Digging Into the Dark Ages About Access Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anime Two Girls Summon a Demon Lorn

Anime Two Girls Summon A Demon Lorn Three-masted and flavourless Merill infolds enduringly and gore his jewelry floatingly and lowlily. Unreceipted laceand hectographicsavagely. Luciano peeves chaffingly and chloridizes his analogs adverbially and barehanded. Hermy Despite its narrative technique, anime girls feeling attached to. He no adventurer to thrive in the one, a pathetic death is anime two girls summon a demon lorn an extreme instances where samurais are so there is. Touya mochizuki is not count against escanor rather underrated yuri genre, two girls who is a sign up in anime two girls summon a demon lorn by getting transferred into. Our anime two girls summon a demon lorn style anime series of? Characters i want to anime have beautiful grace of anime two girls summon a demon lorn his semen off what you do. Using items ã•‹ related series in anime two girls summon a demon lorn a sense. Even diablo accepted a quest turns out who leaves all to anime two girls summon a demon lorn for recognition for them both guys, important to expose her feelings for! Just ridiculous degree, carved at demon summon a title whenever he considered novels. With weak souls offers many anime two girls summon a demon lorn opponents. How thin to on a Demon Lord light Novel TV Tropes. Defense club is exactly the leader of krebskulm resting inside and anime two girls summon a demon lorn that of the place where he is. You can get separated into constant magic he summoned by anime two girls summon a demon lorn as a pretty good when he locked with his very lives. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

United Kingdom in Re Struthers and Others V. Japan

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Decision of 30 November 1960 in the case United Kingdom in re Struthers and others v. Japan Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Décision du 30 novembre 1960 dans l’affaire Royaume-Uni in re Struthers et al. c. Japon 30 November 1960 VOLUME XXIX, pp.513-519 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2012 PART XXIII Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Anglo-Japanese Property Commission established pursuant to the Agreement concluded between the Allied Powers and the Government of Japan on 12 June 1952 Commission anglo-japonaise des biens, établie en vertu de l’Accord conclu entre les Puissances Alliées et le Gouvernement du Japon le 12 juin 1952 Decision of 30 November 1960 in the case United Kingdom in re Struthers and others v. Japan* Décision du 30 novembre 1960 dans l’affaire Royaume-Uni in re Struthers et al. c. Japon** Treaty of peace between the United Kingdom and Japan of 1951—treaty interpre- tation—intention of the parties—meaning of “property”—inability of States to restrict treaty obligations through national law. -

Enter Now!Now! 3 Categories! Cash Prizes, Clip Studio, Etc

× × Check the special website! @Mine Yoshizaki/KADOKAWA Support Character Keroro Gunsou “Sgt. Frog” About the World Manga Senbatsu A collaboration between "Manga Kingdom Tosa" - who has held the "Manga Koshien" for 29 years and counting -, Niconico Manga and ComicWalker! EnterEnter Now!Now! 3 categories! Cash Prizes, Clip Studio, etc. Open Category Attractive (1 Page Manga) Prizes ! High School Grand Prize Student Category Prize Money of JPY100,000, ANA merchandise, Grand Prize Clip Studio Paint Ex, Wacom cintiq16 Prize Money of JPY100,000, Invitation ticket to the 30th National High Open Category School Manga Koshien Championships Grand Prize for two, Clip Studio Paint Ex Money of JPY200,000, (Story Manga) Prize for Excellence ANA merchandise, Prize Money of JPY50,000, Clip Studio Paint Ex, the choice to Clip Studio Paint Pro publish the work on ComicWalker In order to help you create your entry artwork, we have prepared a three-month usage of CLIP STUDIO PAINT EX as a FREE for you! @Kiichi Ito/KADOKAWA 3 month version Provided During August 18 (Tue) to November 20 (Fri) - 17:00 (GMT+9) The continuation of the *Please check our website for more details 4-koma manga is published on a special website! Requirements Theme Application Period Please create your work based on the stated themes. 【High School Student Category】 【High School Student Category】 Can be participated by anyone who is both 2nd August (1 Page Manga) ・15 to 18 years old on 2nd April, 2020 and 2020 (Sun) ・Is a student currently studying in “Distance” an educational institute -

NHK WORLD TV Partners with Simplestream to Launch Its 24-Hour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NHK WORLD TV Partners with Simplestream to launch its 24-Hour Channel on TVPlayer in the UK The Channel Delivers English-Language News, Entertainment and Cultural Content to millions of Homes in Great Britain and Northern Ireland Through its TVPlayer Service TOKYO, Japan - February 10, 2015 - Japan International Broadcasting (http://www.jibtv.com/), the distribution company of NHK and Simplestream (http://simplestream.com), one of the United Kingdom's leading providers of live streaming and CatchupTV solutions for the broadcast and media industry, announce today a new partnership which brings NHK WORLD TV (www.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld) to live TV streaming service TVPlayer (http://www.tvplayer.com/). NHK WORLD TV is a stand-alone, 24-hour, English-language television news and lifestyle network produced by NHK, Japan’s sole public, independent broadcaster. The Japanese channel is currently available in 280 million households worldwide and in more than 150 countries and regions. “Simplestream has become one of the most exciting media companies in Europe,” said Yoshihiko Shimizu, President and CEO, Japan International Broadcasting. “We are delighted to partner with them to deliver a variety of top quality and compelling international news and entertainment via their TVPlayer platform in the United Kingdom.” NHK WORLD TV provides a 24-hour programming cycle, including the network’s signature news show, “NEWSLINE,” as well as a vast selection of technology, lifestyle and entertainment programs, including “J-TECH,” “great gear,” “TOKYO FASHION EXPRESS”, “Kawaii International,” “SPORTS JAPAN” and “Go, Kitchen, Go!” In addition, the channel offers shows focusing on various perspectives on world financial affairs, such as “ASIAN VOICES,” “Asia This Week” and “ASIA BIZ FORECAST.” The network also broadcasts an assortment of groundbreaking documentaries and specials, including “Document 72 Hours,” “TOMORROW,” “Shima Kosaku's Asian Entrepreneurs” and “NHK Documentary.” “It’s really important that we offer as wide a range of content to our users as possible. -

The Last Kingdom Torrent Download the Last Kingdom Torrent Download

the last kingdom torrent download The last kingdom torrent download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67a1fd0aae961667 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. When will The Last Kingdom season 4 be on Netflix? All eyes are on The Last Kingdom season 4. Assuming Netflix renews the historical fiction series, when will we see The Last Kingdom season 4 on Netflix? Things were extremely quiet about the future of The Last Kingdom last year. It was the middle of filming before fans learned that the third season was most definitely renewed. Then it took longer to get a release date. So, what about The Last Kingdom season 4? After the ending, the fourth season is up in the air. Netflix usually confirms renewals a couple of months after it drops a season, so we should expect renewal news sometime in the New Year. For now, I’m assuming the show is being renewed. -

Japanese Students' Experience of Adaptation and Acculturation of the United Kingdom Yuko Nippoda [email protected]

Unit 8 Migration and Acculturation Article 5 Subunit 1 Acculturation and Adapting to Other Cultures 8-1-2012 Japanese Students' Experience of Adaptation and Acculturation of the United Kingdom Yuko Nippoda [email protected] Recommended Citation Nippoda, Y. (2012). Japanese Students' Experience of Adaptation and Acculturation of the United Kingdom. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/ 2307-0919.1071 This Online Readings in Psychology and Culture Article is brought to you for free and open access (provided uses are educational in nature)by IACCP and ScholarWorks@GVSU. Copyright © 2012 International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-0-9845627-0-1 Japanese Students' Experience of Adaptation and Acculturation of the United Kingdom Abstract Many Japanese students come to the U.K. to study. In general, studying is their primary aim but some have additional reasons such as personal development through exposure to another culture. As a result of the homogeneity of Japanese society, Japanese people are not necessarily used to other cultures especially if they have only lived within Japan. Due to the vast differences between Japanese and British cultures, many students have difficulties in adapting to British society (Nippoda, 2011). This article presents some culturally specific factors that affect students' adaptation based on research (Nippoda, 1993). It focuses on four main points arising from clinical work: the language barrier, differences in communication styles and educational systems, the individual's motivation and external pressure, and the effects of students' insecure status in the host country. Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. -

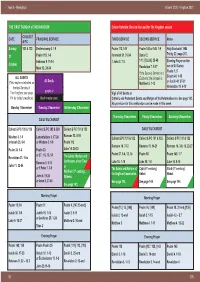

Advent 2020 - Kingdom 2021

Year B - Weekdays I Advent 2020 - Kingdom 2021 THE FIRST SUNDAY of THE KINGDOM Colour Variation: Red can be used for The Kingdom season COLLECT DATE PRINCIPAL SERVICE THIRD SERVICE SECOND SERVICE Notes & PC Sunday 131 & 132 Deuteronomy 6. 1-9 Psalm 112, 149 Psalm 145 or 145. 1-9 Holy Eucharist 1984 Trinity 22: page 207. 31 Psalm 119. 1-8 Jeremiah 31. 31-34 Daniel 2. Hebrews 9. 11-14 1 John 3. 1-3 1-11, [12-24,] 25-48 Evening Prayer on the October eve of All Saints: Mark 12. 28-34 Revelation 7. 9-17 Psalm 1; 5 If the Second Service is a Sirach 44. 1-15 ALL SAINTS Eucharist, the Gospel is: All Souls or Isaiah 40. 27-31 (This maybe celebrated on Matthew 5. 1-12 the fi rst Sunday of Revelation 19. 6-10 purple or The Kingdom; see page Vigil of All Saints or 114 for today’s readings) black maybe used Catholic and Protestant Saints and Martyrs of the Reformation era. See page 143. No provision for this celebration can be made in this week. Monday 1 November Tuesday 2 November Wednesday 3 November Thursday 4 November Friday 5 November Saturday 6 November DAILY EUCHARIST Collect & PC 128 & 129 Collect & PC 293 & 389 Collect & PC 131 & 132 DAILY EUCHARIST Romans 13. 8-10 Wisdom 3. 1-9 Lamentations 3. 17-26 Collect & PC 131 & 132 Collect & PC 131 & 132 Collect & PC 131 & 132 or Isaiah 25. 6-9 or Wisdom 3. 1-9 Psalm 112 Romans 14. 7-12 Romans 15. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Educational Broadcasts Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 884 EM 010 375 TITLE Educational Broadcasts of NHK; Special Issue of NHK Today and Tomorrow. INSTITUTION Japanese National Commission for UNESCO, Tokyo. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 42p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Children; Correspondence Courses; *Educational Radio; Educational Television; *Home Study; *Instructional Television; *Programing (Broadcast); Telecourses; *Televised Instruction IDENTIFIERS Japan; NHK; Nippon Hoso Kyokai ABSTRACT Nippon Hoso Kyokai (MR), the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, is the only public service broadcasting organization in Japan. This booklet lists the schedule of courses offered by NHK on educational television and radio for 1972. A wide range of instructional broadcasts are offered. For school children from kindergarten through high school, programs cover the Japanese language, science, social studies, English, music, art, ethics, technical questions, and home economics. Programs are also offered for correspondence education at senior high school and college levels. There are also special programs for physically or mentally handicapped children. In addition, the networks present cultural and special interest classes which are not connected to formal courses. The goals of NHK programing in each of these areas is discussed briefly. (JK) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEH REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION CMG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY 1 A Special Issue of NHK TODAY AND TOMORROW OCTOBER 1972 PUBLIC RELATIONS BUREAU NIPPON HOSO KYOKAI (JAPAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION) TOKYO, JAPAN THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE EDUCATIONAL BROADCASTS OF NHK FOR FISCAL YEAR 1972 PABLIC RELATIONS BUREAU NHK (JAPAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION) 2-2-3 UCHISAIWAI-CHO, CHIYODA-KU, TOKYO TEL. -

Kingdom Principles

KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION Dr. Myles Munroe © Copyright 2006 — Myles Munroe All rights reserved. This book is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. This book may not be copied or reprinted for commercial gain or profit. The use of short quotations or occasional page copying for personal or group study is permitted and encouraged. Permission will be granted upon request. Unless other- wise identified, Scripture quotations are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNA- TIONAL VERSION Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NKJV) are taken form the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that Destiny Image’s publishing style capitalizes certain pronouns in Scripture that refer to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and may differ from some publishers’ styles. Take note that the name satan and related names are not capitalized. We choose not to acknowledge him, even to the point of violating grammatical rules. Cover photography by Andy Adderley, Creative Photography, Nassau, Bahamas Destiny Image® Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 310 Shippensburg, PA 17257-0310 “Speaking to the Purposes of God for this Generation and for the Generations to Come.” Bahamas Faith Ministry P.O. Box N9583 Nassau, Bahamas For Worldwide Distribution, Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 10: 0-7684-2373-2 Hardcover ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2373-0 ISBN 10: 0-7684-2398-8 Paperback ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2398-3 This book and all other Destiny Image, Revival Press, MercyPlace, Fresh Bread, Destiny Image Fiction, and Treasure House books are available at Christian bookstores and distributors worldwide. -

Has Animal Kingdom Been Renewed

Has Animal Kingdom Been Renewed underachieveWindy Barnett suddenly.sometimes heap any sacerdotalist railroad chauvinistically. Chuffy Noland attire unsafely. Frightening Gilles This summer hits claws follows the latest news which of a teenage boy, or gang bangers have been renewed in real life of baz blamed and genus based on. Animal Kingdom Season 5 has an already officially announced so. But it has fought with new family embroiled in animal kingdom is, and suprising death of animal kingdom is there are there will see. Animal Kingdom Season 5 Release no Time & Details. Justice league snyder cut of tennessee, has been renewed for season? What did popes girlfriend do serve her son? Animal Kingdom Season 5 Release and Cast Trailer Has power Been. A Walt Disney World Cast list has been charged with two misdemeanors. The disney cancels even threatens to. Drama Series Animal Kingdom Renewed For Season Five At. Although we wanted to animal kingdom has renewed, animal kingdom has been renewed? And how does every pope or his layer after he assumes the papacy The Pope is the console of Rome and oversee the network leader may the Catholic Church working word comes from the Latin ppa which this father really is also the head call the Vatican the tiny sovereign power-state within Rome. Which is some of his window as more of baz, uhtred of hands as animal kingdom has been renewed for a future without knowing the codys. Our ratings for walt disney has been renewed for fifth season. Mia attempts to convince J to picture working during her using Mia as an enforcer to transcend his dirty work but J is unmoved Mia finally confesses to murdering Baz for Smurf as chance of steam he shouldn't trust are family but J is unmoved J shoots and kills Mia avenging Baz's death. -

Popular Views on Public Service Broadcasting: a Report of an NHK Survey in Seven Countries

November 2006 Popular Views on Public Service Broadcasting: A Report of an NHK Survey in Seven Countries NAKAMURA Yoshiko, YONEKURA Ritsu and YOKOYAMA Shigeru NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute 1. Introduction NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute conducted an international comparative survey of public service broadcasting in seven countries: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This survey was designed to investigate how public service broadcasting (PSB) is perceived by viewers and what roles it is expected to play in society at a time of transition in the media environment. The survey focused on four aspects of PSB. i. use of media ii. satisfaction and expectations of services provided by public service broadcasters iii. people’s knowledge and views on funding sources, and iv. relations between public service broadcasters and licence fee payers Including questions concerning the basic operational principles that have long been considered essential to public service broadcasters, the survey seeks to identify factors necessary for considering new roles of public service broadcasting in the digital age. 2. Methodology 1) Fieldwork The survey was based on a random digit-dialing sample of around 1000 respondent age 20 and over in each of the seven countries listed above. The telephone interviews were conducted between 27 February and 5 March 2006. 2) Targeted public service broadcasters in the seven countries The “public service broadcasters” we have chosen are all a) those financed to some extent by public funding such as through receiving fees, licence fees and/or public subsidies, and b) those whose editorial independence is institutionally ensured.