Checking Today's Most Dangerous Branch from Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Principles

Parliamentary Principles . All delegates have equal rights, privileges and obligations . The majority vote decides. The rights of the minority must be protected. Full and free discussion of every proposition presented for decision is an established right of delegates. Every delegate has the right to know the meaning of the question before the assembly and what its effect will be. All meetings must be characterized by fairness and by good faith. Basic Rules of Motions 1. Motions have a definite order of precedence, each motion having a fixed rank for its introduction and consideration. 2. ONLY ONE MOTION MAY BE CONSIDERED AT A TIME. 3. No main motion can be substituted for another main motion EXCEPT that a new main motion on the same subject may be offered as a substitute amendment to the main motion. 4. All motions require a second to begin discussion unless it is from a delegation or committee or it is a simple request such as a question of privilege, a point of order or division. AMENDMENTS FOUR WAYS TO AMEND A MAIN MOTION 1. Amend by addition 2. Amend by deletion 3. Amend by addition and deletion 4. Amend by substitution TWO ORDERS OF AMENDMENTS 1. First order is an amendment to the original resolution 2. Second order is an amendment to the first order amendment. 3. No more than one order of amendment is discussed at the same time. Voting on Motions Majority vote: the calculation of the vote is based on the number of members present and voting or a majority of the legal votes cast ; abstentions are not counted; delegates who fail to vote are presumed to have waived the exercise of their right; applies to most motions Two-Thirds vote : a supermajority 2/3 vote is required when the vote restricts the right of full and free discussion: This includes a vote to TABLE, CLOSE DEBATE, LIMIT/EXTEND DEBATE, as well as to SUSPEND RULES. -

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

The Constitutionality of Legislative Supermajority Requirements: a Defense

The Constitutionality of Legislative Supermajority Requirements: A Defense John 0. McGinnist and Michael B. Rappaporttt INTRODUCTION On the first day of the 104th Congress, the House of Representatives adopted a rule that requires a three-fifths majority of those voting to pass an increase in income tax rates.' This three-fifths rule had been publicized during the 1994 congressional elections as part of the House Republicans' Contract with America. In a recent Open Letter to Congressman Gingrich, seventeen well-known law professors assert that the rule is unconstitutional.3 They argue that requiring a legislative supermajority to enact bills conflicts with the intent of the Framers. They also contend that the rule conflicts with the Constitution's text, because they believe that the Constitution's specific supermajority requirements, such as the requirement for approval of treaties, indicate that simple majority voting is required for the passage of ordinary legislation.4 t Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo Law School. tt Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. The authors would like to thank Larry Alexander, Akhil Amar, Carl Auerbach, Jay Bybee, David Gray Carlson, Lawrence Cunningham, Neal Devins, John Harrison, Michael Herz, Arthur Jacobson, Gary Lawson, Nelson Lund, Erela Katz Rappaport, Paul Shupack, Stewart Sterk, Eugene Volokh, and Fred Zacharias for their comments and assistance. 1. See RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, EFFECTIVE FOR ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS (Jan. 4, 1995) [hereinafter RULES] (House Rule XXI(5)(c)); see also id. House Rule XXI(5)(d) (barring retroactive tax increases). 2. The rule publicized in the Contract with America was actually broader than the one the House enacted. -

Parliamentary Procedure

PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE Applying Rules of Order to Keep Your Meeting Efficient And Move Your Agendas Ahead November 8, 2019 MASC/MASS State Conference Council of School Committee Administrative Personnel 091603 MOST COMMON QUESTIONS What is a quorum and a majority? When to have a roll call? What happens with a tie vote? How do abstentions affect the vote? Reconsideration vs. Rescission? Table vs. Postponement How many amendments can we have? “Friendly Amendments” Good Rules of Order Have Them. Understand them. Use Them. Follow Them. Have efficient meetings with them and not in spite of them! Knowing and Using Your Rules of Order – Why? Meetings will be run more efficiently. People are more likely to leave happier. Fewer people will be offended. Chair will appear more fair. Public perception of order and responsibility. What is Parliamentary Procedure Rules and Customs that Govern Deliberative Assemblies PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE IS NOT A BOOK CALLED ROBERT’S RULES OF ORDER. Others include Sturgis, Demeter, Cushing's, etc. WHICH RULES DO YOU USE? The law allows you to select any rules of order you choose, including your own. The law allows you to select formal published rules and to make any exceptions you wish. You may not use rules of order to circumvent or disobey formal state law including: Executive Sessions - Participation by Chair Roll Calls - Length of Debate Parliamentary Procedure Originally prepared for large assemblies Congresses, legislatures, large bodies. Some rules are antiquated and outdated. Some formal rule books are voluminous. Robert’s 11th Edition* is more than 700 pages. Lists more than 80 motions. -

Supermajority Voting Rules

Supermajority Voting Rules Richard T. Holden∗ August 1 6, 2005 Abstract The size of a supermajority required to change an existing contract varies widely in different settings. This paper analyzes the optimal supermajority re- quirement, determined by multilateral bargaining behind the veil of ignorance, where there are a continuum of possible policies. The optimum is determined by a tradeoff between reducing blocking power of small groups and reducing expropriation of minorities. We solve for the optimal supermajority require- ment as a function of the distribution of voter types, the number of voters and the degree of importance of the decision. The findings are consistent with observed heterogeneity of supermajority requirements in different settings and jurisdictions. Keywords: Supermajority, majority rule, qualified majority, special major- ity, constitutions, social contract, incomplete contracts. JEL Classification Codes: D63, D72, D74, F34, G34, H40 ∗Department of Economics, Harvard University, 1875 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA, 02138. email: [email protected]. I wish to thank Attila Ambrus, Murali Agastya, Philippe Aghion, Jerry Green, Oliver Hart, Markus Möbius, Hervé Moulin and Demian Reidel for helpful discussions, comments and suggestions. Special thanks is owed to Rosalind Dixon. 1 1Introduction Almost all agreements contain provisions governing the process by which the terms of the agreement can be changed. Often these clauses require a supermajority (more than 50%) of the parties to agree in order to make a change. Constitutions of democratic countries are perhaps the most prominent example of this. Yet the phenomenon is far more widespread. Majority creditor clauses in corporate and sovereigndebtcontractsprovidethatasupermajority of the creditors can bind other creditors in renegotiations with the borrower. -

Bicameralism

Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Elliot Bulmer © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-107-1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages of bicameralism..................................................................................... -

Threaten but Participate: Why Election Boycotts Are a Bad Idea

POLICY PAPER Number 19, March 2010 Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS Threaten but Participate: Why Election Boycotts Are a Bad Idea Matthew Frankel POLICY PAPER Number 19, March 2010 Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS Threaten but Participate: Why Election Boycotts Are a Bad Idea Matthew Frankel A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Ted Piccone, Deputy Director for Foreign Policy at Brookings; Carina Perelli, Executive Vice President of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems; and Eric Bjornlund, co-founder and principal of Democracy International for their helpful com- ments on this paper. Threaten but Participate: Why Election Boycotts Are a Bad Idea ii F OREIGN P OLICY AT B ROOKINGS T H R E AT E N B UT P ARTICI PAT E : W HY E LECTION B OYCOTTS ARE A B AD I DEA or a while, the run-up to the 2010 general them of a fair share in the constitutional drafting elections in Iraq appeared to be déjà vu all over process, and without adequate representation in Par- Fagain. The National Dialogue Front (NDF), liament, the Sunnis were unable to prevent the new a key Sunni political party, had decided to pull out constitution from passing. Potential revisions to the of the election to protest the disqualification of hun- document remain one of the key sticking points be- dreds of candidates—most notably their leader, Salah tween Iraqi Sunni and Shia. To their credit, the Sunnis al-Mutlaq—for alleged ties to the banned Ba’th Party. quickly saw the error of their ways and participated in At the last minute, the NDF walked back from the the December 2005 elections, upping their represen- brink and decided to participate, hopefully signaling tation in the Parliament eleven-fold to 55 seats, but a growing understanding that election boycotts rare- sectarian tensions remain. -

Rules of Order Adapted for Grand Juries

California Grand Jurors’ Association Rules of Order Adapted for Grand Juries Purpose Penal Code §916 authorizes each grand jury to set its own “rules of procedure.” The California Grand Jurors’ Association (CGJA) often gets requests from jurors for advice about adopting procedures to ensure that Whose Job Is It? meetings run smoothly. All grand juries want a deliberative process that is fair and decisions that are properly made and documented. It is important that the foreperson of the jury know how to run a Some jurors with previous experience as members of boards or successful meeting, keep the commissions have expertise in operating under formal meeting discussion on track, and ensure that procedures or parliamentary rules, such as Robert’s Rules of Order. Such everyone has a chance to be heard. expertise can be helpful, but adhering to formal rules can also stifle or However, it is often difficult for the intimidate jurors who lack familiarity with them. In addition, some foreperson alone to keep track of all parliamentary rules designed for large legislative bodies or public the details of the agenda, the action meetings would rarely, if ever, apply to grand jury deliberations. items for discussion, and the rules. A grand jury can empower someone CGJA has developed this short primer of our best practices advice on rules else to assist the foreperson with of order to assist grand juries to establish some reasonable rules to some or all of these meeting govern meetings in a collegial and professional manner. Your grand jury management tasks. Monitoring the can modify or simplify these rules to meet your needs – or write your own meeting guidelines or rules of order rules of order. -

How Majority Rule Protects Minorities

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.demo.uci.edu This paper demonstrates that majority rule is the decision rule that provides most protection for the worst-off minority. Dahl (1956, 1988) argues that the values of popular sovereignty and political equality dictate the use of majority rule. However, there are other values that we need to take into account besides popular sovereignty and political equality, notably the protection of minority rights and stability. Thus it is commonly argued that there is a trade- off between political equality (maximized by majority rule) and minority protection (better provided by systems with external checks and balances, which require more than a simple majority to enact legislation). This paper argues that this trade-off does not exist and that actually majority rule provides most protection to minorities. Furthermore it does so precisely because of the instability inherent in majority rule. Majority rule is the only decision rule that completely satisfies political equality. May (1952) shows that majority rule is the only positively responsive voting rule that satisfies anonymity (all voters are treated equally) and neutrality (all alternatives are treated equally). If we use a system other than majority rule, then we lose either anonymity or neutrality. That is to say, either some voters must be privileged over others, or some alternative must be privileged over others. With super-majority voting, the status quo is privileged–if there is no alternative for which a super-majority votes, the status quo is maintained. Following Rae’s (1975) argument, given that the status quo is more desirable to some voters than to others, some voters are effectively privileged. -

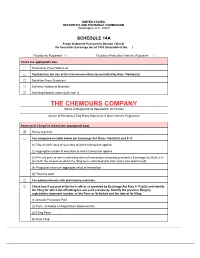

THE CHEMOURS COMPANY (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ☒ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ☐ Check the appropriate box: ☐ Preliminary Proxy Statement ☐ Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ☐ Definitive Proxy Statement ☒ Definitive Additional Materials ☐ Soliciting Material under §240.14a-12 THE CHEMOURS COMPANY (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): ☒ No fee required. ☐ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ☐ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ☐ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its -

States with Legislative Supermajority Requirements to Increase Taxes, 2010

5-Apr-13 States with Legislative Supermajority Requirements to Increase Taxes, 2010 Year Initiative/ Vote State Major Features of the Requirement Adopted Referendum Required Arizona 1992 I 2/3 Applies to all tax increases. Arkansas 1934 R 3/4 Applies to all tax increases except those related to sales and alcohol. California 1979 I 2/3 Applies to all tax increases. Applies to all tax increases. Tax increases automatically sunset unless Colorado 1 1992 I 2/3 approved by the voters at the next election. Delaware 1980 R 3/5 Applies to all tax increases. Applies to increases in the corporate income tax only. The state Constitution limits the corporate income tax rate to 5%. A 3/5 vote in the Florida 1971 R 3/5 legislature is needed to surpass 5%. If voters are asked to approve the tax increase, it must be approved by 60% of those voting. Applies to all tax increases. Increases are voted on by the legislature in Kentucky 2000 R 3/5 odd-numbered years. Louisiana 1966 R 2/3 Applies to all tax increases. Michigan 1994 R 3/4 Applies to increases in the state property tax only. Mississippi 1970 R 3/5 Applies to all tax increases. Applies to all tax increases. If the governor declares an emergency, the Missouri 1 1996 R 2/3 legislature can raise taxes by a 2/3 vote; otherwise, tax increases over approximately $70 million need voter approval to pass. Nevada 1996 I 2/3 Applies to all tax increases. Oklahoma 1992 I 3/4 Applies to all tax increases.