World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

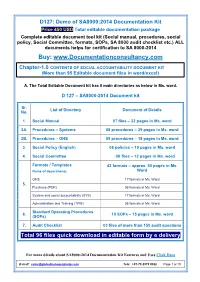

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Suggestions from Social Accountability International

Suggestions from Social Accountability International (SAI) on the work agenda of the UN Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises Social Accountability International (SAI) is a non-governmental, international, multi-stakeholder organization dedicated to improving workplaces and communities by developing and implementing socially responsible standards. SAI recognizes the value of the UN Working Group’s mandate to promote respect for human rights by business of all sizes, as the implementation of core labour standards in company supply chains is central to SAI’s own work. SAI notes that the UN Working Group emphasizes in its invitation for proposals from relevant actors and stakeholders, the importance it places not only on promoting the Guiding Principles but also and especially on their effective implementation….resulting in improved outcomes . SAI would support this as key and, therefore, has teamed up with the Netherlands-based ICCO (Interchurch Organization for Development) to produce a Handbook on How To Respect Human Rights in the International Supply Chain to assist leading companies in the practical implementation of the Ruggie recommendations. SAI will also be offering classes and training to support use of the Handbook. SAI will target the Handbook not just at companies based in Western economies but also at those in emerging countries such as Brazil and India that have a growing influence on the world’s economy and whose burgeoning base of small and medium companies are moving forward in both readiness, capacity and interest in managing their impact on human rights. SAI has long term relationships working with businesses in India and Brazil, where national companies have earned SA8000 certification and where training has been provided on implementing human rights at work to numerous businesses of all sizes. -

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure Under Threat of Audit∗

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit∗ Thomas P. Lyon†and John W. Maxwell‡ May 23, 2007 Abstract We present an economic model of greenwash, in which a firm strategi- cally discloses environmental information and a non-governmental organi- zation (NGO) may audit and penalize the firm for failing to fully disclose its environmental impacts. We show that disclosures increase when the likelihood of good environmental performance is lower. Firms with in- termediate levels of environmental performance are more likely to engage in greenwash. Under certain conditions, NGO punishment of greenwash induces the firm to become less rather than more forthcoming about its environmental performance. We also show that complementarities with NGO auditing may justify public policies encouraging firms to adopt en- vironmental management systems. 1Introduction The most notable environmental trend in recent years has been the shift away from traditional regulation and towards voluntary programs by government and industry. Thousands of firms participate in the Environmental Protec- tion Agency’s partnership programs, and many others participate in industry- led environmental programs such as those of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Chicago Climate Exchange, and the American Chemistry Council’s “Responsible Care” program.1 However, there is growing scholarly concern that these programs fail to deliver meaningful environmental ∗We would like to thank Mike Baye, Rick Harbaugh, Charlie Kolstad, John Morgan, Michael Rauh, and participants in seminars at the American Economic Association meetings, Canadian Resource and Environmental Economics meetings, Dartmouth, Indiana University, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and University of Florida for their helpful comments. -

Campaigners' Guide to Financial Markets

The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets THETHE CAMPCAMPAIGNERS’AIGNERS’ GUIDEGUIDE TTOO FINFINANCIALANCIAL MARKETSMARKETS Effff ective Lobbying of Companies and Financial Institutions Nicholas Hildyard Mark Mansley 1 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets 2 The Campaigners’ Guide to Financial Markets Contents Preface – 7 Acknowledgements – 9 1. FINANCIAL MARKETS - A NEW POLITICAL SPACE – 11 A world transformed – 12 The impacts of globalisation – 14 The growing power of the private sector – 16 The shifting space for change – 17 Lobbying the markets – 18 The power of the market – Markets as “neutral ground” – NGO strengths: market weaknesses – Increasing consumer awareness – Globalisation and increased corporate vulnerability – The rise of ethical shareholding – Changing institutional cultures – New regulatory measures – A willingness to change? The limits of market activism – 33 Is a financial campaign appropriate? – 33 Boxes The increasing economic power of the private sector – 13 What are financial markets? – 14 Changing the framework: From Seattle to Prague – 18 Project finance – 20 Consumer and shareholder activism – 23 A bank besieged: Consumer power against bigotry – 25 Huntingdon Life Sciences: Naming and shaming – 27 First do no harm – 30 The impact of shareholder activism – the US experience (by Michelle Chan-Fishel) – 33 Put your own house in order – 34 Internal review – 33 2. UNDERSTANDING THE MARKETS – PSYCHOLOGY,,, ARGUMENTS AND OPENINGS – 37 Using the mentality of the market to your advantage – 38 Exposing the risks – 39 Key pressure points and how to use them – 41 Management quality – Business strategy – Financial risk: company analysis / project analysis – Non–financial risks – Political risks – Legal risks – Environmental risks – Reputational risks Matching the pressure points to the financial player – 54 Boxes Reading the balance sheet – 40 ABB – Moving out of dams – 43 Three Gorges: Bond issues challenged – 47 3. -

Review of SA8000 2008

SA8000:2008 Review of SA8000 2008 © Social Accountability Accreditation Services June 2010 © SAAS 2010 Social Accountability International • Convenes key stakeholders to develop consensus-based voluntary global social standards. • Created the SA8000 Standard. • Delivers training & technical assistance. • Contracts with SAAS to license qualified organizations to verify compliance with SA8000. www.sa-intl.org © SAAS 2010 Social Accountability Accreditation Services • Formerly Accreditation Department of SAI (since 1997). • Incorporated as own organization in 2007 • Primary activities: To accredit and monitor organizations seeking to act as certifiers of compliance with SA8000; To provide confidence to all stakeholders in SAAS accreditation decisions and in the certification decisions of its accredited CBs; To continually improve the SAAS accreditation function activities and systems, in compliance with ISO/IEC Guide 17011 and SAAS Procedures. www.saasaccreditation.org © SAAS 2010 Perspective: Impact of Economic Globalization • Greater expansion of markets • Greater mobility of capital • Shifts in balance of trade • Changes in balance of purchase power (currencies) • Job shifts from developed to developing countries • Competition between countries to be low-cost producers and attract investors • Corporations growing in power and influence (Walmart 288 billion in revenues (2005) vs. Switzerland 251 billion GDP or Ireland 156 billion GDP) © SAAS 2010 Market Pressures: The Business Risk Factors • Increased influence and power of MNCs in -

Sustainability Report Edition: 2017

Develop. Supply. Manage. Full-service supplier of professional clothing. SUSTAINABILITY REPORT Edition: 2017 www.workfashion.com Tabel of contents Preface workfashion.com substainability report Strengthening co-operation 03 Strengthening co-operation At workfashion.com, the 2017 business year was marked by new products, successful partner- ships, the focus on Macedonia as a production location and the 50th anniversary. There were 04 50 years of workfashion.com numerous challenges but these were outweighed by the successes, which enable us to look back with pride on the past year. 05 Our services 06 2017 at a glance 07 Our stakeholders 08-11 The world of labels 12-13 Targets and activities 2017 14-15 Living Wage project with Igmatomiteks 16 Clear rules lead to commitment 18-21 Sustainability in the company DNA 22-23 Systematic control – because sustainability is not a coincidence 26-27 Overview of our production partners 28-29 Classification of producing countries in 2017 Sustainability in focus Successful partnerships 30-33 Transparency in detail – our partners All our business decisions are based on the three A co-operative working model with all our suppli- pillars of sustainability: efficiency, social fairness ers is the basis of successful business activity. For 35 The direct line for production employees and environmental sustainability. In 2017, we once example, we maintain long-term partnerships with again strengthened our pioneering role in the area many of our production sites and suppliers, which 37 Knowledge leads to sustainability of sustainability through our involvement in various enable joint development. We are particularly committees and by giving presentations on sus- proud of the co-operation with our Swiss suppli- 38-39 Exchange Macedonia-Switzerland tainability. -

Courses in English

Courses taught in English at Albstadt-Sigmaringen University, Germany as of 20.10.2020. Bachelor level (for Master level see last page) If not mentioned otherwise, the classes will be offered during each semester. The number in the right hand column with the column title Sem. indicates the semester level (i.e. 3 = 2nd year, 1st semester; 6 = 3rd year, 1st semester). Students can mix classes from each semester level (Bachelor students only on Bachelor level, Master students on both Bachelor and Master level) and also from different campuses. Courses related to Business: a) Albstadt campus: Lecturer Title Code Credits Sem. Prof. Gerhards Quality Management I: IP 20090 2 ECTS 4 The students get an overview of the different (BT 24010) aspects of quality and quality management. The students get an overview of processes in product- an quality management of clothing companies and their influence to quality The students learn the link between quality and sewing faults. The students learn different methods to find the reasons for bad quality Prof. Gerhards Quality Management II: IP 20100 3 ECTS 6 The students learn the necessity of quality- (BT 24530) management-systems in companies The students get an overview of the ISO 9000 ff family and learn to work with it The students can develop the philosophy of Total Quality Management out of ISO 9004 Prof. Kimmerle Textile Ecology and sustainability IP 20055 4 ECTS 6 In the lecture, we examine and elaborate possible strategies for textile and clothing companies, how to setup an efficient working CSR team. We compare certification facilities and best available technologies within the complete global textile supply chain. -

Social Accountability 8000

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD SAI SA8000®: 2008 SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY 8000 SA8000® is a registered trademark of Social Accountability International Page 2 of 10 SA8000:2008 ABOUT THE STANDARD This is the third issue of SA8000, an auditable standard for a third-party verification system, setting out the voluntary requirements to be met by employers in the workplace, including workers’ rights, workplace conditions, and management systems. The normative elements of this standard are based on national law, international human rights norms and the conventions of the ILO. The SA8000 standard can be used along with the SA8000 Guidance Document to assess the compliance of a workplace with these standards. The SA8000 Guidance Document helps to explain SA8000 and how to implement its requirements; provides examples of methods for verifying compliance; and serves as a handbook for auditors and for companies seeking certification of compliance with SA8000. The Guidance Document can be obtained from SAI upon request for a small fee. SA8000 is revised periodically as conditions change, and to incorporate corrections and improvements received from interested parties. Many interested parties have contributed to this version. It is hoped that both the standard and its Guidance Document will continue to improve, with the help of a wide variety of people and organisations. SAI welcomes your suggestions as well. To comment on SA8000, the associated SA8000 Guidance Document , or the framework for certification, please send written remarks to SAI at the address indicated below. SAI Social Accountability International © SAI 2008 The SA8000 standard may be reproduced only if prior written permission from SAI is obtained. -

Jack Wolfskin Performance Check 2019

BRAND PERFORMANCE CHECK Jack Wolfskin PUBLICATION DATE: JUNE 2019 this report covers the evaluation period 01-10-2017 to 30-09-2018 ABOUT THE BRAND PERFORMANCE CHECK Fair Wear Foundation believes that improving conditions for apparel product location workers requires change at many levels. Traditional efforts to improve conditions focus primarily on the product location. FWF, however, believes that the management decisions of clothing brands have an enormous influence for good or ill on product location conditions. FWF’s Brand Performance Check is a tool to evaluate and report on the activities of FWF’s member companies. The Checks examine how member company management systems support FWF’s Code of Labour Practices. They evaluate the parts of member company supply chains where clothing is assembled. This is the most labour intensive part of garment supply chains, and where brands can have the most influence over working conditions. In most apparel supply chains, clothing brands do not own product locations, and most product locations work for many different brands. This means that in most cases FWF member companies have influence, but not direct control, over working conditions. As a result, the Brand Performance Checks focus primarily on verifying the efforts of member companies. Outcomes at the product location level are assessed via audits and complaint reports, however the complexity of the supply chains means that even the best efforts of FWF member companies cannot guarantee results. Even if outcomes at the product location level cannot be guaranteed, the importance of good management practices by member companies cannot be understated. Even one concerned customer at a product location can have significant positive impacts on a range of issues like health and safety conditions or freedom of association. -

Guidance Document for Social Accountability 8000 (Sa8000®:2014)

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT FOR SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY 8000 (SA8000®:2014) RELEASE DATE: MAY 2016 SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY INTERNATIONAL 15 WEST 44TH STREET, 6TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 WEBSITE: WWW.SA-INTL.ORG EMAIL: [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE SA8000:2014 GUIDANCE DOCUMENT .............................................................................. 3 HOW TO READ THIS DOCUMENT ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1. CHILD LABOUR ................................................................................................................................................... 5 RELEVANT SA8000 DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 5 SA8000 REQUIREMENTS................................................................................................................................................. 5 BACKGROUND AND INTENT .............................................................................................................................................. 5 IMPLEMENTATION GUIDANCE ........................................................................................................................................... 8 AUDITOR GUIDANCE .................................................................................................................................................... -

Pro QC Audit Sample for ISO 9001

SA8000 Audit Report * Example Report * North America +1-813-252-4770 Latin America +52-1-333-2010712 Europe & Middle-East +49-8122-552 9590 Asia & Asia Pacific +886-2-2832-2990 Email [email protected] www.proqc.com SA8000 Social Responsibility Audit Rev. GUIDELINES 1 PURPOSE: This audit is based on defined criterion for social accountability. Scoring is based on the supplier's ability to meet the requirements. The audit focuses on factors that would result in non compliance to the social accountability standard. The intent of the audit based on the requirements of SA8000 and national/local laws is to provide useful assessment information for making sourcing decisions and reducing associated risks. SCORING: Scores are assigned based on what is done for the Pro QC client regardless of what is done for other clients. For example, if control plans are developed for other clients but not for the Pro QC client, the score must be NC. Scoring must be explained to the supplier at the opening meeting. Complies with the Requirements = C Improvement Needed = I Non-Conformance Found = NC N/A = Does Not Apply GUIDELINE FOR SCORING CONFORMANCE: Each question is assessed for conformance to the requirements of SA8000, and the auditors knowledge of the product and/or process This must be clear to the supplier at the opening meeting. Complies with Requirements = - Has objective evidence to support the question, and - Has a written procedure (when required). Improvement Needed = - Has objective evidence, but procedure needs improvement. - Has objective evidence, but no written procedure. - Has written procedure, but is lacking some objective evidence to support the question. -

Environmental Protection in the Information Age

ARTICLES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION IN THE INFORMATION AGE DANIEL C. ESTy* Information gaps and uncertaintieslie at the heart of many persistentpollution and natural resource management problems. This article develops a taxonomy of these gaps and argues that the emerging technologies of the Information Age will create new gap-filling options and thus expand the range of environmental protection strategies. Remote sensing technologies, modern telecommunications systems, the Internet, and computers all promise to make it much easier to identify harms, track pollution flows and resource consumption, and measure the resulting impacts. These developments will make possible a new structure of institutionalresponses to environmental problems including a more robust market in environmental prop- erty rights, expanded use of economic incentives and market-based regulatorystrat- egies, improved command-and-control regulation, and redefined social norms of environmental stewardship. Likewise, the degree to which policies are designed to promote information generation will determine whether and how quickly new insti- tutional approaches emerge. While some potential downsides to Information Age environmental protection remain, the promise of a more refined, individually tai- lored, and precise approach to pollution control and natural resourcemanagement looks to be significant. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 117 I. DEFINING THE ROLE OF INFORMATION IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL REALM ............................... 121 A. Information