Just Folks, Yarns and Legends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catálogo 2020 Haras San Pablo

CATÁLOGO 2020 HARAS SAN PABLO 1 PERÚ En la Carátula y en esta página: TOFFEE, alazana nacida el 16 de Julio del 2016, hija de WESTOW (USA) y LICHA LICHA (USA), por MR. GREELEY (USA). Defendiendo los colores del Stud Black Label y entrenada por Juan Suárez Villarroel, ganó el Clásico Enrique Ayulo Pardo (G1) (foto carátula), Roberto Álvarez Calderón (L), Iniciación (R), Selectos - Potrancas (R) y Ala Moana (foto arriba). POTRANCA CAMPEONA DE 2 AÑOS y POTRANCA CAMPEONA DE 3 AÑOS el 2019 HARAS SAN PABLO (Fundado en 1979) PRODUCTOS FINA SANGRE DE CARRERA NACIDOS EN EL SEGUNDO SEMESTRE DE 2018 HIJOS DE: FLANDERS FIELDS (USA) KOKO MAMBO (PER-G1) MAN OF IRON (USA) MINISTER’S JOY (USA) YAZAMAAN (GB) Irrigación Santa Rosa Sayán - Lima, Perú 2020 INDICE Instrucciones para el uso de este catálogo ..................................................................................7 Plantel de Reproductores del Haras San Pablo - Padrillos y Yeguas Madres .....................12 Caballos CAMPEONES criados en el Haras San Pablo ..........................................................16 Clásicos GRUPO UNO, GRUPO DOS, GRUPO TRES ganados por el Haras San Pablo ..17 Productos ganadores de los Clásicos Selectos y Copa Criadores de la Asociación de Criadores de Caballos de Carrera del Perú ..............................................................................21 PADRILLOS EDITORIAL (USA), por War Front en Playa Maya por Arch ...............................................24 FLANDERS FIELDS (USA), por A.P. Indy en Flanders por Seeking the Gold .................28 KOKO MAMBO (PER), por Apprentice en Not For Sale por Mashhor Dancer ...............32 MAN OF IRON (USA), por Giant´s Causeway en Better Than Honour por Deputy Minister ...........36 MINISTER’S JOY (USA), por Deputy Minister en Meghan’s Joy por A.P. -

The Collegian Special Collections and Archives

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV The Collegian Special Collections and Archives 9-1-2008 The Collegian (2008-09-01) Isis Lopez The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/collegian Recommended Citation The Collegian (BLIBR-0075). UTRGV Digital Library, The University of Texas – Rio Grande Valley This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Collegian by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE STUDENT VOICE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT BROWNSVILLE AND TEXAS SOUTHMOST COLLEGE THE Volume 61 Monday OLLEGIANwww.collegian.utb.edu CIssue 3 September 1, 2008 STEADY AIM Campus’ tab for Dolly: $1M By David Boon is something that we planned to Staff Writer do. ... We didn’t need Dolly to tell us that, we knew we were going to Hurricane Dolly cost the do that. But Dolly kind of pushed university more than $1 million, us along a little bit.” officials say. The Education and Business This figure includes money that Complex’s cooling unit, known is being spent on preventative as a “chiller,” and the campus maintenance to avoid further windows, specifically in Tandy damage to the buildings should Hall, sustained major damage there ever be a similar event. during the hurricane, which struck “If you add up everything, the Rio Grande Valley on July 23. [it] would be over a million,” “A chiller is an air-conditioning said Alan Peakes, assistant vice unit which cools the water, which president of Facilities Services. -

![Legends of Saint Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4501/legends-of-saint-joseph-patron-of-the-universal-church-microform-1114501.webp)

Legends of Saint Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church [Microform]

/ / *C^ #? ^ ////, A/ i/.A IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) 1.0 IB %. ^ !E U£ 112.0 I.I 1.8 1.25 U 11.6 # \ SV \\ V ^^J'V^ % O^ o> Photographic €^ 23 WEST MAIN STREET WEBSTER, N.Y. 14580 Sciences (716) 872-4503 Corporation ^*... "•"^te- «iS5*SSEi^g^!^5«i; 'it^, '<^ t& CIHM/ICMH CIHM/ICMH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions / Institut Canadian de microreproductions historiques S ^ <; jv. - s»«5as^a«fe*Sia8B®I6jse»a!^«i)^w«*«i*asis»swp£>9^^ '*s* - ' 1 _ ssfijr Technical and Bibliographic Notes/Notes techniques et bibliographiques microfilm^ le meilleur exemplaire The Institute has attempted to obtain the best L'Institut a se procurer. Les d6tails original copy available for filming. Features of this qu'il lui a 6t6 possible de uniques du copy which may be bibliographically unique, de cet exemplaire qui sont peut-Atre bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier which may alter any of the images in the point de vue peuvent exiger unc reproduction, or which may significantly change une image reproduite, ou qui normale de filmage the usual method of filming, are checked below. modification dans la m6thode sont indiqu^s ci-dessous. Coloured covers/ Coloured pages/ D Couverture de couleur Pages de couleur Covers damaged/ Pages damaged/ D Couverture endommag^e Pages endommagdes Covers restored and/or laminated/ Pages restored and/or laminated/ D Couverture restaur6e et/ou pellicul6e Pages restaur6es et/ou pellicul6es stained or foxed/ Cover title missing/ Pages discoloured, tachetdes ou piqu6es Le titre de couverture manque Pages d6color6es, Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ D Cartes g6ographiques en couleur Pages ddtach^es Coloured ink (i.e. -

THOROUGHBRE'ntm -L D®A®I®L®Y N•E^W^S ^ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 1998 $2 Daily

the Thoroughbred Daily News is delivered to your fax each morning by 5 a.m. For subscription information, please call (732) 747-8060. THOROUGHBRE'nTM -L D®A®I®L®Y N•E^W^S ^ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 1998 $2 Daily N • E • w • S K*e*e*n*e*l*a*n*D TODAY RESULTS STUD FEE SET FOR SKIP AWAY Rick Trontz's SUN BLUSH TOPS KEENELAND TUESDAY Selling Hopewell Farm in Lexington, Kentucky has set the 1999 as hip number 3295, the nine-year-old mare Sun Blush stud fee for Horse of the Year candidate Skip Away (Ogygian-lmmense, by Roberto), in foal to Boone's Mill (Skip Trial) at $50,000 live foal. "We think it's a great (Carson City), brought $290,000 to top yesterday's value for a horse like Skip Away," said Trontz. "We've session of the Keeneland November Breeding Stock had an excellent response from breeders and look for Sale. Phil T. Owens, agent, bought the half-sister to ward to an outstanding book of mares." The Champion multiple graded stakes-winner Mariah's Storm (Rahy) Three-Year-Old Colt of 1996 and Champion Older Horse from the consignment of John Williams, agent. Sun of 1997, Skip Away retired with 18 wins and earnings Blush is the dam of the stakes winning three-year-old of $9,616,360. filly Relinquish (Rahy). Hip number 3394, a bay colt by Supremo~By Four Thirty (Proudest Roman), was bought CARTIER AWARDS ANNOUNCED The Cartier for $73,000 by John Oxiey to bring the top weanling Awards, the first in a number of competing awards price of the session. -

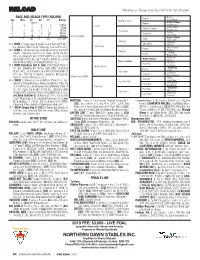

RELOAD 2009 Chestnut - Dosage Profile: 13-7-19-1-0; DI: 2.81; CD: +0.80

RELOAD 2009 Chestnut - Dosage Profile: 13-7-19-1-0; DI: 2.81; CD: +0.80 Nearco RACE AND (BLACK-TYPE) RECORD Nearctic *Lady Angela Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earnings Northern Dancer Native Dancer 2 n uraced Natalma Almahmoud 3 8 1 4 1 1 1 2 ,$250 Danzig Crafty Admiral 4 7 2 0 0 5 , 6 5 94 Admiral’s Voyage Olympia Lou 5 2 ( 12) 0 0 1 91,100 Pas de Nom Petition 6 5 2 0 ( 2 )2 135,500 *Petitioner Steady Aim Hard Spun (2004) 7 2 ( 1) 0 0 0 51,000 Raise a Native Alydar 42 8(2) 4 3 (2) $ 567,504 Sweet Tooth Turkoman Table Play Taba (ARG) At 3, WON a maiden special weight race at Belmont Park (7 Filipina Turkish Tryst fur., defeating Wild Target, Stressing, Love to Run, etc.). Hail to Reason Roberto Bramalea At 4, WON an allowance race at Keeneland (6 fur., by 6 3/4 Darbyvail *My Babu lengths, defeating Casino Dan, Seve, Grand Coulee, Luiana Banquet Bell Reload etc.), an allowance race at Belmont Park (7 fur., equal Polynesian Native Dancer top weight of 122 lbs., by 5 lengths, defeating Escrow Geisha Raise a Native Kid, Inflation Target, Schoolyard Dreams, etc.). Case Ace Raise You Lady Glory At 5, WON Canadian Turf S. [G3] at Gulfstream Park (1 Mr. Prospector *Nasrullah mi., turf, defeating Mr. Online, Salto (IRE), Unbridled Nashua Segula Gold Digger Ocean, etc.), an allowance race at Gulfstream Park (1 Count Fleet Sequence 1/16 mi., turf, by 3 lengths, defeating Bombaguia, Miss Dogwood Hidden Reserve (1994) Kalamos, English Progress, etc.). -

2019 Mid-Atlantic Stallion Directory Pedigree Page Explanations

2019 Mid-Atlantic Stallion Directory Pedigree page explanations ncluded in this section are pedigrees and In Male Lines and Stud Records, progeny have their points split between the two apti- pertinent data on 65 Thoroughbred stal- are arranged in order by champions, Grade 1 tudes. In the end, the total points in each col- Ilions standing at stud in the Mid-Atlantic winners then stakes winners by earnings. umn produce the Dosage Profile, a series of region. NOTICE: The eligibility status of stal- five numbers which reflect the relative pro- Statistics are accurate at least through lions nominated to national or state breed- portions of each of the five aptitudes in this Nov. 4, 2018. Statistics, as furnished by The ers’ programs (Breeders’ Cup, Maryland order: Brilliant-Intermediate-Classic-Solid- Jockey Club Information Systems, Blood- Million, etc.) is dependent on the nomina- Professional. stock Research Inc., Equibase and/or Daily tors’ compliance with conditions, rules and Racing Form, include results from North regulations of those programs. Mid-Atlantic “The ratio of points in the speed wing 1 America, England, Ireland, France, Italy and Thoroughbred cannot assume responsibility (Brilliant points + Intermediate points + ⁄2 Japan. Foreign statistics for countries other for nominators’ compliance with these regu- the Classic points) to points in the stamina 1 than England, Ireland, France, Italy and Ja- lations. Mare owners are advised to confirm wing ( ⁄2 the Classic points + Solid points + pan are included when available. eligibility with the stallion owners. Professional points) is the Dosage Index. (Dividing the stamina points into the speed The Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred has ad- DOSAGE opted the following criteria for stakes quali- points.) This number is directly proportional Dosage is explained as follows by Dr. -

A Study in Scarlet

A Study In Scarlet Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. Table of contents Part I Mr. Sherlock Holmes . 5 The Science Of Deduction . 8 The Lauriston Garden Mystery . 12 What John Rance Had To Tell. 17 Our Advertisement Brings A Visitor . 20 Tobias Gregson Shows What He Can Do. 23 Light In The Darkness . 27 Part II On The Great Alkali Plain . 35 The Flower Of Utah . 39 John Ferrier Talks With The Prophet . 42 A Flight For Life . 44 The Avenging Angels . 48 A Continuation Of The Reminiscences Of John Watson, M.D. 52 The Conclusion . 57 1 PART I. (Being a reprint from the reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D., late of the Army Medical Department.) CHAPTER I. Mr.Sherlock Holmes n the year 1878 I took my degree of irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time at Doctor of Medicine of the University of a private hotel in the Strand, leading a comfortless, London, and proceeded to Netley to go meaningless existence, and spending such money I through the course prescribed for sur- as I had, considerably more freely than I ought. -

The Life and Times of Philip Schuyler

C ITAPTER XXVII. W H I LE General Schuyler was engaged, during the c1osing decade of the last century, in warm political strife, he was bnsily employed in labors for the promotion of great pnhi ic "·orks, c:alcu lated to develop the resources of his natfre State, and improve and aggrandize H. li'or him may be justly claimed, I think, the honor of the pater nity of the canal system in the State of N cw York, which for long years formed an essential element in its prosper ity; for, as we have seen, he talked to Charles Carroll upon the subject so early as the spring of 1776, and had entered into a calculation of the actual cost of a canal that should connect the Hudson Ri.. er "·ith Lake Chamvlain, as has since been done.* T hat honor has been rlaimed for Elkanah "\Vatson, 'Christopher Colles and others, but I have nowhere seen any record of a proposition to constrnct snch a work in this country, so early, by several years, as that of General Schuyler, mentioned by Carroll.t * See pag~ 40,of this Yo]ume. t In 1820, Mr. Watson, in a" Summary History of the Riso, Pro gr<'es, and Existing Stnte of the Grand [EriE>] Canal, with Rcmnrks," alJuding to rival claims to the pnternity of the canal policy, snys: "It is altogether probable that General Schuyler's enlarged and C'Otnpr(>hensh·e mind may have conceh·cd such n project nt an eul'ly day, although I haYe not been able to trace- any fact lc:a<ling to suc-h a disclosure; at least, not until he promulgated thP canal-law, in 17!>2. -

Alien Odyssey

Email me with your comments! To my wife Donna, Daughters Jennifer and Kerri, Son Matthew, and Seven Grandchildren. Thanks for your inspiration and support! Table of Contents (Click on Title) The Aliens (List of Characters) ii Chapter One: The Third Planet 1 Chapter Two: Forbidden Garden 6 Chapter Three: Doctor Arkru’s Plan 17 Chapter Four: Alien Safari 29 Chapter Five: Aboard The Ark 46 Chapter Six: The Collection Teams 66 Chapter Seven: Rifkin To The Rescue 93 Chapter Eight: Somewhere In The Forest 104 Chapter Nine: The Rescue Teams 115 Chapter Ten: The Rifkin Madness 122 Chapter Eleven: Disaster In The Forest 133 Chapter Twelve: The Adventures Of Rifkin 149 Chapter Thirteen: Disaster Strikes Again 161 Chapter Fourteen: The Rescue Of Rifkin 168 Epilogue: Written In The Rocks 185 Glossary Revekian Terms & Concepts 188 Poem Rifkin’s Ballad 195 ii The Aliens The Leaders Doctor Arkru (the Professor) Chief scientist of the Ark, whose good intentions for the student collectors are based upon the friendlier worlds of Beskol, Raethia, and Orm. Falon Commander of the vessel, who discovers the new planet, but remains Arkru’s staunchest critic after landing on the new world. The Students Rifkin Prodigal student, whose reckless personality leads to disaster on the planet. Zither Intellectual member of Arkru’s class, whose personal odyssey becomes a central theme. Rezwit Kindred spirit of Rifkin, a favorite of the professor, until mayhem breaks in the forest. Vimml Fun loving but mischievous follower of Rifkin, who creates havoc on and off the ship. Shizwit Shy student, who, rising to the crisis, becomes the Key Master of her class. -

Short Story Unit English 2201

Short Story Unit English 2201 The Necklace- Guy de Maupassant Short story found on page 322 Focus on: Symbolism - An object used to represent a more complex, abstract idea. Situational Irony - The result is opposite of what was expected. Theme - The intended message of a piece of literature. 1. The necklace is the main symbol in the story. Explain what it represents and how the symbol leads to situational irony. ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ -

Martes 20 De Marzo Muestra Y Almuerzo: 12Hs / Remate: 14Hs Tattersall Del Hipódromo De San Isidro Ídolo Porteño Jump Start En Idealidad (Roy)

la esperanza_tapa madres.pdf 1 15/2/18 8:19 a.m. Yeguas ganadoras clásicas como FIEREZE (G2) · NOMINADORA (G2) · SPICE GIRL (G2) LISTADA (G3) · TRINCHETA (G3) · ECLISA (L) · GRANDERA (L) PERVERSA (L) · FIESTA DORADA · CUT PARADE · ICY LAKE FIESTA SUREÑA · SEXOLOGIA Y OTRAS Madres de ganadores clásicos como FIESTA LADY (CAMPEONA 3 AÑOS, G1) SEXY REASONS (G1) · EJECUTOR (G1) · TRANSONICO (G2) FARUSCHENKO (G2) · PERVERSADO (G2) · ESTRECHADA (G3) EXCHANGER (G3) · ICEBOX (G3) · THUNDER DOVE (L) CUT START (L) · PREACHING · FIESTA DORADA TRINCHETO · INALTERANCIA · PROMOVEDORA FIESTA SUREÑA Y OTROS Yeguas madre por ROY HONOUR AND GLORY CANDY STRIPES DANZIG FITZCARRALDO EXCHANGE RATE INTERPRETE THUNDER GULCH SALT LAKE PULPIT CONFIDENTIAL TALK SEEKING THE GOLD JUMP START WOODMAN KITWOOD DIXIELAND BAND NOT FOR SALE ENTRE OTROS PURE PRIZE Servidas por E DUBAI SEEK AGAIN PORTAL DEL ALTO SUGGESTIVE BOY TRUE CAUSE Stud 9 · Diego Carman 222 Oficina: Blanco Encalada 197 - 0f. 50 (1642) San Isidro Buenos Aires (1642) San Isidro, Buenos Aires (54-11)-4735-4755 (54-11)-4735-0457/58 www.fallowremates.com Haras: RN 8 - Km 119 [email protected] San Antonio de Areco, Buenos Aires [email protected] Martes 20 de marzo Muestra y almuerzo: 12hs / Remate: 14hs Tattersall del Hipódromo de San Isidro Ídolo Porteño Jump Start en Idealidad (Roy) CABALLO DEL AÑO / MEJOR CABALLO ADULTO / MEJOR FONDISTA GRAN PREMIO INTERNACIONAL CARLOS PELLEGRINI [(G1)[ GRAN PREMIO INTERNACIONAL DARDO ROCHA [(G1) CAMPEONA 3 AÑOS HEMBRA GRAN PREMIO SELECCION [(G1)[ CLASICO FRANCISCO J. BEAZLEY [(G2)[ Fiesta Southern Halo Lady en Fiereze (Political Ambition) ALGUNAS DESTACADAS Familia 7 Bambuca FAMILIAS DEL HARAS 39 - LA BALANDRA, por Jump Start y La Baraca, por Mariache. -

247 Development 2016 1 Pen Y Banc Seven Sisters Neath

2020 Catalogue 247 Development 2016 1 Pen Y Banc Seven Sisters Neath SA10 9AB 01639 701583 Copyright January 2020 £2.00 Payment details If you intend paying by Cheque Please use the open Cheque Method. If your Order is for £10.00 & £1.15 postage & packing, You would endorse your Cheque as “Not More than say £15.00. This margin will allow for any price increase or error in the calculations. We will complete the cheque to the value of the order. A detailed invoice is always included with your order Credit & Debit Card Facilities are available by Phone or by sending the info in more than One E-mail 60p surcharge on orders less than £10.00 Post & Packing UK Addresses Due to the complexities of Royal Mails prices it’s Difficult to quote for mixed orders as a Rough Gide here are some Examples; Orders up to 100 grams packed in a padded mail lite bag £1.25 1st class & £2.45 1st class Recorded Orders up to 250 grams packed in a padded mail lite bag £1.70 1st class & £2.90 1st class Recorded Small Parcells; £3.75/ recorded £4.75 up to 1kg Proof of posting is Acquired for all orders sent out Page 2 Prices GWR Name plates £7.00 a set unless stated next to the listing. If you need the GWR Name plate finished in RED the Plates will cost £3.00 Extra GWR Cab side plates £5.50 If you need the GWR Cab Side plate finished in RED the Plates will cost £1.50 Extra SR Name Plates £6.50 a set Unless stated in the listing SR Smokebox Numbers £2.20 LMS/MR Name Plates £6.50 a set Unless stated in the listing LMS/MR Smokebox Numbers £2.20 LNER/ER Name Plates £6.50