The Psychological Freedom in Buddhism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

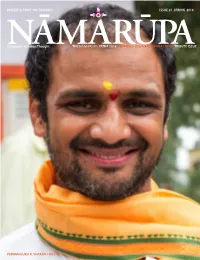

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

The Meaning of “Zen”

MATSUMOTO SHIRÕ The Meaning of “Zen” MATSUMOTO Shirõ N THIS ESSAY I WOULD like to offer a brief explanation of my views concerning the meaning of “Zen.” The expression “Zen thought” is not used very widely among Buddhist scholars in Japan, but for Imy purposes here I would like to adopt it with the broad meaning of “a way of thinking that emphasizes the importance or centrality of zen prac- tice.”1 The development of “Ch’an” schools in China is the most obvious example of how much a part of the history of Buddhism this way of think- ing has been. But just what is this “zen” around which such a long tradition of thought has revolved? Etymologically, the Chinese character ch’an 7 (Jpn., zen) is thought to be the transliteration of the Sanskrit jh„na or jh„n, a colloquial form of the term dhy„na.2 The Chinese characters Ï (³xed concentration) and ÂR (quiet deliberation) were also used to translate this term. Buddhist scholars in Japan most often used the com- pound 7Ï (zenjõ), a combination of transliteration and translation. Here I will stick with the simpler, more direct transliteration “zen” and the original Sanskrit term dhy„na itself. Dhy„na and the synonymous sam„dhi (concentration), are terms that have been used in India since ancient times. It is well known that the terms dhy„na and sam„hita (entering sam„dhi) appear already in Upani- ¤adic texts that predate the origins of Buddhism.3 The substantive dhy„na derives from the verbal root dhyai, and originally meant deliberation, mature reµection, deep thinking, or meditation. -

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 Kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas The Mind Only school evolved as a response to the possible nihilistic interpretation of the Madhyamaka school. The view “everything is mind” is conducive to the deep practice of meditational yogas. The “Tathagatagarbha”, the ‘Buddha Nature’ was derived from the experience of the Dharmakaya. Tathagata, the ‘Thus Come one’ is a name for a Buddha ( as is Sugata, the ‘Well gone One’ ). Garbha means ‘embryo’ and ‘womb’, the container and the contained, the seed of awakening . This potential to attain Buddhahood is said to be inherent in every sentient being but very often occluded by kleshas, ( ‘negative emotions’) and by cognitive obscurations, by wrong thinking. These defilements are adventitious, and can be removed by practicing Buddhist yogas and trainings in wisdom. Then the ‘Sun of the Dharma’ breaks through the clouds of obscurations, and shines out to all sentient beings, for great benefit to self and others. The 3 svabhavas, 3 kinds of essential nature, are unique to the mind only theory. They divide what is usually called ‘conventional truth’ into two: “Parakalpita” and “Paratantra”. Parakalpita refers to those phenomena of thinking or perception that have no basis in fact, like the water shimmering in a mirage. Usual examples are the horns of a rabbit and the fur of a turtle. Paratantra refers to those phenomena that come about due to cause and effect. They have a conventional actuality, but ultimately have no separate reality: they are empty. Everything is interconnected. -

The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara

Aspects of Buddhist Psychology Lecture 42: The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara Reverend Sir, and Friends Our course of lectures week by week is proceeding. We have dealt already with the analytical psychology of the Abhidharma; we have dealt also with the psychology of spiritual development. The first lecture, we may say, was concerned mainly with some of the more important themes and technicalities of early Buddhist psychology. We shall, incidentally, be referring back to some of that material more than once in the course of the coming lectures. The second lecture in the course, on the psychology of spiritual development, was concerned much more directly than the first lecture was with the spiritual life. You may remember that we traced the ascent of humanity up the stages of the spiral from the round of existence, from Samsara, even to Nirvana. Today we come to our third lecture, our third subject, which is the Depth Psychology of the Yogacara. This evening we are concerned to some extent with psychological themes and technicalities, as we were in the first lecture, but we're also concerned, as we were in the second lecture, with the spiritual life itself. We are concerned with the first as subordinate to the second, as we shall see in due course. So we may say, broadly speaking, that this evening's lecture follows a sort of middle way, or middle course, between the type of subject matter we had in the first lecture and the type of subject matter we had in the second. Now a question which immediately arises, and which must have occurred to most of you when the title of the lecture was announced, "What is the Yogacara?" I'm sorry that in the course of the lectures we keep on having to have all these Sanskrit and Pali names and titles and so on, but until they become as it were naturalised in English, there's no other way. -

Relevance of Pali Tipinika Literature to Modern World

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) Vol. 1, Issue 2, July 2013, 83-92 © Impact Journals RELEVANCE OF PALI TIPINIKA LITERATURE TO MODERN WORLD GYANADITYA SHAKYA Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization, Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Shakyamuni Gautam Buddha taught His Teachings as Dhamma & Vinaya. In his first sermon Dhammacakkapavattana-Sutta, after His enlightenment, He explained the middle path, which is the way to get peace, happiness, joy, wisdom, and salvation. The Buddha taught The Eightfold Path as a way to Nibbana (salvation). The Eightfold Path can be divided into morality, mental discipline, and wisdom. The collection of His Teachings is known as Pali Tipinika Literature, which is compiled into Pali (Magadha) language. It taught us how to be a nice and civilized human being. By practicing Sala (Morality), Samadhi (Mental Discipline), and Panna (Wisdom ), person can eradicate his all mental defilements. The whole theme of Tipinika explains how to be happy, and free from sufferings, and how to get Nibbana. The Pali Tipinika Literature tried to establish freedom, equality, and fraternity in this world. It shows the way of freedom of thinking. The most basic human rights are the right to life, freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the right to be treated equally before the law. It suggests us not to follow anyone blindly. The Buddha opposed harmful and dangerous customs, so that this society would be full of happiness, and peace. It gives us same opportunity by providing human rights. -

Explanation 1 Vinnana and Namarupa-PATICCA SAMUPPADA.Pdf

PATICCASAMUPPADA Part - II The Law of Dependent Origination Consciousness ARISES Mind and Matter 1. Avijja - ignorance or delusion 2. Sankhara - kamma-formations 3. Vinnana - consciousness 4. Nama-rupa - mind and matter 5. Salayatana - six sense bases 6. Phassa - contact or impression 7. Vedana - Feeling 8. Tanha - craving 9. Upadana - clinging 10. Bhava - becoming 11. Jati - rebirth 12. Jara-marana - old age and death Introduction – PA-TIC-CA-SA-MUP-PA-DA – the law of Dependent Origination – is very tedious to study and so is to get a clear understanding of one’s interaction of kamma’s action in the frame work of the present, past and future existence. Lesson No. 1 – Kamma Action Kamma action depends on one’s intention. An individual is not responsible for any kamma action, if he or she has committed a deed without volitional intention. The Arahant Thera CAKKHUPALA THERA was stamping on insects and many were killed, because he was blind. He has no volitional intent to kill the insects; and hence, Buddha said, he is free and not responsible for this action and therefore no kamma is generated against him. “Buddha, the Lord said that since the thera had no intention to kill the insects, he was free from any moral responsibility for their destruction. So we should note that causing death with out cetana or volition is not a kammic act. Some Buddhists have doubt about their moral purity when they cook vegetables or drink water that harbor microbes.” Page 1 of 7 Dhamma Dana Maung Paw, California Buddha said - "Cetana (volitional act) is that which I call kamma." Lesson No. -

Buddhism a Collection of Notes on Dhamma

BUDDHISM A COLLECTION OF NOTES ON DHAMMA CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PREFACE 4 INTRODUCTION TO THERAVADA BUDDHISM 5 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS 11 PART I TRIPLE GEM 12 01 – The Buddha 12 02 – Nine Attributes of Buddha 14 03 – Dhamma 14 04 – Six Attributes of Dhamma 15 05 – Sangha 15 06 – Nine Attributes of Sangha 16 07 – Going for Refuge 16 08 – Two Schools of Buddhism 17 09 – Revival of Buddhism in India 17 10 – Spread of Buddhism to the Western World 18 11 – Buddhism and the Modern Views 19 12 – Misrepresentation of Buddhism 19 1 PART II – DHAMMA DOCTRINES AND CONCEPTS FOR LIBRATION 21 01 – The First Sermon – Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion 21 02 – The Second Sermon The Notself Characteristic and Three Basic Facts of Existence 23 03 – The Fire Sermon 26 04 – The Buddha’s Teachings on Existence of Beings, their World, and Related subjects 26 05 – The Law of Kamma 30 06 – The Natural Orders or Laws of Universe 33 07 – Analysis of Dependent Coarising 33 08 – Transcendental Dependent Arising 34 09 – Human Mind 35 10 – The Moral Discipline (Sila Kkhandha) 36 11 – The Concentration Discipline (Samadhi Kkhandha) 39 12 – The Five Spiritual Faculties 41 13 – Dhammapada 43 14 – Milindapana – Questions of Milinda 45 15 – The Inner Virtue and Virtuous Actions of Sila (Perfections, Sublime States, and Blessings) 45 16 – The Buddha’s Charter of Free Inquiry (Kalama Sutta) 49 17 – Conclusion of Part II 49 2 PART III – DHAMMA FOR SOCIAL HARMONY 51 01 Big Three’s for Children 51 02 Gradual Practice of Dhamma 52 03 Moral Conducts 53 04 Moral Responsibility 54 05 Moral Downfall (Parabhava Sutta) 55 06 Conditions of Welfare (Vyagghapajja Sutta) 55 07 Social Responsibility 56 08 Burmese Way of Life 57 09 Domestic Duties 59 10 Social Duties 60 11 Spiritual Duties 61 12 Meditation, Concentration and Wisdom 62 13 – Conclusion of Part III 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY 65 3 BUDDHISM A COLLECTION OF NOTES ON DHAMMA PREFACE When I was young growing up in central Myanmar [Burma], I accompanied my religious mother to Buddhist monasteries and we took five or eight precepts regularly. -

Dhamma - for the 4Th Industrial Revolution

233 DHAMMA - FOR THE 4TH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION by A.T.Ariyaratne* I am responding to the Most Ven. Dr. Thich Nhat Tu’s invitation to send a contribution on the given subtheme of Buddhism and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Though I am no expert on Buddhism or a scholar on Industrial Revolutions, I accepted this invitation extended to me as a practitioner of Buddha’s teaching since my childhood. Besides, the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement we started six decades ago in 1958, attempted to apply Buddhism to find solutions to modern day social, political and economic issues. I was fortunate to be born into a family of Buddhists. In my country Sri Lanka, we had inherited a culture that dates back to over two thousand six hundred years. My parents, specially my mother, were my primary educators to introduce age-old traditional Buddhist ideals to us. Later these values were inculcated into our personalities as life-long practices applicable to every moment of living by the learned and virtuous monks of our village temple and the school teachers. It may be appropriate to mention one of those lessons I learnt at this point. A mosquito may land on my left hand and its bite hurts me. My right hand alights on the mosquito spontaneously. My mother sees my reaction. She calls me lovingly and makes me sit on her lap and begins to talk. “My son, look at the size of this mosquito. So tiny, you even can’t see it easily. Imagine how small his brain is. Imagine how big you are and your brain compared to the mosquito. -

The Real Christ Is Buddhi-Manas, the Glorified Divine Ego V

The real Christ is Buddhi- Manas, the glorified Divine Ego The real Christ is Buddhi-Manas, the glorified Divine Ego v. 13.13, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 21 March 2018 Page 1 of 61 THE REAL CHRIST IS BUDDHI-MANAS ABSTRACT AND TRAIN OF THOUGHTS Abstract and train of thoughts Was Jesus as Son of God and Saviour of Mankind, unique in the world’s annals? The real Saviours of Mankind all descend to the Nether World, the Kingdom of Darkness, of temptation, lust, and selfishness. And, after having overcome the Chrēst condition or the tyranny of separateness, their astral or worldly ego is enlightened by Lucifer, the Glorified Divine Ego (Buddhi-Manas), who is the real Christ in every man. 5 Pythagoras, Buddha, Apollonius, were Initiates of the same Secret School. 7 The Sun is the external manifestation of the Seventh Principle of our Planetary System while the Moon is its Fourth Principle. Shining in the borrowed robes of her Master, she is saturated with and reflects every passionate impulse and evil desire of her grossly material body, our earth. 9 Jesus as “Son of God” and “Saviour of Mankind,” was not unique in the world’s annals The “infallible” Churches made up history as they went along. 11 Building up the Apostolic Church on a jumble of contradictions. 12 See how the Fathers have falsified Jesus’ last words and made him a victim of his own success. 12 “My God, my Sun, thou hast poured thy radiance upon me!” concluded the thanksgiving prayer of the Initiate, “the Son and the Glorified Elect of the Sun.” 14 And thus his Father’s name was written on his forehead. -

ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT with SHRI R. SHARATH JOIS in Uttarkashi, Himalayas, India October 12 -17, 2015 Presented by ASHTANGA & YOGA NEW YORK

NĀMARŪPA YĀTRĀ 2015 An epic pilgrimage in two parts from Varanasi to the Himalayas various options during October 2015 & an opportunity to combine the yatra with a special ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT with SHRI R. SHARATH JOIS in Uttarkashi, Himalayas, India October 12 -17, 2015 presented by ASHTANGA & YOGA NEW YORK 1 YĀTRĀ 2015 Yatra, Tirtha and Darshan The Places We Plan to Visit (Unplanned places are in between!) of Ardhanareeswara and Viswanath. We'll pass through Chopta The ancient Puranas of India are huge volumes containing stories of We'll meet in New Delhi and take some time to greet each other with incredible views of the snowy Himalayan peaks. A short hike the makings of the universe as well as thrilling tales of innumerable and rest from our long flights. Then we'll head out to visit Hanu- will bring us to Tunganath, second most important of the Panch gods and goddesses. The geography of the Puranas coincides with man Mandir, purchase some Indian style clothing at the Khadi Kedar, the five holy abodes of Siva in the Garwhal Himalaya. Then that of the entire Indian sub-continent. Countless places mentioned (homespun) store ,and get ready for our adventure. A short flight we'll halt at Gaurikund before taking our 15-km trek (or pony ride) in these ancient texts are fully alive today and are important places of will bring us to the world's oldest continuously inhabited city, Va- to Kedarnath. This is one of the twelve spontaneously manifested yatra (pilgrimage). Within their sanctums, worship of the resident gods ranasi. -

Unit 4 Philosophy of Buddhism

Philosophy of Buddhism UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF BUDDHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Four Noble Truths 4.3 The Eightfold Path in Buddhism 4.4 The Doctrine of Dependent Origination (Pratitya-samutpada) 4.5 The Doctrine of Momentoriness (Kshanika-vada) 4.6 The Doctrine of Karma 4.7 The Doctrine of Non-soul (anatta) 4.8 Philosophical Schools of Buddhism 4.9 Let Us Sum Up 4.10 Key Words 4.11 Further Readings and References 4.0 OBJECTIVES This unit, the philosophy of Buddhism, introduces the main philosophical notions of Buddhism. It gives a brief and comprehensive view about the central teachings of Lord Buddha and the rich philosophical implications applied on it by his followers. This study may help the students to develop a genuine taste for Buddhism and its philosophy, which would enable them to carry out more researches and study on it. Since Buddhist philosophy gives practical suggestions for a virtuous life, this study will help one to improve the quality of his or her life and the attitude towards his or her life. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Buddhist philosophy and doctrines, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, give meaningful insights about reality and human existence. Buddha was primarily an ethical teacher rather than a philosopher. His central concern was to show man the way out of suffering and not one of constructing a philosophical theory. Therefore, Buddha’s teaching lays great emphasis on the practical matters of conduct which lead to liberation. For Buddha, the root cause of suffering is ignorance and in order to eliminate suffering we need to know the nature of existence. -

American Buddhism As a Way of Life

American Buddhism as a Way of Life Edited by Gary Storhoff and John Whalen-Bridge American Buddhism as a Way of Life SUNY series in Buddhism and American Culture ——————— John Whalen-Bridge and Gary Storhoff, editors American Buddhism as a Way of Life Edited by Gary Storhoff and John Whalen-Bridge Cover art: photo credit © Bernice Williams / iStockphoto.com Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2010 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production by Diane Ganeles Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data American Buddhism as a way of life / edited by Gary Storhoff and John Whalen-Bridge. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Buddhism and American culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-3093-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4384-3094-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—United States. 2. Buddhism and culture—United States. I. Storhoff, Gary. II. Whalen-Bridge, John. BQ732.A44 2010 294.30973—dc22 2009033231 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Gary Storhoff dedicates his work on this volume to his brother, Steve Storhoff.