Joint Interagency Task Force–South: the Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success by Evan Munsing and Christopher J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tightening the Belt and Introspection – Preparing for the Cut in Shekel Aid

Tightening the Belt and Introspection – Preparing for the Cut in Shekel Aid Saul Bronfeld “The Israeli Navy was always hampered by limited budgets, but achieved smart solutions… It resembles a painter, a poet – [who] creates his greatest art only on an empty stomach.” Brigadier General (ret.) Shabtai Levy1 Introduction The conference at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv on the subject of the defense industries2 can be summarized in two sentences: first, the defense industries are very important to the IDF, the economy, and the country’s outlying areas; and second, a reduction of the shekel component in US aid will have a severe negative impact on Israel’s security, the economy, and the local defense industries. Echoing these statements, most of the speakers at the conference concurred that the reduction in shekel aid was another reason to increase the defense budget for local procurement, and the sooner the better. Brigadier General (res.) Prof. Jacob Nagel, who led the drawn-out negotiations with the American authorities, was the only speaker who argued that the reduction in the shekel aid budget should also prompt some self-reflection on the part of the defense establishment. To illustrate his remarks, he recalled the collapse of Kodak, which failed to identify in advance the changing environment in which it operated. Saul (Sam) Bronfeld is a research fellow at the Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies, IDF Operations Directorate. Israel’s Defense Industry and US Security Aid 95 Sasson Hadad, Tomer Fadlon, and Shmuel Even, Editors 96 I Saul Bronfeld This article follows Nagel’s argument, and points to a matter that was not raised, but that should be before the budget is reshuffled to deal with an emerging defense-economic problem. -

Weather Reporting -- Volume C2

WEATHER REPORTING MESSAGES MÉTÉOROLOGIQUES МЕТЕОРОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ СООБЩЕНИЯ INFORMES METEOROLOGICOS VOLUME/TOM/VOLUMEN C2 TRANSMISSION PROGRAMMES PROGRAMMES DE TRANSMISSION ЛPOГPAMMЬI ЛEPEДY PROGRAMAS DE TRANSMISIÓN 2012 Weather y Climate y Water World Meteorological Organization Organisation météorologique mondiale Всемирная Метеорологическая Организация Organización Meteorológica Mundial WMO/OMM/BMO No. 9 WEATHER REPORTING MESSAGES MÉTÉOROLOGIQUES МЕТЕОРОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ СООБЩЕНИЯ INFORMES METEOROLOGICOS VOLUME/TOM/VOLUMEN C2 TRANSMISSION PROGRAMMES PROGRAMMES DE TRANSMISSION ЛPOГPAMMЬI ЛEPEДY PROGRAMAS DE TRANSMISIÓN 2012 Edition World Meteorological Organization Organisation météorologique mondiale Всемирная Метеорологическая Организация Organización Meteorológica Mundial WMO/OMM/BMO No. 9 COPYRIGHT © World Meteorological Organization © Organisation météorologique mondiale The right of publication in print, electronic and any other L’OMM se réserve le droit de publication en version imprimée form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts ou électronique ou sous toute autre forme et dans n’importe from WMO publications may be reproduced without quelle langue. De courts extraits des publications de l’OMM authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly peuvent être reproduits sans autorisation, pour autant que la indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, source complète soit clairement indiquée. La correspondance reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole relative au contenu rédactionnel -

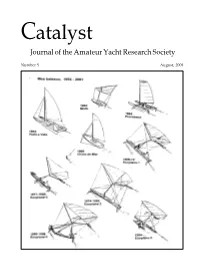

Catalyst N05 Jul 200

Catalyst Journal of the Amateur Yacht Research Society Number 5 August, 2001 Catalyst News and Views 3 Winds of Change 2001 6 Keiper Foils 7 Letters Features 10 Wind Profiles and Yacht Sails Mike Brettle 19 Remarks on Hydrofoil Sailboats Didier Costes 26 Designing Racing Dinghies Part 2 Jim Champ 29 Rotors Revisited Joe Norwood Notes from Toad Hill 33 A Laminar Flow Propulsion System Frank Bailey 36 Catalyst Calendar On the Cover Didier Costes boats (See page 19) AUGUST 2001 1 Catalyst Meginhufers and other antiquities I spent most of July in Norway, chasing the midnight sun Journal of the and in passing spending a fair amount of time in Norway’s Amateur Yacht Research Society maritime museums looking at the development history of the smaller Viking boats. Editorial Team — Now as most AYRS members will know, the Vikings rowed Simon Fishwick and sailed their boats and themselves over all of Northern Sheila Fishwick Europe, and as far away as Newfoundland to the west and Russia and Constantinople to the east. Viking boats were Dave Culp lapstrake built, held together with wooden pegs or rivets. Specialist Correspondents Originally just a skin with ribs, and thwarts at “gunwale” level, th Aerodynamics—Tom Speer by the 9 century AD they had gained a “second layer” of ribs Electronics—David Jolly and upper planking, and the original thwarts served as beams Human & Solar Power—Theo Schmidt under the decks. Which brings us to the meginhufer. Hydrofoils—George Chapman I’m told this term literally means “the strong plank”, and is Instrumentation—Joddy Chapman applied to what was once the top strake of the “lower boat”. -

586 World Political

22_Biz_in_Global_Econ MAPS 12/14/04 2:56 PM Page 586 WORLD POLITICAL MAP ARCTIC OCEAN Barrow GREENLAND Fort Yukon Port Radium Fairbanks ICELAND Nome Baker Lake Nuuk Reykjavik Rankin Inlet Torshavn Anchorage Cordova Fort Chipewyan Churchill Juneau Inukjuak Fort McMurray Bear Lake Dawson Creek Thompson Grande Prairie Flin Flon Su Prince Rupert Prince George Unalaska Prince Albert Dublin Labrador City U. K. Red Deer IRELAND Londo Saskatoon CANADA Kamloops Calgary Cork Moosonee Swift Current Vancouver Brandon Timmins Amos Williston Spokane Grand Forks Seattle Nantes Butte Duluth Ottawa Montreal Minneapolis Portland Bayonne Twin Falls MilWawkee Detroit Scottsbluff Chicago Buffalo Boston Valladolid Porto Omaha Madrid Provo New York Reno Denver Kansas City Baltimore PORTUGAL Philadelphia SPAIN Oakland U. S. A. St. Louis Washington D. C. Ponta Delgada Lisbon Sevilla San Francisco Norfolk Gibraltar Las Vegas Albuquerque Memphis Charlotte Rabat Los Angeles Atlanta Casablanca Tucson Dallas Birmingham San Diego ATLANTIC MOROCCO Houston New Orleans Jacksonville Canary Islands ALG Tampa WESTERN THE BAHAMAS MEXICO SAHARA Havana Mexico City CUBA DOM. REP. MAURITANIA Araouan JAMAICA Nouakchott BELIZE HAITI MALI HONDURAS SENEGAL Dakar GUATEMALA GAMBIA Bamako EL SALVADOR NICARAGUA BURKIN Caracas GUINEA BISSAU GUINEA Conakry GHANA IVORY T COSTA RICA Freetown VENEZUELA Georgetown COAST PACIFIC PANAMA Paramaribo SIERRA LEONE Bogota GUYANA Monrovia FRENCH GUIANA A SURINAME LIBERIA Abidjan COLOMBIA EQU SAO TOM ECUADOR Quito Belem Manaus Fortaleza Talara PERU -

DCDC Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating

Strategic Trends Programme Future Operating Environment 2035 © Crown Copyright 08/15 Published by the Ministry of Defence UK The material in this publication is certified as an FSC mixed resourced product, fully recyclable and biodegradable. First Edition 9027 MOD FOE Cover B5 v4_0.indd 1-3 07/08/2015 09:17 Strategic Trends Programme Future Operating Environment 2035 First Edition 20150731-FOE_35_Final_v29-VH.indd 1 10/08/2015 13:28:02 ii Future Operating Environment 2035 20150731-FOE_35_Final_v29-VH.indd 2 10/08/2015 13:28:03 Conditions of release The Future Operating Environment 2035 comprises one element of the Strategic Trends Programme, and is positioned alongside Global Strategic Trends – Out to 2045 (Fifth Edition), to provide a comprehensive picture of the future. This has been derived through evidence-based research and analysis headed by the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, a department within the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD). This publication is the first edition of Future Operating Environment 2035 and is benchmarked at 30 November 2014. Any developments taking place after this date have not been considered. The findings and deductions contained in this publication do not represent the official policy of Her Majesty’s Government or that of UK MOD. It does, however, represent the view of the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre. This information is Crown copyright. The intellectual property rights for this publication belong exclusively to the MOD. Unless you get the sponsor’s authorisation, you should not reproduce, store in a retrieval system or transmit its information in any form outside the MOD. -

JP 3-33, Joint Task Force Headquarters

Joint Publication 3-33 Joint Task Force Headquarters 30 July 2012 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides joint doctrine for the formation and employment of a joint task force (JTF) headquarters to command and control joint operations. It provides guidance on the JTF headquarters’ role in planning, preparing, executing, and assessing JTF operations. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations and provides the doctrinal basis for US military coordination with other US Government departments and agencies during operations and for US military involvement in multinational operations. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs) and prescribes joint doctrine for operations, education, and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing their appropriate plans. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of the overall objective. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders of combatant commands, subunified commands, joint task forces, subordinate components of these commands, the Services, and combat support agencies. b. The guidance in this publication is authoritative; as such, this doctrine will be followed except when, in the judgment of the commander, exceptional circumstances dictate otherwise. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

~'7/P64~J Adviser Department of S Vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright By

FREEDOM AND THE DON JUAN TRADITION IN SELECTED NARRATIVE POETIC WORKS AND THE STONE GUEST OF ALEXANDER PUSHKIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By James Goodman Connell, Jr., B.S., M.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1973 Approved by ,r-~ ~'7/P64~j Adviser Department of S vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright by James Goodman Connell, Jr. 1973 To my wife~ Julia Twomey Connell, in loving appreciation ii VITA September 21, 1939 Born - Adel, Georgia 1961 .•..••. B.S., United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland 1961-1965 Commissioned service, U.S. Navy 1965-1967 NDEA Title IV Fellow in Comparative Literature, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967 ••••.•. M.A. (Comparative Literature), The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967-1970 NDFL Title VI Fellow in Russian, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969 •.•••.• M.A. (Slavic Languages and Literatures), The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1970 .•...•. Assistant Tour Leader, The Ohio State University Russian Language Study Tour to the Soviet Union 1970-1971 Teaching Associate, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1971-1973 Assistant Professor of Modern Foreign Languages, Valdosta State College, Valdosta, Georgia FIELDS OF STUDY Major field: Russian Literature Studies in Old Russian Literature. Professor Mateja Matejic Studies in Eighteenth Century Russian Literature. Professor Frank R. Silbajoris Studies in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature. Professors Frank R. Silbajoris and Jerzy R. Krzyzanowski Studies in Twentieth Century Russian Literature and Soviet Literature. Professor Hongor Oulanoff Minor field: Polish Literature Studies in Polish Language and Literature. -

“NO MORE” Ending Sex Trafficking in Canada

“NO MORE” Ending Sex-Trafficking In Canada Report of the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada commissioned by the Canadian Women’s Foundation Fall 2014 2 Report of the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada “ True equality for women and girls will not be achieved until all forms of violence, including sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, are eradicated. This will require a broad perspective and action taken in all sectors and in a wide range of policy areas. The results will reflect a stronger nation whose political, social and economic inequalities are minimized and where human rights and the possibility for everyone to succeed to their greatest potential is achieved.” The Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada Report of the National Task Force 3 on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada This report summarizes the findings and recommendations of the Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada. The Task Force was created and funded by the Canadian Women’s Foundation to investigate the nature and extent of sex trafficking in Canada, and to recommend a national anti-trafficking strategy to inform the work of the Canadian Women’s Foundation. The findings and recommendations contained in this report were developed to assist the Canadian Women’s Foundation in creating its own five-year national anti-trafficking strategy. It is also hoped the recommendations will inform and offer guidance to other stakeholders working in this area. The Canadian Women’s Foundation strategy to end sex trafficking is available at www.canadianwomen.org/trafficking The Canadian Women’s Foundation’s work on sex trafficking in Canada was made possible by a generous donation from the Estate of Ann Southam, a celebrated music composer and member of the Order of Canada, to support its work with women and girls in Canada. -

Joint Interagency Task Force–South: the Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success by Evan Munsing and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 5 Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success by Evan Munsing and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by performing research and analysis, publication, conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands, to support the national strategic components of the academic programs at NDU, and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and to the broader national security community. Cover: Joint Interagency Task Force–South headquarters at Naval Air Station Key West, Florida. Photo by Linda Crippen Inset: Crossed-out snowflakes and marijuana leaves represent drug seizures. USCG (PA2 Donnie Brzuska) Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success By Evan Munsing and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 5 Series Editor: Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2011 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

The Muppets Take the Mcu

THE MUPPETS TAKE THE MCU by Nathan Alderman 100% unauthorized. Written for fun, not money. Please don't sue. 1. THE MUPPET STUDIOS LOGO A parody of Marvel Studios' intro. As the fanfare -- whistled, as if by Walter -- crescendos, we hear STATLER (V.O.) Well, we can go home now. WALDORF (V.O.) But the movie's just starting! STATLER (V.O.) Yeah, but we've already seen the best part! WALDORF (V.O.) I thought the best part was the end credits! They CHORTLE as the credits FADE TO BLACK A familiar voice -- one we've heard many times before, and will hear again later in the movie... MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) And lo, there came a day like no other, when the unlikeliest of heroes united to face a challenge greater than they could possibly imagine... STATLER (V.O.) Being entertaining? WALDORF (V.O.) Keeping us awake? MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) Look, do you guys mind? I'm foreshadowing here. Ahem. Greater than they could possibly imagine... CUT TO: 2. THE MUPPET SHOW COMIC BOOK By Roger Langridge. WALTER reads it, whistling the Marvel Studios theme to himself, until KERMIT All right, is everybody ready for the big pitch meeting? INT. MUPPET STUDIOS The shout startles Walter, who tips over backwards in his chair out of frame, revealing KERMIT THE FROG, emerging from his office into the central space of Muppet Studios. The offices are dated, a little shabby, but they've been thoroughly Muppetized into a wacky, cozy, creative space. SCOOTER appears at Kermit's side, and we follow them through the office. -

The Army and Society Forum the IDF and the PRESS DURING HOSTILITIES

The Army and Society Forum THE IDF AND THE PRESS DURING HOSTILITIES ��� ������ ������� ������ ��� ������ ��������� ��������� ��� ��� ��� ��� ����� ������ ����������� � ��������� ���� �� � ���� ���� �� ��� ������ ��������� ��������� ��� ���� ��� ������� ����� 5 Editor in Chief: Uri Dromi Administrative Director, Publications Dept.: Edna Granit English Publications Editor: Sari Sapir Translators: Miriam Weed Sari Sapir Editor: Susan Kennedy Production Coordinator: Nadav Shtechman Graphic Designer: Ron Haran Printed in Jerusalem by The Old City Press © 2003 The Israel Democracy Institute All rights reserved. ISBN 965-7091-67-5 Baruch Nevo heads The Army and Society Forum at The Israel Democracy Institute and is Professor of Psychology at Haifa University. Yael Shur is a research assistant at The Israel Democracy Institute. The views in this publication are entirely those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Israel Democracy Institute. 5 Table of Contents PART ONE The IDF and the Press during Hostilities Baruch Nevo and Yael Shur Preface 6 Introduction 7 The Media as a Strategic Consideration in Preparation for War 13 The IDF and the Media: Reciprocal Relations 21 A Research Agenda 35 PART TWO Opening Plenary Session 37 Discussion Groups Group 1: The Media as a Strategic Consideration in Preparation for War 58 Group 2: The IDF's Approach to the Media 88 Group 3: The Media’s Stance towards the IDF 119 Closing Plenary Session 139 Group Reports 151 6 The IDF and the Press during Hostilities 7 PART ONE The IDF and the Press during Hostilities Baruch Nevo and Yael Shur PREFACE The fifth meeting of the Army and Society Forum, held in the summer of 2002, dealt with issues related to the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) and the media in wartime.