Master Thesis with Concentration I N Film and Audiovisu Al Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharin Foo Manuskript: Sławomir Mroźek Scenograf: Karin Trille Høy Om Vejen Til Toppen – Og Turen Ned Igen BETTY NANSEN Teatrets Anneksscene 7

ARKITEKTUR KULTUR BYLIV DESIGN AKTIVITETER MAGASINET DESIGN Lyd i keramikhornet – men helt uden strøm? TOP+FLOP Johan Wohlert Død over neonfarver og lysstofrør SHOPPING Sofaer Slap nu af UPDATE Fire nye broer NR 48 · NOVEMBER 2009 · GRATIS Nu bliver Holmen en del af byen BY GRØNT Velkommen MINITEMA TIL CO2PIA KLIMA-KØBENHAVN FYLDES MED ELBILER, VINDVENDERE OG GRØNNE TAGTOppE KULTUR HVOR UFORSKAMMET UHØFLIGE KØBENHAVN GIVER DIG FINGEREN BYLIV LUGTER ENGHAVE ALTID AF PIS? PÅ TUR MED DSB OG EN SNAKKENDE IPOD emigranterne PORTRÆT om hjemvé, håb og hundemad Thomas Bo Larsen & Tom Jensen Instruktion: Peter Langdal Sharin Foo Manuskript: Sławomir Mroźek Scenograf: Karin Trille Høy OM VEJEN TIL TOppEN – OG TUREN NED IGEN BETTY NANSEN TEATRETs anneksscene 7. november - 12. december ma–fre kl. 20, lø kl. 17. Tlf. 33 21 14 90 www.bettynansen.dk [HPLJUDQWLQGG L Ê JAPANSK LUKSUS Makiruller m. laks, SUNDT & L råmarinerede laks, dampede Ê tigerrejer, krabbesalat. SYNDIGT KINESISKE PAKKER Brioche m. barbecuesvinekød, riskager m. rejer og kokosmælk, dimsum m. rejer, wontons, vietnamesiske forårsruller og BRUNCH kyllingespyd. TRADITIONEN TRO Bacon, cocktailpølser, røræg, BUFFET jalapenos, røget skinke, tomatsalat, kyllingesalat LØRDAG/SØNDAG og oste. FRISTENDE 10.00 - 15.00 DESSERTER Chokolade fondue, frisk VESTERBROGADE 40 frugt, marshmellows, DK-1620 KBH. V. LELE-NHAHANG.COM pandekager, yoghurt m. bær, 155 kr. TELEFON 3322 7135 mini wienerbrød. LêLê nhà hàng INDHOLD NR 48 · NOVEMBER 2009 « BY CO2PIA 14 Du kan lige så godt vænne dig til vindmøller, elbiler, grønne tagtoppe og klimaopdragelse. I 2025 skal København nemlig være verdens første CO2-neutrale hovedstad. PORTRÆT SHARIN FOO 26 Hun voksede op i en kinesisk landsby og i en københavnerkoloni i Jylland. -

16: the Up-And-Coming Metro Phoenix Bands to Watch This Year

1/28/2016 16 Metro Phoenix Bands to Watch in 2016 | Phoenix New Times 16 FOR '16: THE UP-AND-COMING METRO PHOENIX BANDS TO WATCH THIS YEAR BY AMY YOUNG, LAUREN WISE, JARON IKNER, TOM REARDON, JEFF MOSES, ROGER CALAMAIO, GARYN KLASEK, SERENE DOMINIC, JASON KEIL, JASON P. WOODBURY, MITCHELL HILLMAN WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 27, 2016 | 1 DAY AGO Couples Fight Jim Louvau The new year means new beginnings, fresh ideas, and more chances to give birth to new projects. In such a populous area, we are privy to a tremendous amount of ambition and diversity when it comes to the local music scene. The area's creative class constantly churns out new music. The city overflows with talent, from bands with members not old enough to drink to veterans with decades of music experience in the scene. With that in mind, we present to you 16 promising local bands to watch in 2016. These bands span a range of genres, from noisy punk to electro pop to surf-tinged garage rock, but they all share a common drive to create great music and share it with the world. Don't be surprised to see these bands popping up on lineups at venues around town and filling out the local slots once festival season hits. Give these bands a listen. We don't think you'll be disappointed. http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/music/16for16theupandcomingmetrophoenixbandstowatchthisyear8001905 1/10 1/28/2016 16 Metro Phoenix Bands to Watch in 2016 | Phoenix New Times Molly and the Molluscs Dani Perez Molly and the Molluscs These band members are having a better time than you. -

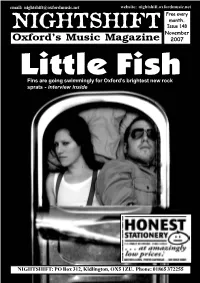

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Lab Data.Pages

Day 1 The Smiths Alternative Rock 1 6:48 Death Day Dark Wave 1 4:56 The KVB Dark Wave 1 4:11 Suuns Dark Wave 6 35:00 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 2 8:09 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:43 HTRK Indie Rock 9 40:35 TV On The Radio Indie Rock 1 3:26 Warpaint Indie Rock 19 110:47 Joy Division Post-Punk 1 3:54 Lebanon Hanover Post-Punk 1 4:53 My Bloody Valentine Post-Punk 1 6:59 The Soft Moon Post-Punk 1 3:14 Sonic Youth Post-Punk 1 4:08 18+ R&B 6 21:46 Massive Attack Trip Hop 2 11:41 Trip-Hop 11:41 Indie Rock 158:31 R&B 21:46 Post-Punk 22:15 Dark Wave 52:16 Alternative Rock 6:48 Day 2 Blonde Redhead Alternative Rock 1 5:19 Mazzy Star Alternative Rock 1 4:51 Pixies Alternative Rock 1 3:31 Radiohead Alternative Rock 1 3:54 The Smashing Alternative Rock 1 4:26 Pumpkins The Stone Roses Alternative Rock 1 4:53 Alabama Shakes Blues Rock 3 12:05 Suuns Dark Wave 2 9:37 Tropic of Cancer Dark Wave 1 3:48 Com Truise Electronic 2 7:29 Les Sins Electronic 1 5:18 A Tribe Called Quest Hip Hop 1 4:04 Best Coast Indie Pop 1 2:07 The Drums Indie Pop 2 6:48 Future Islands Indie Pop 1 3:46 The Go! Team Indie Pop 1 4:15 Mr Twin Sister Indie Pop 3 12:27 Toro y Moi Indie Pop 1 2:28 Twin Sister Indie Pop 2 7:21 Washed Out Indie Pop 1 3:15 The xx Indie Pop 1 2:57 Blood Orange Indie Rock 6 27:34 Cherry Glazerr Indie Rock 6 21:14 Deerhunter Indie Rock 2 11:42 Destroyer Indie Rock 1 6:18 DIIV Indie Rock 1 3:33 Kurt Vile Indie Rock 1 6:19 Real Estate Indie Rock 2 10:38 The Soft Pack Indie Rock 1 3:52 Warpaint Indie Rock 1 4:45 The Jesus and Mary Post-Punk 1 3:02 Chain Joy Division Post-Punk -

You Wanted Columns? You Got 'Em>>

FOR FANS OF MUSIC & THOSE WHO MAKE IT Issue 10 • FREE • athensblur.com THESE UNITED STATES • MAD WHISKEY GRIN • BLITZEN TRAPPER • THE DELFIELDS • MEIKO • JANELLE MONAE • TRANCES ARC • DODD FERRELLE • CRACKER & MORE!!! ZERO 7 Acclaimed electronic duo gets haunted on album number four TORTOISE Inspiration be damned — Tortoise soldiers on WHEN You’rE HOT Bradley Cooper’s sizzling Hollywood ride HEART LIFE AT THE SPEED IN haND OF TWEET The latest social media After an eight-year absence, an outlet is changing the music industry, for energized Circulatory System better or for worse returns with a new album VENUE VENTURES Four clubs lead the way into a changing face of Athens music spots YOU WANTED COLUMNS? YOU GOt ‘eM>> SIGN UP AT www.gamey.com/print ENTER CODE: NEWS65 *New members only. Free trial valid in the 50 United States only, and cannot be combined with any other offer. Limit one per household. First-time customers only. Internet access and valid payment method required to redeem offer. GameFly will begin to bill your payment method for the plan selected at sign-up at the completion of the free trial unless you cancel prior to the end of the free trial. Plan prices subject to change. Please visit www.gamey.com/terms for complete Terms of Use. Free Trial Offer expires 12/31/2010. (44) After an eight-year absence, an energized Circulatory System returns with a new HEART album. by Ed Morales IN HAND photos by Jason Thrasher (40) (48) Acclaimed electronic duo Zero 7 gets “haunted” The latest social making album number media outlet is four. -

Mechanical Properties and Durability of Polypropylene and Steel Fiber-Reinforced Recycled Aggregates Concrete (FRRAC): a Review

sustainability Review Mechanical Properties and Durability of Polypropylene and Steel Fiber-Reinforced Recycled Aggregates Concrete (FRRAC): A Review Peng Zhang 1 , Yonghui Yang 1, Juan Wang 1,*, Shaowei Hu 1,2, Meiju Jiao 1 and Yifeng Ling 3 1 School of Water Conservancy Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China; [email protected] (P.Z.); [email protected] (Y.Y.); [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (M.J.) 2 College of Civil Engineering, Chongqing University, Chongqing 400045, China 3 Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 October 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 15 November 2020 Abstract: With the development of concrete engineering, a large amount of construction, demolition, excavation waste (CDEW) has been produced. The treated CDEW can be used as recycled aggregate to replace natural aggregate, which can not only reduce environmental pollution and construction-related resource waste caused by CDEW, but also save natural resources. However, the mechanical properties and durability of Recycled Aggregates Concrete (RAC) are generally worse than that of ordinary concrete. Various fiber or mineral materials are usually used in RAC to improve the mechanical properties and durability of the matrix. In RAC, polypropylene (PP) fiber and steel fiber (SF) are two kinds most commonly used fiber materials, which can enhance the strength and toughness of RAC and compensate the defects of RAC to some extent. In this paper, the literature on PP fiber- and SF-reinforced RAC (FRRAC) is reviewed, with a focus on the consistence, mechanical performance (compressive strength, tensile strength, stress–strain relationship, elastic modulus, and shear strength), durability (water absorption, chloride permeability, carbonation, freeze–thaw cycling, and shrinkage), and microstructure. -

Lana Del Rey - Born to Die: the Paradise Edition Pdf

FREE LANA DEL REY - BORN TO DIE: THE PARADISE EDITION PDF Lana Del Rey | 136 pages | 01 Mar 2013 | Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 9781458448620 | English | United States Born to Die - Paradise Edition - Rolling Stone Paradise is the third extended play and second major release by American singer and songwriter Lana Del Rey ; it was released on November 9, by Universal Music. It was additionally packaged with the reissue of her second studio albumBorn to Dietitled Born to Die: The Paradise Edition. The EP's sound has been described as baroque pop [1] and trip hop. Upon its release, Paradise received generally favorable reviews from music critics. The extended play debuted at No. It also debuted at No. That same month, an EP of the same name was made available for digital purchase, containing the film along with the three aforementioned songs. In an interview with RTVE on June 15,Del Rey announced that she had Lana del Rey - Born to Die: The Paradise Edition working on a new album due in November, and that five tracks had already been written, [3] two of them being " Young and Beautiful " [ citation needed ] and "Gods and Monsters", [ citation needed ] and another track titled "Body Electric", which was performed and announced as one of her songs at BBC Radio 1's Hackney Weekend. The prior album's re-release, titled Born to Die: The Paradise Editionwas available for pre-order offering an immediate download of "Burning Desire" in some countries. The song served as the soundtrack for a short film called Desire[8] directed by Ridley Scott and starring Damian Lewis. -

“All Politicians Are Crooks and Liars”

Blur EXCLUSIVE Alex James on Cameron, Damon & the next album 2 MAY 2015 2 MAY Is protest music dead? Noel Gallagher Enter Shikari Savages “All politicians are Matt Bellamy crooks and liars” The Horrors HAVE THEIR SAY The GEORGE W BUSH W GEORGE Prodigy + Speedy Ortiz STILL STARTING FIRES A$AP Rocky Django Django “They misunderestimated me” David Byrne THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE OF MUSIC Palma Violets 2 MAY 2015 | £2.50 US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 # "% # %$ % & "" " "$ % %"&# " # " %% " "& ### " "& "$# " " % & " " &# ! " % & "% % BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 2 MAY 2015 Anna B Savage 23 Matthew E White 51 A$AP Rocky 10 Mogwai 35 Best Coast 43 Muse 33 REGULARS The Big Moon 22 Naked 23 FEATURES Black Rebel Motorcycle Nicky Blitz 24 Club 17 Noel Gallagher 33 4 Blanck Mass 44 Oasis 13 SOUNDING OFF Blur 36 Paddy Hanna 25 6 26 Breeze 25 Palma Violets 34, 42 ON REPEAT The Prodigy Brian Wilson 43 Patrick Watson 43 Braintree’s baddest give us both The Britanys 24 Passion Pit 43 16 IN THE STUDIO Broadbay 23 Pink Teens 24 Radkey barrels on politics, heritage acts and Caribou 33 The Prodigy 26 the terrible state of modern dance Carl Barât & The Jackals 48 Radkey 16 17 ANATOMY music. Oh, and eco light bulbs… Chastity Belt 45 Refused 6, 13 Coneheads 23 Remi Kabaka 15 David Byrne 12 Ride 21 OF AN ALBUM De La Soul 7 Rihanna 6 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club 32 Protest music Django Django 15, 44 Rolo Tomassi 6 – ‘BRMC’ Drenge 33 Rozi Plain 24 On the eve of the general election, we Du Blonde 35 Run The Jewels 6 -

Africa in the Media

January 2019 By Johanna Blakley, Adam Amel Rogers, Erica Watson-Currie and Kristin (Eun Jung) Jung TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS 6 TELEVISION FINDINGS 6 TWITTER FINDINGS 7 CROSSCUTTING FINDINGS 8 AFRICA ON TELEVISION 9 NUMBER OF MENTIONS 9 TYPES OF MENTIONS 10 AFRICA IN SCRIPTED ENTERTAINMENT 12 TYPES OF ENTERTAINMENT DEPICTIONS 12 SENTIMENT OF DEPICTIONS 14 AFRICAN CHARACTERS AND PERSONALITIES 23 AFRICA ON TWITTER 26 VOLUME OF TWEETS 27 SENTIMENT TOWARD AFRICA 28 BLACK PANTHER ON TV AND TWITTER 37 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 42 METHODOLOGY 45 APPENDIX 48 ABOUT US 51 AFRICA NARRATIVE | USC LEAR CENTER Africa in the Media INTRODUCTION THE AFRICA NARRATIVE, WHICH IS BASED AT THE that provide a counterpoint showing the success, diversity, Norman Lear Center at the USC Annenberg School for Com- opportunity and vibrancy of Africa — its emerging middle munication and Journalism, was established to create great- class; technology and innovation; solutions-driven culture; er public knowledge and understanding of and engagement growing economies and democracies; and talent in the ar- with Africa through research, creative communications cam- eas of the arts and entertainment, technology, business and paigns and collaborations with private, public and non-profit government. partners. Even when the coverage of Africa was, on its surface, posi- Recognizing the pivotal role of media and entertainment in tive, it was described as often glib, simplistic, predictable, shaping perceptions and opinions of Africa and African peo- and sometimes sensationalist or extreme, at the expense of ple, Africa in the Media is the Africa Narrative’s inaugural re- showcasing regular voices and stories of Africa. -

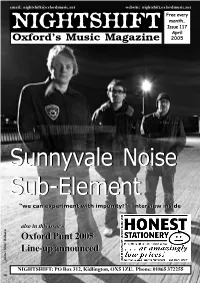

Issue 117.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 117 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SunnyvaleSunnyvale NoiseNoise Sub-ElementSub-Element “we“we cancan experimentexperiment withwith impunity!”impunity!” -- interviewinterview insideinside alsoalso inin thisthis issueissue -- OxfordOxford PuntPunt 20052005 Line-upLine-up announcedannounced photo: Miles Walkden photo: Miles NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE LINE-UP FOR THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT HAS BEEN finalised. The Punt takes place on Wednesay 11th May and features 24 local bands and solo artists playing across eight venues on one night. The Punt is now established as the best showcase of local unsigned music. This year Nightshift received over 100 demos from local acts hoping to take part. The Punt received an added boost last month when Kiss Bar became the eighth venue to be added to the event, meaning we could fit an extra three bands on the bill, making this the biggest Punt ever. The full line up is as follows: Borders: 6.15pm: Laima Bite; 7pm: Kate Chadwick. Jongleurs: 7.30: The Evenings; 8.15: A Silent Film; 9pm: The Factory THE YOUNG KNIVES release a new EP on May 16th on hot new indie Far From The Madding Crowd (in conjunction with Delicious Music): label Transgressive, the label that launched The Subways earlier this 8.15: Zoe Bicat; 9.15: The Thumb Quintet; 10.15: Chantelle Pike. year. Tracks on the limited 10” EP are ‘Coastgard’, ‘Kramer Vs The City Tavern: 8.30: The Half Rabbits; 9.30: Fell City Girl; 10.30: Kramer’, ‘Weekends And Bleak days’ and ‘Trembling Of The Trails’, all Junkie Brush. -

The Influence of Network Design on Firm Performance – Perspectives and Empirical Evidence

THE INFLUENCE OF NETWORK DESIGN ON FIRM PERFORMANCE – PERSPECTIVES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften durch die Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster WESTFÄLISCHE WILHELMS-UNIVERSITÄT MÜNSTER vorgelegt von BRINJA MEISEBERG aus Bottrop Münster, 2010 Erster Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Thomas Ehrmann Zweite Berichterstatterin: Prof. Dr. Anja Tuschke Dekan: Prof. Dr. Stefan Klein Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 12. April 2010 Acknowledgements The process of writing this dissertation was accompanied by a number of people to whom I would like to express my gratitude for their support. I am sincerely indebted to my dissertation advisor, Prof. Dr. Thomas Ehrmann, Institute of Stra- tegic Management at Münster University, for his guidance and promotion of my research efforts, and for providing extensive expertise and creative commentary whenever needed. I am also in- debted for his continuous trust in taking me on as a research assistant. I thank Prof. Dr. Anja Tuschke, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, for her co-supervisory of my dissertation. I extend my thanks to Prof. Dr. Martin Bohl and Prof. Dr. Gerhard Schewe, both of Münster University, for accepting the responsibility to join the dissertation committee. Finally, I thank Dr. Hendrik Schmale, Sandra Stevermüer and Alfred Koch for being great friends and colleagues. I am deeply grateful to Dagmar and Rolf Meiseberg for promoting and challenging critical thinking in any endeavours, and for being a constant source of love, concern, support and strength, all these years. I thank Prof. Dr. Frank Ückert for supporting me every step of the way. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................. -

Paul Mccartney's

THE ULTIMATE HYBRID DRUMKIT FROM $ WIN YAMAHA VALUED OVER 5,700 • IMAGINE DRAGONS • JOEY JORDISON MODERNTHE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE DRUMMERJANUARY 2014 AFROBEAT 20DOUBLE BASS SECRETS PARADIDDLE PATTERNS MILES ARNTZEN ON TONY ALLEN CUSTOMIZE YOUR KIT WITH FOUND METAL ED SHAUGHNESSY 1929–2013 Paul McCartney’s Abe Laboriel Jr. BOOMY-LICIOUS MODERNDRUMMER.com + BENNY GREB ON DISCIPLINE + SETH RAUSCH OF LITTLE BIG TOWN + PEDRITO MARTINEZ PERCUSSION SENSATION + SIMMONS SD1000 E-KIT AND CRUSH ACRYLIC DRUMSET ON REVIEW paiste.com LEGENDARY SOUND FOR ROCK & BEYOND PAUL McCARTNEY PAUL ABE LABORIEL JR. ABE LABORIEL JR. «2002 cymbals are pure Rock n' Roll! They are punchy and shimmer like no other cymbals. The versatility is unmatched. Whether I'm recording or reaching the back of a stadium the sound is brilliant perfection! Long live 2002's!» 2002 SERIES The legendary cymbals that defined the sound of generations of drummers since the early days of Rock. The present 2002 is built on the foundation of the original classic cymbals and is expanded by modern sounds for today‘s popular music. 2002 cymbals are handcrafted from start to finish by highly skilled Swiss craftsmen. QUALITY HAND CRAFTED CYMBALS MADE IN SWITZERLAND Member of the Pearl Export Owners Group Since 1982 Ray Luzier was nine when he first told his friends he owned Pearl Export, and he hasn’t slowed down since. Now the series that kick-started a thousand careers and revolutionized drums is back and ready to do it again. Pearl Export Series brings true high-end performance to the masses. Join the Pearl Export Owners Group.