The Dissemination of the Nyckelharpa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Folk Music

Ronström Owe 1998: Swedish folk music. Unpublished. Swedish folk music Originally written for Encyclopaedia of world music. By Owe Ronström 1. Concepts, terminology. In Sweden, the term " folkmusik " (folk music) usually refers to orally transmitted music of the rural classes in "the old peasant society", as the Swedish expression goes. " Populärmusik " ("popular music") usually refers to "modern" music created foremost for a city audience. As a result of the interchange between these two emerged what may be defined as a "city folklore", which around 1920 was coined "gammeldans " ("old time dance music"). During the last few decades the term " folklig musik " ("folkish music") has become used as an umbrella term for folk music, gammeldans and some other forms of popular music. In the 1990s "ethnic music", and "world music" have been introduced, most often for modernised forms of non-Swedish folk and popular music. 2. Construction of a national Swedish folk music. Swedish folk music is a composite of a large number of heterogeneous styles and genres, accumulated throughout the centuries. In retrospect, however, these diverse traditions, genres, forms and styles, may seem as a more or less homogenous mass, especially in comparison to today's musical diversity. But to a large extent this homogeneity is a result of powerful ideological filtering processes, by which the heterogeneity of the musical traditions of the rural classes has become seriously reduced. The homogenising of Swedish folk music started already in the late 1800th century, with the introduction of national-romantic ideas from German and French intellectuals, such as the notion of a "folk", with a specifically Swedish cultural tradition. -

Beethoven and Banjos - an Annual Musical Celebration for the UP

Beethoven and Banjos - An Annual Musical Celebration for the UP Beethoven and Banjos 2018 festival is bringing Nordic folk music and some very unique instruments to the Finnish American Heritage Center in Hancock, Michigan. Along with the musicians from Decoda (Carnegie Hall’s resident chamber group) we are presenting Norwegian Hardanger fiddler Guro Kvifte Nesheim and Swedish Nyckelharpist Anna Gustavsson. Guro Kvifte Nesheim grew up in Oslo, Norway, and started playing the Hardanger fiddle when she was seven years old. She has learned to play the traditional music of Norway from many great Hardanger fiddle players and has received prizes for her playing in national competitions for folk music. In 2013 she began her folk music education in Sweden at the Academy of Music and Drama in Gothenburg. Guro is composing a lot of music, and has a great interest and love for the old music traditions of Norway and Sweden. In 2011 she went to the world music camp Ethno and was bit by the “Ethno-bug”. Since then she has attended many Ethno Camps as a participant and leader, and setup Ethno Norway with a team of fellow musicians. In spring 2015 she worked at the Opera House of Gothenburg with the dance piece “Shadowland”. The Hardanger fiddle is a traditional instrument from Norway. It is called the Hardanger Fiddle because the oldest known Hardanger Fiddle, made in 1651, was found in the area Hardanger. The instrument has beautiful decorations, traditional rose painting, mother-of-pearl inlays and often a lion’s head. The main characteristic of the Hardanger Fiddle is the sympathetic strings that makes the sound very special – it’s like an old version of a speaker that amplifies the sound. -

1 Sotholms Och Svartlösa Härader

1 SOTHOLMS OCH SVARTLÖSA HÄRADER INNEHÅLL 2 SVARTLÖSA HÄRAD 26 ÖSMODRÄKTEN 3 PÅ BANAN 28 POLONESSEBOKEN 4 SPELMÄN 30 VEM ÄR SOM EJ... )0 DANSEN PÅ SÖDERTÖRN 32 SKIVSPALTEN 18 JAG MINNS 34 HARPOLEK 20 SÄGNER OCH MINNEN 36 SORUNDAVISAN 22 HANDLAREVISAN Omdagsbild: Byspelmannen, målad av den tyske 23 DRÄKTEN PÅ SÖDERTÖRN konstmren Hans Thoma, 1839- 1924. 24 SORUNDADRÄKTEN " '. .h %5z"f*:%:?Z? ' ""'= " " """' "É=..,, ~ "') L' . """ " ', ~j1K q' . , ,, ',. U · " "r"^ pgc. " ,\,\ b - h1· a»,' X' " am v""' ! °""'"'""" r, "=: " " - ' "::0 T' "": ±%v"4 '&" m ""' "' SY . ·:%, ·- -' ' " '" ·x"f;" '"3' " "L. .7yj|::c"^X+"m "" " ·P :k -'e ., ==9"2" ;6 ¢. ' "" , "t?:,:k ' ' "' 'l" ,'" " " W r' " QL"+:S\ja, " :" l V ,/i ,b ,, "¶%1 p -J' l" · t, · l. tk. "", ' n rtarNm. .,~ b- " 0 bm mb n g . · · K ' 0m· vf . V h~~m~' .·· 2?'' b « "brgib, 4 . .~,._+.:' " "" "".. cl Rm"m "' :__ T " " r ' . 0ybW +· M0~ f , 0m. : Q SÖRMLAN%LÅTEN dktribue ra8 till medlemmarna l Södermanland8 SpelmanMörbund och Sörmländska Ungdommngen. Utomstående kan prenumerera på Spelman8förbundet8 cirkulär (Inkl. SÖRMLANDS- LÄTEN) för ett år genom att 8åtta in kr IS: -- på postgiro 12 24 74 - O, adrem Södermanland8 Spelmam- förbund. Skriv "Cfrkulårprenumeration" på Ullongen! Upplaga: I. 750 ex Utkommer 2 gånger per år 2 GIOVANNA BASSI - PREMIÄRDANSÖS OCH SVARTLÖSA HÄRAD SÖRMLÄNDSK GODSÄGARINNA Marianne Strandberg Giovanna var dotter till den italienska hovstdhnästa- ren Stefano Bassi och hans franska hustru Angelique. Svartlösa hdrod har fött sitt namn efter tingsstCMet Hon föddes troligen 13 juni 1762 i Paris. Hon kom till SvartakSt (SvartalC$CSt) eller SvanlCSten (löt, Im troli- Sverige 1783 tilkammans med sin bror och omtalldes gen äng) där ting med Övm Tör (norra Södertöm) Nils som ballerina vid teatern samma år. -

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL No. XXVIII July, 1966 Including the Report of the EXECUTIVE BOARD for the period July 1, 1964 to June 30, 1965 INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL 21 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.l ANNOUNCEMENTS CONTENTS APOLOGIES PAGE The Executive Secretary apologizes for the great delay in publi cation of this Bulletin. A nnouncements : The Journal of the IFMC for 1966 has also been delayed in A p o l o g i e s ..............................................................................1 publication, for reasons beyond our control. We are sorry for the Address C h a n g e ....................................................................1 inconvenience this may have caused to our members and subscribers. Executive Board M e e t i n g .................................................1 NEW ADDRESS OF THE IFMC HEADQUARTERS Eighteenth C onference .......................................................... 1 On May 1, 1966, the IFMC moved its headquarters to the building Financial C r i s i s ....................................................................1 of the Royal Anthropological Institute, at 21 Bedford Square, London, W.C.l, England. The telephone number is MUSeum 2980. This is expected to be the permanent address of the Council. R e p o r t o f th e E xecutiv e Board July 1, 1964-Ju n e 30, 1965- 2 EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING S ta tem ent of A c c o u n t s .....................................................................6 The Executive Board of the IFMC held its thirty-third meeting in Berlin on July 14 to 17, 1965, by invitation of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation, N a tio n a l C ontributions .....................................................................7 directed by M. -

TOCN0004DIGIBKLT.Pdf

NORTHERN DANCES: FOLK MUSIC FROM SCANDINAVIA AND ESTONIA Gunnar Idenstam You are now entering our world of epic folk music from around the Baltic Sea, played on a large church organ and the nyckelharpa, the keyed Swedish fiddle, in a recording made in tribute to the new organ in the Domkirke (Cathedral) in Kristiansand in Norway. The organ was constructed in 2013 by the German company Klais, which has created an impressive and colourful instrument with a large palette of different sounds, from the most delicate and poetic to the most majestic and festive – a palette that adds space, character, volume and atmosphere to the original folk tunes. The nyckelharpa, a traditional folk instrument, has its origins in the sixteenth century, and its fragile, Baroque-like sound is happily embraced by the delicate solo stops – for example, the ‘woodwind’, or the bells, of the organ – or it can be carried, like an eagle flying over a majestic landscape, with deep forests and high mountains, by a powerful northern wind. The realm of folk dance is a fascinating soundscape of irregular pulse, ostinato- like melodic figures and improvised sections. The melodic and rhythmic variations they show are equally rich, both in the musical tradition itself and in the traditions of the hundreds of different types of dances that make it up. We have chosen folk tunes that are, in a more profound sense, majestic, epic, sacred, elegant, wild, delightful or meditative. The arrangements are not written down, but are more or less improvised, according to these characters. Gunnar Idenstam/Erik Rydvall 1 Northern Dances This is music created in the moment, introducing the mighty bells of the organ. -

Trollfågeln the Magic Bird

EMILIA AMPER Trollfågeln The Magic Bird BIS-2013 2013_f-b.indd 1 2012-10-02 11.28 Trollfågeln 1. Till Maria 5'00 2. G-mollpolska efter Anders Gustaf Jernberg 3'25 3. Ut i mörka natten 4'55 4. Isadoras land 3'50 5. Trollfuglen 2'25 6. Polska fra Hoffsmyran 4'02 7. Herr Lager och skön fager 3'08 8. Brännvinslåt från Torsås 2'40 9. Pigopolskan / Den glömda polskan 5'08 10. När som flickorna de gifta sig 4'05 11. Kapad 4'44 12. Bredals Näckapolska 3'01 13. Galatea Creek 3'19 14. Vals från Valsebo 8'56 TT: 59'42 Emilia Amper nyckelharpa, sång Johan Hedin nyckelharpa Anders Löfberg cello Dan Svensson slagverk, gitarr, sång Olle Linder slagverk, gitarr Helge Andreas Norbakken slagverk Stråkar ur TrondheimSolistene: Johannes Rusten och Daniel Turcina violin Frøydis Tøsse viola, Marit Aspaas cello Rolf Hoff Baltzersen kontrabas 2 Trollfågeln innehåller 14 spår som på många sätt illustrerar mig som person och mitt liv som musiker och kompositör. Här är musiken som jag brinner för, en brokig skara låtar där traditionella svenska polskor möter nykomponerad musik inspirerad av andra länders folk- musik, och av pop, rock och kammarmusik. Jag spelar och sjunger solo eller tillsammans med goda vänner från både folkmusik och klassiskt. Som 10-åring förälskade jag mig i nyckelharpan vid första ögonkastet! Barndomens direkta glädje av instrument och melodier övergick efterhand i ett växande intresse för folkmusiken som genre. Jag mötte musik och människor från hela världen, och för mig var det liksom samma språk vi alla talade, ett språk där kopplingen mellan musik och dans är direkt och självklar. -

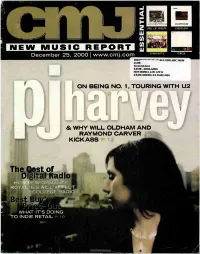

T of À1 Radio

ism JOEL L.R.PHELPS EVERCLEAR ,•• ,."., !, •• P1 NEW MUSIC REPORT M Q AND NOT U CIRCLE December 25, 2000 I www.cmj.com 138.0 ******* **** ** * *ALL FOR ADC 90198 24498 Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS 5319 HONDA AVE APT G ATASCADERO, CA 93422-3428 ON BEING NO. 1, TOURING WITH U2 & WHY WILL OLDHAM AND RAYMOND CARVER KICK ASS tof à1 Radio HOW PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES WILL AFFECT COLLEGE RADIO WHAT IT'S DOING TO INDIE RETAIL INCLUDING THE BLAZING HIT SINGLE "OH NO" ALBUM IN STORES NOW EF •TARIM INEWELII KUM. G RAP at MOP«, DEAD PREZ PHARCIAHE MUNCH •GHOST FACE NOTORIOUS J11" MONEY PASTOR TROY Et MASTER HUM BIG NUMB e PRODIGY•COCOA BROVAZ HATE DOME t.Q-TIIP Et WORDS e!' le.‘111,-ZéRVIAIMPUIMTPIeliElrÓ Issue 696 • Vol 65 • No 2 Campus VVebcasting: thriving. But passion alone isn't enough 11 The Beginning Of The End? when facing the likes of Best Buy and Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office other monster chains, whose predatory ruled that FCC-licensed radio stations tactics are pricing many mom-and-pops offering their programming online are not out of business. exempt from license fees, which could open the door for record companies looking to 12 PJ Harvey: Tales From collect millions of dollars from broadcasters. The Gypsy Heart Colleges may be among the hardest hit. As she prepares to hit the road in support of her sixth and perhaps best album to date, 10 Sticker Shock Polly Jean Harvey chats with CMJ about A passion for music has kept indie music being No. -

Engelska As Understood by Swedish Researchers and Re-Constructionists

studying culture in context Engelska as understood by Swedish researchers and re-constructionists Karin Eriksson Excerpted from: Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 Edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger First published in 2008 by The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, MacRobert Building, King’s College, Aberdeen, AB24 5UA ISBN 0-9545682-5-7 About the author: Karin Eriksson is a musicologist and researcher for the project ‘Intermediality and the Medieval Ballad’ and a lecturer in musicology at Växjö University, Sweden. Her research focuses on Swedish folk music, music festivals, and the relationships between music and dance. She is also a fiddle player and specialises in music from the western parts of Sweden. Copyright © 2008 the Elphinstone Institute and the contributors While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Elphinstone Institute, copyright in individual contributions remains with the contributors. The moral rights of the contributors to be identified as the authors of their work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. 7 Engelska as understood by Swedish researchers and re-constructionists1 KARIN ERIKSSON s part of Sweden’s traditional folk dance and music repertoire, the engelska2 has Abeen discussed many times. As is o�en the case in descriptions of traditional music and dance, the engelska is usually presented in specific contexts within specific ideological frameworks. -

Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström

Online version of Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström Stockholm, Svenskt visarkiv, 2003 Publications issued by Svenskt visarkiv 18 Translated by Kristina Radford & Andrew Coultard Illustrations: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist For additional material, go to http://old.visarkiv.se/online/online_mmm.html Contents Preface.................................................................................................. 9 AIMS, THEMES AND TERMS Aims, emes and Terms...................................................................... 13 Music as Objective and Means— Expression and Cause, · Assumptions and Questions, e Production of Difference ............................................................... 20 Class and Ethnicity, · From Similarity to Difference, · Expressive Forms and Aesthet- icisation, Visibility .............................................................................................. 27 Cultural Brand-naming, · Representative Symbols, Diversity and Multiculture ................................................................... 33 A Tradition of Liberal ought, · e Anthropological Concept of Culture and Post- modern Politics of Identity, · Confusion, Individuals, Groupings, Institutions ..................................................... 44 Individuals, · Groupings, · Institutions, Doers, Knowers, Makers ...................................................................... 50 Arenas ................................................................................................. -

Los Discos De Gentil Montaña En Los Años Sesenta: Análisis De Repertorio E Interpretación

Los discos de Gentil Montaña en los años sesenta: análisis de repertorio e interpretación José Fernando Perilla Vélez Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Artes Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Maestría en Musicología Bogotá D.C., Colombia 2018 II Los discos de Gentil Montaña en los años sesenta: análisis de repertorio e interpretación José Fernando Perilla Vélez Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Magíster en Musicología Director: Egberto Bermúdez Cujar Profesor Titular Universidad Nacional de Colombia Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Artes Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Maestría en Musicología Bogotá D.C., Colombia 2018 III “- Lo hice todo mal –dijo– y lo entendí todo al revés. La Hija de la Luna me dio muchas cosas pero, con ellas, sólo traje la desgracia sobre mí y sobre Fantasia. Doña Aiuola lo miró largo tiempo. - No –respondió–, eso no lo creo. Seguiste el camino de los deseos y ese camino nunca es derecho.” Michael Ende, La historia interminable, Cap. XXVI. IV V Agradecimientos Agradezco al profesor Egberto Bermúdez por sus clases, escritos, comentarios y difíciles lecciones; al profesor Jaime Cortés, por el auxilio en varias de ellas, por la claridad en sus apreciaciones y enseñanzas; al profesor Carlos Miñana por su buena actitud y apertura. Agradezco a mis compañeras y compañeros, con especial aprecio por Mario Sarmiento, Doris Arbeláez y Manuel Bernal, sus comentarios y el ánimo brindado. A Camilo Vaughan por las vivencias. Agradezco a Jeniffer Montaño, Asistente de la Maestría en Musicología, por sus indicaciones y recomendaciones. A Juliana Pérez por el ánimo final. Agradezco a la familia de Gentil Montaña, a sus hermanos Raúl y Carlos, su viuda Gilma y sus hijos Johnny y Germán. -

5EHC 2020 Awards Recipients

July 16, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rosanne Royer, Awards Chair (503) 871-1023 cell [email protected] Ethnic Heritage Council announces Recipients of the 2020 Annual EHC Awards to Ethnic Community Leaders and Artists The Ethnic Heritage Council (EHC) is proud to announce this year’s award recipients, to be honored at EHC’s 40th Anniversary celebration. The special event is rescheduled to Spring 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, date to be determined. The awards program with annual meeting is EHC’s major annual event. The award recipients represent extraordinary achievements and contributions to the region’s cultural and community life. We invite you to read their biographies below. The 2020 EHC Award Recipients Rita Zawaideh Bart Brashers Spirit of Liberty Award Aspasia Phoutrides Pulakis Memorial Award Randal Bays Emiko Nakamura Bud Bard Co-Recipient Co-Recipient EHC Leadership Gordon Ekvall Tracie Gordon Ekvall Tracie & Service Award Memorial Award Memorial Award Rita Zawaideh 2020 “Spirit of Liberty” Award Eestablished in 1986 and given to a naturalized citizen who has made a significant contribution to his or her ethnic community and ethnic heritage, as well as to the community at large. For decades Rita Zawaideh has been an advocate and change-maker on behalf of Middle Eastern and North African communities in the United States and around the world. She is a “one-person community information center for the Arab community,” according to the thousands who have benefited from her activism and philanthropy. “The door to Rita’s Fremont office is always open,” says Huda Giddens of Seattle’s Palestinian community, adding that Rita's strength is her ability to see a need and answer it. -

Swedish Monuments of Music and Questions of National Profiling

Lars Berglund Swedish Monuments of Music and Questions of National Profiling Symposion »Analyse und Aufklärung, ›Public History‹ und Vermarktung. Methodologie, Ideologie und gesellschaftliche Orientierung der Musikwissenschaft in (und zu) Nordeuropa nach 1945« Beitragsarchiv des Internationalen Kongresses der Gesellschaft für Musikforschung, Mainz 2016 – »Wege der Musikwissenschaft«, hg. von Gabriele Buschmeier und Klaus Pietschmann, Mainz 2018 Veröffentlicht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek (https://portal.dnb.de) und auf schott-campus.com © 2018 | Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG Lars Berglund Swedish Monuments of Music and Questions of National Profiling In an article published in 1942, the Swedish musicologist Stig Walin proposed a strategy for Swedish historical musicology. It was published in Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning (The Swedish Journal of Musicology) and titled »Methodological problems in Swedish Musicology«.1 Walin had recently earned a doctoral degree in Uppsala with a dissertation on Swedish symphonies in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. This was the first doctoral dissertation in musicology from Uppsala and awarded him the title of Docent. In the 1942 article, Walin outlines an approach to historiography and the writing of music history, strongly influenced by neo-Kantianism, but also by cultural history in the spirit of Johan Huizinga.2 Walin presents a number of methodological considerations, related to the particular conditions of the historical cultivation of music in Sweden. He suggests a scholarly focus, not only on the production of music, but also on what he designates the reproduction of music – a notion closely affiliated with what we would today call reception history.