Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparing Alternative Value Frameworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Better Together TNVR and Public Health APHA 11-13-18.Pdf

Better Together: TNVR and Public Health 11/13/2018 Presenter Disclosures Introduction Better Together TNVR and public health Peter J. Wolf and G. Robert Weedon • TNVR: trap-neuter-vaccinate-return G. Robert Weedon, DVM, MPH Clinical Assistant Professor and Service Head (Retired) Shelter Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine University of Illinois • Emphasis on the “V” Peter J. Wolf, MS Research/Policy Analyst – Vaccination Best Friends Animal Society Have no relationships to disclose • Emphasizes the public health aspect of TNVR programs • Vaccinating against rabies as a means of protecting the health of the public Introduction TNVR TNVR • Why TNVR? • Why TNVR? – The only humane way to – More than half of impounded cats are euthanized deal with the problem of due to shelter crowding, shelter-acquired disease free-roaming (feral, or feral behavior animal welfareTNVR public health community) cats – TNVR, an alternative to shelter impoundment, – When properly applied, improves cat welfare and reduces the size of cat TNVR has been shown to colonies control/reduce populations rabies prevention of free-roaming cats Levy, J. K., Isaza, N. M., & Scott, K. C. (2014). Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption Levy, J. K., Isaza, N. M., & Scott, K. C. (2014). Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. The Veterinary Journal, 201(3), 269–274. of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. The Veterinary Journal, 201(3), 269–274. TNVR TNVR TNVR • Why TNVR? • Why -

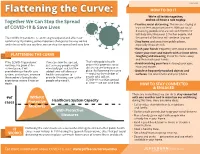

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

Burden of Disease: What Is It and Why Is It Important for Safer Food?

Burden of disease: what is it and why is it important for safer food? What is ‘burden of disease’? Burden of disease is concept that was developed in the 1990s by the Harvard School of Public Health, the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO) to describe death and loss of health due to diseases, injuries and risk factors for all regions of the world.1 The burden of a particular disease or condition is estimated by adding together: • the number of years of life a person loses as a consequence of dying early because of the disease (called YLL, or Years of Life Lost); and • the number of years of life a person lives with disability caused by the disease (called YLD, or Years of Life lived with Disability). Adding together the Years of Life Lost and Years of Life lived with Disability gives a single-figure estimate of disease burden, called the Disability Adjusted Life Year (or DALY). One DALY represents the loss of one year of life lived in full health (see text box for more explanation and examples). Looking at burden of disease using DALYs can reveal surprises about a population’s health. For example, the Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update suggests that neuropsychiatric conditions are the most important causes of disability in all regions of the world, accounting for around 33% of all years lived with disability among adults aged 15 years and over, but only 2.2% of deaths.2 Therefore while psychiatric disorders are not traditionally regarded as having a major impact on the health of populations, this picture is completely altered when the burden of disease is estimated using DALYs. -

WHO COVID-19 Database Search Strategy (Updated 26 May 2021)

Search purpose: Systematic search of the COVID-19 literature performed Monday through Friday for the WHO Database. Search strategy as of 26 May 2021. Searches performed by Tomas Allen, Kavita Kothari, and Martha Knuth. Use following commands to pull daily new entries: Entry_date:( [20210101 TO 20210120]) Entry_date:( 20210105) Duplicates: Duplicates are found in EndNote and Distillr using the Wichor method. Further screening is done by expert reviewers but some duplicates may still be in the database. Daily Search Strategy: Database Daily Search Strategy Medline (coronavir* OR corona virus* OR corona pandemic* OR betacoronavir* OR covid19 OR covid OR (Ovid) nCoV OR novel CoV OR CoV 2 OR CoV2 OR sarscov2 OR sars2 OR 2019nCoV OR wuhan virus* OR 1946- NCOV19 OR solidarity trial OR operation warp speed OR COVAX OR "ACT-Accelerator" OR BNT162b2 OR comirnaty OR "mRNA-1273" OR CoviShield OR AZD1222 OR Sputnik V OR CoronaVac OR "BBIBP-CorV" OR "Ad26.CoV2.S" OR "JNJ-78436735" OR Ad26COVS1 OR VAC31518 OR EpiVacCorona OR Convidicea OR "Ad5-nCoV" OR Covaxin OR CoviVac OR ZF2001 OR "NVX-CoV2373" OR "ZyCoV-D" OR CIGB 66 OR CVnCoV OR "INO-4800" OR "VIR-7831" OR "UB-612" OR BNT162 OR Soberana 1 OR Soberana 2 OR "B.1.1.7" OR "VOC 202012/01" OR "VOC202012/01" OR "VUI 202012/01" OR "VUI202012/01" OR "501Y.V1" OR UK Variant OR Kent Variant OR "VOC 202102/02" OR "VOC202102/02" OR "B.1.351" OR "VOC 202012/02" OR "VOC202012/02" OR "20H/501.V2" OR "20H/501Y.V2" OR "501Y.V2" OR "501.V2" OR South African Variant OR "B.1.1.28.1" OR "B.1.1.28" OR "B.1.1.248" OR -

Defining Malaria Burden from Morbidity and Mortality Records, Self Treatment Practices and Serological Data in Magugu, Babati District, Northern Tanzania

Tanzania Journal of Health Research Volume 13, Number 2, April 2011 Defining malaria burden from morbidity and mortality records, self treatment practices and serological data in Magugu, Babati District, northern Tanzania CHARLES MWANZIVA1*, ALPHAXARD MANJURANO2, ERASTO MBUGI3, CLEMENT MWEYA4, HUMPHREY MKALI5, MAGGIE P. KIVUYO6, ALEX SANGA7, ARNOLD NDARO1, WILLIAM CHAMBO8, ABAS MKWIZU9, JOVIN KITAU1, REGINALD KAVISHE11, WIL DOLMANS10, JAFFU CHILONGOLA1 and FRANKLIN W. MOSHA1 1Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, P. O. Box 2236, Moshi, Tanzania 2Joint Malaria Programme, Moshi, Tanzania 3Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 4Tukuyu Medical Research Centre, Tukuyu, Tanzania 5Tabora Medical Research Centre, Tabora, Tanzania 6Ngongongare Medical Research Station, Usa River, Tanzania 7St. John University of Tanzania, Dodoma, Tanzania 8Amani Medical Research Centre, Muheza, Tanzania 9Magugu Health Centre, Babati, Manyara, Tanzania 10 Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract: Malaria morbidity and mortality data from clinical records provide essential information towards defining disease burden in the area and for planning control strategies, but should be augmented with data on transmission intensity and serological data as measures for exposure to malaria. The objective of this study was to estimate the malaria burden based on serological data and prevalence of malaria, and compare it with existing self-treatment practices in Magugu in Babati District of northern Tanzania. Prospectively, 470 individuals were selected for the study. Both microscopy and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) were used for malaria diagnosis. Seroprevalence of antibodies to merozoite surface proteins (MSP- 119) and apical membrane antigen (AMA-1) was performed and the entomological inoculation rate (EIR) was estimated. To complement this information, retrospective data on treatment history, prescriptions by physicians and use of bed nets were collected. -

Risk, Overdiagnosis and Ethical Justifications

Health Care Analysis (2019) 27:231–248 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-019-00369-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Risk, Overdiagnosis and Ethical Justifcations Wendy A. Rogers1 · Vikki A. Entwistle2 · Stacy M. Carter3 Published online: 4 May 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Many healthcare practices expose people to risks of harmful outcomes. However, the major theories of moral philosophy struggle to assess whether, when and why it is ethically justifable to expose individuals to risks, as opposed to actually harming them. Sven Ove Hansson has proposed an approach to the ethical assessment of risk imposition that encourages attention to factors including questions of justice in the distribution of advantage and risk, people’s acceptance or otherwise of risks, and the scope individuals have to infuence the practices that generate risk. This paper investigates the ethical justifability of preventive healthcare practices that expose people to risks including overdiagnosis. We applied Hansson’s framework to three such practices: an ‘ideal’ breast screening service, a commercial personal genome testing service, and a guideline that lowers the diagnostic threshold for hypertension. The framework was challenging to apply, not least because healthcare has unclear boundaries and involves highly complex practices. Nonetheless, the framework encouraged attention to issues that would be widely recognised as morally pertinent. Our assessment supports the view that at least some preventive healthcare practices that impose risks including that of overdiagnosis are not ethically justifable. Further work is however needed to develop and/or test refned assessment criteria and guid‑ ance for applying them. Keywords Overdiagnosis · Risk · Uncertainty · Harm · Ethics · Risk evaluation * Wendy A. -

Diseases of Poverty and the 10/90 Gap Diseases of Poverty and the 10/90 Gap Diseases of Poverty and the 10/90 Gap

Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 gap Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 Gap Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 Gap Written by Philip Stevens, Director of Health Projects, International Policy Network November 2004 International Policy Network Third Floor, Bedford Chambers The Piazza London WC2E 8HA UK t : +4420 7836 0750 f: +4420 7836 0756 e: [email protected] w : www.policynetwork.net © International Policy Network 2004 Designed and typeset in Latin 725 by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Cover design by Sarah Hyndman Printed in Great Britain by Hanway Print Centre 102–106 Essex Road Islington N1 8LU All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 Gap Introduction: What is the 10/90 Gap? Figure 1 Number of daily deaths from diseases7 Activists claim that only 10 per cent of global health research is devoted to conditions that account for 90 Respiratory 10,814 per cent of the global disease burden – the so-called infections 1 ‘10/90 Gap’. They argue that virtually all diseases HIV/ 7,852 AIDS prevalent in low income countries are ‘neglected’ Diarrhoeal 5,482 and that the pharmaceutical industry has invested diseases almost nothing in research and development (R&D) Tuberculosis 4,504 for these diseases. -

Human Resource for Health Migration: an Analysis from the Perspective of Utilitarianism Rupesh Gautam University of Southern Denmark, [email protected]

Online Journal of Health Ethics Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 5 Human Resource for Health Migration: An Analysis from the Perspective of Utilitarianism Rupesh Gautam University of Southern Denmark, [email protected] Pawan Acharya University of Southern Denmark, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/ojhe Recommended Citation Gautam, R., & Acharya, P. (2016). Human Resource for Health Migration: An Analysis from the Perspective of Utilitarianism. Online Journal of Health Ethics, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.18785/ ojhe.1201.05 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Journal of Health Ethics by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Resource for Health Migration: An Analysis from the Perspective of Utilitarianism Introduction Medical brain drain or health-worker migration is a part of what has been labeled a global health workforce crisis and is characterized by the migration of trained and skilled health workers (doctors, nurses, and midwives) from low-income countries to high-income countries. It leads to loss in human capital for the developing countries, uneven distribution of those professionals between the affluent and poor countries and more severe suffering for the latter, due to the heavy disease burden (Kollar & Buyx, 2013; WHO, 2006). According to an estimate by WHO, a healthcare system is considered unable to deliver essential health services if it operates with fewer than 23 health workers (doctors, nurses, or midwives) for every 10,000 members of its population (WHO, 2006). -

Why Neglected Tropical Diseases Matter in Reducing Poverty 1.42 MB

July 2013 Working Paper 03 Why neglected tropical diseases matter in reducing poverty Fiona Samuels and Romina Rodríguez Pose • Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) have a direct impact on the achievement This and other Development of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Without addressing these Progress materials are available at Key diseases, the broader aim of poverty alleviation is unlikely to be achieved. developmentprogress.org messages • Straightforward and highly cost-effective strategies are available to control Development Progress is an ODI project and eventually eradicate or eliminate NTDs. that aims to measure, understand and communicate where and how progress • Success in controlling, eliminating or eradicating NTDs depends on has been made in development. partnerships between multiple constituencies that enable countries to adapt international guidelines to local contexts, integrate NTD programmes into ODI is the UK’s leading independent think tank on international development health systems and engage communities in implementation. and humanitarian issues. Further ODI materials are available at odi.org.uk Introduction indicators specific to them (Molyneux, 2008). While neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) One possible explanation for have been recognised for centuries – international disinterest is that NTDs indeed as ‘biblical plagues’ – NTDs have, almost exclusively affect the developing as the name implies, remained below the world (though this is also true for malaria) radar of most international and national and are not likely to spread far beyond; policy-makers. indeed, many NTDs have disappeared This relative neglect can be seen in completely in the developed world due examining the Millennium Development to improved hygiene and sanitation Goal (MDG) framework: while NTDs standards. -

Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery

x Chapter 1 Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery The beginning of 2020 ushered in a strong U.S. economy that was delivering job, income, and wealth gains to Americans of all backgrounds. By February 2020, the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.5 percent—the lowest in 50 years— and unemployment rates for minority groups and historically disadvantaged Americans were at or near their lowest points in recorded history. Wages were rising faster for workers than for managers, income and wealth inequality were on the decline, and median incomes for minority households were experienc- ing especially rapid gains. The fruits of this strong labor market expansion from 2017 to 2019 also included lifting 6.6 million people out of poverty, which is the largest three-year drop to start any presidency since the War on Poverty began in 1964. These accomplishments highlight the success of the Trump Administration’s pro-growth, pro-worker policies. The robust state of the U.S. economy in the three years through 2019 led almost all forecasters to expect continued healthy growth through 2020 and beyond. However, in late 2019 and the early months of 2020, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, with origins in the People’s Republic of China, began spreading around the globe and eventually within the United States, causing a pandemic and bringing with it an unprecedented economic and public health crisis. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy suffered sudden and massive shocks due to the pandemic. During the springtime lockdowns aimed at “flattening the curve,” the labor market lost 22.2 million jobs, and the unemployment rate jumped 11.2 percentage points, to 14.7 percent—the largest monthly changes in the series’ histories. -

COVID-19 & the Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why Did Sweden Not Lock

COVID-19 & The Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why did Sweden not lock down? What were they trying to achieve? Prathap Tharyan The world is cautiously trying to emerge from lockdowns People enjoying the sun in Stockholm on April 21, 2020 Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP via Getty images (Business Insider May 4 2020) No Lockdown: Do the Swedes know something the rest of the world does not know? Or are they playing “Russian Roulette” with their “Herd Immunity” strategy? SWEDEN’S RELAXED CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE NO LOCKDOWN IN SWEDEN: A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT IN COMBATING COVID-19 Cafes, bars, restaurants, elementary schools and most businesses, including hair salons and gyms are open and people are allowed to exercise outdoors Parks and public spaces are open Pubs and bars remain open https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/28/europe/sweden- Photograph: Ali Lorestani/EPA (The Guardian March 23) coronavirus-lockdown-strategy-intl/index.html WHY IS SWEDEN IS ‘DOING NOTHING’? Advice from the Public Health Agency Sweden has recommended good hygiene as part of infection control “Face masks are meant for Sweden’s Public Health Agency healthcare staff and not needed in in does not recommend face masks the community. for the public The best way to protect oneself and others in daily life is to maintain social distancing and good hand hygiene” SWEDISH PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY RECOMMENDS SOCIAL DISTANCING No large gatherings (50 people max.) Does not apply to schools, public transport, gyms Work from home if possible Keep arms-length distance from others in all public spaces including