Pom Submission 21 Pom Submission 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wader Records and Observations in Mid-Southern Victoria, 1963-1965 by F

246 SMITH, Wader Records, 1963-65 [ Bird Watcher However, a few minutes later, it rose up from the reeds and flew for about one hundred yards to a line of cyprus trees, where it disappeared into the dense foliage at the top of one of the tallest trees. During this flight it was harried persistently by two Welcome Swallows (Hirundo neoxena). The European Little Bittern, which is only of subspecific difference to the Australian bird, has been observed to perch in trees, but the habit is unusual and apparently it is confined to migrants on their · annual journey to and from Africa. F. C. R. Jourdain, in The Handbook of British Birds, Vol. 3, p. 153, discussing the cryptic postures of the European race, states that the Little Bittern "has even been known to allow itself to be captured with hand". Charles F . Belcher, in The Birds of the District of Geelong, Australia (1914), writes, "Mr. J. F. Mulder has a specimen which his son caught with his hand, after some manoeuvring on his part, and not a little fight shown by the bird". Another live capture is recorded by A. J. Campbell in Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds (1909). -M. J. Carter, Frankston, Victoria. 19 I 1/66. Wader Records and Observations in Mid-Southern Victoria, 1963-1965 By F. T. H. SMITH, Kew, Victoria The ensuing records and notes, on the Charadriiformes, are from my personal encounters with birds of the group between ap proximately August 1963 and May 1965. In this period, two complete north-south migratory wader movements by several species, and one complete east-west movement by a single species, the Double-banded Dotterel (Charadrius bicinctus), were ex perienced. -

DUCK HUNTING in VICTORIA 2020 Background

DUCK HUNTING IN VICTORIA 2020 Background The Wildlife (Game) Regulations 2012 provide for an annual duck season running from 3rd Saturday in March until the 2nd Monday in June in each year (80 days in 2020) and a 10 bird bag limit. Section 86 of the Wildlife Act 1975 enables the responsible Ministers to vary these arrangements. The Game Management Authority (GMA) is an independent statutory authority responsible for the regulation of game hunting in Victoria. Part of their statutory function is to make recommendations to the relevant Ministers (Agriculture and Environment) in relation to open and closed seasons, bag limits and declaring public and private land open or closed for hunting. A number of factors are reviewed each year to ensure duck hunting remains sustainable, including current and predicted environmental conditions such as habitat extent and duck population distribution, abundance and breeding. This review however, overlooks several reports and assessments which are intended for use in managing game and hunting which would offer a more complete picture of habitat, population, abundance and breeding, we will attempt to summarise some of these in this submission, these include: • 2019-20 Annual Waterfowl Quota Report to the Game Licensing Unit, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries • Assessment of Waterfowl Abundance and Wetland Condition in South- Eastern Australia, South Australian Department for Environment and Water • Victorian Summer waterbird Count, 2019, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research As a key stakeholder representing 17,8011 members, Field & Game Australia Inc. (FGA) has been invited by GMA to participate in the Stakeholder Meeting and provide information to assist GMA brief the relevant Ministers, FGA thanks GMA for this opportunity. -

Regional Bird Monitoring Annual Report 2018-2019

BirdLife Australia BirdLife Australia (Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) was founded in 1901 and works to conserve native birds and biological diversity in Australasia and Antarctica, through the study and management of birds and their habitats, and the education and involvement of the community. BirdLife Australia produces a range of publications, including Emu, a quarterly scientific journal; Wingspan, a quarterly magazine for all members; Conservation Statements; BirdLife Australia Monographs; the BirdLife Australia Report series; and the Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. It also maintains a comprehensive ornithological library and several scientific databases covering bird distribution and biology. Membership of BirdLife Australia is open to anyone interested in birds and their habitats, and concerned about the future of our avifauna. For further information about membership, subscriptions and database access, contact BirdLife Australia 60 Leicester Street, Suite 2-05 Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Tel: (Australia): (03) 9347 0757 Fax: (03) 9347 9323 (Overseas): +613 9347 0757 Fax: +613 9347 9323 E-mail: [email protected] Recommended citation: BirdLife Australia (2020). Melbourne Water Regional Bird Monitoring Project. Annual Report 2018-19. Unpublished report prepared by D.G. Quin, B. Clarke-Wood, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks and K. Herman for Melbourne Water by (BirdLife Australia, Carlton) This report was prepared by BirdLife Australia under contract to Melbourne Water. Disclaimers This publication may be of assistance to you and every effort has been undertaken to ensure that the information presented within is accurate. BirdLife Australia does not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Seasonal Patterns in Abundance of Waterfowl

Corella,2004, 28(3): 61-67 SEASONALPATTERNS IN ABUNDANCEOF WATERFOWL(ANATIDAE) AT A WASTESTABILIZATION POND IN VICTORIA ANDREW J. HAMILTONIr and IAIN R. TAYLORI 'AppliedOrnithology Group, Johnstone Centre, School of Environmentaland InformationSciences, Charles Sturt University,PO Box 789, Albury, New SouthWales. Auslralia 2640 :Correspondingauthor (Currenl Address): Primary Industri€s Rcscarch Victoria (Knoxfield), Privatc Bag 15, FerntreeGully DeliveryCentre, Victoria, Australia3156 Received:2 Novenber2003 The seasonal abundanceof waterfowlon a waste stabilizationpond at the Western TreatmentPlant, Victoria, Australia,was studied over two years. The abundancesof species that are considered to be highly dispersive, such as the Pink'eared Duck Malacorhynchusmembranaceus and Grey Teal Anas gracilis, were erratic and inconsistentacross the two years. For other species, such as the AustralasianShoveler /nas rhynchotis,Blaak Swan Cygnus atratus, Pacific Black Duck /nas superciliosaand AustralianShelduck Tadoma tadornoides,mote consistentpatterns were observed each year. Most species used the site during what would be expectedto be their non-breedingseason. Australian Shelducks appeared to use the site as a late-spring/early-summermoulting reluoe. INTRODUCTION Pond Nine of the WTP, and draw comparisonswith previouslypublished work. The Westem Treatment Plant (WTP) at Werribee. Victoria, is known to support large numbers of waterfowl of several species (Lane and Peake 1990), and forms part MATERIALSAND METHODS of a Wetland of International Significance (Ramsar ConventionBureau 1984). A Iargewaste stabilization pond Study site within the WTP, known as Pond Nine in the Lake Borrie The WTP occupies an area of 10851 hectaresand is situated35 system,is consideredto be of particular importancefor kilometrcs wcst of Melbourne on the shores of Por( Phillip Bay waterfowl and other waterbirds(Elliget 1980; Hamilton (38"00'5, 144"34'E).A location map is provided in Hamilron ?r dl. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I .F

I I MELBOURNE DOCKLANDS STRATEGIC OPTIONS I I CONSULTANTS' REPORT No. I 8.2.2.5b I Ground contamination overview study I / I I I I I I I I I I DOCK LANDS I 711.5 TASK FORCE 099451 DOC strategic I options cr I . f I IN[I~iiliil~ir M0045880 I I DOCKLANDSTASKFORCE I I I I MELBOURNE DOCKLANDS REDEVELOPMENT I I Final Report on I GROUND CONTAMINATION OVERVIEW STUDY I ...~'.".~ . ~ . .~~ , I I Infrastructure Library May 1990 I I I I CAMP SCOTT FURPHY PTY. LTD. in association with I GOLDER ASSOCIATES PTY. LTD. II I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 711.5 DOI07583 099451 DOC Melbourne docklands I strategic strategic options: options cr consultants' report f I I I I I I I DOCKLANDSTASKFORCE MELBOURNE DOCKLANDS REDEVELOPMENT I GROUND CONTAMINATION OVERVIEW STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS I, PAGE NO. I 1. INTRODUCTION 2. STUDY SCOPE 2 I 2.1 General 2 I 2.2 Study Limitations 4 3. SITE DATA 5 I 3.1 Geology 5 3.2 Site History 7 I 3.3 Industrialalnd Commercial Heritage 11 I 3.4 Present Land-use 14 4. PRELIMINARY CONTAMINATION ASSESSMENT 15 I 4.1 General 15 'I 4.2 Impact of Land Reclamation 17 4.3 Impact of Industry 19 I 4.4 Potential Ground and Groundwater Contamination 21 5. REMEDIATION STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT 24 I 5.1 General 24 I 5.2 Factors Influencing the Selection of a Site Remediation 24 5.3 Appropriate Remediation Technologies 25 I 5.4 Remediation Requirements 27 I 6. -

Appendix 1 Citations for Proposed New Precinct Heritage Overlays

Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review Appendix 1 Citations for proposed new precinct heritage overlays © Biosis 2017 – Leaders in Ecology and Heritage Consulting 183 Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review A1.1 City Road industrial and warehouse precinct Place Name: City Road industrial and warehouse Heritage Overlay: HO precinct Address: City Road, Queens Bridge Street, Southbank Constructed: 1880s-1930s Heritage precinct overlay: Proposed Integrity: Good Heritage overlay(s): Proposed Condition: Good Proposed grading: Significant precinct Significance: Historic, Aesthetic, Social Thematic Victoria’s framework of historical 5.3 – Marketing and retailing, 5.2 – Developing a Context: themes manufacturing capacity City of Melbourne thematic 5.3 – Developing a large, city-based economy, 5.5 – Building a environmental history manufacturing industry History The south bank of the Yarra River developed as a shipping and commercial area from the 1840s, although only scattered buildings existed prior to the later 19th century. Queens Bridge Street (originally called Moray Street North, along with City Road, provided the main access into South and Port Melbourne from the city when the only bridges available for foot and wheel traffic were the Princes the Falls bridges. The Kearney map of 1855 shows land north of City Road (then Sandridge Road) as poorly-drained and avoided on account of its flood-prone nature. To the immediate south was Emerald Hill. The Port Melbourne railway crossed the river at The Falls and ran north of City Road. By the time of Commander Cox’s 1866 map, some industrial premises were located on the Yarra River bank and walking tracks connected them with the Sandridge Road and Emerald Hill. -

LIFE on the BEND a Social History of Fishermans Bend, Melbourne

LIFE ON THE BEND A social history of Fishermans Bend, Melbourne Prepared for Fishermans Bend Taskforce, July 2017 people place heritage REPORT REGISTER This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled ‘Life on the Bend: A social history of Fishermans Bend, Melbourne’ undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Description Issued Issued to No. No. date 2190 1 Draft Social History 11.05.17 Andrea Kleist 2190 2 Draft Social History 14.06.17 Andrea Kleist 2190 3 Final Social History 21.07.17 Andrea Kleist © Context Pty Ltd 2017 Project Team: Dr Helen Doyle, Principal author Chris Johnston, Project manager Jessica Antolino, Consultant Cover images (clockwise from top left): Samantha Willis, Support Young gardeners, Montague Free Kindergarten, c.1920s (source: VPRS 14562, P13, Unit 1, Item 5, PROV); Walking in the sand and wind at Fishermans Bend, c.1880s (source: Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria); Context Pty Ltd ‘Distributing the food at the South Melbourne Depot’, with inset: ‘Giving away fresh fish’, Illustrated Australian 22 Merri Street, Brunswick VIC 3056 News, 1 May 1894 (source: Brian Dickey, No Charity There, 1981, p. 102); Delivery trucks leaving John Kitchen & Sons factory in Ingles Street, Fishermans Bend, c.1920s (source: Port Phone 03 9380 6933 Melbourne Historical and Preservation Society); Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Fishermans Bend today (source: Fishermans Bend website: http://www.fishermansbend.vic.gov.au/); Email [email protected] Detail from Henry Burn, ‘Train to Sandridge’, 1870 depicting the open country around Emerald Hill (source: Web www.contextpl.com.au Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria). -

Werribee Catchment Preliminary Targets Go to Table of Contents

Healthy Waterways Strategy Werribee Catchment Preliminary Targets Go to Table of Contents Developed to support Werribee Catchment Collaboration PRELIMINARY Page 1 of 39 For more information about this project please call the Healthy Waterways Strategy team on 131 722. For an interpreter Visit us Like us Follow us Please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 13 14 50 https://yoursay.melbournewater.com.au/healthy-waterways facebook.com/melbournewater @MelbourneWater TableTable of Contents of Contents WerribeeWerribee Catchment Catchment Preliminary Preliminary Targets Targets Go toGo Cover to Cover Sheet Sheet SectionSection & Sheet & Sheet Titles Titles PagesPages 3. Target3. Target Summaries Summaries 3 3 3.1. 3.1.CatchmentCatchment Summary Summary 4 4 a. Werribeea. Werribee Catchment Catchment 5 5 3.2. 3.2.WaterwaysWaterways Management Management Unit UnitSummaries Summaries 6 6 a. Werribeea. Werribee River RiverUpper Upper 7 7 b. Werribeeb. Werribee River RiverMiddle Middle 8 8 c. Werribeec. Werribee River RiverLower Lower 9 9 d. Cherryd. Cherry Main Main Drain Drain 10 10 e. Lerderderge. Lerderderg River River 11 11 f. Parwanf. Parwan Creek Creek 12 12 g. Kororoitg. Kororoit Creek Creek Upper Upper 13 13 h. Kororoith. Kororoit Creek Creek Lower Lower 14 14 i. Lavertoni. Laverton Creek Creek 15 15 j. Skeletonj. Skeleton Creek Creek 16 16 k. Toolernk. Toolern Creek Creek 17 17 l. Lollypopl. Lollypop Creek Creek 18 18 m. Littlem. LittleRiver RiverUpper Upper 19 19 n. Littlen. LittleRiver River Lower Lower 20 20 3.3. 3.3.EstuaryEstuary Summaries Summaries 21 21 a. Kororoita. Kororoit Creek Creek 22 22 b. Lavertonb. Laverton Creek Creek 23 23 c. -

Gee Long Investigation Area

DEVELOPMENT AREAS ACT 1973 GEE LONG INVESTIGATION AREA . '.• 711. 4099 . 452 GEE:V r---------------. ~eM~ oEPAR1MENT-0F '{ I PLANN\NG- L\BRAR ~~~~i~l~ii~iil~~ .'J g~~STRY FOR PLANNING 71 3 7 M0002826 ANQ EN)LIBONME!il J.,JBBABY I DEVELOPMENT AREAS ACT 1973 I G E E L 0 N G I N V E S T I G A T I 0 N A R E A I (Municipal districts of City of Geelong, City of Geelong West, City of Newtown, Borough of Queenscliffe, Shire of Bannockburn, Shire of Bellarine and parts of the municipal districts of Shire of Corio, City of South Barwon and Shire I of Barrabool). I REPORT CONTENTS I PAGE I Chapter 1 Surrmary 1-2 Chapter 2 Bac~ground to the Study 3.:.6 I Chapter 3 The Geelong Region 7-13 Chapter 4 . Pl arini ng Po 1icy, Submissions and En vi ronmenta 1 14-17 I Considerations Chapter 5 Goals and Objectives for the Geelong Region 18-20 I Chapter 6 Constraints on Development 21-32 I· Chapter 7 Location of Growth in the Region 33-34 Chapter 8 Development of a Regional Strategy 35-42 I Chapter 9 Management and Implementation 43-46 Chap~er 10 Recommendation 47 I Chapter 11 Requirements of the Development Areas Act 48-53 I APPENDICES 1. Sites of Aboriginal Relics 54 I 2. Submissions Received Regarding Geelong Investigation 55 Area I 3. Register of Historic Buildings - Geelong Region 56 I 4. Sites of Special Scientific Interest 57-59 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 60 I TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING BOARD :I 22ND SEPTEMBER, 1975. -

Submission Cover Sheet Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee EES 3104

Submission Cover Sheet Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee EES 3104 Request to be heard?: No Full Name: Steph Miller Organisation: Address of affected property: Attachment 1: Attachment 2: Attachment 3: Submission: My name is Steph Miller and I care about the environment in Westernport Bay. Westernport bay is an area of considerable biodiversity and is listed on the Australia heritage registrar. We are rapidly destroying nature and cannot continue like this. Embrace renewable energy and give your kids a future. I thank the Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee and the Minister for Planning for the opportunity to make a submission to the environment assessment of the Crib Point gas import jetty and gas pipeline project. There are a variety of issues which should deem this proposal unacceptable under its current form and that I will point to in my submission but the issue that concerns me most is the impact on our internationally recognised wetlands and wildlife. A new fossil fuel project like the gas import terminal which AGL is proposing would introduce new risks to the local community and visitors to the area. These risks include exposing people to toxic hydrocarbons which may leak from the facility and increased risk of accidental fire and explosion as noted in EES Technical Report K. The nearest homes to the import facility are about 1.5 kms away and Wooleys Beach is also close to the site. AGL have completed only preliminary quantitative risk assessments on these risks and have deemed the risk acceptable on that basis. It is not acceptable to present preliminary studies and the EES should not continue until we have an independent expert to provide final risk assessments. -

The Coode Island Fires 20 Years on - Ian F Thomas

I F Thomas & Associates www.ifta.com.au [email protected] • Chemical, Environmental, Process Safety, Loss-Prevention, Risk and Forensic Engineers • • OHS Consultants • Occupational Hygienists • Town Planning Advisors The Coode Island Fires 20 years on - Ian F Thomas 1.0 Introduction The 20th anniversary of the Coode Island fires was remembered in the emergency access road adjacent to the Terminals Pty Ltd facility on Sunday, 21st August 2011. A group comprising MFB, CFA, council representatives and residents met four of the fire-fighters who were present and listened to talks by the fire chief at the scene, Keith Adamson and the MFB CEO, Nick Easy. Much progress has been made in the management of safety not only at the site where the fires occurred, but at all others storing dangerous goods at the Port of Melbourne Corporation Coode Island Bulk Liquids Terminalling Facility. Fire fighting systems have been upgraded, tanks nitrogen-blanketed, discharges incinerated before entering the atmosphere and impervious synthetic clay mats installed beneath storage tanks to reduce ground pollution. What concerns me however, is the fact that those who know what really happened are still not talking. In response to a paper I prepared on the accident back in 1995 and submitted to the company for comment, I enjoyed an hour-long conversation with a senior official of the company. He told me that if I publish the paper, the company will sue me. He also said that he knows what happened and if he told me, I would ‘fall off my chair’. He then said ‘but I am not going to’. -

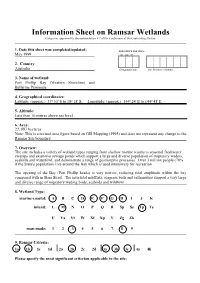

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. May 1999 DD MM YY 2. Country: Australia Designation date Site Reference Number 3. Name of wetland: Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula 4. Geographical coordinates: Latitude: (approx.) 370 53' S to 380 18' S; Longitude: (approx.) 1440 24' E to 1440 48' E 5. Altitude: Less than 10 metres above sea level. 6. Area: 22, 897 hectares Note: This is a revised area figure based on GIS Mapping (1995) and does not represent any change to the Ramsar Site boundary. 7. Overview: The site includes a variety of wetland types ranging from shallow marine waters to seasonal freshwater swamps and extensive sewage ponds which support a large and diverse population of migratory waders, seabirds and waterfowl; and demonstrate a range of geomorphic processes. Over 3 million people (70% if the State's population) live around the Bay which is used intensively for recreation. The opening of the Bay (Port Phillip heads) is very narrow, reducing tidal amplitude within the bay compared with in Bass Strait. The intertidal mudflats, seagrass beds and saltmarshes support a very large and diverse range of migratory wading birds, seabirds and wildfowl. 8. Wetland Type: marine-coastal: A B C D E F G H I J K inland: L M N O P Q R Sp Ss Tp Ts U Va Vt W Xf Xp Y Zg Zk man-made: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9.