State Buffel Grass Strategic Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Density, Distribution and Habitat Requirements for the Ozark Pocket Gopher (Geomys Bursarius Ozarkensis)

DENSITY, DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT REQUIREMENTS FOR THE OZARK POCKET GOPHER (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis) Audrey Allbach Kershen, B. S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Kenneth L. Dickson, Co-Major Professor Douglas A. Elrod, Co-Major Professor Thomas L. Beitinger, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kershen, Audrey Allbach, Density, distribution and habitat requirements for the Ozark pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis). Master of Science (Environmental Science), May 2004, 67 pp., 6 tables, 6 figures, 69 references. A new subspecies of the plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius ozarkensis), located in the Ozark Mountains of north central Arkansas, was recently described by Elrod et al. (2000). Current range for G. b. ozarkensis was established, habitat preference was assessed by analyzing soil samples, vegetation and distance to stream and potential pocket gopher habitat within the current range was identified. A census technique was used to estimate a total density of 3, 564 pocket gophers. Through automobile and aerial survey 51 known fields of inhabitance were located extending the range slightly. Soil analyses indicated loamy sand as the most common texture with a slightly acidic pH and a broad range of values for other measured soil parameters and 21 families of vegetation were identified. All inhabited fields were located within an average of 107.2m from waterways and over 1,600 hectares of possible suitable habitat was identified. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Appreciation is extended to the members of my committee, Dr. Kenneth Dickson, Dr. Douglas Elrod and Dr. -

(Poaceae: Paniceae), with Lectotypification of Panicum Divisum

Phytotaxa 181 (1): 059–060 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.181.1.5 A new combination in Cenchrus (Poaceae: Paniceae), with lectotypification of Panicum divisum FILIP VERLOOVE1, RAFAËL GOVAERTS2 & KARL PETER BUTTLER3 1Botanic Garden of Meise, Nieuwelaan 38, B-1860 Meise, Belgium [[email protected]] 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, England [[email protected]] 3Orber Straße 38, D-60386 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [[email protected]] Abstract The new combination, Cenchrus divisus (J.F. Gmelin) Verloove, Govaerts & Buttler, is proposed for the species widely known as Pennisetum divisum (J.F. Gmelin) Henrard, and a lectotype for Panicum divisum J.F. Gmelin is designated. Key words: Cenchrus, lectotypification, nomenclature, Panicum As a result of recent molecular phylogenetic studies the generic boundaries of Cenchrus L. and related genera have considerably changed. Donadio et al. (2009) found that Cenchrus and Pennisetum Rich. are very closely related and demonstrated that most species of Cenchrus are in fact nested in Pennisetum. Chemisquy et al. (2010) confirmed these results and recommended merging both genera. The generic name Cenchrus having priority, all species of Pennisetum needed to be transferred to Cenchrus. Morrone (in Chemisquy et al., 2010) published new combinations in Cenchrus for most of the species and Symon (2010) made some additional name changes for a few Australian taxa. The correct names in Cenchrus for all but one of the 15 Pennisetum species in Europe and the Mediterranean area, including four new combinations, were given in Verloove (2012). -

Recognise the Important Grasses

Recognise the important grasses Desirable perennial grasses Black speargrass Heteropogon contortus - Birdwood buffel Cenchrus setiger Buffel grass Cenchrus ciliaris Cloncury buffel Cenchrus pennisetijormis Desert bluegrass Bothriochloa ewartiana - Forest bluegrass Bothriochloa bladhii - Giant speargrass Heteropogon triticeus - Gulf or curly bluegrass Dichanthiumjecundum - Indian couch Bothriochloa pertusa + Kangaroo grass Themeda triandra - Mitchell grass, barley Astrebla pectinata Mitchell grass, bull Astrebla squarrosa Mitchell grass, hoop Astrebla elymoides Plume sorghum Sorghum plumosum + Sabi grass Urochloa mosambicensis - Silky browntop Eulalia aurea (E. julva) - +" Wild rice Oryza australiensis Intermediate value grasses (perennials and annuals) Barbwire grass Cymbopogon rejractus Bottle washer or limestone grass Enneapogon polyphyllus + Early spring grass Eriochloa procera + Fire grass Schizachyrium spp. Flinders grass Iseilema spp. + Ribbon grass Chrysopogon jallax Liverseed Urochloa panico ides + Love grasses Eragrostis species + Pitted bluegrass Bothriochloa decipiens Annual sorghum Sorghum timorense Red natal grass Melinis repens (Rhynchelytrum) + Rice grass Xerochloa imburbis Salt water couch Sporobolus virginicus Spinifex, soft Triodia pungens Spinifex, curly Triodia bitextusa (Plectrachne pungens) Spiny mud grass Pseudoraphis spinescens White grass Sehima nervosum Wanderrie grass Eriachne spp. Native millet Panicum decompositum + Annual and less desirable grasses Asbestos grass Pennisetum basedowii Button grass Dacty loctenium -

3 Invasive Species in the Sonoran Desert Region

3 Invasive Species in the Sonoran Desert Region 11 INVASIVE SPECIES IN THE SONORAN DESERT REGION Invasive species are altering the ecosystems of the Sonoran Desert Region. Native plants have been displaced resulting in radically different habitats and food for wildlife. Species like red brome and buffelgrass have become dense enough in many areas to carry fire in the late spring and early summer. Sonoran Desert plants such as saguaros, palo verdes and many others are not fire- adapted and do not survive these fires. The number of non-native species tends to be lowest in natural areas of the Sonoran Desert and highest in the most disturbed and degraded habitats. However, species that are unusually aggressive and well adapted do invade natural areas. In the mid 1900’s, there were approximately 146 non-native plant species (5.7% of the total flora) in the Sonoran Desert. Now non-natives comprise nearly 10% of the Sonoran Desert flora overall. In highly disturbed areas, the majority of species are frequently non-native invasives. These numbers continue to increase. It is crucial that we monitor, control, and eradicate invasive species that are already here. We must also consider the various vectors of dispersal for invasive species that have not yet arrived in Arizona, but are likely to be here in the near future. Early detection and reporting is vital to prevent the spread of existing invasives and keep other invasives from arriving and establishing. This is the premise of the INVADERS of the Sonoran Desert Region program at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. -

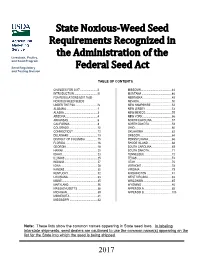

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Federal Seed Act

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Livestock, Poultry, and Seed Program Seed Regulatory Federal Seed Act and Testing Division TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGES FOR 2017 ........................ II MISSOURI ........................................... 44 INTRODUCTION ................................. III MONTANA .......................................... 46 FSA REGULATIONS §201.16(B) NEBRASKA ......................................... 48 NOXIOUS-WEED SEEDS NEVADA .............................................. 50 UNDER THE FSA ............................... IV NEW HAMPSHIRE ............................. 52 ALABAMA ............................................ 1 NEW JERSEY ..................................... 53 ALASKA ............................................... 3 NEW MEXICO ..................................... 55 ARIZONA ............................................. 4 NEW YORK ......................................... 56 ARKANSAS ......................................... 6 NORTH CAROLINA ............................ 57 CALIFORNIA ....................................... 8 NORTH DAKOTA ............................... 59 COLORADO ........................................ 10 OHIO .................................................... 60 CONNECTICUT .................................. 12 OKLAHOMA ........................................ 62 DELAWARE ........................................ 13 OREGON............................................. 64 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ................. 15 PENNSYLVANIA................................ -

ECOSYSTEM DEGRADATION, HABITAT LOSS and SPECIES DECLINE in ARID and SEMI-ARID AUSTRALIA DUE to the INVASION of BUFFEL GRASS (Cenchrus Ciliaris and C

THREAT ABATEMENT ADVICE FOR ECOSYSTEM DEGRADATION, HABITAT LOSS AND SPECIES DECLINE IN ARID AND SEMI-ARID AUSTRALIA DUE TO THE INVASION OF BUFFEL GRASS (Cenchrus ciliaris AND C. pennisetiformis) This threat abatement advice reflects the best available information at the time of development (October 2014) Last updated April 2015 To provide information updates please email [email protected] Purpose The purpose of this threat abatement advice is to identify key actions and research to abate the threat of ecosystem degradation, habitat loss and species decline in arid and semi-arid Australia due to the invasion of buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris and C. pennisetiformis1). Buffel grass comprises a suite of species and ecotypes native to Africa, Western and Southern Asia that are now rapidly colonising arid ecosystems in Australia. Abatement of this threat can help ensure the conservation of biodiversity assets including threatened species and ecological communities listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), Ramsar sites and properties on the World Heritage List. Other significant assets such as Indigenous cultural sites, state and territory listed assets and remnant vegetation would also be better protected. This advice provides information and guidance for stakeholders at national, state, regional and local levels. It suggests on-ground activities that can be implemented by local communities, natural resource management groups or interested individuals such as landholders. It also suggests actions that can be undertaken by government agencies, local councils, research organisations, industry bodies or non-government organisations. The intention of this advice is to highlight those actions considered through consultation to be of highest priority and which may be feasible, rather than to comprehensively list all actions which may abate the threat and impacts posed by buffel grass. -

Habitat Characteristics That Influence Maritime Pocket Gopher Densities

The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 26:14-24 (2013) 14 © Agricultural Consortium of Texas Habitat Characteristics That Influence Maritime Pocket Gopher Densities Jorge D. Cortez1 Scott E. Henke*,1 Richard Riddle2 1Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, MSC 218, Texas A&M University- Kingsville, Kingsville, TX 78363 2United States Navy, 8851 Ocean Drive, Corpus Christi, TX 78419-5226 ABSTRACT The Maritime pocket gopher (Geomys personatus maritimus) is a subspecies of Texas pocket gopher endemic to the Flour Bluff area of coastal southern Texas. Little is known about the habitat and nutritional requirements of this subspecies. The amount and quality of habitat necessary to sustain Maritime pocket gophers has not been studied. Our objectives were to assess the habitat, vegetation, and nutritional parameters available to Maritime pocket gophers at four different levels of gopher mound density. We chose study sites with zero, low (25-50 mounds/ha), intermediate (75-150 mounds/ha), and high (>200 mounds/ha) gopher mound densities. Vegetation and soil samples were collected using 0.25 m2 quadrats; vegetation was divided into above- and below-ground biomass for analysis. Maritime pocket gophers avoided areas of clay soils with high levels of calcium, magnesium, sulfur, and sodium compounds. A direct relationship existed between gopher activity within an area and vegetation biomass. However, nutritional quality of an area did not appear to be a determining factor for the presence of Maritime pocket gophers. KEY WORDS: Population density, Geomys personatus maritimus, habitat selection, Maritime pocket gopher, preference INTRODUCTION The Maritime pocket gopher (MPG, Geomys personatus maritimus) is endemic to the coastal areas of Kleberg and Nueces counties of southern Texas, between Baffin Bay and Flour Bluff (Williams and Genoways 1981). -

REVISED DRAFT Round-Leaved Chaff Flower (Achyranthes Splendens Var

REVISED DRAFT Round-Leaved Chaff Flower (Achyranthes splendens var. rotundata) Habitat Conservation Plan Kenai Industrial Park Project Prepared for: Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources Applicant: CIRI Land Development Company 2525 C Street, Suite 500 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 Draft prepared by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. 23049 Ualena Street, Suite 1100 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96819 Revisions and final document produced by: SWCA Environmental Consultants, Honolulu Office Bishop Square: ASB Tower 1001 Bishop Street, Suite 2800 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813 June 2013 REVISED DRAFT Round-Leaved Chaff Flower HCP; Kenai Industrial Park This page intentionally left blank 2013 SWCA Environmental Consultants REVISED DRAFT ROUND-LEAVED CHAFF FLOWER (ACHYRANTHES SPLENDENS VAR. ROTUNDATA) HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN KENAI INDUSTRIAL PARK PROJECT PREPARED FOR: Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources APPLICANT: CIRI Land Development Company 2525 C Street, Suite 500 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 DRAFT PREPARED BY: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. 3049 Ualena Street, Suite 1100 Honolulu, HI. 96819 REVISIONS AND FINAL DOCUMENT PRODUCED BY: SWCA Environmental Consultants Honolulu Office Bishop Square: ASB Tower 1001 Bishop Street, Suite 2800 Honolulu, HI. 96813 June 2013 REVISED DRAFT Round-Leaved Chaff Flower HCP; Kenai Industrial Park This page intentionally left blank 2013 SWCA Environmental Consultants REVISED DRAFT Round-Leaved Chaff Flower HCP; Kenai Industrial Park TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT OVERVIEW............................................................................ -

Mnesithea Granularis

Check List 10(2): 374–375, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution N Mnesithea granularis ISTRIBUTIO (L.) Koning & Sosef: A New Record to D the flora of the Malwa Region, India RAPHIC G K. L. Meena EO [email protected] Department of Botany, MLV Government College, Bhilwara (Rajasthan) - 311 001. G N E- mail: O Abstract: A new record of Mnesithea granularis OTES N (L.) Koning & Sosef (Poaceae), collected for the first time from Malwa region (Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan) India is presented. A detail description, up to date nomenclature, phenology, ecological notes and illustrations of this species have been presented. Between 2008 and 2012 botanical surveys were polystachya Hackelochloa granularis collections were acquired from the Malwa region, India. P. Beauv., Fl. Owar & Benin.Mnisuris 1: 24,porifera t. 14. 1805.Hack. undertaken in southern Rajasthan, where significant plant (L.) O. Ktze. Rev. Hook, Gen. f. op. Pl. cit 2: 776. Hackelochloa1891; Bor, Grass porifera Ind. 159. 1960. Geographically, the Malwa region is situated between in Oesterr. op.Bot. cit. Zeitschr.Rytilix 41: 48. granularis 1891; . 160. and21°10′N south-eastern to 25°09′ Rajasthan.N Latitude After and 73°45′a thorough E to survey79°13′ ofE (Hack.) Rhind, Grass. Burma 77. theLongitude literature, and critical a plateau examination in western of collectedMadhya materialPradesh 1945; Bor, 160. (L.) Skeels in U. S. Dept. Agric., Bur. Pl. Indus. 282: 20. 1913. (Figures 1 and 2). determinedand with expert as Mnesithea advice fromgranularis authorities of the Indian Annual, erect, up to 30 cm high; culms much branched Association of Angiosperm Taxonomy, several specimens from base, nodes hairy. -

Genetic Diversification Among Populations of the Endangered Hawaiian Endemic Euphorbia Kuwaleana (Euphorbiaceae)

Genetic diversification among populations of the endangered Hawaiian endemic Euphorbia kuwaleana (Euphorbiaceae) By: Clifford W. Morden*, Troy Hiramoto, and Mitsuko Yorkston Abstract The Hawaiian Euphorbia is an assemblage of 17 species, seven of which are endangered and four others rare. Euphorbia kuwaleana is an endangered species of small shrubs restricted to three small populations in west O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. The species has declined to fewer than 1000 individuals largely due to habitat encroachment by alien plant species and the periodic fires that occur in the vicinity. Genetic variation was assessed among individuals in two populations to determine what impact small population size has had on genetic diversity within the species using RAPD markers. Results demonstrate that polymorphism within these populations is high (mean=82.5%), equal to or exceeding that of many other non-endangered Hawaiian species. Genetic similarities within (0.741) and among (0.716) populations, FST (0.072), and PCO analysis all indicate differentiation among the populations although in close geographical proximity (<1 km apart). Conservation efforts for this species should focus on protection of existing populations from eminent threats and the establishment of new populations in suitable habitats on O‘ahu. *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Pacific Science, vol. 68, no. 1 July 16, 2013 (Early view) Introduction The genus Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) is represented in Hawaii by 17 species from two separate colonizations. The C3 species, Euphorbia haeleeleana, is a tree with succulent stems and is closely related to the Australian succulent species E. plumerioides and E. sarcostemmoides (Zimmerman et al 2010). The other 16 species (previously in the genus Chamaesyce, now recognized as a subgenus of Euphorbia; Yang et al. -

Grasses and Grasslands

Grasses and Grasslands – Sensitization on the • Characteristics • Identification • Ecology • Utilisation Of Grasses by MANOJ CHANDRAN IFS Chief Conservator of Forests Govt. of Uttarakhand Grasses and Grasslands • Grass – A member of Family Poaceae • Cyperaceae- Sedges • Juncaceae - Rushes • Grassland – A vegetation community predominated by herbs and other grass or grass like plants including undergrowth trees. Temperate and Tropical Grasslands • Prairies • Pampas • Steppes • Veldt • Savanna Major Grassland types (old classification) • Dabadghao & Shankarnarayan (1973) – Sehima – Dichanthium type – Dichanthium - Cenchrus – Lasiurus type – Phragmites – Saccharum – Imperata type – Themeda – Arundinella type – Cymbopogon – Pennisetum type – Danthonia – Poa type Revised Grassland Types of India (2015) 1. Coastal Grasslands 2. Riverine Alluvial Grasslands 3. Montane Grasslands 4. Sub-Himalayan Tall Grasslands of Terai region 5. Tropical Savannas 6. Wet Grasslands Grassland types of India 1- Coastal grasslands – Sea beaches (mainland and islands) – Salt marshes – Mangrove grasslands Sea beach grasslands, Spinifex littoreus Salt marsh grasslands, Rann of Kutch 2. Riverine Alluvial grasslands Corbett NP, Katerniaghat WLS 3. Montane grasslands – Himalayan subtropical grasslands – Himalayan temperate grasslands – Alpine meadows – Trans-himalayan Steppes – Grasslands of North East Hills – Grasslands of Central Highlands – Western Ghats • Plateaus of North WG, Shola grasslands and South WG – Eastern ghats – Montane Bamboo brakes Alpine meadows, Kedarnath Alpine meadows Mamla/Ficchi – Danthonia cachemyriana Cordyceps sinensis – Yar-tsa Gam-bu Annual Migration Montane grasslands of NE Hills, Dzukou valley Montane bamboo brakes of Dzukou valley, Nagaland Shola Grasslands, South Western Ghats Pine forest grasslands, Uttarakhand Central Highlands, Pachmarhi, MP Trans-Himalayan Steppes Grazing in trans-Himalayan steppe Tibetan steppe, Mansarovar Tibetan steppe 4. Sub-himalayan Tall Grasslands of Terai Region 5. -

Tools for Improved Management of Buffelgrass in the Sonoran Desert

Tools for Improved Management of Buffelgrass in the Sonoran Desert Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Bean, Travis M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 16:27:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/325503 TOOLS FOR IMPROVED MANAGEMENT OF BUFFELGRASS IN THE SONORAN DESERT by Travis Maclain Bean __________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Travis Bean, titled Tools for improved management of buffelgrass in the Sonoran Desert and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 3 June 2014 Steven E. Smith _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 3 June 2014 Martin M. Karpiscak _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 3 June 2014 Shirley