Optimistic Evolutionists: the Progressive Science and Religion of Joseph Leconte, Henry Ward Beecher, and Lyman Abbott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

Sierra Club Members Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4j49n7st No online items Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Processed by Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant; machine-readable finding aid created by Brooke Dykman Dockter The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History --History, CaliforniaGeographical (By Place) --CaliforniaSocial Sciences --Urban Planning and EnvironmentBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --ForestryBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --Wildlife ManagementSocial Sciences --Sports and Recreation Guide to the Sierra Club Members BANC MSS 71/295 c 1 Papers Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Collection number: BANC MSS 71/295 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant Date Completed: 1992 Encoded by: Brooke Dykman Dockter © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Sierra Club Members Papers Collection Number: BANC MSS 71/295 c Creator: Sierra Club Extent: Number of containers: 279 cartons, 4 boxes, 3 oversize folders, 8 volumesLinear feet: ca. 354 Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. -

Yosemite: Warming Takes a Toll

Bay Area Style Tuolumne County Gives Celebrating Wealthy renowned A guide to donors’ S.F. retailer autumn’s legacies Wilkes best live on Bashford’s hiking, through Island Style ever-so- climbing their good Unforgettable Hawaiian adventures. K1 stylish and works. N1 career. J1 biking. M1 SFChronicle.com | Sunday, October 18,2015 | Printed on recycled paper | $3.00 xxxxx• Airbnb measure divides neighbors Prop. F’s backers, opponents split come in the middle of the night, CAMPAIGN 2015 source of his income in addition bumping their luggage down to work as a real estate agent over impact on tight housing market the alley. This is not an occa- and renewable-energy consul- sional use when a kid goes to ing and liability issues. tant, Li said. college or someone is away for a But Li, 38, said he urges “I depend on Airbnb to make By Carolyn Said Phil Li, who rents out three week. Along with all the house guests to be respectful, while sure I can meet each month’s suites to travelers via Airbnb. cleaners, it’s an array of com- two other neighbors said that expenses,” he said. “I screen A narrow alley separates “He’s running a hotel next mercial traffic in a residential they are not affected. Vacation guests carefully and educate Libby Noronha’sWest Portal door,” said Noronha, 67,a re- neighborhood,” she said of the rentals helped him after he lost them to come and go quietly.” house from that of her neighbor tired federal employee. “People noise, smoking, garbage, park- his job and remain a major Prop. -

Peaks and Professors

Ann Lage • THE PEAKS AND THE PROFESSORS THE PEAKS AND THE PROFESSORS UNIVERSITY NAMES IN THE HIGH SIERRA Ann Lage DURING THE LAST DECADE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, a small group of adven- turesome university students and professors, with ties to both the University of California and Stanford, were spending their summers exploring the High Sierra, climbing its highest peaks, and on occasion bestowing names upon them. Some they named after natural fea- tures of the landscape, some after prominent scientists or family members, and some after their schools and favored professors. The record of their place naming indicates that a friendly rivalry between the Univer- sity of California in Berkeley and the newly established Stanford University in Palo Alto was played out among the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada, just as it was on the “athletic fields” of the Bay Area during these years. At least two accounts of their Sierra trips provide circum- stantial evidence for a competitive race to the top between a Cal alumnus and professor of engineering, Joseph Nisbet LeConte, and a young Stanford professor of drawing and paint- ing, Bolton Coit Brown. Joseph N. LeConte was the son of professor of geology Joseph LeConte, whose 1870 trip with the “University Excursion Party” to the Yosemite region and meeting with John Muir is recounted elsewhere in this issue.1 “Little Joe,” as he was known, had made family trips to Yosemite as a boy and in 1889 accompanied his father and his students on a trip University Peak, circa 1899. Photograph by Joseph N. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-9041 MAYO, Dwight Eugene, 1919- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IDEA OF THE GEOSYNCLINE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1968 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 'i hii UIUV&Hüil Y OF O&LAÜOM GRADUAS ü COLLEGE THS DEVlïLOFr-ÎEKS OF TÜE IDEA OF SHE GSOSÏNCLIKE A DISDER'i'ATIOH SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUAT E FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY DWIGHT’ EUGENE MAYO Norman, Oklahoma 1968 THE DEVELOfMEbM OF THE IDEA OF I HE GEOSÏHCLINE APPROVED BÏ DIS5ERTAII0K COMMITTEE ACKNOWL&DG EMEK3S The preparation of this dissertation, which is sub mitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the University of Okla homa, has been materially assisted by Professors Duane H, D. Roller, David b, Kitts, and Thomas M. Smith, without whose help, advice, and direction the project would have been well-nigh impossible. Acknowledgment is also made for the frequent and generous assistance of Mrs. George Goodman, librarian of the DeGolyer Collection in the history of Science and Technology where the bulk of the preparation was done. ___ Generous help and advice in searching manuscript materials was provided by Miss Juliet Wolohan, director of the Historical Manuscripts Division of the New fork State Library, Albany, New fork; Mr. M. D. Smith, manuscripts librarian at the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Dr. Kathan Seingold, editor of the Joseph Henry Papers, bmithsonian Institution, Wash ington, D. -

Henry Larcom Abbot 1831-1927

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XIII FIRST MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF HENRY LARCOM ABBOT 1831-1927 BY CHARLES GREELEY ABBOT PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1929 HENRY LARCOM ABBOT 1831-1927 BY CHARGES GREKLEY ABBOT Chapter I Ancestry Henry Larcom Abbot, Brigadier General, Corps of Engi- neers, U. S. Army, member of the National Academy of Sciences, was born at Beverly, Essex County, Massachusetts, August 13, 1831. He died on October 1, 1927, at Cambridge, Massachusetts, aged 96 years. He traced his descent in the male line from George Abbot, said to be a native of Yorkshire, England, who settled at Andover, Massachusetts, in the year 1642. Through early intermarriage, this line is closely con- nected with that of the descendants of George Abbott of Row- ley, Essex County, Massachusetts. The Abbots of Andover were farmers, highly respected by their townsmen, and often intrusted with elective office in town, church, and school affairs. In the fifth generation, de- scended through John, eldest son of George Abbot of An- dover,1 Abiel Abbot, a great-grandfather of General Abbot, removed from Andover to settle in Wilton, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, in the year 1763. He made his farm from the wilderness on "Abbot Hill" in the southern part of the township. Having cleared two acres and built a two-story house and barn, he married Dorcas Abbot and moved into the house with his bride before the doors were hung, in November, 1764. They had thirteen children, of whom the fourth, Ezra Abbot, born February 8, 1772, was grandfather to our propo- s^tus. -

The Geologists' Frontier

Vol. 30, No. 8 AufJlIt 1968 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT Of GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES State of Oregon Department of Geology The ORE BI N and Mineral Industries Volume30, No.8 1069 State Office Bldg. August 1968 Portland Oregon 97201 FIREBALLS. METEORITES. AND METEOR SHOWERS By EnNin F. Lange Professor of General Science, Portland State College About once each year a bri lIiant and newsworthy fireball* passes across the Northwest skies. The phenomenon is visible evidence that a meteorite is reach i ng the earth from outer space. More than 40 percent of the earth's known meteorites have been recovered at the terminus of the fireball's flight. Such meteorites are known as "falls" as distinguished from "finds," which are old meteorites recovered from the earth's crust and not seen falling. To date only two falls have been noted in the entire Pacific North west. The more recent occurred on Sunday morning, July 2, 1939, when a spectacular fireball or meteor passed over Portland just before 8:00 a.m. Somewhat to the east of Portland the meteor exploded, causing many people to awaken from their Sunday morning slumbers as buildings shook, and dishes and windows rattled. No damage was reported. Several climbers on Mount Hood and Mount Adams reported seei ng the unusual event. The fireball immediately became known as the Portland meteor and stories about it appeared in newspapers from coast to coast. For two days th e pre-Fourth of July fireworks made front-page news in the local newspapers. J. Hugh Pruett, astronomer at the University of Oregon and Pacific director of the American Meteor Society, in an attempt to find the meteor ite which had caused such excitement, appealed to all witnesses of the event to report to him their observations. -

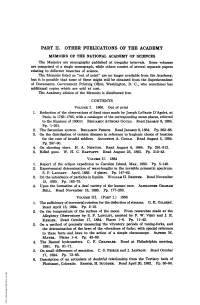

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2. -

NAMING a NEW GEOLOGICAL ERA: the ECOZOIC ERA, ITS MEANING and HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS by Allysyn Kiplinger

NAMING A NEW GEOLOGICAL ERA: THE ECOZOIC ERA, ITS MEANING AND HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS By Allysyn Kiplinger 1. Introduction The universe gropes its way forward in fits and starts, progressing by trial and error through a multiplicity of attempts and efforts, moving in many directions as it looks for a breakthrough to leap forward in evolution and consciousness.1 This is how Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin described evolutionary progress. Indeed, the universe seems to be Allysyn Kiplinger is the editor of the website www.ecozoictimes. Her bio is available at http://ecozoictimes.com/about/. 1Teilhard uses “groping” “to express the idea of progression by trial and error. Multiplicity of attempts, efforts, in many different directions, preparing a breakthrough and forward leap.” It is a “Teilhardian keyword.” Sion Cowell, The Teilhard Lexicon (Brighton, England: Sussex Academic Press, 2001), 89. groping now for a breakthrough in human consciousness leading to a new geological era in the history of planet Earth. Thomas Berry named this new era the “Ecozoic Era.” In this article I share my personal and intellectual journey of discovery of this emerging era. I offer the etymology and the story of how the word was invented, its relationship to geology, and the 19th century terms and milieu that preceded it. I also offer a discussion of contemporary humans’ relationship to deep time, and the possibility of humans directing geology in a mutually enhancing manner. My ultimate intent is to contribute to the development of a richer vocabulary with which to value life, Earth community, and human- Earth relations. 2. -

A Historical Examination of the Protestant Stewardship Theological Principle

“AND THE GREAT DRAGON WAS THROWN DOWN:” A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF THE PROTESTANT STEWARDSHIP THEOLOGICAL PRINCIPLE BY HANNAH M JAMES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Religious Studies May, 2018 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Lucas Johnston, Ph.D., Advisor Stephen Boyd, Ph.D., Chair John Ruddiman, Ph.D. ii Table of Contents ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................. III INTRODUCTION: DEMYSTIFYING A MEMORY ........................................................................ IV SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................. V METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................... VI PART I: HISTORICAL THEOLOGICAL STANDARDS OF STEWARDSHIP ............................ 1 JUSTIFICATION LITERATURE .................................................................................................................... 3 THE UNLIMITED ABUNDANCE OF NATURE ...................................................................................... 6 AMERICAN INDIAN RELIGIOSITY ............................................................................................................ -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title LECONTE,JOSEPH - GENTLE PROPHET OF EVOLUTION - STEPHENS,LD Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3w21n20n Journal ANNALS OF SCIENCE, 41(2) ISSN 0003-3790 Author AYALA, FJ Publication Date 1984 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ANNALS OF SCIENCE, 41 (1984), 181 202 Book Reviews Editions and Selections SrILLMAN DRAKE,Cause, experiment and science. A Galilean dialogue incorporating a new English translation of Galileo's 'Bodies That Stay atop Water, or Move in It'. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1981. xxix + 237 pp. s Consider a life-long student of Galileo who plans to translate a work of his into English. Consider also that, to make the text entirely understandable to non specialized readers, he associates to his translation many introductory and explanatory data. Thirdly, since that work (the Diseorso intorno alle cose, che stanno in su racqua, o che in quella si muovono) is one of the less carefully studied, the student also takes his opportunity to declare its importance in the forming of Galileo's thought and in the very origin of modern science. Moreover, he extends himself to discuss conceptual aspects which he thinks to be peculiar to the book and to its author's practice of science. Then, if such a student is Stillman Drake, whose convictions on this subject sometimes differ sharply from those of other authoritative historians, the temptation is strong for him to underline alternatives in interpretation and to point to elements supporting his own. -

The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California

The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California Barbara Ertter Reprinted from Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences Volume 55, Supplement I, Article 4, pp. 58-87 Copyright © 2004 by the California Academy of Sciences Reprinted from PCAS 55(Suppl. I:No. 4):58-87. 18 Oct. 2004. PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Volume 55, Supplement I, No. 4, pp. 58–87, 23 figs. October 18, 2004 The Flowering of Natural History Institutions in California Barbara Ertter University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2465; Email: [email protected] The genesis and early years of a diversity of natural history institutions in California are presented as a single intertwined narrative, focusing on interactions among a selection of key individuals (mostly botanists) who played multiple roles. The California Academy of Sciences was founded in 1853 by a group of gentleman schol- ars, represented by Albert Kellogg. Hans Hermann Behr provided an input of pro- fessional training the following year. The establishment of the California Geological Survey in 1860 provided a further shot in the arm, with Josiah Dwight Whitney, William Henry Brewer, and Henry Nicholas Bolander having active roles in both the Survey and the Academy. When the Survey foundered, Whitney diverted his efforts towards ensuring a place for the Survey collections within the fledgling University of California. The collections became the responsibility of Joseph LeConte, one of the newly recruited faculty. LeConte developed a shared passion for Yosemite Valley with John Muir, who he met through Ezra and Jeanne Carr. Muir also developed a friendship with Kellogg, who became estranged from the Academy following the contentious election of 1887, which was purportedly instigated by Mary Katherine Curran.