Music As a Prior Condition to Task Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAROLS for CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter

Gerald Neufeld conductor Alison MacNeill accompanist CAROLS FOR CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter Sunday November 30, 2014 WINTER’S EVE TRIO St. George’s Anglican Church | 3:00 pm Sharlene Wallace Harp Joe Macerollo Accordion George Koller Bass concert sponsors soloist sponsors government & community support Program CAROLS FOR CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter Hodie . Gregorian Chant Wolcum Yole, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Herself a rose, who bore the Rose . Christina Rossetti Laurie McDonald, reader As dew in Aprille, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Birth of Jesus . Luke 2, 1–20 Scott Worsfold, reader This little Babe, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Interlude, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Greensleeves . .. Traditional Winter’s Eve Trio What Child is this . arr . John Stainer Winter’s Eve Trio, choir and audience 1. What child is this, who laid to rest 2. Why lies He in such mean estate, On Mary’s lap is sleeping? Where ox and ass are feeding? Whom angels greet with anthem sweet, Good Christian, fear: for sinners here While shepherds watch are keeping? The silent Word is pleading; This, this is Christ, the King; Nails, spear shall pierce Him through, Whom shepherds guard and angels sing; The Cross be born for me, for you; Haste, haste to bring Him laud, Hail, hail the Word made flesh, The Babe, the Son of Mary! The Babe, the Son of Mary! 3. So bring Him incense, gold, and myrrh, Come peasant, king to own Him; The King of kings salvation brings; Let loving hearts enthrone Him. -

Harp Seattle 2018 Booklet WEB ONLY.Pub

General Information for HARP SEATTLE 2018 About Harp Seattle Rental Harps Harp Seattle is a three-day festival at Dusty Strings Music Once you register, you can indicate on your registration Store & School in Seattle, WA for harpers of all levels to form if you would like to rent a harp, and if so, what kind. participate in an event that has been part of the folk harp We will contact you a month before the event to set up community for over a decade. Seasoned performers pre- your rental. Availability is first-come-first-served. sent workshops created to enhance the skills and knowledge of players at all levels so there’s something for everyone. Refund Policy You may cancel your registration for a full refund less a Location $25 administrative fee through September 5 th , 2018. You All workshops, concerts, and happenings take place at may cancel your registration for a 50% refund less a $25 Dusty Strings Music Store & School, 3406 Fremont Avenue administrative fee through October 1 st , 2016. No refunds N, Seattle, except for the tour of the manufacturing facility, are available for partial attendance or for cancellations which is located at 3450 16 th Avenue W in the Interbay made after October 1 st . All workshops, presenters, and neighborhood. See page 12 for directions and parking times are subject to change. information for both locations. Harp Valet Registration Harp valets are ready to assist you with dropping off your Registration includes an all-access pass to the weekend’s harp on Friday morning, October 5 th and picking it up on workshops, concerts, and happenings. -

Concert & Dance Listings • Cd Reviews • Free Events

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS • FREE EVENTS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 4 Number 6 Nov-Dec 2004 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers Music and Poetry Quench the Thirst of Our Soul FESTIVAL IN THE DESERT BY ENRICO DEL ZOTTO usic and poetry rarely cross paths with war. For desert dwellers, poetry has long been another way of making war, just as their sword dances are a choreographic represen- M tation of real conflict. Just as the mastery of insideinside thisthis issue:issue: space and territory has always depended on the control of wells and water resources, words have been constantly fed and nourished with metaphors SomeThe Thoughts Cradle onof and elegies. It’s as if life in this desolate immensity forces you to quench two thirsts rather than one; that of the body and that KoreanCante Folk Flamenco Music of the soul. The Annual Festival in the Desert quenches our thirst of the spirit…Francis Dordor The Los Angeles The annual Festival in the Desert has been held on the edge Put On Your of the Sahara in Mali since January 2001. Based on the tradi- tional gatherings of the Touareg (or Tuareg) people of Mali, KlezmerDancing SceneShoes this 3-day event brings together participants from not only the Tuareg tradition, but from throughout Africa and the world. Past performers have included Habib Koité, Manu Chao, Robert Plant, Ali Farka Toure, and Blackfire, a Navajo band PLUS:PLUS: from Arizona. -

The Music Center's Study Guide to the Performing Arts

MUSIC TRADITIONAL ARTISTIC PROCESSES ® CLASSICAL 1. CREATING (Cr) Artsource CONTEMPORARY 2. PERFORMING, PRESENTING, PRODUCING (Pr) The Music Center’s Study Guide to the Performing Arts EXPERIMENTAL 3. RESPONDING (Re) MULTI-MEDIA 4. CONNECTING (Cn) ENDURING FREEDOM & THE POWER THE HUMAN TRANSFORMATION VALUES OPPRESSION OF NATURE FAMILY Title of Work: About the Artwork: Joropo Azul and Zayante, Paraguayan Folk Harp The audio selection is really a pairing of two Creator: Alfredo Rolando Ortiz contrasting pieces. Joropo Azul and Zayante are two short works, representing traditional styles with both Background Information: classical and folk roots from Latin America. The “I was born in Cuba where the harp is not a traditional pieces were originally improvised and then become instrument. My adventure with the harp began when I was totally new compositions. The first piece, Joropo Azul, 11 years old. Our family emigrated to Venezuela. As the is in the style of joropo, the national folk dance of ship neared land, I saw green forms rising up through the Venezuela. It is set in contrast with Zayante, clouds, and soon the mountains of Venezuela loomed in composed in the traditional style of Paraguay. Joropo front of us. As we drove up that mountain there was this Azul is played in a major key, with very bright tones beautiful music on the radio. I didn’t know what it was, but and an upbeat rhythm. The melody sometimes I fell in love with it.” It was a harp! As a teenager, Alfredo follows the main beat and sometimes is heard off the Ortiz borrowed one and began taking lessons from a fellow beat (syncopated), which gives a complex texture to student. -

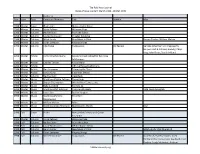

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998 Author or Year Issue Type Composer/Arranger Title Subtitle Misc 1998 Winter Cover Illustration Make a Joyful Noise 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Winter Column Laurie Rasmussen Chapter Roundup 1998 Winter Column Mitch Landy New Music in Print Harper Tasche; William Mahan 1998 Winter Column Dinah LeHoven Ringing Strings 1998 Winter Column Alys Howe Harpsounds CD Review Verlene Schermer; Lori Pappajohn; Harpers Hall & Culinary Society; Chrys King; John Doan; David Helfand 1998 Winter Article Patty Anne McAdams Second annual retreat for Bay Area folk harpers 1998 Winter Article Charles Tanner A Cool Harp! 1998 Winter Article Fifth Gulf Coast Celtic harp 1998 Winter Article Ann Heymann Trimming the Tune 1998 Winter Article James Kurtz Electronic Effects 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn Classifieds 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Sylvia Fellows Three Kings 1998 Winter Music Sharon Thormahlen Where River Turns to sky 1998 Winter Music Reba Lunsford Tootie's Jig 1998 Winter Music Traditional/M. Schroyer The Friendly Beats 12th Century English 1998 Winter Music Joyce Rice By Yon Yangtze 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Serena He is Born Underwood 1998 Winter Music William Mahan Adios 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Ann Heymann MacDonald's March Irish 1998 Fall Cover Photo New Zealand's Harp and Guitar Ensemble 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Fall Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Fall Column -

Harp Syllabus Message from the President 3 Preface

Harp The Royal Conservatory of Music Official Examination Syllabus © Copyright 2009 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-55440-252-6 20 19 18 17 16 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Contents Message from the President ................ 3 www.rcmexaminations.org ................. 4 Preface................................. 4 About Us............................... 5 REGISTER FOR AN EXAMINATION Examination Sessions and Registration Deadlines . 7 Examination Centers ..................... 7 Online Registration . 7 Examination Scheduling ................... 8 Examination Fees ........................ 7 EXAMINATION REGULATIONS Examination Procedures ................... 9 Practical Examination Certificates ............ 15 Credits and Refunds for Missed Examinations .... 9 School Credits........................... 16 Candidates with Special Needs .............. 10 Medals ................................ 16 Examination Results ...................... 10 RESPs ................................. 16 Table of Marks ......................... 11 Examination Repertoire . 17 Theory Examinations ..................... 11 Substitutions ............................ 19 ARCT Examinations ...................... 14 Abbreviations ........................... 20 Supplemental Examinations ................ 14 Thematic Catalogs........................ 21 Musicianship Examinations ................ 15 GRADE-BY-GRADE REQUIREMENTS Technical Requirements.................... 22 Grade 9 ............................... 55 Grade 2 .............................. -

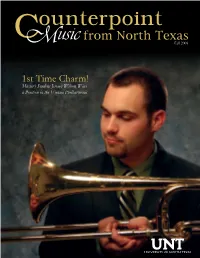

1St Time Charm! Master’S Student Jeremy Wilson Wins a Position in the Vienna Philharmonic Fortepiano

Fall 2008 1st Time Charm! Master’s Student Jeremy Wilson Wins a Position in the Vienna Philharmonic Fortepiano Exciting Acquisition— a First for the College of Music rriving in spring 2007 from the McNulty workshop in the Czech Republic, this gorgeous fortepiano, an 1805 Walter und Sohn copy, Ahas already become an important educational and performance tool within the College of Music. Many, many thanks are due to Professor Emeritus Michael Collins, philanthropist Paul Voertman and the National Endowment for the Arts for their generosity that enabled us to purchase this instrument. One of its most interesting uses has been the recording project planned in conjunction with an upcoming book by UNT musicology alumnus James “Chip” Parsons, Professor of Music at Missouri State University and a former student of Professor Collins. A-R Editions will publish Dr. Parsons’ book on early alternate settings of Schiller’s poem “An die Freude” (heard in the famous last movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony). The accompanying CD, coordinated by UNT faculty Elvia Puccinelli, will include selections based on the facsimile scores included in the book. (For more about the fortepiano and its impact, go to page 17.) Contents Dean’s Message ......................................................4 William W. “Bill” Winspear Transitions ................................................................6 1933-2007 Welcome to New Faculty ..........................................8 International Relationships .......................................11 illiam W. “Bill” -

Mnprogrambook.Pdf

AMERICAN HARP SOCIETY 35th National Conference Macalester College St. Paul, Minnesota June 19-22, 2002 1 AHS National Conference AMERICAN HARP SOCIETY Marcel Grandjany, Chairman, Founding Committee Anne Adams Awards Auditions Lucy Clark Scandrett President Elizabeth Richter Karen Lindquist Vice-Presidents Ruth Papalia Secretary Jan Jennings Treasurer Jan Bishop Chairman of the Board THIRTY-FIFTH NATIONAL CONFERENCE Macalester College St. Paul, Minnesota June 19-22, 2002 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letters of Greeting 3 AHS Boards and Committees 8 Support Group 9 Acknowledgements 10 Program of conference 11 Program notes 22 Biographies 29 Exhibitors 46 AHS Chapters and Officers 48 Map of campus 54 3 4 5 Dear AHS Conference 2002 Attendees, We are happy to welcome you to the 35th National Conference of the American Harp Society. This is the third conference held in St. Paul, primarily because of its large number of lovely college campuses. The 75 members of the Minnesota Chapter of the American Harp Society have been preparing this conference for three years and sincerely hope we can make your visit comfortable, educational, and inspiring. St. Paul is the Capitol City of Minnesota and as such has much history behind it. The Sioux Indians lived in what is now the St. Paul area long before white people arrived. In 1819 the United States Army established Fort St. Anthony in a temporary building. Between 1820 and 1822, American soldiers under Colonel Josiah Snelling built Fort St. Anthony as a permanent fort. The fort covered a large area on the West Bank of the Mississippi River and soon attracted settlers. -

Original Compositions for the Lever Harp

“HARP OF WILD AND DREAM LIKE STRAIN” ORIGINAL COMPOSITIONS FOR THE LEVER HARP RACHEL PEACOCK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL 2019 © Rachel Peacock, 2019 !ii Abstract This thesis focuses on a collection of original pieces written for the solo lever harp, contextualized by a short history of the harp and its development. Brief biographical information on influential contemporary harpists who have promoted the instrument through performance, publishing new music, and recording. An analysis of the portfolio of two compositions Classmate Suite and Telling Giselle: Theme and Variations highlights musical influences and the synthesis of different traditions. !iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their invaluable direction and assistance in this graduate degree. Professor Michael Coghlan, who served as my advisor, Professor Mark Chambers, my secondary reader, and Sharlene Wallace who has mentored my harp playing and provided helpful feedback on my compositions. The encouragement and kind guidance of these people have made this thesis achievable. Special thanks to my parents, John and Marlene Peacock, and to Dave Johnson. !iv Table of Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgements iii List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Introduction 1 The Allure of the Harp 2 Training 2 Chapter One: A Brief History of the Harp 5 The Early History of the Harp 5 Turlough Carolan -

A South American Serenade

THE GRINNELL COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC PRESENTS: Guest Recital A South American Serenade Alfredo Rolando Ortiz, South American Harp Saturday, October 28, 2006 7:30 PM Sebring-Lewis Hall Bucksbaum Center for the Arts GRINNELL COLLEGE PASAJE NUMERO UNO Traditional, (Venezuela) LLANO Alfredo Rolando Ortiz b. 1946 FULGIDA LUNA Traditional, (Venezuela) (Bright Moon) WALTZ FOR A BIRTH Ortiz Originally improvised in the delivery room during the birth of his daughter, Michelle, December 31st, 1980 DANZA DE LUZMA Ortiz To his daughter, Luzma UNA LUZ EN EL MAR Ortiz (A Light in the Sea) Dedicated to his wife, Luz Marina SI QUEDARA SIN TI Ortiz (If I ever lost you) ARENA Y SEDA Ortiz (Sand and Silk) Dedicated to his wife, Luz Marina ZAYANTE Ortiz Intermission TU VENTANA Ortiz (Your window) TUPINAMBA Adolfo Lara (Colombia) MILONGA PARA AMAR Ortiz (Milonga for Loving) Dedicated to his wife, Luz Marina MOLIENDO CAFE José Manso, (Venezuela) (Grinding Coffee) MERENGUE ROJO Ortiz “FAVORITAS DE SERENATA” (Serenade Favorites) Titles to be announced . perhaps IGUAZU Ortiz Dedicated to the Iguazu waterfalls, in the jungle of South America All musical arrangements by Alfredo Rolando Ortiz Compositions by Alfredo Rolando Ortiz: © Alfredo Rolando Ortiz, AROY MUSIC. All Rights Reserved The unauthorized recording or video taping of the Performance is forbiden by law. Department of Music Upcoming Events World Hand Drumming Open Jam Session Tuesday, October 31, 2006 9:00 PM Staubitz Music Rehearsal BCA 103 Music Department Applied Studios Student Recial Thursday, November 2, 2006 12:00 PM Sebring-Lewis Hall Latin American Ensemble Gabriel Espinosa, Director Saturday, November 4,2006 7:30 PM Sebring-Lewis Hall D. -

Fall 2021 Folk Harp Journal Article on the Joropo Genre

Arpa By Patrice Fisher and Friends Joropo is a Latin American musical genre, which originated in Venezuela. The word itself means fiesta or party. The feel is like a waltz, in 3/4 time, but more syncopated and polyrhythmic. I don’t pretend to be an expert on Joropo, but fell in love with this genre many years ago, when I participated in a music festival in Caracas, Venezuela. The best part of the festival was the Jopportunity to listen to all the other musicians who were performing there. This experience was the inspiration for my composition, “Joropo Para Lili,” on page 43. Even though my tune is not a traditional Joropo, the arrangement was influenced by the music that I heard in Venezuela. I created a virtual class on how to play “Joropo Para Lili” and the video is on my Patrice Fisher and Arpa YouTube page. As well as a playlist of some of my favorite harpists playing in Joropo Style. I reached out to four of my Latin American harpist friends to try to gain a better understanding of the Joropo genre, so that I could share this wonderful genre with you. Hopefully, you’ll learn more about the Joropo genre from the perspectives of many harpists in this article. This beautiful music often features harpists in a leading role. You can find many examples, by searching for some Alfredo Rolando Ortiz, of the mentioned links or artists names on YouTube. Angel Tolosa, and Patrice Fisher at Listen for yourself and I hope that you can incorporate a Somerset Harp Festival in 2019. -

International Harp Competitions and Master

FALL 2019 • VOLUME XIII, NO. 5 World Harp congress eviewTHE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLD HARP CONGRESS, INC. NOW EVEN EASIER TRY OUR ENHANCED STRING SELECTOR, YOU CAN SEARCH BY BRAND OR BY HARP MODEL. www.harp.com The best site for ordering strings, music and harp accessories. Discover passion à la française Discover Camac Camac Centre Paris Workshop & Offices 92, rue Petit La Richerais BP15 75019 Paris, France 44850 Mouzeil, France www.camac-harps.com WORLD HARP CONGRESS, INC. Founder: Phia Berghout, The Netherlands The World Harp Congress was established in 1981 and incorporated in 1982. It originated from the Harpweeks in The Netherlands, organized by Phia Berghout and Maria Korchinska, that first met in 1960. The WHC is held every three years around the world and seeks to promote the exchange of ideas, stimulate contact, and encourage the composition of new music for the harp. Phia Berghout 1983 Maastricht, The Netherlands 2002 Geneva, Switzerland 1985 Jerusalem, Israel 2005 Dublin, Ireland 1987 Vienna, Austria 2008 Amsterdam, The Netherlands 1990 Paris/Sèvres, France 2011 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 1993 Copenhagen, Denmark 2014 Sydney, Australia 1996 Tacoma/Seattle, Washington, USA 2017 Hong Kong, China 1999 Prague, The Czech Republic 2020 Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom WORLD HARP CONGRESS, INC. MEMBERS OF THE CORPORATION Founder: Phia Berghout, The Netherlands Daphne Boden, United Kingdom Founding Chair: Ann Stockton, USA Alexandre Bonnet, The Netherlands Founding Artistic Director: Susann McDonald, USA Clíona Doris, Ireland Founding WHC Review Editor: Linda Wood Rollo, USA Mario Falcao, Portugal/USA Chair Emerita: Patricia Wooster, USA Mercedes Gómez, Mexico Kumiko Inoue, Japan Founding Committee Mieko Inoue, Japan Phia Berghout, The Netherlands Kathy Kienzle, USA Mario Falcao, Portugal/USA Sheila Larchet Cuthbert, Ireland Kumiko Inoue, Japan Susann McDonald, USA Marcela Kozikova, Czechoslovakia Isabelle Perrin, Norway/France Susann McDonald, USA Lieve Robbroeckx, Belgium Sylvia Meyer, USA Natalia Shameyeva, Russia Robert A.