A Comparative Study of the Fauna Associated with Nest Mounds of Native and Introduced Populations of the Red Wood Ant Formica Paralugubris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mitochondrial Genomes of Palaeopteran Insects and Insights

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The mitochondrial genomes of palaeopteran insects and insights into the early insect relationships Nan Song1*, Xinxin Li1, Xinming Yin1, Xinghao Li1, Jian Yin2 & Pengliang Pan2 Phylogenetic relationships of basal insects remain a matter of discussion. In particular, the relationships among Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera are the focus of debate. In this study, we used a next-generation sequencing approach to reconstruct new mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from 18 species of basal insects, including six representatives of Ephemeroptera and 11 of Odonata, plus one species belonging to Zygentoma. We then compared the structures of the newly sequenced mitogenomes. A tRNA gene cluster of IMQM was found in three ephemeropteran species, which may serve as a potential synapomorphy for the family Heptageniidae. Combined with published insect mitogenome sequences, we constructed a data matrix with all 37 mitochondrial genes of 85 taxa, which had a sampling concentrating on the palaeopteran lineages. Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on various data coding schemes, using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inferences under diferent models of sequence evolution. Our results generally recovered Zygentoma as a monophyletic group, which formed a sister group to Pterygota. This confrmed the relatively primitive position of Zygentoma to Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera. Analyses using site-heterogeneous CAT-GTR model strongly supported the Palaeoptera clade, with the monophyletic Ephemeroptera being sister to the monophyletic Odonata. In addition, a sister group relationship between Palaeoptera and Neoptera was supported by the current mitogenomic data. Te acquisition of wings and of ability of fight contribute to the success of insects in the planet. -

Comparison of Sporormiella Dung Fungal Spores and Oribatid Mites As Indicators of Large Herbivore Presence: Evidence from the Cuzco Region of Peru

Comparison of Sporormiella dung fungal spores and oribatid mites as indicators of large herbivore presence: evidence from the Cuzco region of Peru Article (Accepted Version) Chepstow-Lusty, Alexander, Frogley, Michael and Baker, Anne (2019) Comparison of Sporormiella dung fungal spores and oribatid mites as indicators of large herbivore presence: evidence from the Cuzco region of Peru. Journal of Archaeological Science. ISSN 0305-4403 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/80870/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

In Termite Nests (Blattodea: Termitidae) in a Cocoa Plantation in Brazil Biota Neotropica, Vol

Biota Neotropica ISSN: 1676-0611 [email protected] Instituto Virtual da Biodiversidade Brasil Teixeira Lisboa, Jonathas; Guerreiro Couto, Erminda da Conceição; Pereira Santos, Pollyanna; Charles Delabie, Jacques Hubert; Araujo, Paula Beatriz Terrestrial isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) in termite nests (Blattodea: Termitidae) in a cocoa plantation in Brazil Biota Neotropica, vol. 13, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2013, pp. 393-397 Instituto Virtual da Biodiversidade Campinas, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199128991039 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Biota Neotrop., vol. 13, no. 3 Terrestrial isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) in termite nests (Blattodea: Termitidae) in a cocoa plantation in Brazil Jonathas Teixeira Lisboa1,7, Erminda da Conceição Guerreiro Couto2, Pollyanna Pereira Santos3, Jacques Hubert Charles Delabie4,5 & Paula Beatriz Araujo6 1Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz – UESC, Campus Soane Nazaré de Andrade, Rod. Ilhéus-Itabuna, km 16, CEP 45662-900, Ilhéus, BA, Brasil. www.uesc.br/zoologia 2Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz – UESC, Campus Soane Nazaré de Andrade, Rod. Ilhéus-Itabuna, km 16, CEP 45662-900, Ilhéus, BA, Brasil. www.uesc.br/cursos/pos_graduacao/mestrado/ppsat 3Universidade Federal de Viçosa – UFV, CEP 36570-000 Viçosa, MG, Brasil. www.pos.entomologia.ufv.br 4Departamento de Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz – UESC, Campus Soane Nazaré de Andrade, Rod. Ilhéus-Itabuna, km 16, CEP 45662-900, Ilhéus, BA, Brasil. www.uesc.br/dcaa/index.php 5Laboratório de Mirmecologia, Convênio UESC/CEPLAC, Centro de Pesquisa do Cacau, CP 7, CEP 45600-000 Itabuna, BA, Brasil. -

Ecology of Soil Microarthropods in Gobi Gurvan Saykhan Mountains, Southern Mongolia Tsedev Bolortuya National University of Mongolia

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2005 Ecology of Soil Microarthropods in Gobi Gurvan Saykhan Mountains, Southern Mongolia Tsedev Bolortuya National University of Mongolia Badamdorj Bayartogtokh National University of Mongolia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Desert Ecology Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Bolortuya, Tsedev and Bayartogtokh, Badamdorj, "Ecology of Soil Microarthropods in Gobi Gurvan Saykhan Mountains, Southern Mongolia" (2005). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 120. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. In: Proceedings of the symposium ”Ecosystem Research in the Arid Environments of Central Asia: Results, Challenges, and Perspectives,” Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, June 23-24, 2004. Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei (2005) 5. Copyright 2005, Martin-Luther-Universität. Used by permission. Erforsch. biol. Ress. Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 2005 (9): 53–58 Ecology of soil microarthropods in Gobi Gurvan Saykhan mountains, southern Mongolia Ts. -

The Canopy Arthropods of Old and Mature Pine Pinus Sylvestris in Norway

ECOGRAPHY 26: 490–502, 2003 The canopy arthropods of old and mature pine Pinus syl7estris in Norway Karl H. Thunes, John Skarveit and Ivar Gjerde Thunes, K. H., Skarveit, J. and Gjerde, I. 2003. The canopy arthropods of old and mature pine Pinus syl6estris in Norway. – Ecography 26: 490–502. We fogged 24 trees in two pine dominated forests in Norway with a synthetic pyrethroid in order to compare the canopy-dwelling fauna of arthropods between costal (Kvam) and boreal (Sigdal) sites and between old (250–330 yr) and mature (60–120 yr) trees at Sigdal. Almost 30 000 specimens were assigned to 510 species; only 93 species were present at both sites. Species diversity, as established by rarefaction, was similar in old and mature trees. However, the number of species new to Norway (including nine species new to science) was significantly higher in the old trees. We suggest that the scarcity of old trees, habitat heterogeneity and structural differences between old and mature trees may explain these patterns. Productivity and topographic position at the site of growth explained the between-tree variation in species occurrence for the more abundant species, which were mainly Collembola and Oribatida. Species diversity was similar at the boreal and coastal sites, but there were clear differences in species composition. K. H. Thunes ([email protected]) and I. Gjerde, Norwegian Forest Research Inst., Fanaflaten 4, N-5244 Fana, Norway.–J. Skart6eit, Museum of Zoology, Uni6. of Bergen, Muse´plass 3, N-5007 Bergen, Norway, (present address: Dept of Ecology and Conser6ation, Scottish Agricultural College, Ayr Campus, Auchincrui6e Estate, Ayr, Scotland KA65HW. -

The Armoured Mite Fauna (Acari: Oribatida) from a Long-Term Study in the Scots Pine Forest of the Northern Vidzeme Biosphere Reserve, Latvia

FRAGMENTA FAUNISTICA 57 (2): 141–149, 2014 PL ISSN 0015-9301 © MUSEUM AND INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY PAS DOI 10.3161/00159301FF2014.57.2.141 The armoured mite fauna (Acari: Oribatida) from a long-term study in the Scots pine forest of the Northern Vidzeme Biosphere Reserve, Latvia 1 2 1 Uģis KAGAINIS , Voldemārs SPUNĢIS and Viesturs MELECIS 1 Institute of Biology, University of Latvia, 3 Miera Street, LV-2169, Salaspils, Latvia; e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) 2 Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, Faculty of Biology,University of Latvia, 4 Kronvalda Blvd., LV-1586, Riga, Latvia; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In 1992–2012, a considerable amount of soil micro-arthropods has been collected annually as a part of a project of the National Long-Term Ecological Research Network of Latvia at the Mazsalaca Scots Pine forest sites of the North Vidzeme Biosphere Reserve. Until now, the data on oribatid species have not been published. This paper presents a list of oribatid species collected during 21 years of ongoing research in three pine stands of different age. The faunistic records refer to 84 species (including 17 species new to the fauna of Latvia), 1 subspecies, 1 form, 5 morphospecies and 18 unidentified taxa. The most dominant and most frequent oribatid species are Oppiella (Oppiella) nova, Tectocepheus velatus velatus and Suctobelbella falcata. Key words: species list, fauna, stand-age, LTER, Mazsalaca INTRODUCTION Most studies of Oribatida or the so-called armoured mites (Subías 2004) have been relatively short term and/or from different ecosystems simultaneously and do not show long- term changes (Winter et al. -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a Coastal Plain Area in the State of Paraná, Brazil

62 TROP. LEPID. RES., 26(2): 62-67, 2016 LEVISKI ET AL.: Butterflies in Paraná Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a coastal plain area in the state of Paraná, Brazil Gabriela Lourenço Leviski¹*, Luziany Queiroz-Santos¹, Ricardo Russo Siewert¹, Lucy Mila Garcia Salik¹, Mirna Martins Casagrande¹ and Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke¹ ¹ Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]٭ Abstract: The coastal plain environments of southern Brazil are neglected and poorly represented in Conservation Units. In view of the importance of sampling these areas, the present study conducted the first butterfly inventory of a coastal area in the state of Paraná. Samples were taken in the Floresta Estadual do Palmito, from February 2014 through January 2015, using insect nets and traps for fruit-feeding butterfly species. A total of 200 species were recorded, in the families Hesperiidae (77), Nymphalidae (73), Riodinidae (20), Lycaenidae (19), Pieridae (7) and Papilionidae (4). Particularly notable records included the rare and vulnerable Pseudotinea hemis (Schaus, 1927), representing the lowest elevation record for this species, and Temenis huebneri korallion Fruhstorfer, 1912, a new record for Paraná. These results reinforce the need to direct sampling efforts to poorly inventoried areas, to increase knowledge of the distribution and occurrence patterns of butterflies in Brazil. Key words: Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, conservation, inventory, species richness. INTRODUCTION the importance of inventories to knowledge of the fauna and its conservation, the present study inventoried the species of Faunal inventories are important for providing knowledge butterflies of the Floresta Estadual do Palmito. -

Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska

Zootaxa 4666 (1): 001–180 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4666.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BA01E30E-7F64-49AB-910A-7EE6E597A4A4 ZOOTAXA 4666 Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER1,3 & ZOË LINDO1 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A0C6, Canada. 2Department of Biology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by T. Pfingstl: 26 Jul. 2019; published: 6 Sept. 2019 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 VALERIE M. BEHAN-PELLETIER & ZOË LINDO Checklist of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Canada and Alaska (Zootaxa 4666) 180 pp.; 30 cm. 6 Sept. 2019 ISBN 978-1-77670-761-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-762-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2019 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] https://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 4666 (1) © 2019 Magnolia Press BEHAN-PELLETIER & LINDO Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................5 -

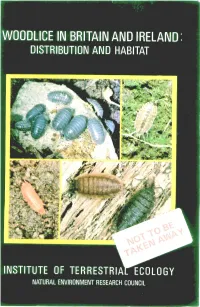

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 78 (30-06-2015): 1–12. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Clase: Malacostraca Orden ISOPODA: Oniscidea Manual CLASE MALACOSTRACA Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea Lluc Garcia *Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals, Sóller, Mallorca (Illes Balears) Imagen superior: Oniscus asellus. Fotografía LL. Garcia 1. Breve definición del grupo y principales caracteres diagnósticos 1.1. Morfología. Generalidades. Los isópodos terrestres (Oniscidea) son crustáceos eumalacostráceos pertenecientes al orden Isopoda, aunque reúnen una serie de características morfológicas y fisiológicas relacionadas con su modo de vida terrestre que permiten considerarlos como un grupo natural bien definido, considerado actualmente como monofilético (Schmidt, 2002, 2003, 2008). Como todos los representantes del orden, su cuerpo está dor- soventralmente aplanado y se divide en tres partes bien diferenciables a simple vista: 1. El céfalon, en el que sitúan los ojos, en la mayoría de los casos compuestos; dos pares de ante- nas; y el aparato masticador con un par de mandíbulas, que son asimétricas, y dos pares de maxilas. En los isópodos terrestres el céfalon está compuesto por la cabeza propiamente dicha y por el primer seg- mento del pereion, soldado a ésta y llamado también segmento maxilipedal por insertarse en él los maxilí- pedos, que cubren el resto de piezas bucales. La división entre este segmento y el resto de la cabeza es invisible en vista dorsal en la gran mayoría de isópodos terrestres aunque sí que es apreciable en forma surcos laterales que lo separan de la región cefálica. Por eso se debe considerar más propiamente como un cefalotórax. -

Hotspots of Mite New Species Discovery: Sarcoptiformes (2013–2015)

Zootaxa 4208 (2): 101–126 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Editorial ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4208.2.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47690FBF-B745-4A65-8887-AADFF1189719 Hotspots of mite new species discovery: Sarcoptiformes (2013–2015) GUANG-YUN LI1 & ZHI-QIANG ZHANG1,2 1 School of Biological Sciences, the University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2 Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, Auckland, New Zealand; corresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract A list of of type localities and depositories of new species of the mite order Sarciptiformes published in two journals (Zootaxa and Systematic & Applied Acarology) during 2013–2015 is presented in this paper, and trends and patterns of new species are summarised. The 242 new species are distributed unevenly among 50 families, with 62% of the total from the top 10 families. Geographically, these species are distributed unevenly among 39 countries. Most new species (72%) are from the top 10 countries, whereas 61% of the countries have only 1–3 new species each. Four of the top 10 countries are from Asia (Vietnam, China, India and The Philippines). Key words: Acari, Sarcoptiformes, new species, distribution, type locality, type depository Introduction This paper provides a list of the type localities and depositories of new species of the order Sarciptiformes (Acari: Acariformes) published in two journals (Zootaxa and Systematic & Applied Acarology (SAA)) during 2013–2015 and a summary of trends and patterns of these new species. It is a continuation of a previous paper (Liu et al. -

Ctenolepisma Longicaudata (Zygentoma: Lepismatidae) New to Britain

CTENOLEPISMA LONGICAUDATA (ZYGENTOMA: LEPISMATIDAE) NEW TO BRITAIN Article Published Version Goddard, M., Foster, C. and Holloway, G. (2016) CTENOLEPISMA LONGICAUDATA (ZYGENTOMA: LEPISMATIDAE) NEW TO BRITAIN. Journal of the British Entomological and Natural History Society, 29. pp. 33-36. Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/85586/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: British Entomological and natural History Society All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online BR. J. ENT. NAT. HIST., 29: 2016 33 CTENOLEPISMA LONGICAUDATA (ZYGENTOMA: LEPISMATIDAE) NEW TO BRITAIN M. R. GODDARD,C.W.FOSTER &G.J.HOLLOWAY Centre for Wildlife Assessment and Conservation, School of Biological Sciences, Harborne Building, The University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, Berkshire RG6 2AS. email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudata Escherich 1905 is reported for the first time in Britain, from Whitley Wood, Reading, Berkshire (VC22). This addition increases the number of British species of the order Zygentoma from two to three, all in the family Lepismatidae. INTRODUCTION Silverfish, firebrats and bristletails were formerly grouped in a single order, the Thysanura (Delany, 1954), but silverfish and firebrats are now recognized as belonging to a separate order, the Zygentoma (Barnard, 2011).