JOHN CAMPBELL MERRIAM AS SCIENTIST and PHILOSOPHER CHESTER STOCK California Institute of 'I'echnology Research Associate, 'I'he Carnegie Institution of Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historica Olomucensia 53-2017

HISTORICA OLOMUCENSIA 53–2017 SBORNÍK PRACÍ HISTORICKÝCH XLIII HISTORICA OLOMUCENSIA 53–2017 Sborník prací historických XLIII Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Olomouc 2017 Zpracování a vydání publikace bylo umožněno díky fi nanční podpoře, udělené roku 2017 Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR v rámci Institucionálního roz- vojového plánu, Filozofi cké fakultě Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci. Návaznost, periodicita a anotace: Časopis Historica Olomucensia, Sborník prací historických je vydáván od roku 2009. Na- vazuje na dlouholetou tradici ediční řady Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis – Historica, Sborník prací historických, která začala být vydávána v roce 1960. Od dubna 2015 je zařazen do prestižní evropské databáze odborných časopisů ERIH PLUS (Europe- an Reference Index for the Humanities and the Social Sciences). Od roku 2009 je na se- znamu recenzovaných neimpaktovaných periodik vydávaných v České republice. Od roku 2009 vychází dvakrát ročně, s uzávěrkou na konci dubna a na konci října. Oddíl Články a studie obsahuje odborné recenzované příspěvky věnované různým problémům českých a světových dějin. Oddíl Zprávy zahrnuje především informace o činnosti Katedry historie FF UP v Olomouci a jejích pracovišť či dalších historických pracovišť v Olomouci a případ- ně také životopisy a bibliografi e členů katedry. Posledním oddílem časopisu jsou recenze. Výkonný redaktor a adresa redakce: PhDr. Ivana Koucká, Katedra historie FF UP, tř. Svobody 8, 779 00 Olomouc. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Redakční rada: prof. PhDr. Jana Burešová, CSc. – předseda (Katedra historie FF UP v Olomouci), Mgr. Veronika Čapská, Ph.D. (Katedra obecné antropologie FHS UK v Praze), doc. Mgr. Martin Čapský, Ph.D. (Ústav historických věd Filozofi cko-přírodovědecké fakulty SU v Opavě), prof. -

Remington Kellogg Papers, Circa 1871-1969 and Undated

Remington Kellogg Papers, circa 1871-1969 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: INCOMING AND OUTGOING CORRESPONDENCE, 1916-1969. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY BY CORRESPONDENT...................................... 4 Series 2: INSTITUTIONAL CORRESPONDENCE, 1916-1943. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY................................................................................................... 6 Series 3: INFORMATION FILE, CA. 1871-1933 AND UNDATED. ARRANGED BY SUBJECT.................................................................................................................. 7 Series 4: PHOTOGRAPHS, CA. 1915-1968. ARRANGED CHRONOLOGICALLY............................................................................................. -

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

Sierra Club Members Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4j49n7st No online items Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Processed by Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant; machine-readable finding aid created by Brooke Dykman Dockter The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History --History, CaliforniaGeographical (By Place) --CaliforniaSocial Sciences --Urban Planning and EnvironmentBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --ForestryBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --Wildlife ManagementSocial Sciences --Sports and Recreation Guide to the Sierra Club Members BANC MSS 71/295 c 1 Papers Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Collection number: BANC MSS 71/295 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant Date Completed: 1992 Encoded by: Brooke Dykman Dockter © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Sierra Club Members Papers Collection Number: BANC MSS 71/295 c Creator: Sierra Club Extent: Number of containers: 279 cartons, 4 boxes, 3 oversize folders, 8 volumesLinear feet: ca. 354 Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. -

Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8988d3d No online items Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Brooke M. Black, September 11, 2012. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2012 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: mssPease papers 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Francis Gladheim Pease Papers Dates (inclusive): 1850-1937 Bulk dates: 1905-1937 Collection Number: mssPease papers Creator: Pease, F. G. (Francis Gladheim), 1881- Extent: Approximately 4,250 items in 18 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of the research papers of American astronomer Francis Pease (1881-1938), one of the original staff members of the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Francis Gladheim Pease Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Provenance Deposit, Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington Collection , 1988. -

Yosemite: Warming Takes a Toll

Bay Area Style Tuolumne County Gives Celebrating Wealthy renowned A guide to donors’ S.F. retailer autumn’s legacies Wilkes best live on Bashford’s hiking, through Island Style ever-so- climbing their good Unforgettable Hawaiian adventures. K1 stylish and works. N1 career. J1 biking. M1 SFChronicle.com | Sunday, October 18,2015 | Printed on recycled paper | $3.00 xxxxx• Airbnb measure divides neighbors Prop. F’s backers, opponents split come in the middle of the night, CAMPAIGN 2015 source of his income in addition bumping their luggage down to work as a real estate agent over impact on tight housing market the alley. This is not an occa- and renewable-energy consul- sional use when a kid goes to ing and liability issues. tant, Li said. college or someone is away for a But Li, 38, said he urges “I depend on Airbnb to make By Carolyn Said Phil Li, who rents out three week. Along with all the house guests to be respectful, while sure I can meet each month’s suites to travelers via Airbnb. cleaners, it’s an array of com- two other neighbors said that expenses,” he said. “I screen A narrow alley separates “He’s running a hotel next mercial traffic in a residential they are not affected. Vacation guests carefully and educate Libby Noronha’sWest Portal door,” said Noronha, 67,a re- neighborhood,” she said of the rentals helped him after he lost them to come and go quietly.” house from that of her neighbor tired federal employee. “People noise, smoking, garbage, park- his job and remain a major Prop. -

Carnegie Institution of Washington Monograph Series

BTILL UMI Carnegie Institution of Washington Monograph Series BT ILL UMI 1 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. 1902. Octavo, 16 pp. 2 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. Articles of Incorporation, Deed of Trust, etc. 1902. Octavo, 15 pp. 3 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. Proceedings of the Board of Trustees, January, 1902. 1902. Octavo, 15 pp. 4 CONARD, HENRY S. The Waterlilies: A Monograph of the Genus Nymphaea. 1905. Quarto, [1] + xiii + 279 pp., 30 pls., 82 figs. 5 BURNHAM, S. W. A General Catalogue of Double Stars within 121° of the North Pole. 1906. Quarto. Part I. The Catalogue. pp. [2] + lv + 1–256r. Part II. Notes to the Catalogue. pp. viii + 257–1086. 6 COVILLE, FREDERICK VERNON, and DANIEL TREMBLY MACDOUGAL. Desert Botani- cal Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution. 1903. Octavo, vi + 58 pp., 29 pls., 4 figs. 7 RICHARDS, THEODORE WILLIAM, and WILFRED NEWSOME STULL. New Method for Determining Compressibility. 1903. Octavo, 45 pp., 5 figs. 8 FARLOW, WILLIAM G. Bibliographical Index of North American Fungi. Vol. 1, Part 1. Abrothallus to Badhamia. 1905. Octavo, xxxv + 312 pp. 9 HILL, GEORGE WILLIAM, The Collected Mathematical Works of. Quarto. Vol. I. With introduction by H. POINCARÉ. 1905. xix + 363 pp. +errata, frontispiece. Vol. II. 1906. vii + 339 pp. + errata. Vol. III. 1906. iv + 577 pp. Vol. IV. 1907. vi + 460 pp. 10 NEWCOMB, SIMON. On the Position of the Galactic and Other Principal Planes toward Which the Stars Tend to Crowd. (Contributions to Stellar Statistics, First Paper.) 1904. Quarto, ii + 32 pp. -

Austin Hobart Clark Papers, 1883-1954 and Undated

Austin Hobart Clark Papers, 1883-1954 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 2 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: INCOMING AND OUTGOING CORRESPONDENCE, 1907-1954. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY BY CORRESPONDENT...................................... 5 Series 2: PAPERS DOCUMENTING PARTICIPATION IN OUTSIDE ORGANIZATIONS, 1911-1952. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY BY ORGANIZATION....................................................................................................... 7 Series 3: DIVISION OF ECHINODERMS ADMINISTRATION, N.D. UNARRANGED....................................................................................................... -

Peaks and Professors

Ann Lage • THE PEAKS AND THE PROFESSORS THE PEAKS AND THE PROFESSORS UNIVERSITY NAMES IN THE HIGH SIERRA Ann Lage DURING THE LAST DECADE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, a small group of adven- turesome university students and professors, with ties to both the University of California and Stanford, were spending their summers exploring the High Sierra, climbing its highest peaks, and on occasion bestowing names upon them. Some they named after natural fea- tures of the landscape, some after prominent scientists or family members, and some after their schools and favored professors. The record of their place naming indicates that a friendly rivalry between the Univer- sity of California in Berkeley and the newly established Stanford University in Palo Alto was played out among the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada, just as it was on the “athletic fields” of the Bay Area during these years. At least two accounts of their Sierra trips provide circum- stantial evidence for a competitive race to the top between a Cal alumnus and professor of engineering, Joseph Nisbet LeConte, and a young Stanford professor of drawing and paint- ing, Bolton Coit Brown. Joseph N. LeConte was the son of professor of geology Joseph LeConte, whose 1870 trip with the “University Excursion Party” to the Yosemite region and meeting with John Muir is recounted elsewhere in this issue.1 “Little Joe,” as he was known, had made family trips to Yosemite as a boy and in 1889 accompanied his father and his students on a trip University Peak, circa 1899. Photograph by Joseph N. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-9041 MAYO, Dwight Eugene, 1919- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IDEA OF THE GEOSYNCLINE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1968 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 'i hii UIUV&Hüil Y OF O&LAÜOM GRADUAS ü COLLEGE THS DEVlïLOFr-ÎEKS OF TÜE IDEA OF SHE GSOSÏNCLIKE A DISDER'i'ATIOH SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUAT E FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY DWIGHT’ EUGENE MAYO Norman, Oklahoma 1968 THE DEVELOfMEbM OF THE IDEA OF I HE GEOSÏHCLINE APPROVED BÏ DIS5ERTAII0K COMMITTEE ACKNOWL&DG EMEK3S The preparation of this dissertation, which is sub mitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the University of Okla homa, has been materially assisted by Professors Duane H, D. Roller, David b, Kitts, and Thomas M. Smith, without whose help, advice, and direction the project would have been well-nigh impossible. Acknowledgment is also made for the frequent and generous assistance of Mrs. George Goodman, librarian of the DeGolyer Collection in the history of Science and Technology where the bulk of the preparation was done. ___ Generous help and advice in searching manuscript materials was provided by Miss Juliet Wolohan, director of the Historical Manuscripts Division of the New fork State Library, Albany, New fork; Mr. M. D. Smith, manuscripts librarian at the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Dr. Kathan Seingold, editor of the Joseph Henry Papers, bmithsonian Institution, Wash ington, D. -

The Geologists' Frontier

Vol. 30, No. 8 AufJlIt 1968 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT Of GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES State of Oregon Department of Geology The ORE BI N and Mineral Industries Volume30, No.8 1069 State Office Bldg. August 1968 Portland Oregon 97201 FIREBALLS. METEORITES. AND METEOR SHOWERS By EnNin F. Lange Professor of General Science, Portland State College About once each year a bri lIiant and newsworthy fireball* passes across the Northwest skies. The phenomenon is visible evidence that a meteorite is reach i ng the earth from outer space. More than 40 percent of the earth's known meteorites have been recovered at the terminus of the fireball's flight. Such meteorites are known as "falls" as distinguished from "finds," which are old meteorites recovered from the earth's crust and not seen falling. To date only two falls have been noted in the entire Pacific North west. The more recent occurred on Sunday morning, July 2, 1939, when a spectacular fireball or meteor passed over Portland just before 8:00 a.m. Somewhat to the east of Portland the meteor exploded, causing many people to awaken from their Sunday morning slumbers as buildings shook, and dishes and windows rattled. No damage was reported. Several climbers on Mount Hood and Mount Adams reported seei ng the unusual event. The fireball immediately became known as the Portland meteor and stories about it appeared in newspapers from coast to coast. For two days th e pre-Fourth of July fireworks made front-page news in the local newspapers. J. Hugh Pruett, astronomer at the University of Oregon and Pacific director of the American Meteor Society, in an attempt to find the meteor ite which had caused such excitement, appealed to all witnesses of the event to report to him their observations. -

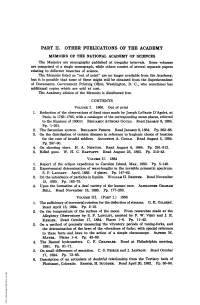

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2.