Running On: Conservation of Migratory Fishes on Long Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Atlantic Menhaden Ecological Reference Points

Review of Atlantic Menhaden Ecological Reference Points Steve Cadrin July 27 2020 The Science Center for Marine Fisheries (SCeMFiS) requested a technical review of analyses being considered by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) to estimate ecological reference points (ERPs) for Atlantic menhaden by applying a multispecies model (SEDAR 2020b). Two memoranda by the ASMFC Ecological Reference Point Work Group and Atlantic Menhaden Technical Committee were reviewed: • Exploration of Additional ERP Scenarios with the NWACS-MICE Tool (April 29 2020) • Recommendations for Use of the NWACS-MICE Tool to Develop Ecological Reference Points and Harvest Strategies for Atlantic Menhaden (July 15 2020) Summary • According to the SEDAR69 Ecological Reference Points report, the multi-species tradeoff analysis suggests that the single-species management target for menhaden performs relatively well for meeting menhaden and striped bass management objectives, and there is little apparent benefit to striped bass or other predators from fishing menhaden at a lower target fishing mortality. • Revised scenarios of the SEDAR69 peer-reviewed model suggest that results are highly sensitive to assumed conditions of other species in the model. For example, reduced fishing on menhaden does not appear to be needed to rebuild striped bass if other stocks are managed at their targets. • The recommendation to derive ecological reference points from a selected scenario that assumes 2017 conditions was based on an alternative model that was not peer reviewed by SEDAR69, and the information provided on alternative analyses is insufficient to determine if it is the best scientific information available to support management decisions. • Considering apparent changes in several stocks in the multispecies model since 2017, ecological reference points should either be based on updated conditions or long-term target conditions. -

Marine Fish and Invertebrates: Biology and Harvesting Technology - R

FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE – Vol. II - Marine Fish and Invertebrates: Biology and Harvesting Technology - R. Radtke MARINE FISH AND INVERTEBRATES: BIOLOGY AND HARVESTING TECHNOLOGY R. Radtke University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Hawai’i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, Honolulu, USA Keywords: fisheries, trophic, harvesting, fecundity, management, species, equilibrium yield, biomass, stocks, otoliths, calcified tissues, teleost fishes, somatic growth, population, recruitment, mortality, population, cation and anion densities, genotype, acoustic biomass estimation, aquaculture, ecosystems, anthropogenic, ecological, diadromous species, hydrography, Phytoplankton, finfish, pelagic, demersal, exogenous, trophic, purse seines, semidemersal, gadoid, morphometrics, fecundity, calanoid, copepods, euphausiids, caudal fin, neritic species, epibenthic, epipelagic layers, thermocline, nacre, benthepelagic, discards, pots. Contents 1. Introduction 2. New Approaches 3. Biology and Harvesting of Major Species 3.1. Schooling Finfish (Cods, Herrings, Sardines, Mackerels, and others) 3.2. Tunas, Billfish and Sharks 3.3. Shrimp and Krill 3.4. Crabs and Lobsters 3.5. Shelled Molluscs (Clams, Oysters, Scallops, Pearl Oysters, and Abalone) 3.6. Cephalopods: Octopus and Squid 3.7. Orange Roughy and Other Benthic Finfish 3.8. Flatfishes and Skates 4. Marine Plants: Production and Utilization 5. Commercial Sea-Cucumbers and Trepang Markets 6. Importance of Non-Commercial Fish 7. The Problem of Discards in Fisheries 8. Fisheries Engineering and Technology: Fishing Operation and Economic Considerations 9. Subsistence Hunting of Marine Mammals GlossaryUNESCO – EOLSS Bibliography Biographical Sketch SAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary The technology to understand and harvest fishery resources has expanded markedly in recent times. This expansion in information has allowed the harvesting of new species and stocks. Information is important to preservation and responsible harvesting. For managers and project organizers alike, knowledge is the cornerstone to successful fishery resource utilization. -

Menhadentexasfull.Pdf Ocean Associates, Incorporated Oceans and Fisheries Consulting

Ocean Associates, Inc. Ocean Associates, Inc. Phone: 703-534-4032 4007 N. Abingdon Street Fax: 815-346-2574 Arlington, Virginia USA 22207 Email: [email protected] http://www.OceanAssoc.com March 24, 2008 Toby M. Gascon Director of Government Affairs Omega Protein, Inc. Ref: Gulf of Mexico Menhaden: Considerations for Resource Management Dear Mr. Gascon, In response to your Request for Scientific Analysis regarding proposed regulations for menhaden fishing in Texas waters, herewith is our response to your questions. We have formatted it as a report. It includes a Preface, which sets the stage, an Executive Summary without citations, and a response to each of the questions with supporting citations. We have enclosed a copy of the paper (Condrey 1994) we believe was used by TPWD in drafting the proposed regulations. It has the appropriate underlying numbers and is the only study with sufficient detail to be used for the type of analysis attempted by TPWD. We appreciate the opportunity to provide this analysis. It came at an opportune time. I have been developing the ecosystem material included in this document for many years, ever since the basic theory was proposed to me by a Russian colleague who went on to become the Soviet Minister of Fisheries. As Chief of the NMFS Research Division, I read countless documents regarding fisheries research and management, and attended many conferences and program reviews, slowly gaining the knowledge reflected in this report. The flurry of menhaden writings and government actions gave me impetus to complete the work, and your request accelerated it further. I expect the ecosystem materials in this present report will soon be part of a more- detailed formal scientific paper documenting the role of menhaden in coastal ecology. -

The Diet of Chesapeake Bay Ospreys and Their Impact on the Local Fishery

]. RaptorRes. 25(4):109-112 ¸ 1991 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. THE DIET OF CHESAPEAKE BAY OSPREYS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE LOCAL FISHERY PETER K. MCLEAN • AND MITCHELL A. BYRD Departmentof Biology,College of William and Mary, Williamsburg,VA 23785 ABSTRACT.--Ospreys(Pan dion haliaetus), were observedat sevennests located in southwesternChesapeake Bay, for 642 hr between21 May and 25 July 1985. On average5.4 fish/day were deliveredto the nests. The size of fish deliveredranged from 4 to 43 cm, and the mean weight of fish deliveredwas 156.9 g. Atlantic Menhaden (Brevortiatyrannus) accounted for nearly 75% of the diet, although White Perch (Motone americana),Atlantic Croaker (Micropogoniasundulatus), Oyster Toadfish (Opsanustau), and American Eel (Anguilla rostrata)also were commonprey. ChesapeakeBay Ospreys,estimated at 3000 breedingpairs, would be expectedto eat about 132 171 kg of fish during the 52-day nestlingperiod. This "harvest"represents 0.004% of the annual ChesapeakeBay commercialharvest and likely has a minimal impact on the local fishery. La dietade fixguila Pescadora (Pan dion haliaetus) en la BahiaChesapeake y su impacto en la pescalocal EXTR^CTO.--fixguilasPescadoras (Pandion haliaetus) en sietenidos ubicados en la zonasudoeste de la Bahia Chesapeake,fueron observadas por 642 horasentre el 21 de mayo y el 25 de julio de 1985. Un promediode 5.4 pesces/diafueron 11evadosa cada nido. E1 tamafio del pescadoque rue 11evadoal nido oscil6entre 4 y 43 cm, y el pesomedio fue de 156.9 g. Los pecesde la especieBrevortia tyrannus constituyeroncerca del 75% de la dieta,aunque peces de las especiesMorone americana, Microp.ogonias undulatus,Opsanus tau, Anguilla rostrata tambign fueron presa comfin. -

A Recommendation to Amend the Atlantic Menhaden Fishery

A Recommendation to Amend the Atlantic Menhaden Fishery Management Plan To Protect and Preserve Menhaden's Ecological Role in Chesapeake Bay and Throughout its Range Presented to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission December 17,2003 by the National Coalition for Marine Conservation Leesburg, Virginia "In the long run, I look forward to the day when fishery conservation and management are carried out with full knowledge of the interactions between the managed species and the living and nonliving components of their environment. I believe we are making steady progress toward the goal of an ecosystem approach to management. "In recent years, we have begun to move away from single species concepts of management, like maximum sustainable yield, and toward the multispecies concept of optimum yield. Optimum yield encourages the consideration of ecological factors in devising management strategies, as well as economic and social factors. Within a few years, I expect that most fishery management plans prepared by the Regional Fishery Management Councils will be multispecies plans, which will take into account predator-prey relationships in particular. Not too long after that, I hope we will use an ecosystem approach to fishery management." This statement was part of the keynote remarks by then-NOAA Administrator Richard Frank at a Striped Bass Symposium sponsored by the National Coalition for Marine Conservation in March 1980. In spite of Dr. Frank's optimism, we've only begun to take the first tentative steps toward an ecosystem approach to managing marine fisheries during the last several years, primarily due to the recommendations of the 1999 Report to Congress of the Ecosystems Principles Advisory Panel. -

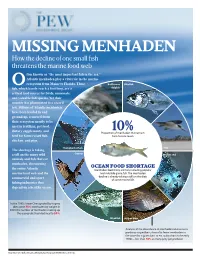

Missing Menhaden

MISSING MENHADEN How the decline of one small fish threatens the marine food web ften known as “the most important fish in the sea,” Atlantic menhaden play a vital role in the marine ecosystem from Maine to Florida. These Bottlenose Bluefish O dolphin fish, which barely reach a foot long, are a critical food source for birds, mammals, and valuable fish species. Yet their number has plummeted to a record low. Billions of Atlantic menhaden have been hauled in and ground up, removed from their ecosystem mostly to be used in fertilizer, pet food, dietary supplements, and 10% Proportion of menhaden that remain feed for farm-raised fish, from historic levels chicken, and pigs. Humpback whale Tern The shortage is taking a toll on the many wild Osprey Harbor seal animals and fish that eat menhaden, threatening OCEAN FOOD SHORTAGE the entire Atlantic Menhaden feed many animals, including popular marine food web and the and valuable game fish. The menhaden commercial and sport decline is already taking a toll on the diets of some marine life. fishing industries that depend on a healthy ocean. In the 1980s, lower Chesapeake Bay osprey diets were 75% menhaden by weight; in 2009, the number of menhaden making up the osprey diet had declined to 24%. Weakfish Striped bass Analysis of the abundance of menhaden relative to its predator, striped bass, shows far fewer menhaden in the water for a given bass to eat today than in the early 1980s – less than 10% as many prey per predator. Osprey photo: Gallo Images; other photos this page: WikiMedia Commons MENHADEN’S PLIGHT l Populations have plummeted 88 percent during the past 25 years. -

As Piscivorous Top Predators, Ospreys (Pandion Haliaetus) Are Not Only

Broad Spatial Trends in Osprey Provisioning, Reproductive Success, and Population Growth within Lower Chesapeake Bay Kenneth Andrew Glass Acworth, Georgia Bachelor of Science, Berry College, 2000 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science Department of Biology The College of William and Mary January, 2008 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Kenneth Andrew Glass Approved by the Committee, September, 2007 Committee Chair Research Associate Professor Bryan Watts The College of William & Mary Chancellor Professor of Biology Mitchell Byrd The College of William & Mary Associate Professor John Swaddle The College of William & Mary Professor Stewart Ware The College of William & Mary ABSTRACT PAGE Since the banning of DDT in 1972, the Chesapeake Bay osprey (Pandion haliaetus) population has recovered remarkably. However, spatial variation in the population growth rate was revealed by a Bay-wide survey conducted in 1995 and 1996. Generally, the highest rates had occurred in the upper estuarine areas while the slowest rates had occurred in the lower estuarine areas. Indications of food stress have been previously documented along the Bay proper, and reduced reproductive success has been recently observed in the same locale. To what extent food availability might be influencing population dynamics on a broad scale in the Bay is currently unknown. We hypothesized that the spatial variation in the population growth rate of ospreys in Chesapeake Bay reflected, in large part, differences in reproductive success mediated through the ability of parents to provision young. -

Diet Composition of Young-Of-The-Year Bluefish in the Lower Chesapeake Bay and the Coastal Ocean of Virginia

Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 135:371–378, 2006 [Note] Ó Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 2006 DOI: 10.1577/T05-033.1 Diet Composition of Young-of-the-Year Bluefish in the Lower Chesapeake Bay and the Coastal Ocean of Virginia JAMES GARTLAND,* ROBERT J. LATOUR,AIMEE D. HALVORSON, AND HERBERT M. AUSTIN Department of Fisheries Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Post Office Box 1346, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, USA Abstract.—The lower Chesapeake Bay and coastal ocean of from the coastal waters (Baird 1873; Bigelow and Virginia serve as an important nursery area for bluefish Schroeder 1953). Recent trends in biomass estimates Pomatomus saltatrix. Describing the diet composition of and landings have raised concerns that the stock is young-of-the-year (hereafter, age-0) bluefish in this region is currently in a period of decline (Lewis 2002). Factors essential to support current Chesapeake Bay ecosystem including overfishing, declining habitat quality and modeling efforts and to contribute to the understanding of reproductive success, altered migratory patterns, com- the foraging ecology of these fish along the U.S. Atlantic petition with increased populations of striped bass coast. The stomach contents of 404 age-0 bluefish collected Morone saxatilis, and shifts in feeding ecology have from the lower Chesapeake Bay and adjacent coastal zone in 1999 and 2000 were examined as part of a diet composition been identified as possible causes of these trends study. Age-0 bluefish foraged primarily on bay anchovies (MAFMC 1998). Anchoa mitchilli, striped anchovies Anchoa hepsetus, and The perception of a decline in the abundance of Atlantic silversides Menidia menidia. -

Atlantic Menhaden Workshop Proceedings

Special Report No. 83 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Working towards healthy, self-sustaining populations for all Atlantic coast fish species or successful restoration well in progress by the year 2015 Atlantic Menhaden Workshop Report & Proceedings December 2004 Atlantic Menhaden Workshop Report & Proceedings A report of a workshop conducted by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission October 12 – 14, 2004 Alexandria, VA Funding for the workshop and publication was made possible through a purchase order from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Marine Fisheries Service No. DG133F04CN0143 and from a grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA04MF4740186. December 2004 Acknowledgements The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission would like to thank those that planned and attended this workshop, particularly Steering Committee members -- Jack Travelstead, Matthew Cieri, Dick Brame, Toby Gascon, Bill Goldsborough, Steve Meyers, Niels Moore, Amy Schick, and Bill Windley. The Commission expresses its appreciation to all the workshop presenters, including, Kyle Hartman, John Jacobs, Jim Uphoff, Laura Lee, Gary Nelson, Doug Vaughan, Rob Latour, Bob Wood, Charles Madenjian, and Ed Houde. In addition, the Commission thanks the staff who coordinated the workshop, Robert Beal and Nancy Wallace, as well as Carrie Selberg and Megan Gamble for recording the workshop proceedings. The Commission especially thanks Jack Travelstead and Matthew Cieri for co-chairing this workshop. ii Executive Summary In October 2004, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (Commission) held a workshop to examine the status of Atlantic menhaden with respect to its ecological role. This workshop was convened in response to a motion made by the Atlantic Menhaden Management Board in May 2004. -

Brevoortia Tyrannus

Atlantic Menhaden − Brevoortia tyrannus Overall Vulnerability Rank = Moderate Biological Sensitivity = Low Climate Exposure = Very High Data Quality = 88% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Brevoortia tyrannus Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Low Moderate Stock Status 2.4 1.4 High Other Stressors 2.1 2.4 Very High Population Growth Rate 1.2 2.8 Spawning Cycle 1.8 2.8 Complexity in Reproduction 1.9 3.0 Early Life History Requirements 2.9 2.9 Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 1.8 2.4 Prey Specialization 1.5 3.0 Habitat Specialization 2.0 3.0 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Temperature 1.5 3.0 Adult Mobility 1.6 3.0 Dispersal & Early Life History 1.8 3.0 Sensitivity Score Low Sea Surface Temperature 4.0 3.0 Variability in Sea Surface Temperature 1.0 3.0 Salinity 2.4 3.0 Variability Salinity 1.2 3.0 Air Temperature 4.0 3.0 Variability Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Precipitation 1.2 3.0 Variability in Precipitation 1.3 3.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Exposure variables Variability in Ocean Acidification 1.0 2.2 Currents 2.0 1.0 Sea Level Rise 1.5 1.5 Exposure Score Very High Overall Vulnerability Rank Moderate Atlantic Menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: Moderate (64% certainty from bootstrap analysis). Climate Exposure: Very High. Three exposure factors contributed to this score: Ocean Surface Temperature (4.0), Ocean Acidification (4.0) and Air Temperature (4.0). Exposure to all three factors occur during all life stages. -

Atlantic Coast Feeding Habits of Striped Bass: a Synthesis Supporting a Coast-Wide Understanding of Trophic Biology

Fisheries Management and Ecology, 2003, 10, 349–360 Atlantic coast feeding habits of striped bass: a synthesis supporting a coast-wide understanding of trophic biology J. F. WALTER, III Department of Fisheries Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, VA, USA A. S. OVERTON USGS, MD Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, University of Maryland, MD, USA K. H. FERRY Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, Gloucester, MA, USA M. E. MATHER Massachusetts Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Natural Resources Conservation, USGS, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Abstract The recent increase in the Atlantic coast population of striped bass, Morone saxatilis (Walbaum), prompted managers to re-evaluate their predatory impact. Published and unpublished diet data for striped bass on the Atlantic Coast of North America were examined for geographical, ontogenetic and seasonal patterns in the diet and to assess diet for this species. Diets of young-of-the-year (YOY) striped bass were similar across the Upper Atlantic (UPATL), Chesapeake and Delaware Bays (CBDEL) and North Carolina (NCARO) areas of the Atlantic coast where either fish or mysid shrimp dominate the diet. For age one and older striped bass, cluster analysis partitioned diets based on predominance of either Atlantic menhaden, Brevoortia tyrannus (Latrobe), characteristic of striped bass from the CBDEL and NCARO regions, or non-menhaden fishes or invertebrates, characteristic of fish from the UPATL, in the diet. The predominance of invertebrates in the diets of striped bass in the UPATL region can be attributed to the absence of several important species groups in Northern waters, particularly sciaenid fishes, and to the sporadic occurrences of Atlantic menhaden to UPATL waters. -

Bluefish Pomatomus Saltatrix

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix Contributors (2014): Joseph C. Ballenger (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Bluefish are a coastal, pelagic species of interest to fisheries that are often encountered in South Carolina estuarine and coastal waters. Taxonomy and Basic Description Bluefish, Pomatomus saltatrix (Linnaeus 1766), is a member of the monotypic family (family represented by single species) Pomatomidae (bluefishes). This family is found within the order Perciformes, the most diversified of all fish orders and largest order of vertebrates (Collette 2002; Nelson 2006). Within the order Perciformes, they are found within the suborder Percoidei (largest suborder of the Perciformes) and superfamily Percoidea (Nelson 2006). The species is similar in appearance to some members of the families Carangidae and Rachycentridae occurring in the western Atlantic (Collette 2002). It differs from the most superficially similar carangid, Seriola (amberjacks), because Seriola have bands of villiform teeth in jaws (Collette 2002). Bluefish are a large species (to 1 m or 3 ft.) with a sturdy, compressed body and large head with prominent, sharp, compressed teeth in a single series (Collette 2002). The jaw is terminal, with the lower jaw sometimes slightly projecting (Collette 2002). As is common in most other members of the suborder Percoidei (Nelson 2006), bluefish possess two dorsal fins, the first being short and composed of 7 to 8 weak spines connected by a membrane and the second long, with one spine and 23-28 soft rays (Collette 2002). The pectoral fins are short, not reaching the origin of the soft dorsal fin (Collette 2002). Bluefish possess small scales that cover the head, body, and bases of vertical fins; the lateral line is almost straight (Collette 2002).