Wilderness Study Report Us Department of the Interior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Density, Distribution and Habitat Requirements for the Ozark Pocket Gopher (Geomys Bursarius Ozarkensis)

DENSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT REQUIREMENTS FOR THE OZARK POCKET GOPHER (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis) Audrey Allbach Kershen, B. S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Kenneth L. Dickson, Co-Major Professor Douglas A. Elrod, Co-Major Professor Thomas L. Beitinger, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kershen, Audrey Allbach, Density, distribution and habitat requirements for the Ozark pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis). Master of Science (Environmental Science), May 2004, 67 pp., 6 tables, 6 figures, 69 references. A new subspecies of the plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis), located in the Ozark Mountains of north central Arkansas, was recently described by Elrod et al. (2000). Current range for G. b. ozarkensis was established, habitat preference was assessed by analyzing soil samples, vegetation and distance to stream and potential pocket gopher habitat within the current range was identified. A census technique was used to estimate a total density of 3, 564 pocket gophers. Through automobile and aerial survey 51 known fields of inhabitance were located extending the range slightly. Soil analyses indicated loamy sand as the most common texture with a slightly acidic pH and a broad range of values for other measured soil parameters and 21 families of vegetation were identified. All inhabited fields were located within an average of 107.2m from waterways and over 1,600 hectares of possible suitable habitat was identified. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Appreciation is extended to the members of my committee, Dr. Kenneth Dickson, Dr. Douglas Elrod and Dr. -

(Poaceae: Paniceae), with Lectotypification of Panicum Divisum

Phytotaxa 181 (1): 059–060 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.181.1.5 A new combination in Cenchrus (Poaceae: Paniceae), with lectotypification of Panicum divisum FILIP VERLOOVE1, RAFAËL GOVAERTS2 & KARL PETER BUTTLER3 1Botanic Garden of Meise, Nieuwelaan 38, B-1860 Meise, Belgium [[email protected]] 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, England [[email protected]] 3Orber Straße 38, D-60386 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [[email protected]] Abstract The new combination, Cenchrus divisus (J.F. Gmelin) Verloove, Govaerts & Buttler, is proposed for the species widely known as Pennisetum divisum (J.F. Gmelin) Henrard, and a lectotype for Panicum divisum J.F. Gmelin is designated. Key words: Cenchrus, lectotypification, nomenclature, Panicum As a result of recent molecular phylogenetic studies the generic boundaries of Cenchrus L. and related genera have considerably changed. Donadio et al. (2009) found that Cenchrus and Pennisetum Rich. are very closely related and demonstrated that most species of Cenchrus are in fact nested in Pennisetum. Chemisquy et al. (2010) confirmed these results and recommended merging both genera. The generic name Cenchrus having priority, all species of Pennisetum needed to be transferred to Cenchrus. Morrone (in Chemisquy et al., 2010) published new combinations in Cenchrus for most of the species and Symon (2010) made some additional name changes for a few Australian taxa. The correct names in Cenchrus for all but one of the 15 Pennisetum species in Europe and the Mediterranean area, including four new combinations, were given in Verloove (2012). -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Aquiloeurycea Scandens (Walker, 1955). the Tamaulipan False Brook Salamander Is Endemic to Mexico

Aquiloeurycea scandens (Walker, 1955). The Tamaulipan False Brook Salamander is endemic to Mexico. Originally described from caves in the Reserva de la Biósfera El Cielo in southwestern Tamaulipas, this species later was reported from a locality in San Luis Potosí (Johnson et al., 1978) and another in Coahuila (Lemos-Espinal and Smith, 2007). Frost (2015) noted, however, that specimens from areas remote from the type locality might be unnamed species. This individual was found in an ecotone of cloud forest and pine-oak forest near Ejido La Gloria, in the municipality of Gómez Farías. Wilson et al. (2013b) determined its EVS as 17, placing it in the middle portion of the high vulnerability category. Its conservation status has been assessed as Vulnerable by IUCN, and as a species of special protection by SEMARNAT. ' © Elí García-Padilla 42 www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com The herpetofauna of Tamaulipas, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status SERGIO A. TERÁN-JUÁREZ1, ELÍ GARCÍA-PADILLA2, VICENTE Mata-SILva3, JERRY D. JOHNSON3, AND LARRY DavID WILSON4 1División de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación, Instituto Tecnológico de Ciudad Victoria, Boulevard Emilio Portes Gil No. 1301 Pte. Apartado postal 175, 87010, Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Email: [email protected] 2Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca, Código Postal 68023, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968-0500, United States. E-mails: [email protected] and [email protected] 4Centro Zamorano de Biodiversidad, Escuela Agrícola Panamericana Zamorano, Departamento de Francisco Morazán, Honduras. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The herpetofauna of Tamaulipas, the northeasternmost state in Mexico, is comprised of 184 species, including 31 anurans, 13 salamanders, one crocodylian, 124 squamates, and 15 turtles. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Characterization of Arm Autotomy in the Octopus, Abdopus Aculeatus (D’Orbigny, 1834)

Characterization of Arm Autotomy in the Octopus, Abdopus aculeatus (d’Orbigny, 1834) By Jean Sagman Alupay A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair Professor David Lindberg Professor Damian Elias Fall 2013 ABSTRACT Characterization of Arm Autotomy in the Octopus, Abdopus aculeatus (d’Orbigny, 1834) By Jean Sagman Alupay Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair Autotomy is the shedding of a body part as a means of secondary defense against a predator that has already made contact with the organism. This defense mechanism has been widely studied in a few model taxa, specifically lizards, a few groups of arthropods, and some echinoderms. All of these model organisms have a hard endo- or exo-skeleton surrounding the autotomized body part. There are several animals that are capable of autotomizing a limb but do not exhibit the same biological trends that these model organisms have in common. As a result, the mechanisms that underlie autotomy in the hard-bodied animals may not apply for soft bodied organisms. A behavioral ecology approach was used to study arm autotomy in the octopus, Abdopus aculeatus. Investigations concentrated on understanding the mechanistic underpinnings and adaptive value of autotomy in this soft-bodied animal. A. aculeatus was observed in the field on Mactan Island, Philippines in the dry and wet seasons, and compared with populations previously studied in Indonesia. -

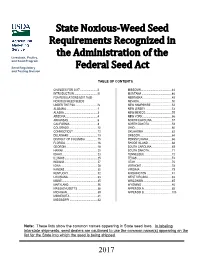

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Federal Seed Act

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Livestock, Poultry, and Seed Program Seed Regulatory Federal Seed Act and Testing Division TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGES FOR 2017 ........................ II MISSOURI ........................................... 44 INTRODUCTION ................................. III MONTANA .......................................... 46 FSA REGULATIONS §201.16(B) NEBRASKA ......................................... 48 NOXIOUS-WEED SEEDS NEVADA .............................................. 50 UNDER THE FSA ............................... IV NEW HAMPSHIRE ............................. 52 ALABAMA ............................................ 1 NEW JERSEY ..................................... 53 ALASKA ............................................... 3 NEW MEXICO ..................................... 55 ARIZONA ............................................. 4 NEW YORK ......................................... 56 ARKANSAS ......................................... 6 NORTH CAROLINA ............................ 57 CALIFORNIA ....................................... 8 NORTH DAKOTA ............................... 59 COLORADO ........................................ 10 OHIO .................................................... 60 CONNECTICUT .................................. 12 OKLAHOMA ........................................ 62 DELAWARE ........................................ 13 OREGON............................................. 64 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ................. 15 PENNSYLVANIA................................ -

ECOSYSTEM DEGRADATION, HABITAT LOSS and SPECIES DECLINE in ARID and SEMI-ARID AUSTRALIA DUE to the INVASION of BUFFEL GRASS (Cenchrus Ciliaris and C

THREAT ABATEMENT ADVICE FOR ECOSYSTEM DEGRADATION, HABITAT LOSS AND SPECIES DECLINE IN ARID AND SEMI-ARID AUSTRALIA DUE TO THE INVASION OF BUFFEL GRASS (Cenchrus ciliaris AND C. pennisetiformis) This threat abatement advice reflects the best available information at the time of development (October 2014) Last updated April 2015 To provide information updates please email [email protected] Purpose The purpose of this threat abatement advice is to identify key actions and research to abate the threat of ecosystem degradation, habitat loss and species decline in arid and semi-arid Australia due to the invasion of buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris and C. pennisetiformis1). Buffel grass comprises a suite of species and ecotypes native to Africa, Western and Southern Asia that are now rapidly colonising arid ecosystems in Australia. Abatement of this threat can help ensure the conservation of biodiversity assets including threatened species and ecological communities listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), Ramsar sites and properties on the World Heritage List. Other significant assets such as Indigenous cultural sites, state and territory listed assets and remnant vegetation would also be better protected. This advice provides information and guidance for stakeholders at national, state, regional and local levels. It suggests on-ground activities that can be implemented by local communities, natural resource management groups or interested individuals such as landholders. It also suggests actions that can be undertaken by government agencies, local councils, research organisations, industry bodies or non-government organisations. The intention of this advice is to highlight those actions considered through consultation to be of highest priority and which may be feasible, rather than to comprehensively list all actions which may abate the threat and impacts posed by buffel grass. -

Habitat Characteristics That Influence Maritime Pocket Gopher Densities

The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 26:14-24 (2013) 14 © Agricultural Consortium of Texas Habitat Characteristics That Influence Maritime Pocket Gopher Densities Jorge D. Cortez1 Scott E. Henke*,1 Richard Riddle2 1Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, MSC 218, Texas A&M University- Kingsville, Kingsville, TX 78363 2United States Navy, 8851 Ocean Drive, Corpus Christi, TX 78419-5226 ABSTRACT The Maritime pocket gopher (Geomys personatus maritimus) is a subspecies of Texas pocket gopher endemic to the Flour Bluff area of coastal southern Texas. Little is known about the habitat and nutritional requirements of this subspecies. The amount and quality of habitat necessary to sustain Maritime pocket gophers has not been studied. Our objectives were to assess the habitat, vegetation, and nutritional parameters available to Maritime pocket gophers at four different levels of gopher mound density. We chose study sites with zero, low (25-50 mounds/ha), intermediate (75-150 mounds/ha), and high (>200 mounds/ha) gopher mound densities. Vegetation and soil samples were collected using 0.25 m2 quadrats; vegetation was divided into above- and below-ground biomass for analysis. Maritime pocket gophers avoided areas of clay soils with high levels of calcium, magnesium, sulfur, and sodium compounds. A direct relationship existed between gopher activity within an area and vegetation biomass. However, nutritional quality of an area did not appear to be a determining factor for the presence of Maritime pocket gophers. KEY WORDS: Population density, Geomys personatus maritimus, habitat selection, Maritime pocket gopher, preference INTRODUCTION The Maritime pocket gopher (MPG, Geomys personatus maritimus) is endemic to the coastal areas of Kleberg and Nueces counties of southern Texas, between Baffin Bay and Flour Bluff (Williams and Genoways 1981). -

State Buffel Grass Strategic Plan

SOUTH AUSTRALIA Buffel Grass Strategic Plan 2019–2024 1 Suggested citation: Biosecurity SA (2019) South Australia Buffel Grass Strategic Plan 2019–2024: A plan to reduce the weed threat of buffel grass in South Australia. Government of South Australia. Edited by: Troy Bowman, David Cooke and Ross Meffin, Biosecurity SA (Department of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia). Contributors: Tim Reynolds, Ben Shepherd (editors 2012 Strategic Plan). Mark Anderson, Brett Backhouse, Doug Bickerton, Troy Bowman, David Cooke, Dwayne Godfrey, Kym Haebich, Michaela Heinson, Paul Hodges, Amy Ide, Susan Ivory, Rob Langley, Glen Norris, Greg Patrick, John Read, Grant Roberts, Ellen Ryan-Colton, Andrea Schirner, Carolina Galindez Silva, Jarrod Spencer, Clint Taylor (Buffel Grass Taskforce). Cover photo: Dense buffel grass infested hills and plains near Umuwa, APY Lands, Troy Bowman, PIRSA Foreword Buffel grass can affect biodiversity, natural and cultural heritage, communities and infrastructure. Through changes in vegetation structure and the loss of native flora and fauna, it can transform rangeland landscapes. By degrading the environment it can threaten natural, Aboriginal and European cultural heritage; remote communities and infrastructure can be impacted through the increased risk of bushfire. South Australia took the lead in 2015 as the first jurisdiction in Australia to declare buffel grass under its weed management legislation. Our response to buffel grass in South Australia requires a delicate balance between its use as a pasture grass across state and territory boundaries, and the need to protect our environment, cultural landscapes and infrastructure. The South Australian Buffel Grass Strategic Plan for 2019–24 presents a coordinated statewide approach to buffel grass management, building on the success of the 2012–2017 plan and further developing the existing zoning scheme and management strategies. -

The Ecology of Lizard Reproductive Output

Global Ecology and Biogeography, (Global Ecol. Biogeogr.) (2011) ••, ••–•• RESEARCH The ecology of lizard reproductive PAPER outputgeb_700 1..11 Shai Meiri1*, James H. Brown2 and Richard M. Sibly3 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Biology, Aim We provide a new quantitative analysis of lizard reproductive ecology. Com- University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA and Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde parative studies of lizard reproduction to date have usually considered life-history Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA, 3School components separately. Instead, we examine the rate of production (productivity of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, hereafter) calculated as the total mass of offspring produced in a year. We test ReadingRG6 6AS, UK whether productivity is influenced by proxies of adult mortality rates such as insularity and fossorial habits, by measures of temperature such as environmental and body temperatures, mode of reproduction and activity times, and by environ- mental productivity and diet. We further examine whether low productivity is linked to high extinction risk. Location World-wide. Methods We assembled a database containing 551 lizard species, their phyloge- netic relationships and multiple life history and ecological variables from the lit- erature. We use phylogenetically informed statistical models to estimate the factors related to lizard productivity. Results Some, but not all, predictions of metabolic and life-history theories are supported. When analysed separately, clutch size, relative clutch mass and brood frequency are poorly correlated with body mass, but their product – productivity – is well correlated with mass. The allometry of productivity scales similarly to metabolic rate, suggesting that a constant fraction of assimilated energy is allocated to production irrespective of body size.