Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Labor Shadow Ministry January 2021

Federal Labor Shadow Ministry January 2021 Portfolio Minister Leader of the Opposition The Hon Anthony Albanese MP Shadow Cabinet Secretary Senator Jenny McAllister Deputy Leader of the Opposition The Hon Richard Marles MP Shadow Minister for National Reconstruction, Employment, Skills and Small Business Shadow Minister for Science Shadow Minister Assisting for Small Business Matt Keogh MP Shadow Assistant Minister for Employment and Skills Senator Louise Pratt Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Shadow Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy MP Shadow Assistant Minister to the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator Jenny McAllister Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Minister for Home Affairs Shadow Minister for Immigration and Citizenship Shadow Minister for Government Accountability Shadow Minister for Multicultural Affairs Andrew Giles MP Shadow Minister Assisting for Immigration and Citizenship Shadow Minister for Disaster and Emergency Management Senator Murray Watt Shadow Minister Assisting on Government Accountability Pat Conroy MP Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations The Hon Tony Burke MP Shadow Minister for the Arts Manager of Opposition Business in the House of Representatives Shadow Special Minister of State Senator the Hon Don Farrell Shadow Minister for Sport and Tourism Shadow Minister Assisting the Leader of the Opposition Shadow Treasurer Dr Jim Chalmers MP Shadow Assistant -

Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

PARLIAMENT OF AUSTRALIA Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade JSCFADT membership or Senate may also ask the Committee to undertake an inquiry. Information online Introduction The Joint Standing Committee The Committee may initiate its own inquiries into annual The JSCFADT is the largest committee of the Australian reports of relevant Government departments and authorities Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Welcome from the Australian Parliament’s Joint Standing on Foreign Affairs, Defence Parliament with 32 members. Membership comprises: or reports of the Auditor-General. www.aph.gov.au/jfadt Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. and Trade • Five Senators and 12 House of Representatives Members An inquiry is based on the terms of reference – essentially The Parliament of Australia The Committee draws its membership from both the Senate from the governing party. a statement of the topic or issues to be examined. Usually, www.aph.gov.au and House of Representatives, with members sharing a Like many other legislatures, the Australian Parliament • Five Senators and eight House of Representatives inquiries are delegated to the relevant sub-committee to Department of Defence common interest in national security, international affairs and has established a system of committees. Australian Members from the opposition party. complete on behalf of the full Committee. www.defence.gov.au Australia’s role in the world. parliamentary committees each have a defined area of interest, such as the environment or economics. The Joint • Two Senators from a minority party or who are To complete the inquiry process, the Committee (or a Through its public inquiries and reports to Parliament, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and independents. -

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of Personal Ideology in Politician's

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of personal ideology in politician's speeches on Same Sex Marriage Preliminary and incomplete 2020-09-17 Current Version: http://eamonmcginn.com/papers/Same_Sex_Marriage.pdf. By Eamon McGinn∗ There is an emerging consensus in the empirical literature that politicians' personal ideology play an important role in determin- ing their voting behavior (called `partial convergence'). This is in contrast to Downs' theory of political behavior which suggests con- vergence on the position of the median voter. In this paper I extend recent empirical findings on partial convergence by applying a text- as-data approach to analyse politicians' speech behavior. I analyse the debate in parliament following a recent politically charged mo- ment in Australia | a national vote on same sex marriage (SSM). I use a LASSO model to estimate the degree of support or opposi- tion to SSM in parliamentary speeches. I then measure how speech changed following the SSM vote. I find that Opposers of SSM be- came stronger in their opposition once the results of the SSM na- tional survey were released, regardless of how their electorate voted. The average Opposer increased their opposition by 0.15-0.2 on a scale of 0-1. No consistent and statistically significant change is seen in the behavior of Supporters of SSM. This result indicates that personal ideology played a more significant role in determining changes in speech than did the position of the electorate. JEL: C55, D72, D78, J12, H11 Keywords: same sex marriage, marriage equality, voting, political behavior, polarization, text-as-data ∗ McGinn: Univeristy of Technology Sydney, UTS Business School PO Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia, [email protected]). -

FEDERAL SHADOW MINISTRY 28 January 2021

FEDERAL SHADOW MINISTRY 28 January 2021 TITLE SHADOW MINISTER OTHER CHAMBER Leader of the Opposition The Hon Anthony Albanese MP Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Cabinet Secretary Senator Jenny McAllister Deputy Leader of the Opposition The Hon Richard Marles MP Shadow Minister for National Reconstruction, Employment, Skills and Small Business The Hon Richard Marles MP Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Minister for Science The Hon Richard Marles MP Senator Murray Watt Shadow Minister Assisting for Small Business Matt Keogh MP Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Assistant Minister for Employment and Skills Senator Louise Pratt Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Senator the Hon Penny Wong The Hon Brendan O’Connor MP Shadow Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy MP Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Assistant Minister to the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator Jenny McAllister Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Minister for Home Affairs Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally The Hon Brendan O’Connor MP Shadow Minister for Immigration and Citizenship Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally The Hon Brendan O’Connor MP Shadow Minister for Government Accountability Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Pat Conroy MP Shadow Minister for Multicultural Affairs Andrew Giles MP Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Minister Assisting for Immigration and Citizenship Andrew Giles MP Senator the -

View a PDF Version of the Full Special

Most Influential SPECIAL REPORT Most Influential FEATURE LOCK STEP: Mark McGowan and Bill Shorten with Madeleine King (rear left) and Roger Cook (rear, right). Photo: Gabriel Oliveira Election set to spark power shift The looming federal election could mark a big shift in political power, not just in Canberra but also WA. Shorten are clear signals a fed- the west; that number has not There are currently no unexpected retirement in June eral election is getting close. changed, although the seniority Western Australians in the 2018. The election is tipped for mid- of the WA contingent has, shadow cabinet. When Business News asked May and, judging by numerous especially with the pending The most senior WA Mr Shorten last month about the opinion polls, Labor is favoured retirement of former foreign representative in Bill Shorten’s prospects of having a Western to win. minister Julie Bishop. team is shadow consumer Australian in his cabinet, he A Labor government under Experienced ministers affairs minister Madeleine replied: “Good, if you vote for Bill Shorten would bring about Mathias Cormann, Christian King, in the outer ministry. them”. a major shift from coalition Porter and Michaelia Cash have A former chief operating However, as Peter Kennedy policies, while a shift in power been joined in cabinet by Linda officer at the Perth USAsia explains on page 50, it is Labor’s Mark Beyer at the national level would also Reynolds (defence industry) and Centre at the University of caucus – not the leader – that [email protected] bring major changes in Western Melissa Price (environment). -

House of Representatives - Western Australia*

House of Representatives - Western Australia* Sitting members in BOLD | *Current 1 June 2016 Labor Liberal Greens National Email Electorate Candidate Email Candidate Email candidate Email Candidate Madeleine [email protected] Craig [email protected] Dawn Jecks [email protected] Brand King g.au Buchanan l.org.au Matt [email protected] Matt Muhammad [email protected] [email protected] Burt Keogh u O'Sullivan Salman Barry Andrew [email protected] Aeron Blundell- [email protected] [email protected] Canning Winmar Hastie ov.au Camden m [email protected] Anne Aly Sheridan Young [email protected] Cowan [email protected] Luke Simpkins v.au curtinco- Melissa [email protected]. Viv Glance [email protected]. Callanan au Curtin [email protected] Julie Bishop au Carol [email protected] Ian James Durack Martin [email protected] Melissa Price v.au [email protected] Lorrae [email protected] Jill Reading [email protected] Forrest Loud [email protected] Nola Marino .au Josh http://www.pierrettekelly. [email protected]. joshforfremantle@walabor. Pierrette Kelly Kate Davis Wilson com.au/contact-pierrette/ au Fremantle org.au Bill [email protected] [email protected] Hasluck Leadbetter [email protected] Ken Wyatt u Patrick Hyslop ens.org.au Ian ian.goodenough.mp@aph. Daniel Lindley Moore Goodenough gov.au [email protected] [email protected] John John.hassell@nation Jon Ford [email protected] O'Connor [email protected] Rick Wilson u Giz Watson Hassell alswa.com Thomas Christian christian.porter.mp@aph. -

The Australian Capital Territory New South Wales

Names and electoral office addresses of Federal Members of Parliament The Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................................................... 1 New South Wales ............................................................................................................................... 1 Northern Territory .............................................................................................................................. 4 Queensland ........................................................................................................................................ 4 South Australia .................................................................................................................................. 6 Tasmania ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Victoria ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Western Australia .............................................................................................................................. 9 How to address Members of Parliament ........................................................................... 10 The Australian Capital Territory Ms Gai Brodtmann, MP Hon Dr Andrew Leigh, MP 205 Anketell St, Unit 8/1 Torrens St, Tuggeranong ACT, 2900 Braddon ACT, 2612 New South Wales Hon Anthony Abbott, -

Prayer Guide 2021

1 National Day of Prayer and Fasting Saturday, 27 February 2021 Welcome Welcome to the ‘House of God’ today, be that a public building, a digital zoom meeting, or any venue where you are meeting. Welcome to those who are joining us in your own church, prayer group, online through Zoom or via the webcast on YouTube/Facebook. Welcome also those who are joining us from other countries. Together in God we are making a difference! Indigenous leaders will help lead the National Day of Prayer & Fasting on Zoom between 9AM – 6PM AEDT. ZOOM ID#: 776881184 ZOOM Link: https://zoom.us/j/776881184 This is because of the many variabilities with rules regarding COVID from state to state. National leaders will contribute at the Official Prayer Zoom Service between 2PM – 3:30PM AEDT (same log-in) along with Indigenous and non-Indigenous Church Leaders. Other groups will gather in various venues mostly between 10AM – 4PM during the day. Today is a National Day of Prayer and Fasting - a day to deny ourselves and delight in God. Today is a day to glorify our FATHER in Heaven who gave His only Son that the world might be saved. JESUS the Son of the FATHER prayed for us, JESUS prayed for the Church, JESUS prayed for Jerusalem and JESUS prayed for the world. We are here to follow JESUS’ example, “Who was raised to life and who is at the right hand of God and makes intercession for us”. Romans 8:34. We are here today to pray for an outpouring of the Holy Spirit and to intercede for Australia for an awakening to the love of the FATHER and His Son JESUS, who is the radiance of the Glory of God. -

Interim Report

PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Interim Report Legal Foundations of Religious Freedom in Australia Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade November 2017 CANBERRA © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-74366-739-2 (Printed Version) ISBN 978-1-74366-740-8 (HTML Version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Chair's Foreword ..............................................................................................................................vii Membership of the Committee ........................................................................................................ix Membership of the Human Rights Sub-Committee...................................................................xiii Terms of Reference ...........................................................................................................................xv Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................xvii The Report 1 Background ...............................................................................................................1 Scope of Interim Report .........................................................................................................2 Previous work of the Committee..........................................................................................2 -

Bulletin John Iriks

The Rotary Club of Kwinana District 9465 Western Australia Chartered: 22 April 1971 Team 2020-21 President Bulletin John Iriks No 17 02nd Nov. 2020 Secretary Brian McCallum President John Rotary Club of Kwinana is in its 50th year 1971/2021 Treasurer Stephen Castelli Strange Melbourne Cup this COVID-19 year, minimal people in attendance, everybody wearing masks. Race was run, winner declared, unfortunately one of the favourites, the winner of the 2019 English Derby, Anthony Van Dyck broke down during the race and had to be euthanised. The incident was plain to see Facts & Figures during the race, disappointing that the TV broadcast never mentioned the incident until after all the presentations and speeches were over. I believe that’s now 7 horses that have died or been euthanised during cup day since 2013 Attendance this week which no doubt will give the animal activists some ammunition. Total Members 28 Apologies 7 Looking forward to the ‘Blind Wine Tasting’ social taking place Saturday night Make-up 3 at the Mulcahy’s, must be 20 years since we had the last one, good fun. Attended 19 Hon . Member LOA 2 PP Mike Nella has had an enthusiastic response to finding a home for the Lolly- Guests Run Sleigh’s, one buyer paid a good price sight unseen, another was donated Visitors 1 and picked up by the Kwinana Heritage Group. I acknowledge that many Partners residents are upset at the Lolly-Run being discontinued after such a long time. It started Christmas 1954, we arrived in Medina May 1955 so I can remember it 75.8% from the early days. -

House of Representatives - Western Australia*

House of Representatives - Western Australia* Sitting members in BOLD | *Current 1 June 2016 Labor Liberal Greens National Email Electorate Candidate Email Candidate Email candidate Email Candidate Madeleine [email protected] Craig [email protected] Dawn Jecks [email protected] Brand King g.au Buchanan l.org.au Matt [email protected] Matt Muhammad [email protected] [email protected] Burt Keogh u O'Sullivan Salman Barry Andrew [email protected] Aeron Blundell- [email protected] [email protected] Canning Winmar Hastie ov.au Camden m [email protected] Anne Aly Sheridan Young [email protected] Cowan [email protected] Luke Simpkins v.au curtinco- Melissa [email protected]. Viv Glance [email protected]. Callanan au Curtin [email protected] Julie Bishop au Carol [email protected] Ian James Durack Martin [email protected] Melissa Price v.au [email protected] Lorrae [email protected] Jill Reading [email protected] Forrest Loud [email protected] Nola Marino .au Josh http://www.pierrettekelly. [email protected]. joshforfremantle@walabor. Pierrette Kelly Kate Davis Wilson com.au/contact-pierrette/ au Fremantle org.au Bill [email protected] [email protected] Hasluck Leadbetter [email protected] Ken Wyatt u Patrick Hyslop ens.org.au Ian ian.goodenough.mp@aph. Daniel Lindley Moore Goodenough gov.au [email protected] [email protected] John John.hassell@nation Jon Ford [email protected] O'Connor [email protected] Rick Wilson u Giz Watson Hassell alswa.com Thomas Christian christian.porter.mp@aph. -

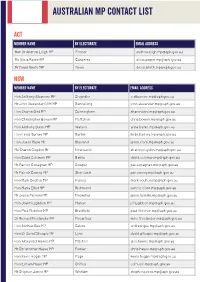

Australian Mp Contact List

AUSTRALIAN MP CONTACT LIST ACT MEMBER NAME BY ELECTORATE EMAIL ADDRESS Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP Fenner [email protected] Ms Alicia Payne MP Canberra [email protected] Mr David Smith MP Bean [email protected] NSW MEMBER NAME BY ELECTORATE EMAIL ADDRESS Hon Anthony Albanese MP Grayndler [email protected] Mr John Alexander OAM MP Bennelong [email protected] Hon Sharon Bird MP Cunningham [email protected] Hon Christopher Bowen MP McMahon [email protected] Hon Anthony Burke MP Watson [email protected] Hon Linda Burney MP Barton [email protected] Hon Jason Clare MP Blaxland [email protected] Ms Sharon Claydon MP Newcastle [email protected] Hon David Coleman MP Banks [email protected] Mr Patrick Conaghan MP Cowper [email protected] Mr Patrick Conroy MP Shortland [email protected] Hon Mark Coulton MP Parkes [email protected] Hon Maria Elliot MP Richmond [email protected] Mr Jason Falinski MP Mackellar [email protected] Hon Joel Fitzgibbon MP Hunter [email protected] Hon Paul Fletcher MP Bradfeld [email protected] Dr Michael Freelander MP Macarthur [email protected] Hon Andrew Gee MP Calare [email protected] Hon Dr David Gillespie MP Lyne [email protected] Hon Alexander Hawke MP Mitchell [email protected] Mr Christopher Hayes MP Fowler [email protected] Hon Kevin Hogan MP Page [email protected] Hon Edham Husic MP Chifey [email protected]