G.R. No. 212426 - RENE A.V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MW Voltaire T. Gazmin Grand Master of Masons, MY 2016-2017 the Cable Tow Vol

Special Issue • Our New Grand Master • Grand Lodge Theme for the Year • Plans and Programs • GLP Schedule 2016- 2017 • Masonic Education • The events and Activities of Ancom 2016 • Our New Junior Grand Warden: RW Agapito Suan, Jr. • The new GLP officers and appointees MW Voltaire T. Gazmin Grand Master of Masons, MY 2016-2017 The Cable Tow Vol. 93 Special Issue No. 1 Editor’s Notes In the service of one’s Grand Mother DURING THE GRAND MASTER’S GALA held at the Taal Vista Hotel last April 30, then newly-installed MW Voltaire Gazmin in a hushed voice uttered one of his very first directives as a Grand Master: Let’s come out with a special AnCom issue of The Cable Tow or ELSE! THE LAST TWO WORDS, OF COURSE, IS A across our country’s archipelago and at the same time JOKE! be prompt in the delivery of news and information so needed for the sustenance of the growing craftsman. But our beloved Grand Master did ask for a May issue of the Cable Tow and so he shall have it. Indeed, just as what the Grand Orient directs and as far as Volume 93 is concerned, this publication will This is a special issue of The Cable Tow, which aim to Personify Freemasonry by thinking, writing encases within its pages the events and highlights and publishing articles the Mason’s Way. of the 100th Annual Communications of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted With most of the result of the recent national elections Masons of the Philippines. -

Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: the Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, Phd, and Walter Lohman

BACKGROUNDER No. 2733 | SEptEMBER 24, 2012 Getting the Philippines Air Force Flying Again: The Role of the U.S.–Philippines Alliance Renato Cruz De Castro, PhD, and Walter Lohman Abstract or two years, the U.S.– The recent standoff at Scarborough FPhilippines alliance has been Key Points Shoal between the Philippines and challenged in ways unseen since the China demonstrates how Beijing is closure of two American bases on ■■ The U.S. needs a fully capable ally targeting Manila in its strategy of Filipino territory in the early 1990s.1 in the South China Sea to protect U.S.–Philippines interests. maritime brinkmanship. Manila’s China’s aggressive, well-resourced weakness stems from the Philippine pursuit of its territorial claims in ■■ The Philippines Air Force is in a Air Force’s (PAF) lack of air- the South China Sea has brought a deplorable state—it does not have defense system and air-surveillance thousand nautical miles from its the capability to effectively moni- tor, let alone defend, Philippine capabilities to patrol and protect own shores, and very close to the airspace. Philippine airspace and maritime Philippines. ■■ territory. The PAF’s deplorable state For the Philippines, sovereignty, The Philippines has no fighter jets. As a result, it also lacks trained is attributed to the Armed Forces access to energy, and fishing grounds fighter pilots, logistics training, of the Philippines’ single-minded are at stake. For the U.S., its role as and associated basing facilities. focus on internal security since 2001. regional guarantor of peace, secu- ■■ The government of the Philippines Currently, the Aquino administration rity, and freedom of the seas is being is engaged in a serious effort to is undertaking a major reform challenged—as well as its reliability more fully resource its military to shift the PAF from its focus on as an ally. -

Philippines Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Philippines Country Report Status Index 1-10 6.53 # 38 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 6.70 # 40 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 6.36 # 40 of 129 Management Index 1-10 5.22 # 57 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Philippines Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Philippines 2 Key Indicators Population M 99.1 HDI 0.660 GDP p.c., PPP $ 6982.4 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.6 HDI rank of 187 117 Gini Index 43.0 Life expectancy years 68.7 UN Education Index 0.610 Poverty3 % 37.6 Urban population % 44.5 Gender inequality2 0.406 Aid per capita $ 1.9 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary In the last two years, the quality of democracy in the Philippines has stagnated or even slightly deteriorated. The Aquino administration which had raised a great deal of hope for a reinvigoration of democracy has not achieved this target, but rather got entangled in homemade political difficulties, particularly in 2014. -

37402-012: Technical Assistance Consultant's Report

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 37402 December 2013 RETA 6143: Technical Assistance for Promoting Gender Equality and Women Empowerment (Financed by the Gender and Development Cooperation Fund) Prepared by LAND EQUITY INTERNATIONAL PTY, LTD. (LEI) Australia This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Promoting Gender Equality in Land Access and Land Tenure Security in the Philippines Brenda Batistiana Land Equity International, Pty. Ltd. (LEI), in association with the Land Equity Technology Services (LETS) RETA 6143: Promoting Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Bureau of Local Government Finance (BLGF) of the Department of Finance (DOF) through the Support of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) December 2013 Promoting Gender Equality in Land Access and Land Tenure Security 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 8 I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ -

Comparative Connections a Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations US-Southeast Asia Relations: Philippines – An Exemplar of the US Rebalance Sheldon Simon Arizona State University The Philippines under President Benigno Aquino III has linked its military modernization and overall external defense to the US rebalance. Washington has raised its annual military assistance by two-thirds to $50 million and is providing surplus military equipment. To further cement the relationship, Philippine and US defense officials announced that the two countries would negotiate a new “framework agreement” under the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty providing for greater access by US forces to Philippine bases and the positioning of equipment at these facilities. Washington is also stepping up participation in ASEAN-based security organizations, sending forces in June to an 18-nation ASEAN Defense Ministers Plus exercise covering military medicine and humanitarian assistance in Brunei. A July visit to Washington by Vietnam’s President Truong Tan Sang resulted in a US-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership, actually seen as a step below the Strategic Partnerships Hanoi has negotiated with several other countries. Myanmar’s president came to Washington in May, the first visit by the country’s head of state since 1966. An economic agreement was the chief deliverable. While President Obama praised Myanmar’s democratic progress, he also expressed concern about increased sectarian violence that the government seems unable (or unwilling) to bring under control. The rebalance and the Philippines While the Obama administration’s foreign and defense policies’ rebalance to Asia is portrayed as a “whole of government” endeavor, involving civilian as well as security agencies, its military components have received the most attention, especially in Southeast Asia. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

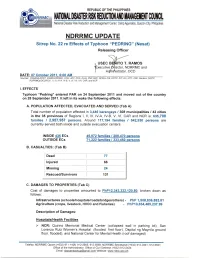

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 22 Re Effects of Typhoon PEDRING

Region I: La Paz Community and Medicare Hospital (flooded and non functional) Region II: Southern Isabela General Hospital roofs of Billing sections and Office removed Region III: RHU I of Paombong (roof damaged), Calumpit District Hospital (flooded) and Hagonoy District Hospital (flooded and non functional) Cost of damages on health facilities (infrastructure and equipment) is still being validated by DOH Infrastructure Region III Collapsed Dikes and Creeks in Pampanga - Brgy. Mandili Dike, Brgy. Barangca Dike in Candaba, Matubig Creek, San Jose Dayat Creek, San Juan Gandara, San Agustin Sapang Maragol in Guagua earthdike - (breached) and Brgy. Gatud and Dampe earthdike in Floridablanca - collapsed; slope protection in Brgy. San Pedro Purok 1 (100 m); slope protection in Brgy. Benedicto Purok 1 (300 m); Slope protection in Brgy. Valdez along Gumain River (200 M); and Brgy. Solib Purok 6, Porac River and River dike in Sto. Cristo, Sta. Rosa, Sta. Rita and Sta. Catalina, Lubao, Pampanga. D. DAMAGED HOUSES (Tab D) A total of 51,502 houses were damaged in Regions I, II, III, IV-A, IV-B, V, VI, and CAR (6,825 totally and 44,677 partially) E. STATUS OF LIFELINES: 1. ROADS AND BRIDGES CONDITION (Tab E) A total of 29 bridges/road sections were reported impassable in Region I (1), Region II (7), Region III (13), and CAR (8). F. STATUS OF DAMS (As of 4:00 PM, 06 October 2011) The following dams opened their respective gates as the water levels have reached their spilling levels: Ambuklao (3 Gates / 1.5 m); Binga (2 Gates / 2 m); Magat (1 Gate / 2 m); and San Roque (2 Gates / 1 m) G. -

Southern Philippines, February 2011

Confirms CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Southern Philippines, February 2011 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by nationals from the southern Philippines, specifically Mindanao, Tawi Tawi, Basilan and Sulu. This report covers events up to 28 February 2011. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

GI COME BACK: America's Return to the Philippines by Felix K. Chang

October 2013 GI COME BACK: America’s Return to the Philippines By Felix K. Chang Felix K. Chang is an FPRI Senior Fellow, as well as the co-founder of Avenir Bold, a venture consultancy. He was previously a consultant in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Strategy and Organization practice; among his clients were the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and other agencies. Earlier, he served as a senior planner and an intelligence officer in the U.S. Department of Defense and a business advisor at Mobil Oil Corporation, where he dealt with strategic planning for upstream and midstream investments throughout Asia and Africa. His publications include articles in American Interest, National Interest, Orbis, and Parameters. For his previous FPRI essays, see: http://www.fpri.org/contributors/felix-chang “This is not primarily a military relationship” answered the U.S. ambassador in Manila when asked about the relations between the Philippines and the United States. Perhaps not, but its military aspects have certainly gained greater prominence in recent years. Indeed, ahead of President Barack Obama’s originally planned visit to Manila in October 2013, both countries were working on a new security accord, called the Increased Rotational Presence (IRP) Agreement. Once in effect, it would allow American forces to more regularly rotate through the island country for joint U.S.-Philippine military exercises, focusing on maritime security, maritime domain awareness, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. The new agreement would also allow the United States to preposition the combat equipment used by its forces at Philippine military bases. -

Philippines National Conference February 2-4, 2015 Crowne Plaza

11th Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) Philippines National Conference February 2-4, 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ortigas Ave.Corner ADB Ave., Quezon City, Philippines “Transforming Communities Through More Responsive National and Local Budgets” CONFERENCE PROGRAM As of January 31, 2015 February 2, 2015 MORNING SESSION Session 1 Opening Ceremony 8:30 Invocation/National Anthem 8:35 Welcome Remarks Dr. Tereso S. Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI 8:40 Introduction of Speakers 8:45 Opening Message Br. Jose Mari Jimenez, FSC President and Sector Leader De La Salle Philippines 8:55 Community Based Monitoring System (CBMS): Overview Dr. Celia M. Reyes CBMS International Network Coordinating Team Leader PEP Asia-CBMS Network Office, DLSU 9:15 Introduction of Keynote Speaker Bottom Up Budgeting: Making the Budget More Responsive to Local Needs 9:20 Secretary Florencio Abad Department of Budget and Management 9:50-10:40 Panel Discussion on Bottom Up Budgeting Secretary Florencio Abad, DBM Governor Alfonso Umali Jr., ULAP Dir. Anna Liza Bonagua, DILG Moderator: Dr. Tereso S. Tullao, Jr. Director, DLSU-AKI 10:40 – 11:00 COFFEE BREAK Page 1 of 9 11th Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) Philippines National Conference February 2-4, 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ortigas Ave.Corner ADB Ave., Quezon City, Philippines “Transforming Communities Through More Responsive National and Local Budgets” CONFERENCE PROGRAM As of January 31, 2015 Session 2 CBMS Accelerated Poverty Profiling (APP) and new applications on Providing Social Protection and Job Generation 11:00 Session Overview/Introduction of Speakers Chair: Dr. Augusto Rodriguez Chief of the Social Policy Section, UNICEF Philippines 11:10 Presentation 1. -

REFORMS: What Have We Achieved?

REFORMS: What Have We Achieved? Restoring people’s trust in government and democratic PAMANA, an inter-agency project led by the Office To incentivize LGUs in setting transparency and institutions, effective and adequate social services and of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process accountability standards, the Performance economic opportunity, and strengthening the (OPAPP), is set up to end the long-standing Challenge Fund was institutionalized. It provides constituencies for reform are the Aquino conflict in the country by building peaceful incentives to Administration’s key objectives as it pursues genuine communities in 1,921 conflict-affected barangays LGUs as a way of recognizing good performance reform in government. So far, significant victories have in 171 municipalities, in 34 provinces. in internal housekeeping, and in the alignment of been achieved, particularly in the areas of anti- local development investment programs with corruption, the peace process, and local governance. national development goals. Many reform advocates acknowledge these gains, and Through the All-Out-War, All-Out-Peace, All-Out- are calling for the needed institutional-legal support Justice Policy of PNoy, the government extends Similarly, the Seal of Good Housekeeping for Local and transformational leadership that can keep the ball Governments is awarded to LGUs that promote the work for peace by bringing to justice rolling so to speak even beyond 2016. and practice openness, transparency, and perpetrators of atrocities. President Aquino accountability. Local legislation, development What has been achieved so far? The following announced the pursuit of “all-out justice” in planning, resource generation, resource allocation provides general description of these reforms. -

AFPPS Starts 2015 with New Electronic Information Management System

Vol. 1 No. 6 • November-December 2014 IN LINE WITH AFP TRANSFORMATION ROADMAP, ISO CERTIFICATION UPDATE ON ISO CERTIFICATION INITIATIVES AFPPS starts 2015 with AFPPS undergoes Management Review Inching closer to ISO 9001:2008 new electronic information Certification, the AFP Procurement Service conducted Management Review –the third to the last three major activities towards the management system Service’s goal to finally be certified as ISO 9001:2008 compliant. he AFP Procurement Office (CO), which developed the project, In his report to AFP Chief of Staff Gen Service (AFPPS) is and at the General Headquarters Gregorio Pio Catapang Jr, AFPPS Commander literally starting Procurement Center Col Alvin Francis A Javier PA (GSC) stated that 2015 with a bang with its (GHQPC). the Service has already accomplished 85 percent parallel testing of He stressed that of the scheduled activities for certification. the Procurement the development of the The Management Review –which Information Management system is in line with will be followed by Final Preparation System (PIMS), an electronic the AFP Transformation for Certification and the Third Party T Certification, was held last November 28. monitoring and information Roadmap and the AFPPS’ Col Javier said that the Service is targeting system project, in two of its initiatives towards ISO to execute all the scheduled activities by units based at Camp General 9001:2008 Certification. end of January 2015 as it aims to obtain ISO Emilio Aguinaldo and Fort San Felipe, If proven effective and responsive, the 9001:2008 Certification by March. Cavite City on the first week of January. system will be used in all Procurement “We have worked so hard to come this Col Alvin Francis A Javier PA (GSC), Centers (PCs) and Contracting Offices far, and now that we are closer to achieving Commander of AFPPS, said that the system (COs) nationwide.