Towards Effective Protected Area Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing Nationally Determined Contributions Through Protected Areas Table of Contents

ENHANCING NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTIONS THROUGH PROTECTED AREAS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 BACKGROUND 5 METHODOLOGY 7 RESULTS 13 1. EXPLICIT MENTION OF PROTECTED AREAS 13 2. ESTABLISHING NEW OR EXPANDING EXISTING PROTECTED AREAS 14 3. UTILIZING PROTECTED AREAS TO HELP PEOPLE ADAPT TO CLIMATE CHANGE (ECOSYSTEM-BASED ADAPTATION) 15 4. MITIGATION BENEFITS FROM CARBON SEQUESTRATION AND AUTHORS AVOIDED EMISSIONS 17 Abigail Hehmeyer, Jacqueline Vogel, Shaun Martin, Ryan Bartlett 5. MANAGING PROTECTED AREAS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS 18 DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 20 WWF CONCLUSION 27 GLOSSARY 28 For more than 50 years, WWF has been protecting the future of nature. One APPENDICES 31 of the world’s leading conservation organizations, WWF works in nearly 100 countries and is supported by more than 1.1 million members in the United APPENDIX 1: RESULTS BY COUNTRY 31 States and 5 million supporters globally. WWF’s unique way of working APPENDIX 2: COUNTRIES RANKED BY CREDITS EARNED FOR THE combines global reach with a foundation in science, involves action at every level 5 CRITERIA EXAMINED 39 from local to global, and ensures the delivery of innovative solutions that meet the needs of both people and nature. Visit worldwildlife.org to learn more. APPENDIX 3: COUNTRIES REFERENCED IN THIS REPORT, LISTED BY REGION 41 REFERENCES 43 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this analysis, conducted by WWF US, was made possible by the Support Project for the Implementation of the Paris Agreement (SPA), which is implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) under its International Climate Initiative (IKI). -

What Is Inclusive Conservation and Why Is It Important to Biodiversity Conservation and Protected Area Management?

Fact Sheet What is inclusive conservation and why is it important to biodiversity conservation and protected area management? October 2019 ‘Inclusive Conservation’ is a trans-disciplinary approach to balancing stakeholder visions, and promoting shared agreements for the future management of protected areas through the development and application of multiple tools and processes. - 2 - Protecting our natural areas Global context Protected areas are clearly defined geographical spaces, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated Figure 1: Growth in ecosystem services and cultural values.1 Protected areas are critical for protected area coverage conserving local to regional biodiversity, particularly the characteristic on land and in the ocean (Exclusive Economic Zones of threatened species, habitats and ecosystems.2,3 (EEZ) and Areas Beyond At a global level, Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) National Jurisdiction (ABNJ)) between 1990 agreed in 2010 to a target of protecting at least 17% of terrestrial and and 2018 and projected inland water areas, and 10% of coastal and marine areas (Aichi Target growth to 2020 according 11), by 2020. Currently, protected areas cover almost 15% of land and to commitments from countries and territories.5 inland waters and 8% of the world’s oceans.4 (Figure 1). Area (Million km2) 40 2 30 3 20 10 1 0 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 1 ABNJ 2 EEZ 3 Land - 3 - Despite this expansion, protected areas only partly cover important sites for biodiversity, and there are issues associated with their ecological representativeness and equitable management6. -

Policy Highlights Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes

Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes Policy HIGHLIGHTS Marine Protected Areas Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes Progress in expanding the coverage of marine protected areas is underway. With a push from the Sustainable Development Goals their global coverage is expected to increase even further. But their effectiveness is uneven. It is one thing to draw a line on a map – it is another to effectively design, site, monitor and enforce them. We are starting to understand what works and what doesn’t. Adaptive management and improvements over time will be essential if marine conservation and sustainable use objectives are to be met. Simon Upton – OECD Environment Director POLICY HI G HLI G H T Pressures on marine ecosystems from human activities are already severe and the often S competing demands for marine space and resources are projected to rise. Costs of poor ocean management practices include environmental and social costs that are often not factored into decision-making processes. This undermines the resilience of the ecosystems upon which we depend, for food, for income, but also other less visible life-support functions such as coastal protection, habitat provisioning and carbon sequestration. Marine protected areas are one of the policy instruments available to help ensure the conservation and sustainable use of our vast yet vulnerable ecosystems. While progress is being made towards increasing the global coverage of marine protected areas, significantly greater efforts are needed to ensure these are also being located in areas that are under threat and can therefore yield greatest environmental benefits, and that they are effectively managed. -

Understanding and Assessing Equity in Protected Area Conservation a Matter of Governance, Rights, Social Impacts and Human Wellbeing

Understanding and assessing equity in protected area conservation A matter of governance, rights, social impacts and human wellbeing Phil Franks, Francesca Booker and Dilys Roe Issue Paper Biodiversity; Governance Keywords: February 2018 Equity, conservation, protected areas, Social Assessment of Protected Areas (SAPA), wellbeing About the author Phil Franks is a senior researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Francesca Booker is a researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Dilys Roe is a principal researcher in the biodiversity team at IIED. Corresponding author: Phil Franks, [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Natural Resources Group The aim of the Natural Resources Group is to build partnerships, capacity and wise decision-making for fair and sustainable use of natural resources. Our priority in pursuing this purpose is on local control and management of natural resources and other ecosystems. Acknowledgments This paper builds on the work of a large group of people who have worked over the last three years on the development of the equity framework for protected area management and governance. Annex 1 contains the latest version of this framework at the time of publication, which reflects discussions at a workshop in April 2017 and a recent round of comments. We would like to acknowledge, in particular, the contribution of Kate Schreckenberg and Adrian Martin (co-authors of our earlier publications), staff of the Forest Peoples’ Programme for their detailed comments on the latest version of the framework, and Noelia Zafro-Calvo for being the first person to put the framework to good use. Published by IIED, February 2018 Franks, P et al. -

India's Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological

India’s Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity March, 2012 Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point: Dr. Vinod B. Mathur, D.Phil. (Oxon.) Dean, Faculty of Wildlife Sciences, Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun (Uttarakhand). INDIA Tel.: +91‐(0)135‐2640304(Off.); Mob.: +9412054648 Fax: +91‐(0)135‐2640117; Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Lead implementing agency: Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India Multistakeholder committee: 1. National Board for Wildlife under the Chairmanship of Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2. State Boards for Wildlife under the Chairmanship of respective Chief Minister of States Description of protected area system National Targets and Vision for Protected Areas The target 11 of the Aichi Targets indicates that by 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10% of coastal and marine areas especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services are conserved through protected areas and other effective area‐based conservation measures; are effectively and equitably managed; are ecologically representative; and are well connected systems of PAs integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes. India’s National Wildlife Action Plan (2006‐2011) envisages 10% of the geographical area of the country under PA coverage. Recommendations are in place to establish additional 67 new National Parks at 203 new Wildlife Sanctuaries to make PA network more geographically representatives. Efforts are also underway to establish new ‘Marine Protected Areas’. In India, all government owned forests and other important ecosystems (which are outside the legally designated PA network), and occupy ca. -

Coastal and Marine Protected Areas in India: Envis Bulletin Challenges and Way Forward 50 51 Wildlife and Protected Areas

Coastal And Marine Protected Areas In India: envis bulletin Challenges And Way Forward 50 51 Wildlife and Protected Areas Summary India has an extensive coastline of 7517 km length, of which 5423 km is in peninsular India and 2094 km is in the 02 2 Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands. The EEZ has an extent of 2.02 million km . This coastline also supports a huge human population, which is dependent on the rich coastal and marine resources. Despite the tremendous ecological and economic importance and the existence of a policy and regulatory framework, India's coastal and marine ecosystems are under threat. Numerous direct and indirect pressures arising from different types of economic development and associated activities are having adverse impacts on the coastal and marine biodiversity across the country. The marine protected area network in India has been used as a tool to manage natural marine resources for biodiversity conservation and for the well-being of people dependent on it. Scientific monitoring and traditional observations confirm that depleted natural marine resources are getting restored and/or pristine ecological conditions have been sustained in well managed MPAs. There are 24 MPAs in peninsular India and more than 100 MPAs in the country's islands. The 24 MPAs of the mainland have a total area of about 8214 km2, which is about 5% of the total protected area network of India and represents 0.25% of the total geographic area of the country. Dedicated efforts are required to secure and strengthen community participation in managing the marine protected area network in India. -

Park Guards in the Conservation of Protected Areas Angela Martin

park guards in the conservation of protected areas Angela Martin Parks in Peril, Innovations in Conservation Series, 2007 Park guards are the field staff in charge of the protection and security of natural resources in a protected area (Núñez, 2005). Depending on the specific character- istics of the protected area, they are also in charge of safeguarding cultural resources (PROARCA/APM, 2004). Without their presence, protected areas are more vul- nerable to the factors threatening their integrity. Park guards may be employed by government or civil society institutions, (using their own or donors’ resources), or work as volunteers. Support for park guards and their work is considered a key component for the Hugo Arnal strengthening of protected areas. This includes the provision of essential equipment for their operations, such as vehicles, radios and uniforms, as well as training. Accord- ing to a 1998 study done for the Parks in Peril (PiP) program, the most effective way to engage communities in management activities was to hire them as guards for the areas (Brandon et al, 1998). PiP has consequently promoted participatory processes in this issue... as a way of involving the community and encouraging local residents to become guides • General characteristics of park or park guards, on a paid or volunteer basis. Also, PiP encouraged government agen- guards cies to facilitate patrolling and training for park guards and transfer authority to local actors (Martin and Rieger, 2003). • Innovative strategies with park guards The purpose of this bulletin is to present general elements about the characteristics, - Community, indigenous and roles and responsibilities of the park guards in the protected areas, emphasizing some volunteer park guards innovative strategies from which lessons can be derived. -

Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation I: Reserve Planning and Design

Network of Conservation Educators & Practitioners Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation I: Reserve Planning and Design Author(s): Eugenia Naro-Maciel, Eleanor J. Stering, and Madhu Rao Source: Lessons in Conservation, Vol. 2, pp. 19-49 Published by: Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners, Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History Stable URL: ncep.amnh.org/linc/ This article is featured in Lessons in Conservation, the official journal of the Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners (NCEP). NCEP is a collaborative project of the American Museum of Natural History’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (CBC) and a number of institutions and individuals around the world. Lessons in Conservation is designed to introduce NCEP teaching and learning resources (or “modules”) to a broad audience. NCEP modules are designed for undergraduate and professional level education. These modules—and many more on a variety of conservation topics—are available for free download at our website, ncep.amnh.org. To learn more about NCEP, visit our website: ncep.amnh.org. All reproduction or distribution must provide full citation of the original work and provide a copyright notice as follows: “Copyright 2008, by the authors of the material and the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation of the American Museum of Natural History. All rights reserved.” Illustrations obtained from the American Museum of Natural History’s library: images.library.amnh.org/digital/ SYNTHESIS 19 Protected Areas and Biodiversity Conservation I: Reserve Planning and Design Eugenia Naro-Maciel,* Eleanor J. Stering, † and Madhu Rao ‡ * The American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, U.S.A., email [email protected] † The American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, U.S.A., email [email protected] ‡ Wildlife Conservation Society, New York, NY, U.S.A., email [email protected] Source: K. -

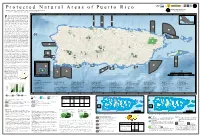

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Designing Protected Areas for Social–Ecological Sustainability: Effectiveness of Management Guidelines for Preserving Cultural

sustainability Article Designing Protected Areas for Social–Ecological Sustainability: Effectiveness of Management Guidelines for Preserving Cultural Landscapes Patricio Sarmiento-Mateos 1,*, Cecilia Arnaiz-Schmitz 2, Cristina Herrero-Jáuregui 1, Francisco D. Pineda 1 and María F. Schmitz 1 1 Department of Biodiversity, Ecology and Evolution, Complutense University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (C.H-J.); [email protected] (F.D.P.); [email protected] (M.F.S.) 2 Social-ecological Systems Laboratory, Department of Ecology, Autonomous University of Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 April 2019; Accepted: 16 May 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: Rural cultural landscapes are social–ecological systems that have been shaped by traditional human land uses in a co-evolution process between nature and culture. Protected areas should be an effective way to protect cultural landscapes and support the way of life and the economy of the local population. However, nature conservation policymaking processes and management guidelines frequently do not take culturalness into account. Through a new quantitative approach, this paper analyzes the regulatory framework of two protected areas under different management categories, located in an ancient cultural landscape of the Madrid Region (Central Spain), to identify the similarities in their conservation commitments and the effectiveness of their zoning schemes. The results show some arbitrariness in the design and management of these parks, highlighting the importance of prohibited measures in their zoning schemes that encourage uses and activities more related to naturalness than to culturalness. The recognition of protected areas as cultural landscapes and their management considering both naturalness and culturalness issues are important methods of better achieving sustainable management objectives from a social–ecological approach. -

Marine Protection in America's Ocean

SeaStates 2021 Marine Protection in America’s Ocean MARINE PROTECTION ATLAS SeaStates 2021 Marine Protection in America’s Ocean SeaStates 2021 Marine Protection in America’s Ocean SeaStates 2021 is a rigorous, quantitative accounting of fully and words marine reserve or marine protected area are used. Protect- strongly protected MPAs in America’s ocean updated annually by ing biodiversity in marine reserves increases the abundance and Sardines swirl amongst giant kelp off Anacapa Island, part the team at MPAtlas.org. First published in 2013, our annual reports diversity of marine life inside the reserve and typically results in of the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Federal are intended to measure US progress as a whole, and state prog- the export of marine life to surrounding areas4,5. In short, no-take and state authorities co-manage the MPA complex in the Channel Islands which includes a network of fully protected ress towards effective marine protection in their coastal waters. MPAs effectively protect marine life, can secure food resources areas surrounded by the highly protected sanctuary zone. Oceans are essential to human survival and prosperity, yet our for millions of people by exporting fish outside the MPA, and Marine Conservation Institute has recognized the Northern Channel Islands with a platinum-level Blue Parks award. activities are damaging many ecosystems and pushing numerous prevent loss of species. Strongly protected areas are those in (credit Robert Schwemmer, NOAA) critical marine species toward extinction1. Many marine biologists which extraction is quite limited and conservation benefits are high but not as high as fully protected areas. -

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas

Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Guidelines for Marine MPAs are needed in all parts of the world – but it is vital to get the support Protected Areas of local communities Edited and coordinated by Graeme Kelleher Adrian Phillips, Series Editor IUCN Protected Areas Programme IUCN Publications Services Unit Rue Mauverney 28 219c Huntingdon Road CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK Tel: + 41 22 999 00 01 Tel: + 44 1223 277894 Fax: + 41 22 999 00 15 Fax: + 44 1223 277175 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 3 IUCN The World Conservation Union The World Conservation Union CZM-Centre These Guidelines are designed to be used in association with other publications which cover relevant subjects in greater detail. In particular, users are encouraged to refer to the following: Case studies of MPAs and their Volume 8, No 2 of PARKS magazine (1998) contributions to fisheries Existing MPAs and priorities for A Global Representative System of Marine establishment and management Protected Areas, edited by Graeme Kelleher, Chris Bleakley and Sue Wells. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, The World Bank, and IUCN. 4 vols. 1995 Planning and managing MPAs Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers, edited by R.V. Salm and J.R. Clark. IUCN, 1984. Integrated ecosystem management The Contributions of Science to Integrated Coastal Management. GESAMP, 1996 Systems design of protected areas National System Planning for Protected Areas, by Adrian G. Davey. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No.