Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Embedded Digital Musical Instruments

A Framework for Embedded Digital Musical Instruments Ivan Franco Music Technology Area Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © 2019 Ivan Franco 2019/04/11 i Abstract Gestural controllers allow musicians to use computers as digital musical instruments (DMI). The body gestures of the performer are captured by sensors on the controller and sent as digital control data to a audio synthesis software. Until now DMIs have been largely dependent on the computing power of desktop and laptop computers but the most recent generations of single-board computers have enough processing power to satisfy the requirements of many DMIs. The advantage of those single-board computers over traditional computers is that they are much smaller in size. They can be easily embedded inside the body of the controller and used to create fully integrated and self-contained DMIs. This dissertation examines various applications of embedded computing technologies in DMIs. First we describe the history of DMIs and then expose some of the limitations associated with the use of general-purpose computers. Next we present a review on different technologies applicable to embedded DMIs and a state of the art of instruments and frameworks. Finally, we propose new technical and conceptual avenues, materialized through the Prynth framework, developed by the author and a team of collaborators during the course of this research. The Prynth framework allows instrument makers to have a solid starting point for the de- velopment of their own embedded DMIs. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Computer Music

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF COMPUTER MUSIC Edited by ROGER T. DEAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published as an Oxford University Press paperback ion Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Oxford handbook of computer music / edited by Roger T. Dean. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-979103-0 (alk. paper) i. Computer music—History and criticism. I. Dean, R. T. MI T 1.80.09 1009 i 1008046594 789.99 OXF tin Printed in the United Stares of America on acid-free paper CHAPTER 12 SENSOR-BASED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND INTERACTIVE MUSIC ATAU TANAKA MUSICIANS, composers, and instrument builders have been fascinated by the expres- sive potential of electrical and electronic technologies since the advent of electricity itself. -

Hear Me Now: the Implication and Significance of the Female Composer’S Voice As Sound Source in Her Electroacoustic Music

Hear Me Now: the implication and significance of the female composer’s voice as sound source in her electroacoustic music Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner Computing and Information Technology Center, University of North Texas [email protected] This subject also interests me as I am myself a composer Abstract of primarily text-based electroacoustic music and video works. In several instances I am the recorded female voice In her writings about the role of the female voice in on the tape. After reading Bosma’s research which is readily electroacoustic music, noted Dutch researcher Hannah available on her website, I began to think about how I had Bosma has identified a variety of issues surrounding the used my own voice in my music and also why I had done compositional choices of those utilizing spoken and sung so. The reasons range from the practical to the symbolic and text in their work and illustrated the differences of use in will be discussed later in this paper. A question from an relationship to the chosen vocalist’s gender. Bosma article reviewer about the music of Alice Shields (which I exclusively focuses upon the musical works of men in her have researched extensively) got me thinking about other studies. This paper explores how women utilize the voice in women who use their own voice in the creation of their electroacoustic music and more specifically whether their music. The result is Hear Me Now, a discussion of a very treatment of the female voice in any way differs from the small number of the many women who use their voice as the treatment of the female voice by their male counterparts. -

B Ienna Le Des M Usiq Ues Exp Lo Ra to Ires

Biennale des musiques explo ratoires DU 14 MARS AU 4 AVRIL P.2 P.3 14 MARS — 14H & 16H30 14 & 15 MARS 15 MARS 15 MARS — 18H Kurt Schwitters, Sonate 21 MARS — 20H30 SALLE DU BALLET PARVIS DE L’AUDITORIUM PERFOMANCE — 12H15 GRANDE SALLE in Urlauten, avec cadence GRANDE SALLE ATELIER — 14H À 17H de Georges Aperghis Comme La Bulle BAS-ATRIUM Morciano, Charlie Chaplin, “The Hynkel Le Papillon Noir Speech” à la radio -Environnement Veggie Orchestra Dufourt, Ravel Benjamin de La Fuente, Bypass → Tarif plein : 10€ / Tarif réduit : 5€ SON PRIMORDIAL THEÂTRE DE LA RENAISSANCE, OULLINS DU 16 AU 20 MARS — 20H PETITE SALLE Tourniquet Installée pour toute la durée Orchestre national de Lyon Playtronica Lara Morciano, Riji, AUDITORIUM du week-end, La Bulle - Un concert suivi d'un déjeuner création mondiale -ORCHESTRE Environnement accueillera et d'un atelier à expérimenter Ensemble Multilatérale NATIONAL DE LYON de courtes formes artistiques Hugues Dufourt, Ur-Geräusch en famille qui fait chanter les fruits Maurice Ravel, Boléro Les Métaboles David Jisse, conception, voix, et des ateliers pour petits et grands. et les légumes. Yann Robin, musique 13 MARS – 20H → Gratuit ! → Tarifs : de 8 à 39€ échantillons et électronique → Gratuit ! Yannick H aenel, livret GRANDE SALLE Kasper T. Toeplitz, basse Elise Chauvin, actrice-chanteuse 14 & 15 MARS — 16H30 et percussions 15 MARS — 11H → Tarifs : de 5 à 25€ SALLE PROTON Quintette pour → Tarif plein : 8€ / Tarif réduit : 5€ GRANDE SALLE ombre et LE SUCRE Marie Nachury, texte, chant et jeu 24 MARS — 20H Leading -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXTENDED FROM WHAT?: TRACING THE CONSTRUCTION, FLEXIBLE MEANING, AND CULTURAL DISCOURSES OF “EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES” A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Charissa Noble March 2019 The Dissertation of Charissa Noble is approved: Professor Leta Miller, chair Professor Amy C. Beal Professor Larry Polansky Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Charissa Noble 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgements and Dedications viii Introduction to Extended Vocal Techniques: Concepts and Practices 1 Chapter One: Reading the Trace-History of “Extended Vocal Techniques” Introduction 13 The State of EVT 16 Before EVT: A Brief Note 18 History of a Construct: In Search of EVT 20 Ted Szántó (1977): EVT in the Experimental Tradition 21 István Anhalt’s Alternative Voices (1984): Collecting and Codifying EVT 28evt in Vocal Taxonomies: EVT Diversification 32 EVT in Journalism: From the Musical Fringe to the Mainstream 42 EVT and the Classical Music Framework 51 Chapter Two: Vocal Virtuosity and Score-Based EVT Composition: Cathy Berberian, Bethany Beardslee, and EVT in the Conservatory-Oriented Prestige Economy Introduction: EVT and the “Voice-as-Instrument” Concept 53 Formalism, Voice-as-Instrument, and Prestige: Understanding EVT in Avant- Garde Music 58 Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio 62 Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt 81 Conclusion: The Plight of EVT Singers in the Avant-Garde -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

Denham Scholarly Essay.Pdf

IMPROVISATION AS A GENERATIVE TOOL FOR NEW OPERA: AN EXPLORATION OF METHODS AND PARAMETERS BY ELLEN LOUISE DENHAM SCHOLARLY ESSAY Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Sylvia Stone, Chair Professor Erik Lund, Director of Research Associate Professor Katherine Syer Assistant Professor Michael Tilley ABSTRACT This scholarly essay explores the subject of improvisation in opera and vocal music, tracing its historical antecedents, providing examples of contemporary, classically-informed improvising singers and opera companies, and presenting an overview of possible methods and parameters. Chapter 1 examines the historical background of extemporaneous counterpoint in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the flourishing of improvised ornaments and embellishments from the Baroque era to the bel canto style of the nineteenth century, and the eventual decline in the use of improvised ornaments and cadenzas in the late nineteenth century. Chapter 2 covers first the subject of contemporary improvisation, including experimental techniques from the 1950s and 1960s, with reference to the use of improvisatory elements in composed scores. The second area involves a discussion of singer-composers Cathy Berberian, Meredith Monk, Pamela Z, and Bobby McFerrin. The third area explores current opera creators and performers using improvisation, focusing on the improv-comedy-based groups Impropera and La Donna Improvvisata, and two “devised operas”: Ann Baltz’s OperaWorks production of The Discord Altar, and Ellen Lindquist’s dream seminar. Much of this newer material has yet to be the subject of much scholarship. -

Third Space Network: Theatrical Roots

Revista do Programa de Pós-graduação em Comunicação Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora / UFJF ISSN 1516-0785 | e-ISSN 1981-4070 Lumina Third Space Network: Theatrical Roots Randall Packer1 Abstract: This essay provides an overview of artistic work and experimentation leading to the concept of the Third Space Network: a live Internet broadcast and performance project for connecting artists, audiences, and cultural perspectives from around the world. The concept of the third space suggests the collapse of the local (first space) and remote (second space) into a third, socially constructed networked space. The third space can be viewed as a new realization of the community of theater in a globally connected culture: performance space for broadcasted live art, a forum for the aggregation of artist streams of media art, and an arena for social interaction. The following is a personal artistic history and contextualization of nearly thirty years of live performance, interactive media, installation, Internet art, and the spaces they inhabit. This essay connects early work in Music Theater from the late 1980s and early 1990s to more recent networked projects to frame the idea of the Third Space Network as a new theatrical environment rich in potential for live performance and creative discourse. Keywords: Media art. Creative discourse. Live performance. Networked space. Third space network. 1 MFA and PhD in music composition. Multimedia artist, composer, writer and scholar in new media. Associate Professor of Networked Artat Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Website: http://zakros.com/E-mail: [email protected]. 82 Juiz de Fora, PPGCOM – UFJF, v. 11, n. -

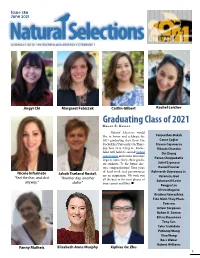

Graduating Class of 2021 M EGAN E

Issue !"# June $#$! A NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY Jingyi Chi Margaret Fabiszak Caitlin Gilbert Rachel Leicher Graduating Class of 2021 M EGAN E . KELLEY Natural Selections would like to honor and celebrate the Sanjeethan Baksh 2021 graduating class from !e Caner Çağlar Rockefeller University. On !urs- Steven Cajamarca day, June 10 at 2:30 p.m., Rocke- Vikram Chandra feller will hold its second virtual Du Cheng convocation and confer doctorate Pavan Choppakatla degrees upon thirty-three gradu- ate students. To the future doc- Juliel Espinosa tors, congratulations! Your years Daniel Firester Rohiverth Guarecuco Jr. Nicole Infarinato Jakob Træland Rostøl, of hard work and perseverance are an inspiration. We wish you “Feel the fear, and do it “Another day, another Veronica Jové all the best in the next phases of Solomon N Levin anyway.” dollar” your careers and lives. n Fangyu Liu Olivia Maguire Kristina Navrazhina Tiên Minh Thủy Phan- Everson Artem Serganov Rohan R. Soman Elitsa Stoyanova Tony Sun Taku Tsukidate Putianqi Wang Xiao Wang Ross Weber Robert Williams Fanny Matheis Elisabeth Anne Murphy Xiphias Ge Zhu ! Editorial Board Megan Elizabeth Kelley Editor-in-Chief and Managing Editor, Communication Anna Amelianchik Associate Editor Nicole Infarinato Editorial Assistant, Copy Editor, Distribution Evan Davis Copy Editor, Photographer-in-Residence PHOTO COURTESY OF METROGRAPH PICTURES Melissa Jarmel Copy Editor, Website Tra!c Sisters with Transistors Audrey Goldfarb LANA NORRIS Copy Editor, Webmaster, Website Design Women have o"en been overlooked Barron built her own circuitry, and Laurie Jennifer Einstein, Emma Garst in the history of electronic music. !eir Spiegel programmed compositional so"- Copy Editors mastery of new technology and alien ware for Macs. -

Case Studies of Women and Queer Electroacoustic Music Composers

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Music Technology, Gender, and Sexuality: Case Studies of Women and Queer Electroacoustic Music Composers Justin Thomas Massey West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Justin Thomas, "Music Technology, Gender, and Sexuality: Case Studies of Women and Queer Electroacoustic Music Composers" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7460. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7460 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Music Technology, Gender, and Sexuality: Case Studies of Women and Queer Electroacoustic Music Composers Justin T. Massey A Dissertation submitted To the College of Creative Arts At West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Saxophone Performance Michael Ibrahim, DMA, Chair Evan MacCarthy, PhD, Research Advisor Jared Sims, DMA Matthew Heap, PhD Jonah Katz, PhD School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Music Technology, Electroacoustic Music, Feminist Studies, Queer Studies, New Music, Elainie Lillios, Jess Rowland, Carolyn Borcherding Copyright © 2019 Justin T. -

MIT Sounding 2015-16 New Music Series Headliners: Maya Beiser, Keeril Makan & Jay Scheib's Persona, Johnny Gandelsman, F

MIT Sounding 2015-16 New Music Series Headliners: Maya Beiser, Keeril Makan & Jay Scheib’s Persona, Johnny Gandelsman, FLUX Quartet, Pamela Z Media Contact: Leah Talatinian Communications Manager, Arts at MIT [email protected] | 617-253-5351 | arts.mit.edu Cambridge, MA, August 13, 2015 — Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announces the 2015- 16 lineup for the innovative annual performance series MIT Sounding, curated by Evan Ziporyn. Featured performances by some of the world’s leading artists run the gamut, from Bach to Led Zeppelin and Morton Feldman, and from acoustic recitals to electronic manipulations of the human voice. The artists in this season’s MIT Sounding offer audiences new ways to regard repertoire, genre and performance practice. In the fall season, Keeril Makan and Jay Scheib reimagine Ingmar Bergman’s classic 1966 film Persona in operatic form; classical cellist Maya Beiser reinterprets the rock canon in “Uncovered”; and violinist Johnny Gandelsman reprises his powerful single-evening performance of J.S. Bach’s complete Sonatas and Partitas. In winter/spring 2016 the intrepid FLUX Quartet presents the long-awaited Boston premiere of Morton Feldman’s epic uninterrupted six-hour String Quartet No. 2; and electroacoustic songstress Pamela Z explodes our idea of vocal virtuosity. MIT Sounding – an annual series – is presented by the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST), with support from the School of Humanities, Arts & Social Sciences (SHASS) and the Music & Theater Arts program (MTA). The concert by Johnny Gandelsman is the first annual Terry and Rick Stone Concert. A full schedule and information about the musicians is below.