Social Accountability International and the SA8000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Closer Look at Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Reporting: a Worldwide Sector Analysis

A CLOSER LOOK AT GLOBAL REPORTING INITIATIVE SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING: A WORLDWIDE SECTOR ANALYSIS Abstract This study analyses the worldwide diffusion of the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) Sustainability Report in all economic sectors from 1999-2011. The logistic curve model (s-shaped curve) is used to assess the current situation on both a global scale and a local scale. Additionally, instability and concentration indices are used to analyse whether the diffusion process developed in a homogeneous manner across economic sectors. Close attention has been paid to the two leading sectors worldwide, although for different reasons: the financial and energy sectors. Findings suggest that energy sector has adopted GRI reporting in an effort to be more sustainable as being more visible, polluting and international. On the other hand, the financial sector could regain market credibility and attract new investors, and GRI reporting could help it to construct a new identity defined by legitimate behaviours and an improved image The paper concludes with some reflections on the usefulness of these reports and trends. Key Words: Global Reporting Initiative; GRI; sustainability reporting; sustainability reporting diffusion; stakeholders; sustainable development; environmental policy. A CLOSER LOOK AT GLOBAL REPORTING INITIATIVE SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING: A WORLDWIDE SECTOR ANALYSIS 1. INTRODUCTION Currently, information beyond what is available in financial statements is crucial for companies to maintain a trusting relationship with their stakeholders (Krajnc and Glavic, 2005; Gilbert and Rache, 2007; Alonso-Almeida, 2009). In the past two decades, environmental and social concerns have continuously been increasing (Melé et al., 2006; Skouloudis et al., 2009). Even governments have started applying greater pressure on companies to be more compliant with regulations or recommendations (Delmas and Toffel, 2008; Prado-Lorenzo et al., 2009; Delmas and Montes- Sancho, 2010). -

On a Shared Mission UL Sustainability Report 2019 on a Shared Mission UL Sustainability Report 2019

On a shared mission UL Sustainability Report 2019 On a shared mission UL Sustainability Report 2019 In 2019, UL celebrated 125 years of working for a safer, more secure and sustainable world. As our work continues, we recognize that our mission to progress the safety, security and sustainability of our world is a call to all who hope to protect our planet, its people and the prosperity of future generations. In our first sustainability report, we share our story with the belief that by revealing our successes and challenges we will add insights to the collective journey toward a thriving, abundant future for all. 3 UL’s sustainability purpose goes beyond addressing Our services and offerings. We help our customers CEO message the effects of climate change. As an independent implement their visions of a sustainable world, as safety science company with a 125-year legacy of well, by supporting transparency in supply chains and UL has been working for a safer world proven results we must do more and demand more sourcing, enabling environmental health and safety, since 1894. That was our founding mission of ourselves than that. We must help pave the way and promoting a circular economy that replenishes 125 years ago, and that mission still excites forward to a self-sustaining world. and reuses the natural resources we rely on. Safety and engages all of us. I don’t believe continues to be our priority through our work to there could be a higher purpose than Safety, security and sustainability are interconnected. support the responsible development of resilient, endeavoring to make the world a safer, They pose similar risks and opportunities. -

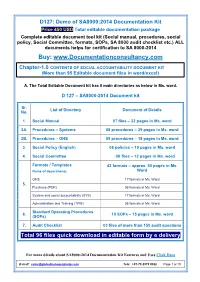

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: a Comparative Analysis Katharine V

Hastings Business Law Journal Volume 7 Article 4 Number 2 Summer 2011 Summer 1-1-2011 Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis Katharine V. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_business_law_journal Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Katharine V. Jackson, Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis, 7 Hastings Bus. L.J. 309 (2011). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal/vol7/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Business Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS A STAKEHOLDER- SHAREHOLDER THEORY OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Katharine V. Jackson* Most of the groups and individuals affected by the behavior of American public corporations do not have a voice in their governance. Just as governments retreat from regulating these entities, whether by political choice or as a result of globalization and regulatory arbitrage,1 stakeholders' 2 ability to shape corporate behavior themselves remains weak. Government empowers only one corporate stakeholder group- employees-to bargain with corporations for terms in their own interest. 1. See Eugene D. Genovese, Secularism in the General Crisis of Capitalism, 42 AM. J. JURIS. 195, 202 (1997) (multinational corporations are coming to control the "world economy, over which.,.. centralized national governments have less and less control."); Larry CatA Backer, Multinational Corporations, TransnationalLaw: The United Nations ' Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations as a Harbinger of Corporate Social Responsibility in International Law, 37 CoLUM. -

Suggestions from Social Accountability International

Suggestions from Social Accountability International (SAI) on the work agenda of the UN Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises Social Accountability International (SAI) is a non-governmental, international, multi-stakeholder organization dedicated to improving workplaces and communities by developing and implementing socially responsible standards. SAI recognizes the value of the UN Working Group’s mandate to promote respect for human rights by business of all sizes, as the implementation of core labour standards in company supply chains is central to SAI’s own work. SAI notes that the UN Working Group emphasizes in its invitation for proposals from relevant actors and stakeholders, the importance it places not only on promoting the Guiding Principles but also and especially on their effective implementation….resulting in improved outcomes . SAI would support this as key and, therefore, has teamed up with the Netherlands-based ICCO (Interchurch Organization for Development) to produce a Handbook on How To Respect Human Rights in the International Supply Chain to assist leading companies in the practical implementation of the Ruggie recommendations. SAI will also be offering classes and training to support use of the Handbook. SAI will target the Handbook not just at companies based in Western economies but also at those in emerging countries such as Brazil and India that have a growing influence on the world’s economy and whose burgeoning base of small and medium companies are moving forward in both readiness, capacity and interest in managing their impact on human rights. SAI has long term relationships working with businesses in India and Brazil, where national companies have earned SA8000 certification and where training has been provided on implementing human rights at work to numerous businesses of all sizes. -

Corporate Social Responsibility

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Corporate Social Responsibility Contact person- Corporate Social Responsibility / Ansprechpartner Corporate Social Responsibility Eissmann has established a Compliance Committee responsible for implementing and enforcing the Code of Conduct. The Compliance Committee comprises the Managing Directors of Eissmann Group Automotive and the Head of the Human Resources Division. Where violations take place within the subsidiaries, the relevant Managing Director in the Compliance Committee is involved. If members of the Compliance Committee are affected, they cannot work on their own account within the Compliance Committee. In the subsidiaries, it is the Head of Human Resources who acts as contact in matters of compliance and who is entrusted with the implementation of the Code of Conduct. Every employee is entitled to approach the Head of Human Resources of his or her company, the responsible Human Resources management, or the members of the Compliance Committee on matters concerning compliance. The contact can also be made anonymously. The relevant contact details and further information on the subject of compliance can be found in the IMS. Employees who report violations of the Code of Conduct or suspected violations to Eissmann will not be penalized for so doing. Addition: Members of the Compliance Committee: CEO, CFO, BL-PM, BL-GSM, Group Financial Auditor Source: Code of Conduct 4 Working conditions / Arbeitsbedingungen Eissmann gives its employees fair pay and fair working conditions in compliance with all statutory requirements. We reject all forms of forced labor and child labor. Source: Code of Conduct 3.1 Chapter 3 Bribery / Bestechung Gifts, payments, services: Eissmann observes the rules of fair competition and the free market. -

From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability

Hastings Business Law Journal Volume 16 Number 1 Winter 2020 Article 3 Winter 2020 From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability Min Yan Daoning Zhang Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Min Yan and Daoning Zhang, From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability, 16 Hastings Bus. L.J. 43 (2020). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal/vol16/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Business Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 - YAN _ZHANG - V9 - KC - 10.27.19.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2019 11:11 AM From Corporate Responsibility to Corporate Accountability Min Yan* and Daoning Zhang** I. INTRODUCTION The concept of corporate responsibility or corporate social responsibility (“CSR”) keeps evolving since it appeared. The emphasis was first placed on business people’s social conscience rather than on the company itself, which was well reflected by Howard Bowen’s landmark book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman.1 Then CSR was defined as responsibilities to society, which extends beyond economic and legal obligations by corporations.2 Since then, corporate responsibility is thought to begin where the law ends. 3 In other words, the concept of social responsibility largely excludes legal obedience from the concept of social responsibility. An analysis of 37 of the most used definitions of CSR also shows “voluntary” as one of the most common dimensions.4 Put differently, corporate responsibility reflects the belief that corporations have duties beyond generating profits for their shareholders. -

Internal Audit Report Stakeholder Management October 2020

Internal Audit Report Stakeholder Management October 2020 Contents 01 Introduction 02 Background 03 Key Findings 04 Areas for Further Improvement and Action Plan Appendices A1 Audit Information In the event of any questions arising from this report please contact Peter Cudlip, Partner ([email protected]) or Darren Jones, Manager ([email protected]). Disclaimer This report (“Report”) was prepared by Mazars LLP at the request of the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) and terms for the preparation and scope of the Report have been agreed with them. The matters raised in this Report are only those which came to our attention during our work. Whilst every care has been taken to ensure that the information provided in this Report is as accurate as possible, We have only been able to base findings on the information and documentation provided and consequently no complete guarantee can be given that this Report is necessarily a comprehensive statement of all the weaknesses that exist, or of all the improvements that may be required. The Report was prepared solely for the use and benefit of the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) and to the fullest extent permitted by law Mazars LLP accepts no responsibility and disclaims all liability to any third party who purports to use or rely for any reason whatsoever on the Report, its contents, conclusions, any extract, reinterpretation, amendment and/or modification. Accordingly, any reliance placed on the Report, its contents, conclusions, any extract, reinterpretation, amendment and/or modification by any third party is entirely at their own risk. Please refer to the Statement of Responsibility in Appendix A1 of this report for further information about responsibilities, limitations and confidentiality. -

CSR in LEO Pharma - Focus Areas 2013-2016

– Corporate Social Responsibility Report — we help people achieve healthy skin Environment & Safety People & Health Compliance & Ethics Partnerships & Collaboration Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) LEO Pharma CSR Report 2014 – Corporate Social Responsibility Report LEO Pharma in brief Founded in 1908 Headquarters in Denmark Offering care solutions to patients in more than 4,800 employees 100 Present in countries 61 countries with Owned by the LEO employees LEO Foundation Therapeutic areas Psoriasis Actinic keratosis Skin infections Eczema Acne Thrombosis Other areas of care Page – 2 Contents 5 Statement from the President & CEO 6 The commitment of LEO Pharma 7 LEO CSR Strategy 8 LEO Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Policy 9 CSR in LEO Pharma - Focus areas 2013-2016 10 Environment & Safety 14 People & Health 18 Compliance & Ethics 22 Partnerships & Collaboration 26 Appendix: Focus areas, goals and milestones 2013-2016 30 Glossary 31 LEO values 31 Contact This report represents LEO Pharma’s compliance with Section 99a and 99b of the Danish Financial Statements Act Page – 3 – Corporate Social Responsibility Report LEO mission We help people achieve healthy skin LEO vision We are the preferred dermatology care partner improving people’s lives around the world Page – 4 Statement from the President & CEO Dear stakeholders, Our mission in LEO Pharma is to help people achieve healthy skin and in 2014 we have helped 48 million patients. LEO Pharma is committed to changing the impact skin diseases have on people’s lives. In 2014, the WHO resolution on psoriasis was adopted, recognising psoriasis as a chronic and disabling disease – a significant step for patients worldwide – which LEO Pharma We help people achieve supports. -

Eugenics and Domestic Science in the 1924 Sociological Survey of White Women in North Queensland

This file is part of the following reference: Colclough, Gillian (2008) The measure of the woman : eugenics and domestic science in the 1924 sociological survey of white women in North Queensland. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/5266 THE MEASURE OF THE WOMAN: EUGENICS AND DOMESTIC SCIENCE IN THE 1924 SOCIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WHITE WOMEN IN NORTH QUEENSLAND Thesis submitted by Gillian Beth COLCLOUGH, BA (Hons) WA on February 11 2008 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Arts and Social Sciences James Cook University Abstract This thesis considers experiences of white women in Queensland‟s north in the early years of „white‟ Australia, in this case from Federation until the late 1920s. Because of government and health authority interest in determining issues that might influence the health and well-being of white northern women, and hence their families and a future white labour force, in 1924 the Institute of Tropical Medicine conducted a comprehensive Sociological Survey of White Women in selected northern towns. Designed to address and resolve concerns of government and medical authorities with anxieties about sanitation, hygiene and eugenic wellbeing, the Survey used domestic science criteria to measure the health knowledge of its subjects: in so doing, it gathered detailed information about their lives. Guided by the Survey assessment categories, together with local and overseas literature on racial ideas, the thesis examines salient social and scientific concerns about white women in Queensland‟s tropical north and in white-dominated societies elsewhere and considers them against the oral reminiscences of women who recalled their lives in the North for the North Queensland Oral History Project. -

Deloitte.Co.Za Conducted

Stakeholder Engagement 1 Next Introduction Important stakeholder groups are inherently known to An Integrated Report is a single report that the companies and most companies are interacting with International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) these stakeholder groups in some form or another as a anticipates will become an organisation’s primary report. matter of course. Such engagement happens in different This primary report needs to tell the overall story of the formats and at various levels in any organisation, and company by providing material and relevant information the process has been embedded in sound business specifically aimed at the general needs of wide range of practices for some time. However, this process is often key stakeholders, within the context of an ever-evolving ad-hoc at many companies without a formal structure business, social and physical environment. and process in place. Business leaders and managers will normally be able to list their key stakeholders and One of the fundamentals of the Integrated Reporting concerns, but not furnish the structure and process of process is stakeholder engagement. It is the key starting engagement as easily. point for a company, not only in terms of its corporate reporting cycle, but also connects to its business strategy The value of the stakeholder engagement process can and demonstrates how a company is responsive to the be greatly enhanced while the risk of missing important legitimate needs and concerns of key stakeholders. But perspectives – which may negatively affect reputation let’s start with the definition: what are stakeholders and and cause embarrassment or worse – be reduced by what is stakeholder engagement? formalising the implementation of a formal stakeholder engagement policy. -

Survey of Stakeholder Perspectives of Audit Quality – Detailed Discussion of Survey Results

IFAC Board Survey on Audit Quality Prepared by the Staff of the IAASB December 2012 Survey of Stakeholder Perspectives of Audit Quality – Detailed Discussion of Survey Results This document was prepared by the Staff of the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). This IAASB develops auditing and assurance standards and guidance for use by all professional accountants under a shared standard-setting process involving the Public Interest Oversight Board, which oversees the activities of the IAASB, and the IAASB Consultative Advisory Group, which provides public interest input into the development of the standards and guidance. The objective of the IAASB is to serve the public interest by setting high-quality auditing, assurance, and other related standards and by facilitating the convergence of international and national auditing and assurance standards, thereby enhancing the quality and consistency of practice throughout the world and strengthening public confidence in the global auditing and assurance profession. The structures and processes that support the operations of the IAASB are facilitated by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). Copyright © December 2012, February 2014 by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). For copyright, trademark, and permissions information, please see page12. A Framework for Audit Quality Survey of Stakeholder Perspectives of Audit Quality – Detailed Discussion of Survey Results 1. Some academics have observed that audit involves both a technical component and a service component. The relative importance of these two components is likely to vary between different stakeholder groups. 2. The technical component of audit quality is often considered as having been achieved when there is a high probability that an auditor will both (a) discover a misstatement in the client’s financial statements, and (b) report that misstatement.