Interpersonal Approach in Opinion Texts in British and Czech Media Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedy Benefit Programme

MarkT_24pp_Programme:Layout 1 17/09/2007 13:40 Page 1 A seriously funny attempt to get the Serious Fraud Office in the dock! MarkT_24pp_Programme:Layout 1 17/09/2007 13:40 Page 2 Massive thanks to Mark Thomas and all, the performers whove given their time, and jokes tonight , to everyone whos ,made tonight happen everyone who helped with the programme and everyone who . came to see the show PRINTED BY RUSSELL PRESS ON 100% RECYCLED POST-CONSUMER WASTE MarkT_24pp_Programme:Layout 1 17/09/2007 13:40 Page 3 Welcome to tonight’s show! A few words from Mark Thomas Well, I hope you know what you have done, that is all case. And that should have been the end of it. I can say. You and your liberal chums, you think you Normality returns to the realm. The Union Jack flies are so clever coming along to a comedy night at high. Queen walks corgis. Church of England sells Hammersmith, but do you for one minute understand jam at fetes. Children shoot each other on council the consequences of your actions? The money you estates. All are happy in Albion. paid to come and see this show is being used to put the government in the dock! Yes, your money! You did it! You seal cub fondling bleeding heart fop! This so called “benefit” is going to cover the legal costs for taking the Serious Fraud Office to court and you have contributed to it. Where would we be as a country if everyone behaved like you, if everyone went around taking the government to court? Hmm! No one would have fought the Nazis in World War Two, that is where we would be. -

Print Journalism: a Critical Introduction

Print Journalism A critical introduction Print Journalism: A critical introduction provides a unique and thorough insight into the skills required to work within the newspaper, magazine and online journalism industries. Among the many highlighted are: sourcing the news interviewing sub-editing feature writing and editing reviewing designing pages pitching features In addition, separate chapters focus on ethics, reporting courts, covering politics and copyright whilst others look at the history of newspapers and magazines, the structure of the UK print industry (including its financial organisation) and the development of journalism education in the UK, helping to place the coverage of skills within a broader, critical context. All contributors are experienced practising journalists as well as journalism educators from a broad range of UK universities. Contributors: Rod Allen, Peter Cole, Martin Conboy, Chris Frost, Tony Harcup, Tim Holmes, Susan Jones, Richard Keeble, Sarah Niblock, Richard Orange, Iain Stevenson, Neil Thurman, Jane Taylor and Sharon Wheeler. Richard Keeble is Professor of Journalism at Lincoln University and former director of undergraduate studies in the Journalism Department at City University, London. He is the author of Ethics for Journalists (2001) and The Newspapers Handbook, now in its fourth edition (2005). Print Journalism A critical introduction Edited by Richard Keeble First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX9 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Selection and editorial matter © 2005 Richard Keeble; individual chapters © 2005 the contributors All rights reserved. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Israel, You Rascals Mark Steel [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Florida International University Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 6 2014 Israel, You Rascals Mark Steel [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Steel, Mark (2014) "Israel, You Rascals," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 2: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol2/iss2/6 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Israel, You Rascals Abstract Mark Steel started doing stand-up in 1982 in England, around the circuit of bizarre gigs, going on after jugglers and escapologists and people that banged nails into their ear. Then came the Comedy Store and Jongleurs and getting bottled off ta The unneT l, and then a regular slot on Radio 4′s Loose Ends, where he met Joseph Heller, Christopher Lee and Gary Glitter. He did 4 series of ‘The aM rk Steel Solution’, one for Radio 5 and the others on Radio 4, and a radio series about cricket, which provoked a whole page of fury in the Daily Express. He presented three series of a sports programme called ‘Extra Time’ which he was very proud of, especially as it went out on Tuesday nights on Radio 5 to possibly no listeners whatsoever. -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side. -

PSA Awards 2005

POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION AWARDS 2005 29 NOVEMBER 2005 Institute of Directors, 116 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5ED Political Studies Association Awards 2005 Sponsors The Political Studies Association wishes to thank the sponsors of the 2005 Awards: Awards Judges Event Organisers Published in 2005 by Edited by Professor John Benyon Political Studies Association: Political Studies Association Professor Jonathan Tonge Professor Neil Collins Jack Arthurs Department of Politics Dr Catherine McGlynn Dr Catherine Fieschi Professor John Benyon University of Newcastle Professor John Benyon Professor Charlie Jeffery Dr Justin Fisher Newcastle upon Tyne Jack Arthurs Professor Wyn Grant Professor Ivor Gaber NE1 7RU Professor Joni Lovenduski Professor Jonathan Tonge Designed by Professor Lord Parekh Tel: 0191 222 8021 www.infinitedesign.com Professor William Paterson Neil Stewart Associates: Fax: 0191 222 3499 Peter Riddell Eileen Ashbrook e-mail: [email protected] Printed by Neil Stewart Yvonne Le Roux Potts Printers Liz Parkin www.psa.ac.uk Miriam Sigler Marjorie Thompson Copyright © Political Studies Association. All rights reserved Registered Charity no. 1071825 Company limited by guarantee in England and Wales no. 3628986 A W ARDS • 2004 Welcome I am delighted to welcome you to the Political Studies Association 2005 Awards. This event offers a rare opportunity to celebrate the work of academics, politicians and journalists. The health of our democracy requires that persons of high calibre enter public life. Today we celebrate the contributions made by several elected parliamentarians of distinction. Equally, governments rely upon objective and analytical research offered by academics. Today’s event recognizes the substantial contributions made by several intellectuals who have devoted their careers to the conduct of independent and impartial study. -

Download (2260Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4527 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Liza Filby University of Warwick University ID Number: 0558769 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. ……………………………………………… Date………… 2 Abstract The core theme of this thesis explores the evolving position of religion in the British public realm in the 1980s. Recent scholarship on modern religious history has sought to relocate Britain‟s „secularization moment‟ from the industrialization of the nineteenth century to the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. My thesis seeks to add to this debate by examining the way in which the established Church and Christian doctrine continued to play a central role in the politics of the 1980s. More specifically it analyses the conflict between the Conservative party and the once labelled „Tory party at Prayer‟, the Church of England. Both Church and state during this period were at loggerheads, projecting contrasting visions of the Christian underpinnings of the nation‟s political values. The first part of this thesis addresses the established Church. -

Digital Journalism Studies the Key Concepts

Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-2420> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26994/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily (2019). Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts. Routledge key guides . Routledge. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>The key concepts</TITLE></BOOK- PART-META></BOOK-PART> <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>Actants</TITLE></BOOK-PART- META> <BODY>In a special issue of the journal Digital Journalism, focused on reconceptualizsing key theoretical changes reflecting the development of Digital Journalism Studies, Seth Lewis and Oscar Westlund seek to clarify the role of what they term the “four A’s” – namely the human actors, non-human technological actants, audiences and the involvement of all three groups in the activities of news production (Lewis and Westlund, 2014). Like Primo and Zago, Lewis and Westlund argue that innovations in computational software require scholars of digital journalism to interrogate not simply who but what is involved in news production and to establish how non-human actants are disrupting established journalism practices (Primo and Zago, 2015: 38). The examples of technological actants -

Evolution of Political Manifestos with a Study of Proposals to Reform the House of Lords in the 20Th Century

Evolution of Political Manifestos with a study of proposals to Reform the House of Lords in the th 20 Century. by Peter KANGIS Ref. 1840593 Submitted to Kingston University in part fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science by Research. 16 July 2019. 1 Abstract This is a study of how electoral Manifestos have evolved in the 20th century, with a special case study of how Manifesto undertakings in one policy area, that of Reform of the House of Lords, have been delivered by a party when in government. An examination of the Manifestos issued by the Labour, Conservative and Liberal parties for the 27 elections between 1900 and 2001 shows a substantial increase in size on various dimensions and a certain convergence between the parties in their approach to presentational characteristics. A statistical analysis of the overall set of data collected could not confirm that the variations observed were not due to chance. Examination of the relationship between pledges in Manifestos and action taken to reform the House of Lords shows that these pledges were neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for reform to take place. Several reforms have been introduced which had not been pledged in electoral Manifestos whilst several pledges put forward have not been followed up. The study is making several modest contributions to the literature and is highlighting a few areas where further research could be undertaken. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………….……………2 Table of contents: 1 Introduction………………………………………………….…………….………….5 -

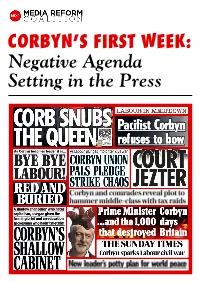

Negative Agenda Setting in the Press Introduction & Reports

CORBYN’S FIRST WEEK: Negative Agenda Setting in the Press Introduction & Reports This new research by the Media Reform Coalition e sitiv shows how the press set out to systematically Po 3% undermine Jeremy Corbyn during his first week as 1 Labour Leader with a barrage of overwhelmingly negative coverage. l a 494 news, r 6 t Our research examined the coverage in 8 national comment and 0 u % e daily newspapers and their Sunday publications editorial N N from 13-19 September 2015. We found that out of e g % pieces 7 a total of 494 news, comment and editorial pieces, a 2 t i v 60% (296 articles) were negative, with only 13% e positive stories (65 articles) and 27% taking a neutral stance (133 articles). News Items One might expect news items, as opposed to on overwhelmingly negative assumptions comment and editorial pieces, to take a more about the new Labour leader who, it should be balanced approach but in fact the opposite is true. remembered, secured some 251,000 votes in the leadership election, in contrast to David Cameron A mere 6% of stories classed as news (19 out of who received just over half this figure in the 292) were positive, versus 61% negative stories Conservative Party’s leadership election. and 32% taking a neutral stance. Any notion of simply ‘reporting the facts’ in straight coverage of This ‘default’ position is particularly significant breaking events appears to have had a restraining given how these stories make up the bulk of the effect on positive stories only, suggesting that coverage during Corbyn’s first week (59% or 292 the default ‘common sense’ position is based articles). -

New Labour's Domestic Policies: Neoliberal, Social Democratic Or a Unique Blend? | Institute for Global Change

New Labour’s Domestic Policies: Neoliberal, Social Democratic or a Unique Blend? GLEN O’HARA Contents Summary 3 The Challenge of Defining eoliberalismN 5 A Government of Its Time 9 Increasing Public Spending 15 Regenerating the Public Sphere 21 Improvement and Advance in Public Services 25 Equality, Inequality and the Individual in Public Services 32 Halting the Drift Towards Increased Income Inequality 39 Re-Establishing Trust? 44 The Language Deficit 50 A Complex Government 53 Not So Neoliberal 58 Downloaded from http://institute.global/news/ new-labours-domestic-policies-neoliberal-social- democratic-or-unique-blend on November 14 2018 SUMMARY SUMMARY It has become commonplace to label the New Labour governments of 1997–2010 a neoliberal project that inflated the property market and financial sector, entrenched inequality and privatised the public sphere. This report examines the record behind, rather than the rhetoric around, these claims. Many popular ideas about Labour in power do not stand up to scrutiny. Overall, New Labour was what it always claimed to be: something genuinely new that fused elements of late-20th- century administrative practice with a socially democratic and deeply Labour emphasis on empowering people, families and communities. Many popular ideas about Labour in power simply do not stand up to such scrutiny. Neither income nor wealth inequality rose; and public services enjoyed a brief golden age of funding and performance, especially important for the most disadvantaged who rely on them the most, and in some of Britain’s poorest areas. Area- based initiatives such as the London Challenge for Schools, and family-focused interventions such as Every Child Matters and Sure Start, opened up public services and opportunities in a way that would have seemed unimaginable in the Thatcherite 1980s. -

Julie Fowlis Mark Steel

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM MAY – AUG 2014 MARK THOMAS JULIE FOWLIS JIM CREGAN & BEN MILLS RICHARD HERRING LYNDA LA PLANTE THEA GILMORE GLENN TILBROOK BARBARA DICKSON MARK STEEL MARTIN ROWSON ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK MAY 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 MAY 2014 WELCOME TO ROPETACKLE From music, comedy, theatre, talks, family events, exhibitions, and much more, we’ve something for everybody to enjoy this summer. As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, nothing comes close to the friendly atmosphere, intimate performance space, and first-class programming that makes Ropetackle one of the South Coast’s most prominent and celebrated arts venues. We believe engagement with the arts is of vital importance to the wellbeing of both individuals and the community, and with such an exciting and eclectic programme ahead of us, we’ll let the events speak for themselves. See you at the bar! THUNKSHOP THURSDAY SUPPERS BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 Our in-house cafe Thunkshop will be serving delicious With support from pre-show suppers from 6pm before most of our Thursday events. Advance booking is recommended but not essential, please contact Sarah on 07957 166092 for further details and to book. Seats are reserved for people dining. Look out for the Thunkshop icon throughout the programme. Programme design by Door 22 Creative www.door22.co.uk @ropetackleart Ropetackle Arts Centre Opera Rock Folk Family Blues Spoken Word Jazz 2 MAY 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 MAY 2014 RICHARD RICHARD DURRANT HERRING CYCLING MUSIC RICHARD HERRING, WE’RE - TOUR & ALBUM ALL GOING TO DIE! ‘a cracking hour of LAUNCH intelligent, thought- With bicycles as lighting stands and provoking satire’ The a stage set carried in panniers, this Edinburgh Evening News will be a truly intriguing concert of beautiful guitar music.