availability News from the line Chunbhati loop 1943 Birth of the Darjeeling Railway Agony Point, sometime around the 1930's Chunbhati loop - an early view Above the clouds Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Society ISSUE TWO News from the line Darjeeling, past and present Darjeeling station Streamliner Himalayan Mysteries The Causeway Incident Tour to the DHR A Way Forward ISSUE THREE News from the line To Darjeeling - February 98 Locomotive numbers Timetable Vacuum Brakes To Darjeeling in 1966 Darjeeling or Bust Covered Wagons ISSUE FOUR Report: Visit to India in September 1998 Going Loopy (part 1) Loop No1 Loop No2 Chunbhati loop Streamliner (part 2) Jervis Bay Darjeeling's history To School in Darjeeling ISSUE FIVE News from the line Going Loopy (part 2) Batasia loop Gradient profile Riyang station Zigzag No1 In Search of the Darjeeling Tanks Gillanders Arbuthnot & Co Tank Wagon ISSUE SIX News from the line Repairing the breach Going Loopy (part 3) Loop No2 Zigzag No1 to No 6 Tour - the DHRS Measuring a railway curve David Barrie Bullhead rail ISSUE SEVEN News from the line First impressions Bogies Bogie drawing New Jalpaiguri Locomotive and carriage sheds New Jalpaiguri Depot Going Loopy (part 4) Witch of Ghoom Colliery Engines Buffing gear ISSUE EIGHT May 2000 celebrations News from the line Best Kept Station Competition Impressions of Darjeeling - Mary Stickland Tindharia (part1) Tindharia Works Garratt at Chunbhati Going Loopy – Postscript In And Around Darjeeling -

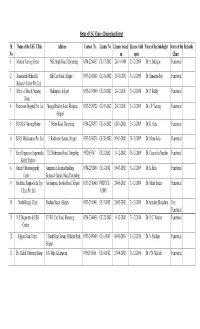

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl. Name of the USG Clinic Address Contact No. License No. License issued License valid Name of the Sonologist Status of the Remarks No. on upto Clinic 1. Mariam Nursing Home N.B. Singh Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254637 CE-17-2002 24-11-1986 31-12-2009 Dr. S. Siddique Functional 2. Anandalok Medical & Hill Cart Road, Siliguri 0353-2510010 CE-18-2002 29-03-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. Shusanta Roy Functional Research Centre Pvt. Ltd. 3. Mitra`s Clinic & Nursing Hakimpara, Siliguri 0353-2431999 CE-23-2002 24-12-2001 31-12-2008 Dr. P. Reddy Functional Home 4. Paramount Hospital Pvt. Ltd. Mangal Panday Road, Khalpara, 0353-2530320 CE-19-2002 28-12-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. J.P. Tayung Functional Siliguri 5. D.D.M.A. Nursing Home 7, Nehru Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254337 CE-16-2002 02-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K. Saha Functional 6. B.B.S. Mediscanner Pvt. Ltd 3, Rashbehari Sarani, Siliguri 0353-2434230 CE-20-2002 09-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mintu Saha Functional 7. Sono Diagnostic Sagarmatha 7/2/2 Robertson Road, Darjeeling 9832063347 CE-2-2002 13-12-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Chayanika Nandan Functional Health Enclave 8. Omkar Ultrasonography Anjuman-E-Islamia Building, 0354-2252490 CE-3-2002 05-03-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K Saha Functional Centre Botanical Garden Road, Darjeeling 9. Suraksha Diagnostic & Eye Ashrampara, Sevoke Road, Siliguri 0353-2530640 PNDT/CE- 28-05-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mukti Sarkar Functional Clinic Pvt. -

North Circle - I

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department Establishment Branch Khadya Bhawan 11A,Mirza Ghalib Street,Kolkata -87. No.: 52-E/PWD-11041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) Dated:17.08.2020 NOTIFICATION The Restructuring of various offices under the preview of the Public Works Department has been undertakenvide Notification No.178 dated 20.12.2019. As a result thereof, necessity of re-jurisdiction of Divisions and Sub-Divisions under the Zones of PWD have been felt to cope with the requirement of proper implementation and execution of works relating to restructuring of various offices under Public Works Department. 2. Now, in view of above, the Governor is pleased, in the interest of public service to create re-jurisdiction of Divisionsand Sub-Divisionsunder the Zonesof PWDin the following manner: (AI Rejurisdiction of Divisionand Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief Jurishdlction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) NORTH CIRCLE - I Coochbehar Division Coochbehar Division-I Coochbehar Sub-Division-I Cooch Behar Sub-Division Eastern part of Dharala river of Cooch Behar-I block inclusive of Cooch Behar Municipality Coochbehar Sub-Dlvlsion-ll Tufanganj Sub-Division Tufanganj-I inclusive of Tufanganj municipality and Tufanganj-II block Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata-I inclusive of Dinhata erstwhile Jorai Costr. Sub- municipality and Dinhata-II block and Division. Sitai block Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Sub-Division. Alipurduar Sub-Division Block Alipurduar-I inclusive of Alipurduar Municipality and Eastern part of Kalchini Block consisting of Buxa and Jayanti Notification No: 52-E/PWD-ll041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) dated 17.08.2020 Rejurisdiction of Division and Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief lurishdiction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) Kamakhyaguri Constr. -

Urban History of Darjeeling Through Phases : a Study of Society, Economy and Polity "The Queen of the Himalayas"

URBAN HISTORY OF DARJEELING THROUGH PHASES : A STUDY OF SOCIETY, ECONOMY AND POLITY OF "THE QUEEN OF THE HIMALAYAS" THESIS SUBMITTED BY SMT. NUPUR DAS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS) OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2007 RESEARCH SUPERVISOR Dr. Dilip Kumar Sarkar Controller of Examinations University of North Bengal CO-SUPERVISOR Professor Pradip Kumar Sengupta Department of Political Science University of North Bengal J<*eP 35^. \A 7)213 UL l.^i87(J7 0 \ OCT 2001 CONTENTS Page No. Preface (i)- (ii) PROLOGUE 01 - 25 Chapter- I : PRE-COLONIAL DARJEELING ... 26 - 48 Chapter- II : COLONIAL URBAN DARJEELING ... 49-106 Chapter-III : POST COLONIAL URBAN SOCIAL DARJEELING ... 107-138 Chapter - IV : POST-COLONIAL URBAN ECONOMIC DARJEELING ... 139-170 Chapter - V : POST-COLONIAL URBAN POLITICAL DARJEELING ... 171-199 Chapter - VI : EPILOGUE 200-218 BIBLIOGRAPHY ,. 219-250 APPENDICES : 251-301 (APPENDIX I to XII) PHOTOGRAPHS PREFACE My interest in the study of political history of Urban Darjeeling developed about two decades ago when I used to accompany my father during his official visits to the different corners of the hills of Darjeeling. Indeed, I have learnt from him my first lesson of history, society, economy, politics and administration of the hill town Darjeeling. My rearing in Darjeeling hills (from Kindergarten to College days) helped me to understand the issues with a difference. My parents provided the every possible congenial space to learn and understand the history of Darjeeling and history of the people of Darjeeling. Soon after my post- graduation from this University, located in the foot-hills of the Darjeeling Himalayas, I was encouraged to take up a study on Darjeeling by my teachers. -

Imaging the Landscape Experience of Darjeeling

NEPAL BHUTAN SIKKIM BHUTAN KALIMPONG II DARJEELING PULBAZAR RANGLI GORUBATHAN RANGLIOT KALIMPONG BIHAR JOREBUNGALOW SUKIAPOKHRI BANGLADESH KURSEONG LOCATION MIRIK NEPAL e history of development of hill stations in India during colonial period dates back to the nineteenth century, when due to establishment of Railways, JHARKHAND MATIGARA NAXALBARI JALPAIGURI British sought to inhabit these cooler areas in the harsh summer. Situated in the Eastern Himalayan belt, a similar hill station, Darjeeling gained popularity PHANSIDEWA KHARIBARI both in India and abroad as a tourist destination. is was facilitated by the commencement of Darjeeling Himalayan Railway between Siliguri, in the plains of Bengal to the hills of Darjeeling. Although intended to support the thriving Tea industry, the DHR soon became one of the most celebrated and BANGLADESH BIHAR ORISSA NEPAL acclaimed train journeys in the world. e toy train chugs along the hill side oering a variety of landscape experiences taking the passenger from the heat of the plains to the bracing mountain air. 3 0 0 ! 12 Darjeeling 00 0 SIGNIFICANT ISSUE 150 But in the post-independent scenario, it witnessed many challenges. With change in ownership, faster and ecient modes of transport and the recurring landslides, the toy train became less preferred and insolvent. Ghum 0 20 Manibhanjan Ridge Senchal 1 2100 6 e land-use changes altered the landscape experience that the DHR once boasted. With lesser travellers and obsolete engineering structure, the railway 00 2400 6 seems to have lost its value, and association with the community. e places and landmarks that narrated the glorious past of the railway were soon forgot- Tiger Hill 0 00 0 ten, and the need to conserve the heritage was realised. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

Darjeeling Railway

History and Description Darjeeling Railway (India) History The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway is intimately linked with No 944 the development of Darjeeling as the queen of hill stations and one of the main tea-growing areas in India, in the early 19th century. The densely wooded mountain spur on which Darjeeling now stands was formerly part of the Kingdom of Sikkim. It was adopted by the British East India Company as a rest and Identification recovery station for its soldiers in 1835, when the area was leased from Sikkim and building of the hill station began, Nomination The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway linked to the plains by road. The region was annexed by the British Indian Empire in 1858. Location Darjeeling District, State of West Calcutta had been linked by rail in 1878 to Siliguri, in the Bengal foothills of the Himalaya. By this time the tea industry had become of great importance for the Darjeeling region, and State Party Republic of India the existing road transport system was inadequate to cope with the increased traffic. Franklin Prestage, Agent of the Date 3 July 1998 Eastern Bengal Railway, submitted a detailed proposal for a steam railway from Siliguri to Darjeeling. This received official approval and construction work began immediately. By 1881 it had been completed in three stages. The privately owned Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Justification by State Party (hereafter referred to as the DHR) was purchased by the The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway is a unique example of Government of India in October 1948. Since 1958 it has construction genius employed by railway engineers in the been managed by the State-owned Northeast Frontier latter part of the 19th century.