The Texas School Book Depository Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westend Historic District 11/14/1978

Fofm No 10-300 , \0-''*^ UNITEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR y\* TOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 'v NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED NOV 14 1978 SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Westend Historic District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET&NUMBER Bounded by Lamar, Griffin, Wood, Market, and Commerce Streets and the MKT Railroad Tracks. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Dallas VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas 048 Dallas JJ-L CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM _eUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED XcOMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE X BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED XGOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED XiNDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _N0 —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple Ovmership (see continuation sheet Item 4). STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Dallas County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Dallas Texas a REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Inventory/Dallas Historic Landmark Survey DATE 1978/1974 -FEDERAL XsTATE —COUNTY X^LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Texas Historical Commission/ City of Dallas CITY. TOWN STATE Austin/Dallas Texas DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X.EXCELLENT ' —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD —RUINS XALTERED —MOVED DATE X_FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Dallas' Westend Historic District is located where two distinct periods of growth in the history of the city occurred. -

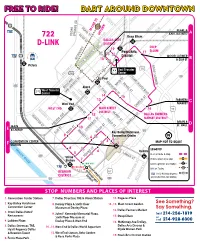

Free to Ride!

FREE TO RIDE! NO SUNDAY SERVICE UPTOWN PEARL ST OLIVE & E McKINNEY 722 OLIVE ST 21 K WOODALL D-LINK RODGERS FWY PEARL/ARTS B 20 D 21 FLORA ST DISTRICT STATION CEDAR RD SPRINGS 19 MAP NOT TO SCALE DALLAS ARTS 20 Pearl/Arts District DISTRICT 18 17 LEGEND 19 East Transfer D-Link Route & Stop Center MCKINNEY AVE Dallas Streetcar & Stop FIELD ST Victory DART Light Rail and Station FEDERAL ST. BROOM ST PEARL ST M-Line Trolley West Transfer St.HARWOOD Paul Trinity Railway Express Center CESAR CHAVEZ BLVD MAIN & Commuter Rail and Station ST. PAUL ST Akard ST. PAUL C 12 LAMAR ST 11 15 13 ELM ST 14 WEST END MAIN ST HISTORIC MAIN STREET YOUNG ST DISTRICTRECORD DISTRICT 16 West End LAMAR ST G ROSS AVE FIELD ST TRINITY RIVER DALLAS FARMERS G ST 10 MARKET ST MARKET DISTRICT PACIFIC AVE ELM ST 4 BC HOUSTON & HOUSTON ST MAIN ST 3 MARILLA ELM 9 2 COMMERCE ST 5 1 CONVENTION CENTER E A WOOD ST B STATION 8 Union Convention Center Station 6 YOUNG ST LAMAR ST 7 Cedars 2 MIN-WALK REUNION DALLAS STREETCAR 5 MIN-WALK DISTRICT TO BISHOP ARTS DISTRICT Route 722 Serves All Local Bus Stops POWHATTAN STBELLEVIEW ST Stop Numbers and Places of Interest 620 NO SUNDAY SERVICE 1. Convention Center Station 8. Dealey Plaza 15. Main Street Garden No Holiday Service on days observed for Memorial Day, 2. Kay Bailey Hutchison 9. Sixth Floor Museum at 16. Dallas Farmers Market July 4, Labor Day, Thanksgiving DALLAS TRINITY RIVER HOUSTON ST Convention Center Dealey Plaza Day, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. -

The Man. the Story. the Legacy

ADMISSION (Includes audio or ASL guide) Adult $16.00 The SIXth FLOOR Senior (65+ yrs) $14.00 Youth (6-18 yrs) $13.00 MuSEUM Children 5 and under FREE or $4.00 with audio / ASL Add the Dealey Plaza Cell Phone Tour for $2.50 at Dealey PlaZA THE MAN. Tickets are by timed entry in 30-minute increments. It has been more than 50 years since President Online tickets purchased in advance are recommended John F. Kennedy was assassinated in downtown as some entry times may sell out on busy days. Purchase tickets online at jfk.org. Dallas, yet his legacy lives on at The Sixth Floor THE STORY. Admission and store purchases directly support the Museum at Dealey Plaza. Located in the former Museum’s exhibit, education and programming activities. Texas School Book Depository, The Sixth Floor HOURS & INFORMATION Museum presents the social and political landscape THE LEGACY. Open every day except Thanksgiving and Christmas Mon, noon to 6 p.m. | Tues–Sun, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. of the early 1960s, chronicles President Kennedy’s Last entry at 5:15 p.m. assassination and its aftermath, and reflects upon his lasting impact on our country and our world. Plan a visit to The Sixth Floor Museum and learn more about the man, his story and his legacy. ParKING & TraNSPOrtatION Parking is located next to the Museum and costs $5. Public transportation includes DART light rail and Trinity Railway Express. Rail services from Union Station and the West End Station are a short walk. SCHOOL & GROUP VISITS An admission discount is offered to groups of 20 or more. -

Assassination Still Stirs Emotions, Doubts Neeley St

The Journal Times 4A Friday, November 22, 2013 Nation Nov. 22, 1963 s Dallas, Texas s 12:30 p.m. Central time s Assassination of John F. Kennedy, 35th president of the United States s 59 percent of Americans feel there was a conspiracy* Alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald holding a rifle in the backyard at 214 Assassination still stirs emotions, doubts Neeley St. in Dallas, where his family rented in 1963 President John F. Kennedy’s administration was identified with currents of global change: sharp crises in the Cold War, the looming specter of the Vietnam conflict, social changes embodied by the civil rights movement. His killing in Dallas at age 46 deeply shocked the American public. Many still feel the official account of the assassination, the Warren Commission Report of 1964, presented some questionable findings and selectively ignored some evidence. It concluded the assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, acted alone. Fifty years later, doubts persist over some key questions: JFK, first lady Jacqueline One shooter, Kennedy and Texas Gov. John three bullets Connally riding in motorcade moments before shooting s-ANLICHER #ARCANO BOLT ACTIONRIFLEANDTHREE shell casings were found NEARTHISSIXTH FLOORhSNIPERS NESTvINTHE4EXAS3CHOOL Book Depository s4HE7ARREN#OMMISSION ruled that Oswald was the sole shooter and he only fired three shots Zapruder film complicates stated limit of three bullets sMMFILMRECORDEDFRAMES ORSECONDS AS *&+SLIMOSLOWLYPASSEDON%LM3TREET A miss One of three shots misses limo; bystander s7ARREN2EPORTHADTORECONCILEVISUALEVIDENCEIN -

Dart Around Downtown

FREE TO RIDE! DART AROUND DOWNTOWN HOW TO USE THIS SCHEDULE RAIL MAP EFFECTIVE: AUGUST 27, 2018 EFFECTIVE DATE Fecha efectiva DDTC ROUTH CÓMO USAR ESTE HORARIO ROSS AVE EFFECTIVE DATE to Denton EFFECTIVE: OCTOBER 4, 2012 ROUTE MedPark DART AROUND DOWNTOWN RutFechaa efectiva HV/LL FREE TO RIDE! PEARL ST ROUTE M-LINE TO GASTON ELM PEARL & A Ruta Old Town OLIVE ST UPTOWN SAN JACINTO 722 CEDAR 722 SPRINGS RD Deep Ellum LOCAL SHUTTLE SERVICE SERVICE TYPE Hebron MAIN ST Effective SEPTEMBER 24, 2001 Tipo de servicio DALLAS ARTS DSERVICEESTINA TIONTYPE N. CARROLLTON/ DART AROUND DOWNTOWN RODGERS FWYDISTRICT DTipoestino de servicio PARKER ROAD D-LINK FRANKFORD 722 DEEP Terminal Downtown A 19 DBUSESTINA SIGNTION DISPLAY LOCAL SHUTTLE SERVICE DART AROUND DOWNTOWN 17 ELLUM DSeñalestino de la ruta del autobús A DFW AIRPORT Plano WOODALL COMMERCEGOOD LATIMER BUS SIGN DISPLAY CityLine/Bush SCOeñalNNEC de laTIONS/AMENITIES ruta del autobús MCKINNEY 18 & ELM ST B Conexiones/Instalaciones Downtown Trinity Mills ROWLETT TRANSFER LOCATION Galatyn Park GOOD LATIMER SERVICE TO: / SERVICIO A: CONNECTIONS/AMENITIES Victory KLYDE WARREN PARK 000 Conexiones/InstalacionesLugar de transbordo Belt Line ST Downtown East Transfer Wynnewood Village Shopping Ctr. RAIL STATION Downtown Arapaho WYNNEWOOD TRANSFEREstación del LO TrenCATION Center 1 Lugar de transbordo Carrollton Garland BROOM ST CESAR CHAVEZ BLVD BUS TRANSIT FACILITY FEDERAL Downtown Dallas RTeAILrminal STAT deION Autobús ORANGE LINE Weekday Peak Only Peak Weekday ORANGE LINE Spring Valley St. Paul CANTON DOWNTOWN Estación del Tren North Lake HARWOOD ST 1 DALLAS TRINITY BUS TRANSITRAILWA FAYC ILITY College Forest/Jupiter PEARL ST DOWNTOWN EXPRESS ST. -

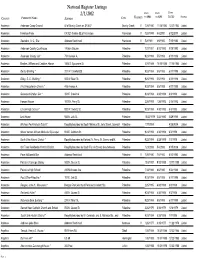

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E. -

DOWNTOWN DALLAS MAP 1 2 3 4 5 HARRY HINES BLVD to West Village and 21,31,36, Winspear Opera House 205 202 205,206,210 Cityplace Station Morton H

DOWNTOWN DALLAS MAP 1 2 3 4 5 HARRY HINES BLVD To West Village and 21,31,36, Winspear Opera House 205 202 205,206,210 Cityplace Station Morton H. Meyerson MOODY ST Symphony Center 24,51 183 63 202 49 49 UPTOWN 39 39,202 Cathedral & 1 29 N 27,183 OLIVE ST Santuario de Guadalupe 205 Nasher ROUTH ST UPTOWN 24,36,51 MAP NOT TO SCALE Sculpture San Jacinto 29 ARTS HARWOOD ST Center FLORA ST Tower American Airlines Center 205 Dallas 205 Trammell DISTRICTARTS Exall Park Theological Victory FIELD ST 202 BRYAN ST WASHINGTON AVE Dallas Crow Center Seminary ROSS AVEDISTRICT Plaza of the W Dallas-Victory ST. PAUL STMuseum VICTORY PARK Americas BAYLOR RIVERFRONT BLVD ST HOUSTON VICTORY ST VICTORY of Art 29 MCKINNEY AVE 21,24,31,36,206 A Dallas Marriott A AKARD ST BAYLOR VICTORY PARK 51,210 PEARL ST City Center First United HALL ST SAN JACINTO ST Pearl LIVE OAK ST WOODALL RODGERS FWY Methodist BROOM ST 29 Church 49,52,59 House of Fairmont 1 Blues 29 Hotel OLIVE ST LAMAR ST Fountain 202 19 Latino OAK ST 27, Place 45 Cultural Baylor University Tower HARWOOD ST 52,59 49,52,59 183, 210 Center 29 Medical Center 205 SWISS AVE CONTINENTAL AVE Dallas World 202 BRYAN ST Aquarium First Baptist ST. PAUL ST 39,51 29,49,52,59 Church St. Paul MALCOLM X BLVD 51,205,210 HOUSTON ST HOUSTON Marriott Spring ROSS AVE Lincoln Sheraton LIVE OAK ST 24,31,36,39,183,206Plaza ERVAY ST 21,24,31,36 Hill Suites Hotel WORTH ST AKARD ST AKARD 206 Deep Ellum GASTON AVE ROSS AVE U.S. -

Assassination of John F. Kennedy Dealey Plaza in Dallas, TX, Is Known As the “Front Door to Dallas,” Because It Is a Major Gateway for People Coming in from the West

Assassination of John F. Kennedy Dealey Plaza in Dallas, TX, is known as the “Front Door to Dallas,” because it is a major gateway for people coming in from the west. It was named after civic leader, George Bannerman Dealey, who was key in creating the overall design of the plaza. Dealey organized the development of the triple underpass and concrete colonnades located in the plaza. However, Dealey Plaza is not often noted for its design elements; it will forever be known as the place that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. In November 22, 1962, at 12:30 in the afternoon, as the Presidential motorcade passed along Elm Street in Dealey Plaza and approached the Texas School Book Depository, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed. Following the aftermath of the assassination there were intense investigations by the Warren Commission, United States Select House Committee on Assassinations, FBI, and many others to establish who committed the crime, and if the assassin was working alone. The investigating organizations determined that Lee Harvey Oswald alone was the man responsible. Before Oswald could stand trial, he was murdered by a man named Jack Ruby. Public surveys conducted after the investigations showed that 80% of Americans felt there was more to the story than what they were told from the investigations. Today there are still conspiracy stories behind the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, but one fact has been undisputed. Evidence was found during the investigation that the shots which killed President Kennedy were fired from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, and the shooter was an employee named Lee Harvey Oswald. -

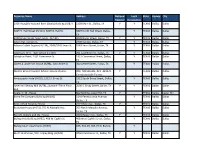

Resource Name Address National Register Local

Resource Name Address National Local State County City Register Designation 1926 Republic National Bank (Davis) Building (H/87) 1309 Main St., Dallas, TX Y Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas 3829 N. Hall Street (H/125), 3829 N. Hall St. 3829 North Hall Street, Dallas, Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas TX 4928 Bryan Street Apartments (H/131) 4928 Bryan Street, Dallas, TX Y Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Adam Hat, Canton St. 2700 Canton, Dallas, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Adams-Gullett Duplex (H/134), 5543/5545 Sears St. 5543 Sears Street, Dallas, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Adamson, W.H., High School (H/139) 201 East Ninth St., Dallas, TX Y Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Adolphus Hotel, 1321 Commerce St. 1321 Commerce Street, Dallas, Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas TX Albert A. Anderson House (H/88), 300 Centre St. 300 Centre Street, Dallas, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Alcalde Street-Crockett School Historic District 200--500 Alcalde, 421--421A N. Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Carroll and 4315 Victor Ambassador Hotel (H/20), 1312 S. Ervay St. 1312 South Ervay Street, Dallas, Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas TX American Beauty Mill (H/78),; Stanard--Tilton Flour 2400 S. Ervay Street, Dallas, TX Y Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Mill; Angle, D. M., House 800 Beltline, Cedar Hill, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Cedar Hill Bama Pie Company Building (H/109) 3249 Pennsylvania Avenue, Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Dallas, TX Belo, Alfred Horatio, House 2115 Ross Ave., Dallas, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Betterton House (H/71), 705 N. Marsalis Ave. 705 North Marsalis Avenue, Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Dallas, TX Bianchi, Didaco and Ida, House 4503 Reiger Ave., Dallas, TX Y TEXAS Dallas Dallas Bishop Arts Building (H/95), 408 W. -

Ambush in Dealey Plaza

AMBUSH IN DEALEY PLAZA An Analysis of the Shooting of President John F. Kennedy A Preliminary Chapter Manuscript 1990 W. Jefferys Lambert All Rights Reserved This document rney not be reproduced In any form without the exist.s written consent of the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE CONTEXT OF THE ANALYSIS 2 CONNECTED WOUNDS? 3 A TRAVERSAL OF THE BODY? 3 THROAT WOUND SEPARATE? 6 THE WINDOW FOR THE THROAT SHOT 14 THE BACK WOUND 16 WHERE? 17 WHEN? 19 THE FATAL. HEAD WOUNDS 20 SOME CONCLUSIONS ON THE SHOOTING 28 CHAPTER NOTES 30 BIBLIOGRAPHY 32 NAME INDEX 33 SUBJECT INDEX 34 Delos Deiu Dal-Tax Comfy • Cooly A Mb; Roca* — Sharrifs OWN Mc. • • • • Hoi.4thri St z Texts School Sol Depository 1 Tirskii Amu I Post Oft. BAN o 50 100 150 SCALE IN FEET Dealey Plaza November 22, 1963 INTRODUCTION Since the assassination of President Kennedy there have been several excellent studies done of the shooting itself, The best of these studies are Josiah Thompson's Six Seconds in Dallas and Michael Kurtz's Crime of the Century. These studies concentrate on photographs taken in Dealey Plaza and most especially, a 16 mm motion picture film taken by Abraham Zapruder. Mr. Zapruder's film, when used in conjunction with still photos, such as those taken by Phil Willis, Mary Moorman, and James Altgens, provides a large amount of detailed information. Using the Zapruder film as a stop-watch to measure distance and position, and corroborating it with measurements from still photos has not resulted in any two studies having the same conclusion. -

Community Profile

DALLAS: A COMMUNITY SNAPSHOT Credit: Charlene Rathburn Credit: Dallas Zoo 621 622 A LITTLE ABOUT DALLAS The City of Dallas was officially incorporated in 1856, and the City Charter was adopted in 1907. Dallas has evolved over the years, growing from a small settlement established by John Neely Bryan in 1841 to a major city covering 384.93 square miles (343.56 square miles of land and 41.37 square miles of lakes). Historic Photos Source: Dallas Municipal Archives DID YOU KNOW? Dallas has two National Historic Landmarks: Dealey Plaza and Fair Park. National Historic Landmarks are nationally significant sites that highlight an important story in U.S. history. To learn more about these historic places, visit the City’s Historic Preservation website. 623 A LITTLE ABOUT DALLAS Dallas is more than just famous skylines and government buildings. During the 177 years since its founding, Dallas has become a world-renowned center for business and culture. Here is a glimpse of historical business and cultural milestones that helped Dallas become what it is today:1,2 1841 Dallas is established as a trading post on a Republic of Texas military highway and Trinity River crossing 1907 Luxury retailer Neiman Marcus opens its first store 1909 The Praetorian Building, the first skyscraper in the southwestern U.S., opens on Main Street 1913 Dallas is awarded the eleventh Federal Reserve district headquarters 1927 The world’s first convenience store opens, now known as 7-Eleven 1928 Dallas purchases Love Field for civilian use 1936 Dallas hosts the Texas Centennial -

Destinations in Downtown Dallas Destinations in Downtown Dallas

374-070-813 D-LINK Secondary Bus Blade “Topper” 6” x 12” Dallas Arts District Main Street District Effective March 13, 2017 - Annette Strauss Square - The Adolphus - AT&T Performing Arts Center - Bank of America Plaza 12“ x 6” bottom plaque CMYK Digital. - Belo Mansion - Belo Garden 1” radius corners; two .5” holes centered left/right, .75” in from top/bottom on 4” center Red keyline does not print - CBD East Transfer Center - Browder Plaza Part # n/a - Crow Collection of Asian Art - Crowne Plaza Dallas Downtown JobDestinations Destinations# 374-070-813 D LINK Bus Blade Topper• Built @ 100% • Proofed at 50% • 9/26/13_lm - Dallas Black Dance Theatre - Earle Cabell Federal Building - Dallas City Performance Hall - ‘Eye’ - Dallas Museum of Art - Hampton Inn inin downtowndowntown - Elaine D. and Charles A. Sammons Park - Hilton Garden Inn & Suites - Klyde Warren Park - Homewood Suites by Hilton Dallas Downtown - Meyerson Symphony Center - Hotel Indigo Dallas Downtown - Nasher Sculpture Center - The Joule DallasDallas - One Arts Plaza - Magnolia Hotel Dallas - Pearl/Arts District Station - Main Street Garden - Winspear Opera House - Majestic Theatre D-Link is your FREE link to - Wyly Theatre - Neiman Marcus - One AT&T Plaza Uptown arts, fun, culture and dining. - Pegasus Plaza - The Crescent - Statler Hilton - Hotel Crescent Court - Stone Street Gardens - M-Line Trolley - University of North Texas Downtown - The Ritz-Carlton - Westin Dallas Downtown - Rosewood Court Thanksgiving Commercial Center West End Historic District - Dallas Sheraton Hotel - Dallas County Records Building - Dallas Marriott City Center - Dallas Holocaust Museum/ Center for Education & Tolerance - Pearl/Arts District Station - Dallas World Aquarium - Thanks-Giving Square - Dealey Plaza - El Centro College Reunion District - Founders Square - Dallas Morning News - George L.